4. Design Practice

4.1. Form Analysis

4.1.1. Living Habits and Visual Preferences of Solitary Bees

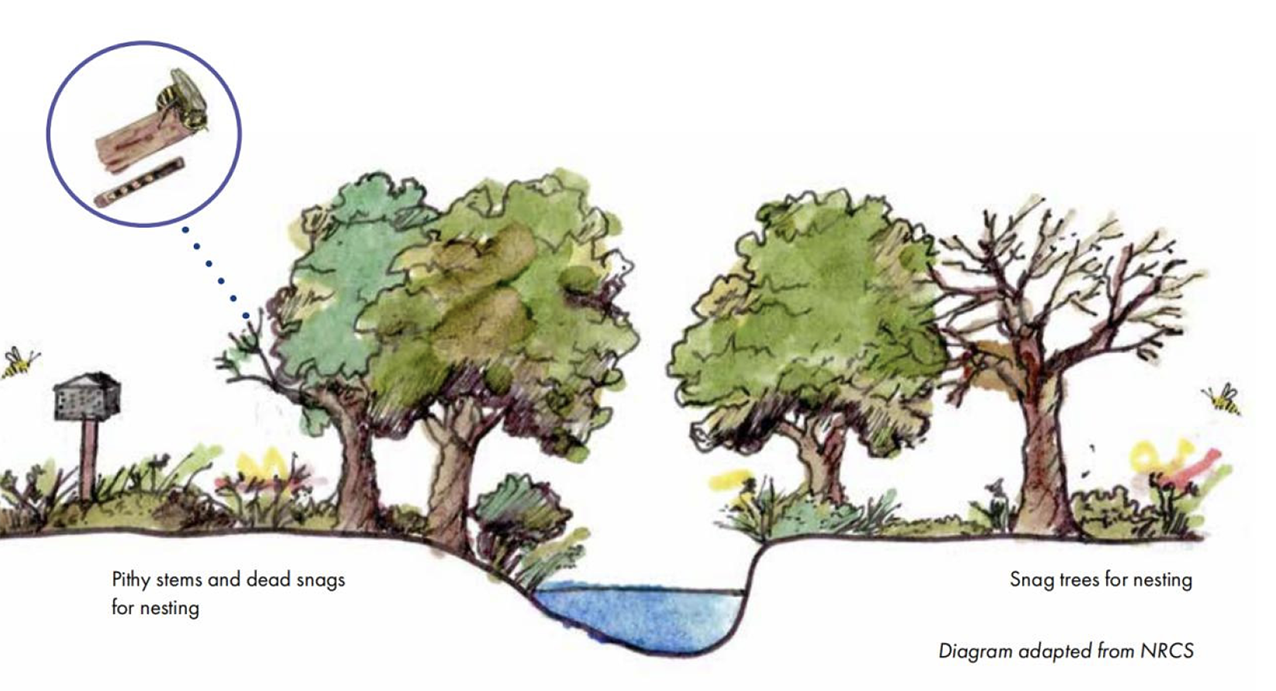

Solitary bees exhibit material preferences when selecting nesting sites. Wooden nest boxes are the most attractive to bees, while hollow plant stems, such as reed stems, also serve as suitable alternatives. Some cases have employed concrete or extruded polystyrene for nest construction.

Different bee species select cavities that match their body width to ensure a snug fit for brood chambers and to prevent parasitism. Therefore, the cavity design must be species-specific, with lengths generally ranging from 150 mm to 200 mm.

Nest boxes should be placed in natural environments, with nectar and pollen sources available within a 100-meter radius and kept stable without relocation. The placement should avoid facing prevailing winds to ensure reproductive success. If positioned near flowers, the height should be above the blooms to avoid blocking the entrance. Nest boxes are best left unpatterned to prevent visual confusion for the bees.

4.1.2. Human Acceptance and Urban Aesthetics

As the nests are placed in urban environments, they must integrate organically with the cityscape, balancing natural simplicity with the structured order of human-made objects.

Although solitary bees pose minimal risk to humans, the general public often harbors fear of bees. Maintaining a safe distance between bees and people is therefore crucial. Nest placement should not be too close to areas frequently used by the public.

4.1.3. Personal Design Expression

This design aims not only to protect solitary bees but also to raise awareness and appreciation of biodiversity and solitary bee species. Consequently, the nest form must possess strong recognizability.

Based on extensive research and prior experience, the design expresses natural simplicity through material choice and conveys a sense of order through form and craftsmanship. Drawing from field research in Jingdezhen and preliminary understanding of 3D ceramic printing, the author recognized that 3D ceramic printing meets the requirement for natural materials while producing industrially expressive, structured forms with distinct layered textures. This method also allows for standardized, batch production, aligning well with the project’s objectives. Therefore, in-depth exploration of 3D ceramic printing was conducted.

4.1.4. Specificity of Material and Fabrication

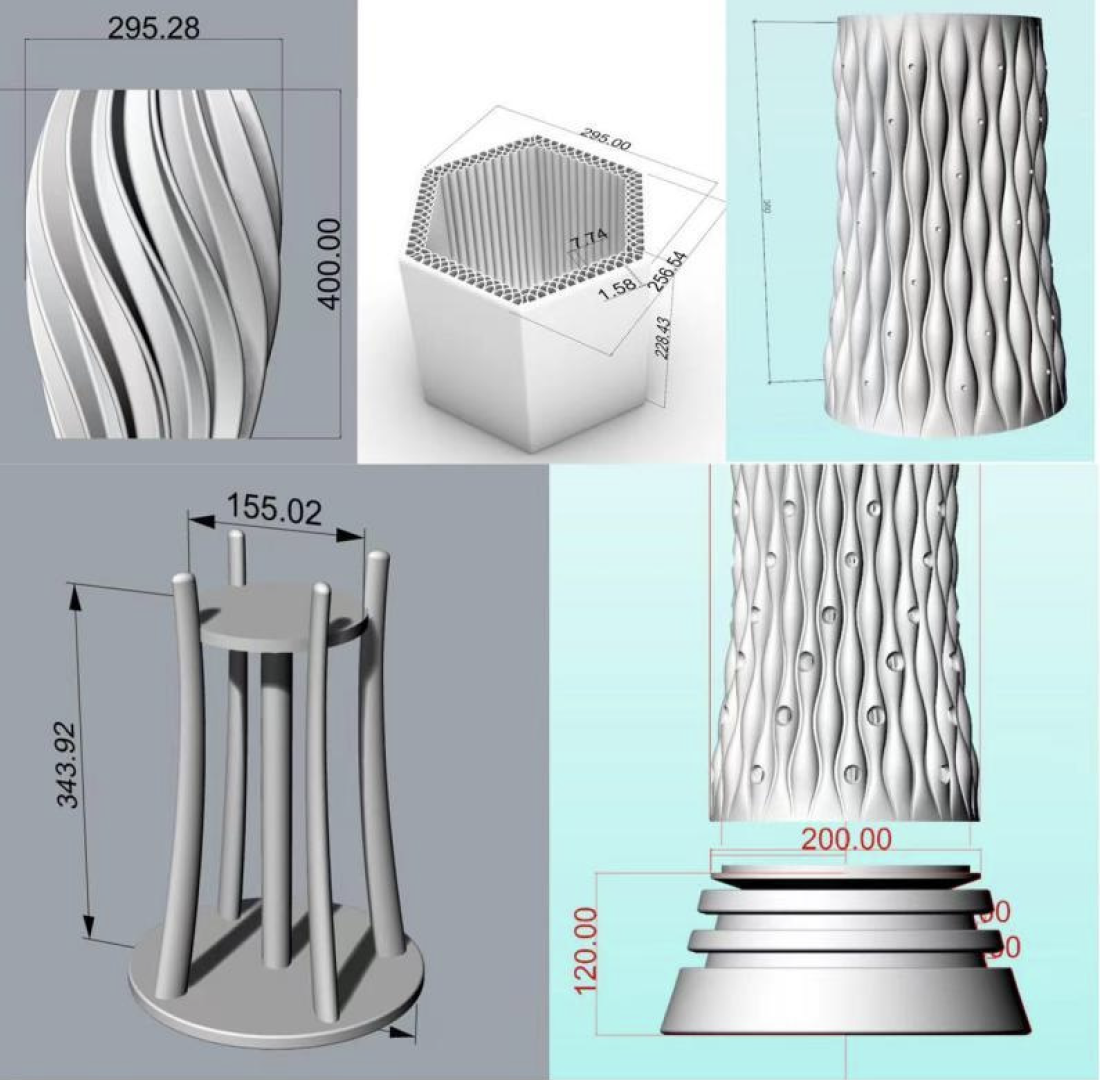

3D ceramic printing builds objects by continuously extruding clay coils through a machine, requiring uninterrupted material flow. As a result, product forms are typically cylindrical, with external form variations achieved through techniques such as parametric design.

4.2. Exploration of 3D Ceramic Printing Processes and Materials

4.2.1. Research and Analysis of 3D Ceramic Printing Technology

3D ceramic printing technology has been widely applied and studied in the fields of ceramic art and medical applications, but its use in industrial product design remains relatively limited. The decision to adopt this technology in the present study is based on three main considerations. First, 3D printing enables industrialized production and compared with traditional hand-thrown ceramic techniques, offers advantages in scalability, standardization, and production efficiency, making it suitable for this design project. Second, ceramic clay is a natural material that is appropriate for outdoor use and is relatively compatible with solitary bees and plants, as it contains no harmful chemical components and can be recycled, thereby supporting ecological sustainability. Third, the use of 3D printing technology allows for future exploration of additional sustainable materials within this project, such as ecological ceramics and hybrid sustainable materials.

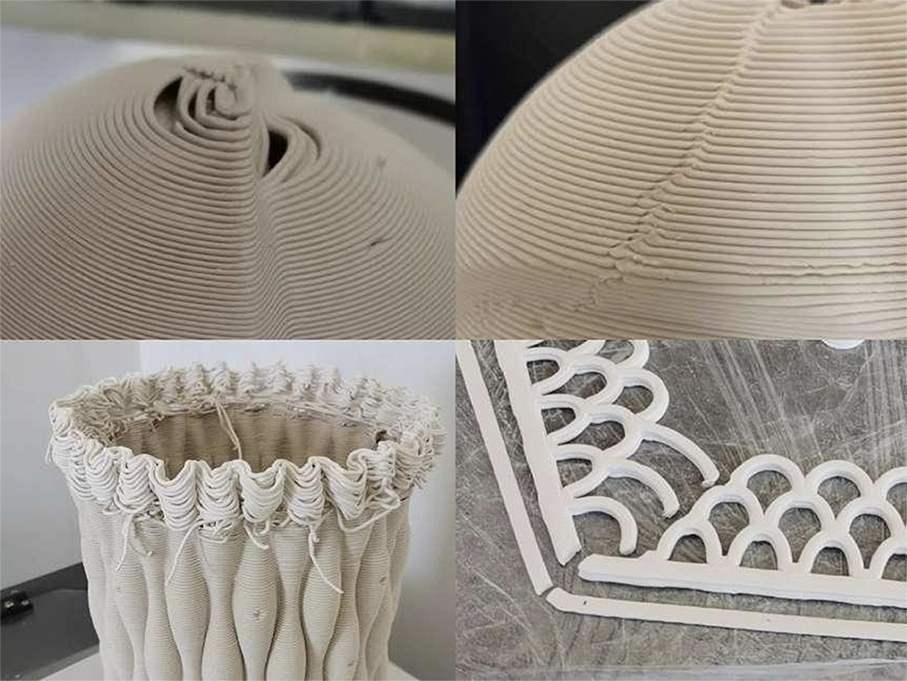

At present, 3D ceramic printing technology in China is still underdeveloped. Limitations in material performance and deformation of ceramic components remain key challenges that urgently need to be addressed in 3D ceramic forming processes [17]. In this study, white porcelain clay was selected as the primary material, which, after firing, produces a natural matte texture and a relatively pure base color. Due to the inherent properties of ceramic clay, the forming process is constrained, requiring repeated experimentation with the curvature and inclination of the beehive surfaces in order to achieve optimal results.

4.2.2. Process Exploration of 3D Ceramic Printing

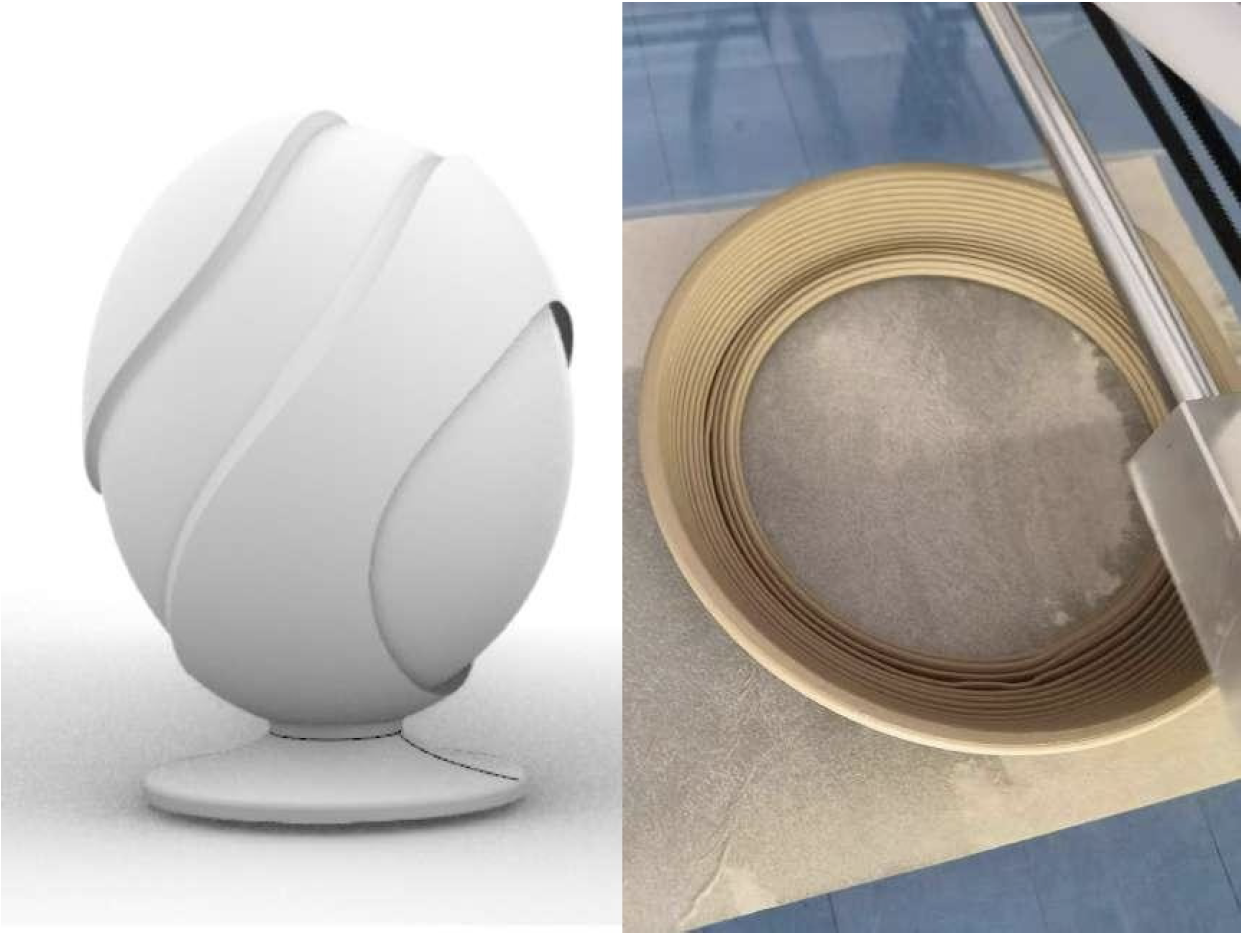

3D ceramic printing technology has been applied primarily to the production of vases and other craft objects. In this project, however, the author sought to employ this technique to fabricate products of relatively large scale, which posed substantial challenges in terms of forming stability. As a result, extensive exploration and experimentation were conducted with both the fabrication process and material performance. At the initial design stage, three different beehive forms were proposed—spherical, cylindrical, and planar. Nevertheless, as the technical investigation progressed, most of these forms proved problematic under the constraints of the printing process.

As shown in Figure 16, the spherical form collapsed during the printing process due to the insufficient load-bearing capacity of the extruded clay coils and excessive weight in the upper section, which caused compressive deformation. The author subsequently elongated the spherical form to reduce the outward inclination angle and improve structural support. However, this adjustment was limited by the maximum height of the printing equipment, preventing the form from reaching the required dimensions. An alternative approach involving segmented printing and subsequent assembly was also tested, but this method resulted in visible manual traces at the joints, introduced excessive procedural complexity, and posed a risk of fracture during firing. Consequently, the spherical form was ultimately abandoned.

3.5. Design Definition

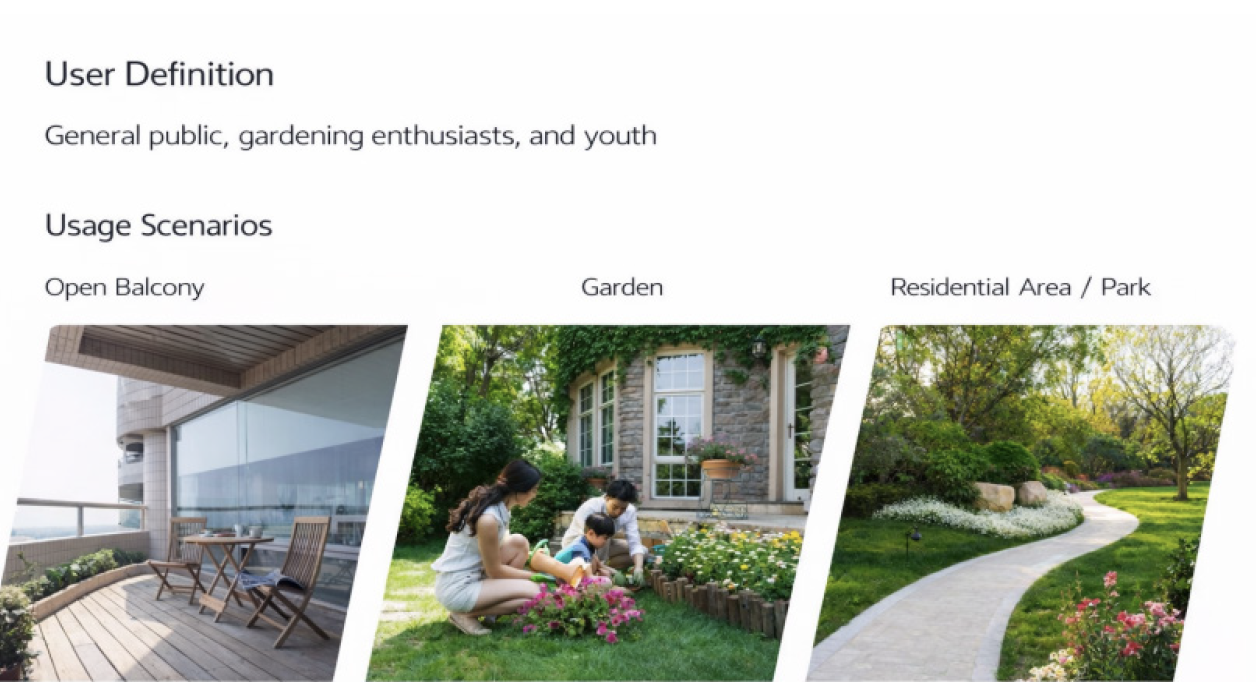

Based on field research and analysis, the design comprises a series of bee nest products in three categories: a standalone bee nest, a bee nest integrated with public facilities, and a bee nest designed for individual users as a horticultural product.

Intended use scenarios include parks, courtyards, and open balconies (Figure 15). Target users are the general public and gardening enthusiasts. Through these products, users can experience both gardening and beekeeping. Public facility-integrated nests increase urban bee populations, enhance urban biodiversity, and raise public awareness and engagement in biodiversity conservation.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Nan Jiang, "Urban Conservation and Design for Solitary Bees: a Case Study of Beijing Olympic Forest Park." JDSSI 3, no.4 (2025): 27-56.

AMA Style

Jiang N. Urban Conservation and Design for Solitary Bees: a Case Study of Beijing Olympic Forest Park. JDSSI. 2025; 3(4): 27-56.

4.4.2. Model Assembly Process

After 3D ceramic printing, the base size was adjusted according to the firing shrinkage. The base was fabricated using 3D plastic printing, followed by sanding and painting. Finally, the components were assembled, and LED strips were installed in the bee lamp (Figure 25).

As shown on the left side of Figure 14, the third design direction involved small solitary bee nest modules adaptable to various public facilities. However, the author considered these modules to be too small in scale and more oriented toward landscape design.

The right side of Figure 14 presents the final design, which integrates bee nests with horticultural elements and public facilities. A series of solitary bee nest products was developed to unify individual, community, and urban environments. This approach is more effective in raising public awareness of biodiversity and solitary bees, ensures the connectivity of bee habitats, and provides a richer and more three-dimensional design language.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- 1. Research Methods and Current State of Research

- 2. Research on Solitary Bees

- 3. Design Research

- 4. Design Practice

- Conclusion and Outlook

- Funding

- Acknowledgements

- Conflicts of Interest

- About the Author(s)

- References

Urban Conservation and Design for Solitary Bees: a Case Study of Beijing Olympic Forest Park

References

1. Wilson, Edward O. “The Biological Diversity Crisis.” Bioscience 35, no. 11 (1985): 700–706. [CrossRef]

2. Frisvold, G.B., and P.T. Condon. “The Convention on Biological Diversity and Agriculture: Implications and Unresolved Debates.” World Development 26, no. 4 (1998): 551–570. [CrossRef]

3. Xinhua News Agency. “Opinions on Further Strengthening Biodiversity Protection.” Xinhua News, October 19, 2021. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2021-10/19/content_5643674.htm. [in Chinese]

4. Jiang, Zhigang, Keping Ma, and Xingguo Han. Conservation Biology. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Science and Technology Press, 1997. [in Chinese]

5. Xie, Gaodi, Lin Zhen, Chunxia Lu, Shuyan Cao, and Yu Xiao. “Provision, Consumption, and Valorization of Ecosystem Services.” Resources Science, no. 1 (2008): 93–99. [in Chinese]

6. Sadeghian, M. M., and Z. Vardanyan. “The Benefits of Urban Parks: A Review of Urban Research.” Journal of Novel Applied Sciences 2, no. 8 (2013): 231–237.

7. Pimm, S. L., C. N. Jenkins, R. Abell, et al. “The Biodiversity of Species and Their Rates of Extinction, Distribution, and Protection.” Science 344 (2014): 1246752. [CrossRef]

8. Dirzo, Rodolfo, and Peter H. Raven. “Global State of Biodiversity and Loss.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 28 (2003): 137–167. [CrossRef]

9. Farinha-Marques, P., João M. Lameiras, C. Fernandes, S. Silva, and F. Guilherme. “Urban Biodiversity: A Review of Current Concepts and Contributions to Multidisciplinary Approaches, Innovation.” The European Journal of Social Science Research 24, no. 3 (2011): 247–271. [CrossRef]

10. Zattara, Eduardo E., and Marcelo A. Aizen. “Worldwide Occurrence Records Suggest a Global Decline in Bee Species Richness.” One Earth 4, no. 1 (2021): 114–123. [CrossRef]

11. Andreucci, M. B., A. Loder, M. Brown, and J. Brajković. “Exploring Challenges and Opportunities of Biophilic Urban Design: Evidence from Research and Experimentation.” Sustainability 13, no. 8 (2021): 4323. [CrossRef]

12. Zhong, Weijie, Torsten Schröder, and Juliette Bekkering. “Biophilic Design in Architecture and Its Contributions to Health, Well-being, and Sustainability: A Critical Review.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 11, no. 1 (2022): 114–141. [CrossRef]

13. Apfelbeck, B., C. Jakoby, M. Hanusch, E. B. Steffani, T. E. Hauck, and W. W. Weisser. “A Conceptual Framework for Choosing Target Species for Wildlife-Inclusive Urban Design.” Sustainability 11, no. 24 (2019): 6972. [CrossRef]

14. Pellkofer, S. D. The Effects of Local and Landscape-Level Characteristics on the Abundance and Diversity of Solitary-Nesting Hymenoptera in Urban Family Gardens. PhD diss., University of Zurich, 2011.

15. Jin, Xiaofang, Fuliu Hao, Zijun Xu, and Haiyan Zhang. “Preliminary Exploration of Bee Brick Houses for Urban Solitary Bee Biodiversity Conservation.” Modern Horticulture (2019), no. 18: 12–14. [in Chinese]

16. Zhang, Lang. “Strategies and Approaches for Enhancing Urban Biodiversity Levels.” Gardens 40, no. 2 (2023): 2–3. [in Chinese]

17. Wang, Cao, Yuying Huang, Yang Liu, and Chang’an Tian. “Research Progress on Ceramic 3D Printing Technology.” Guangdong Chemical Industry 49, no. 22 (2022): 82–84. [in Chinese]

The bee lamp shown in Figure 17 is one of the final design solutions, and the figure broadly illustrates the development process of this form. Initially, the surface texture consisted of a simple arrangement of depressions. The author then optimized it into a pattern of curved protrusions and recesses, enhancing the rhythm and richness of the form, while creating a parametric shape that reinforces the sense of order in the artifact. Finally, the form was tapered at both ends to achieve a more natural transition. During the printing process, collapse occurred due to issues with the slicing path, but after adjustments, the final model was successfully printed.

Figure 18 presents a brief overview of some failed attempts; in reality, the number and complexity of failures during the exploration process far exceeded what is shown. These included issues such as the supporting capacity of clay, the connection between clay strips, the form’s sealing integrity, the selection of clay strip thickness, and certain forms that could not be realized using this technique, among others.

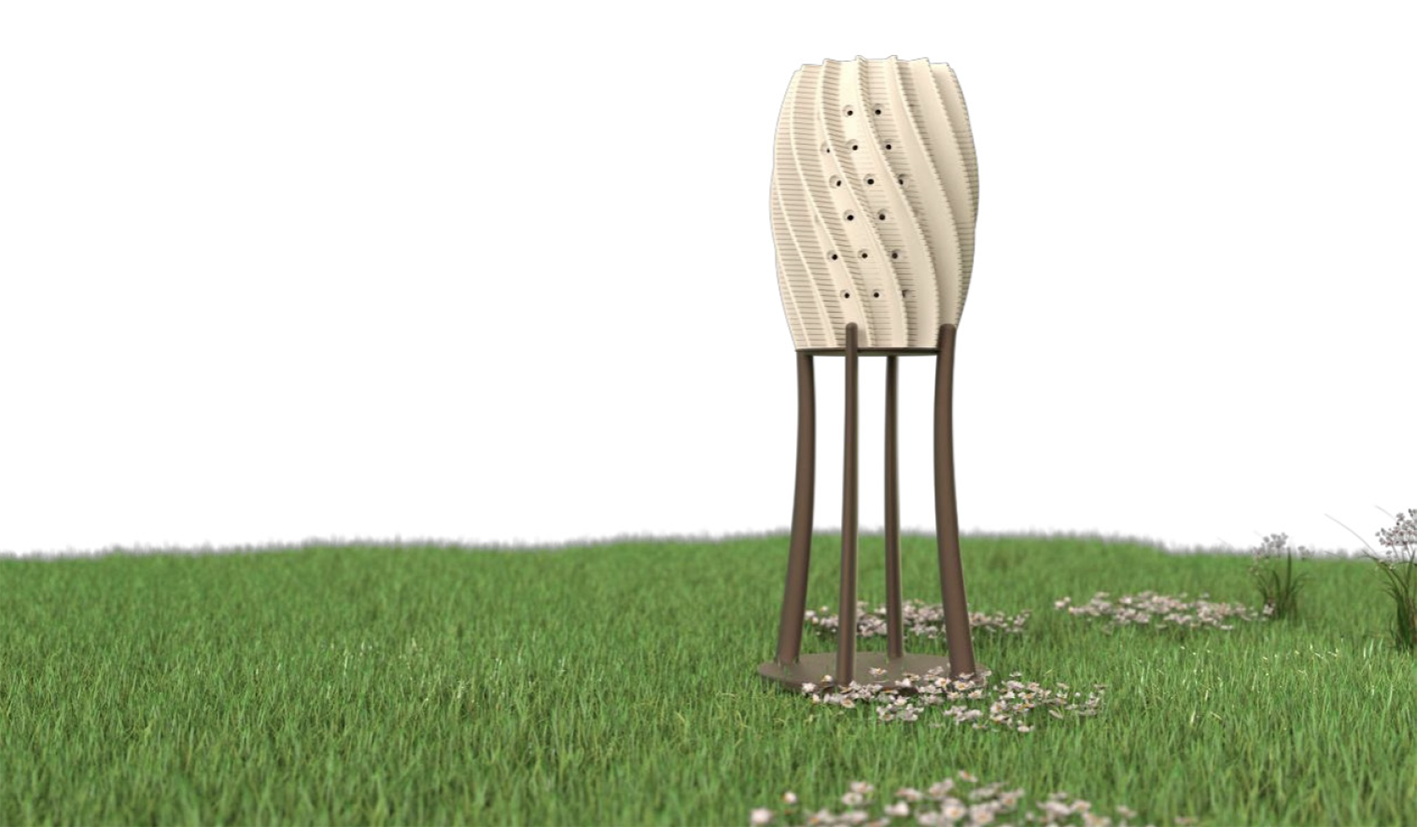

4.3. Final Product Form, Structure, and Dimensions

The design process of this project was highly iterative and complex. During the initial phase of divergent concept development and subsequent adaptation to production techniques, numerous variations and iterations of form and structure were explored. The final outcome achieved a relatively unified integration of form, function, and material technique (Figure 19).

The series consists of three works primarily divided into two structural types. The first type is a hollow, capped cylindrical form, with perforations on the exterior surface into which natural wheat straw tubes are inserted to simulate the natural environment. This design aligns with the natural preferences of solitary bees, providing suitable reproductive nests. The second type is a bottom-sealed basin form that does not require additional materials; the vertical tubular structure is formed directly through printing, making it more compatible with the fabrication process. However, this approach has the drawback of water accumulation and is therefore more suitable for semi-open balconies or outdoor spaces with a canopy (Figures 20a, 20b, 21, and 22).

Because this design employs 3D ceramic printing, the products require firing, which causes shrinkage. The shrinkage rate cannot be precisely determined, as it is affected by the clay material, kiln temperature, and the placement of the product during firing. The clay material currently used has an approximate shrinkage rate of 17%. The base dimensions also need to be slightly adjusted according to the post-firing size. The final dimensions of the fired models, from largest to smallest, are approximately 663 mm × 155 mm × 155 mm, 440 mm × 200 mm × 200 mm, and 244 mm × 212 mm × 190 mm (Figure 23).

4.4. Model Fabrication

4.4.1. 3D Ceramic Printing Technology

After finalizing the forms through continuous adjustments, the author created 3D models in Rhino and sliced them to generate printing paths. The printed models were left to dry for 2–3 days, after which holes were manually carved while still partially moist, before firing in a kiln. The complete fabrication process took approximately 6–7 days per product (Figure 24).

4.5. Physical Model

As part of the design’s aesthetic appeal derives from its material and fabrication, renderings alone cannot fully convey the product’s visual impact. The prototypes were therefore placed in roadside urban green spaces for video and photographic documentation (Figures 26, 27 and 28).

The shoot took place in early June, when solitary bees were largely inactive; nevertheless, the author was fortunate to capture footage of a bee circling the product for an entire lap (Figures 29a and 29b).

Funding

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest related to this research.

About the Author(s):

▪ Nan Jiang holds a master’s degree in design for Sustainability from the Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) and a bachelor’s degree in industrial design from Tsinghua University. Her practice focuses on sustainability, urban ecology, gender issues, and education, exploring how design can address social and environmental challenges through inclusive and research-driven approaches. She works across product, system, and public space design, integrating ecological knowledge with social narratives. Now she is an assistant researcher at the Center for Cultural Heritage Inheritance and Innovation, Hubei University.

The Research Center of Inheritance and Innovation of Cultural Heritage, Hubei University, Wuhan, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JDSSI. 2025, 3(4), 27-56; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jdssi2025.1228a42

Received: September 18, 2025 | Accepted: November 25, 2025 | Published: December 28, 2025

Nan Jiang *

by

Abstract: With the continuous advancement of urbanization, urban biodiversity has been increasingly threatened. Solitary bees are important pollinators that play a significant and unique role within urban ecosystems; however, their populations have declined sharply in recent years, with many species approaching extinction. The design to be discussed aims to protect urban biodiversity by creating a series of bee nests for solitary bees within the city.

The nests are integrated with urban public facilities and horticultural products, utilizing 3D ceramic printing technology to create habitats that align with the natural behaviors of solitary bees and ensure strong ecological connectivity. These nests are designed to blend organically into the urban environment and human activities, with the goal of restoring solitary bee populations in cities.

This study analyzes the habitats required by solitary bees from three perspectives: behavioral habits, living spaces, and nest structures. Through literature review and case studies, it examines the critical decline in solitary bee populations, identifies design requirements for bee nests, and explores methods for their seamless integration into urban environments. The 3D ceramic printing technology employed in this design features a distinctive layered texture and unique shaping properties. Extensive research and experimentation were conducted on materials and processes to unify the design’s structure, form, and function.

Introduction

The term biodiversity was introduced in 1986 by Harvard scholar E. O. Wilson [1]. In 1992, the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity defined biodiversity as the variability among all living organisms on Earth, including terrestrial, marine, and other ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part, encompassing diversity within species, between species, and among ecosystems [2]. As a member of the Earth community, human survival and development are profoundly dependent on ecosystems, which provide “a wide range of essential goods for production and daily life, a healthy and secure ecological environment, and distinctive landscape and cultural values” [3]. During the same period, the Chinese scholar Zhigang Jiang further explained biodiversity as the ecological complex formed by organisms and their environments, together with the various ecological processes associated with them, including animals, plants, microorganisms, their genetic resources, and the complex ecosystems formed through their interactions with living environments [4]. Ecosystem services refer to the natural benefits generated and sustained by ecosystems and ecological processes on which human survival depends, such as air, freshwater, food, and recreation [5].

Urban biodiversity is the result of environmental filtering in cities and human selection. Unlike traditional biodiversity research, urban biodiversity requires a focused coordination between development and conservation, where protection serves as the foundation and utilization is both the key and the ultimate goal [6].

Due to human activities and urbanization, habitats have been severely compressed, and many species now face the risk of extinction. Although species extinction occurs naturally, human influence has accelerated species loss to a rate approximately 1,000 times faster than under natural conditions [7], representing the “only truly irreversible global environmental change” facing the Earth [8]. At the same time, urbanization also provides new opportunities for biodiversity conservation [9].

Bees are important pollinating insects. While social honeybees are the most familiar, solitary bees constitute a significant branch of the bee family, with approximately 20,000 to 30,000 species, accounting for 90% of all bee species. Their pollination efficiency is 120–200 times that of honeybees, making them indispensable for ecological conservation. In urban ecosystems, solitary bees are responsible for pollinating roughly one-third of crops and flowering plants, forming a critical component in maintaining ecological stability. However, widespread pesticide use, loss of food resources, and habitat destruction have caused a dramatic decline in solitary bee populations, with many species now approaching extinction. Research also shows that the number of honeybee species collected between 2006 and 2015 declined by approximately 25% compared to the 1990s [10].

Research and design focused on urban solitary bee conservation can restore their populations, protect urban biodiversity, enhance the quality of urban life, and increase both aesthetic and economic value. Biophilic design, implemented at the scales of buildings, communities, and cities, can connect daily human life with biodiversity, simultaneously contributing to environmental and public health improvements [11]. Its framework includes design strategies involving animal and plant elements, such as integrating vegetation into buildings and creating animal-friendly habitats [12].

Existing research on urban solitary bees is primarily grounded in biological and ecological theory. For example, Wildlife Inclusive Urban Design emphasizes balancing the needs of humans and wildlife to create new habitats within urbanized areas [13]. However, studies translating these theoretical insights into practical design products remain limited.

From a product perspective, solitary bee conservation design is still in its early stages. Most solitary bee nest designs consist of simple tubular bundles, which are visually unappealing, primarily intended for biological research, functionally limited, and not organically integrated into the urban environment. This design aims to combine solitary bee conservation products with urban functionality, allowing solitary bees to find suitable locations and spaces within human-dominated urban areas.

2.4. Case Studies on Bee Conservation Design

(A) Bee Brick

The Bee Brick, designed by the Green&Blue studio, is made from 75% recycled concrete (Figure 4). The front face contains multiple holes of varying sizes where bees can lay eggs, which are then sealed with mud or other materials, fully simulating the natural environment of a bee nest. The design allows flexible placement in various urban locations while maintaining a natural and aesthetically appealing appearance.

3. Design Research

3.1. Preliminary Design Analysis

Given the highly fragmented nature of urban landscapes, urban biodiversity conservation cannot be confined to traditional biological concepts; research should be conducted flexibly across multiple spaces and perspectives [16].

The creation of habitats for urban solitary bees should respect the city’s existing spatial functions and cultural attributes. The bees’ food sources should span from early spring to late autumn, with plants of varying flowering periods cultivated to enhance floral diversity. Planting arrangements should also consider public use, and maintenance standards must be defined, with dedicated personnel responsible for daily upkeep.

Since the primary function of cities is to serve humans, bee nests need to be integrated into the urban environment. Therefore, the author has combined solitary bee nests with public facilities or urban buildings. Urban public facilities effectively meet the shared needs of both bees and humans. In the divergent design phase, the author explored integrating bee nests with various types of public facilities, while also endowing them with product attributes to enable public participation in solitary bee conservation.

3.2. Research and Analysis of Public Facilities

Urban public facilities are numerous and are scattered around city green spaces, streets, and parks. They provide suitable living conditions for solitary bees and help connect their habitats. Therefore, the author explored the possibility of integrating solitary bee nests with public facilities (Figure 9).

Conclusion and Outlook

This project focuses on designing for urban biodiversity, an emerging field in which the translation of theoretical research into design remains limited, and few reference cases exist. As a result, extensive exploration and experimentation in terms of functionality, form, and structure were required, and considerable time was devoted to defining the project and confirming the initial design proposals. Based on the author’s experience and understanding of fabrication processes, once 3D ceramic printing was confirmed as the production technique, the design progressed rapidly. Unlike conventional design workflows that first finalize the concept and then produce prototypes, this project required repeated iterations of form and function in close conjunction with the unique characteristics of the chosen fabrication method. This approach offered new insights into design processes, demonstrating how production techniques can significantly drive innovation and inspire creative solutions.

Due to constraints in research time and resources, there are certain limitations in this study of urban solitary bee conservation. These include a relatively narrow scope of literature review, ongoing technical refinement needed for 3D ceramic printing in both software and hardware, and the absence of long-term field validation due to environmental and temporal limitations. Nevertheless, the author hopes that the exploration and design outcomes presented here can provide valuable reference points for future urban solitary bee conservation efforts and contribute to the broader protection of urban biodiversity.

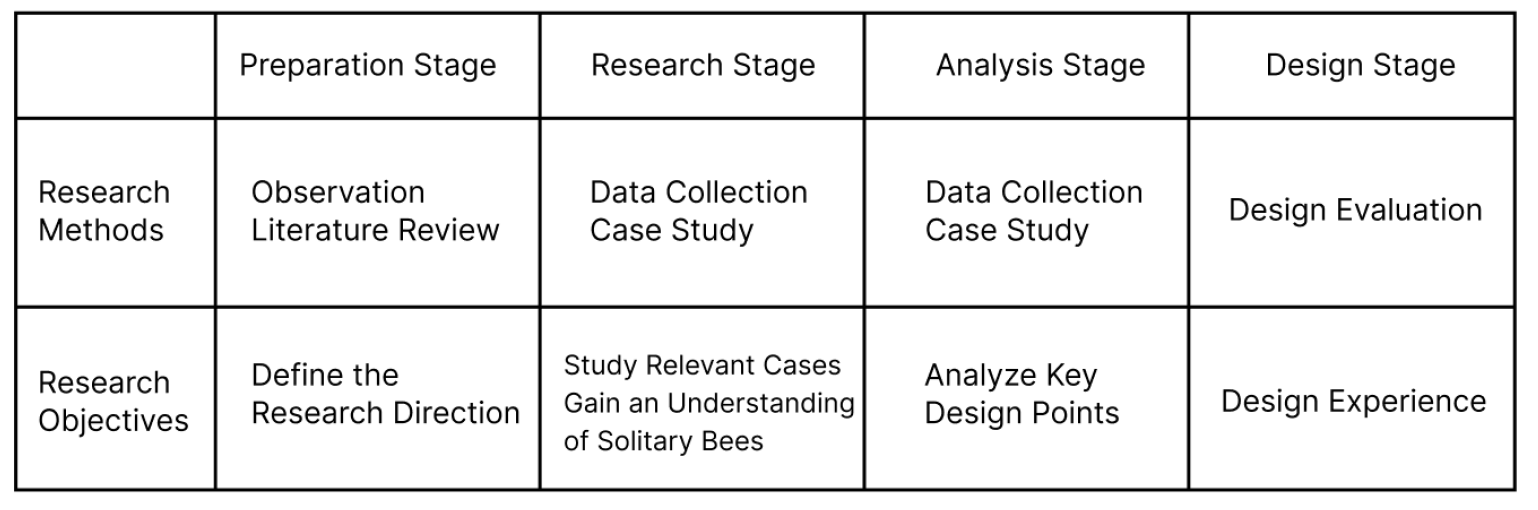

1. Research Methods and Current State of Research

1.1. Research Methods

Different research methods were employed at various stages of this study, as shown in Table 1. As the design target is animals rather than humans, the investigation primarily relied on indirect research approaches.

1.2. Current State of Research

Previous research on solitary bees has a long history, covering diverse and in-depth directions. Substantial studies have been conducted in biology, wildlife conservation, veterinary science, foundational agricultural sciences, and horticulture, yielding abundant experimental and observational data. These studies provide concrete research and conclusions regarding solitary bee nests in urban environments. Nest houses designed for the conservation and study of solitary Hymenoptera have been widely implemented in developed countries such as the Netherlands, Canada, and the United States [14]. In China, research on solitary bees has primarily focused on biological studies or general summaries and popular science, with almost no research on wild solitary bees in urban areas, indicating a notable gap compared with other studies.

During the preliminary research phase of this project, the author systematically reviewed academic literature and expert studies related to the ecological characteristics of solitary bees, urban biodiversity, and the ecological design of public spaces. By analyzing the work of ecologists and environmental design scholars on solitary bee habitat requirements, life cycles, and survival challenges in urban environments, the key requirements of solitary bees for nest structure, materials, and spatial scale were clarified. At the same time, existing research on ecological infrastructure and public environmental education provided important insights for this project, prompting a shift from single-species protection toward a systematic consideration of coexistence between human and non-human species. These references established the theoretical foundation for defining subsequent design directions and developing design strategies.

2. Research on Solitary Bees

2.1. Survey of the Current Status of Solitary Bees

Statistics indicate that more than one-third of the world’s crop yield depends on pollination by solitary bees. Consequently, the decline of solitary bees can have a profound impact on agriculture [15]. A reduction in solitary bee populations leads to decreased plant diversity, reduced numbers of insects and birds, increased frequency of pests and diseases, and disruption of ecological balance and environmental sustainability.

Currently, the global population of solitary bees is declining rapidly, with many species facing the risk of extinction. The primary causes include a drastic reduction in flowering plants, environmental degradation, and the widespread use of pesticides and insecticides, which pose lethal threats to solitary bees. In addition, commercial beekeeping has introduced large numbers of non-native species, placing further pressure on native species.

Public awareness of solitary bees is generally low. Bees are often equated solely with honey-producing social bees, resulting in minimal attention to solitary bees. Furthermore, fear of bees among the general population makes conservation efforts for solitary bees more challenging.

2.2. Behavioral Characteristics and Habitat Research of Solitary Bees

2.2.1. Survey of Urban Solitary Bee Species

Urban solitary bee species are primarily represented by colletidae bees, mason bees, leafcutter bees, and carpenter bees. Northern Chinese cities host a rich diversity of solitary bees, covering multiple provinces. In this study, leafcutter bees were selected as the main research focus. The survey included species of the family Megachilidae distributed across northern Chinese cities. For example, the double-leaf leafcutter bee is mainly found in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Fujian, Jiangxi, Shandong, Sichuan, and Taiwan. In China, leafcutter bees are predominantly distributed in Beijing, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, and Gansu, with northern populations concentrated in Beijing, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Heilongjiang, Shandong, and Shaanxi. The yellow-phosphorus leafcutter bee is mainly found in Beijing, Shanxi, Shandong, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, Qinghai, and Xinjiang.

While most people associate bees with stings and danger, solitary bees differ significantly. They do not need to protect nests or queens, are generally docile, and rarely sting. Therefore, solitary bees pose little threat to humans when living in urban environments.

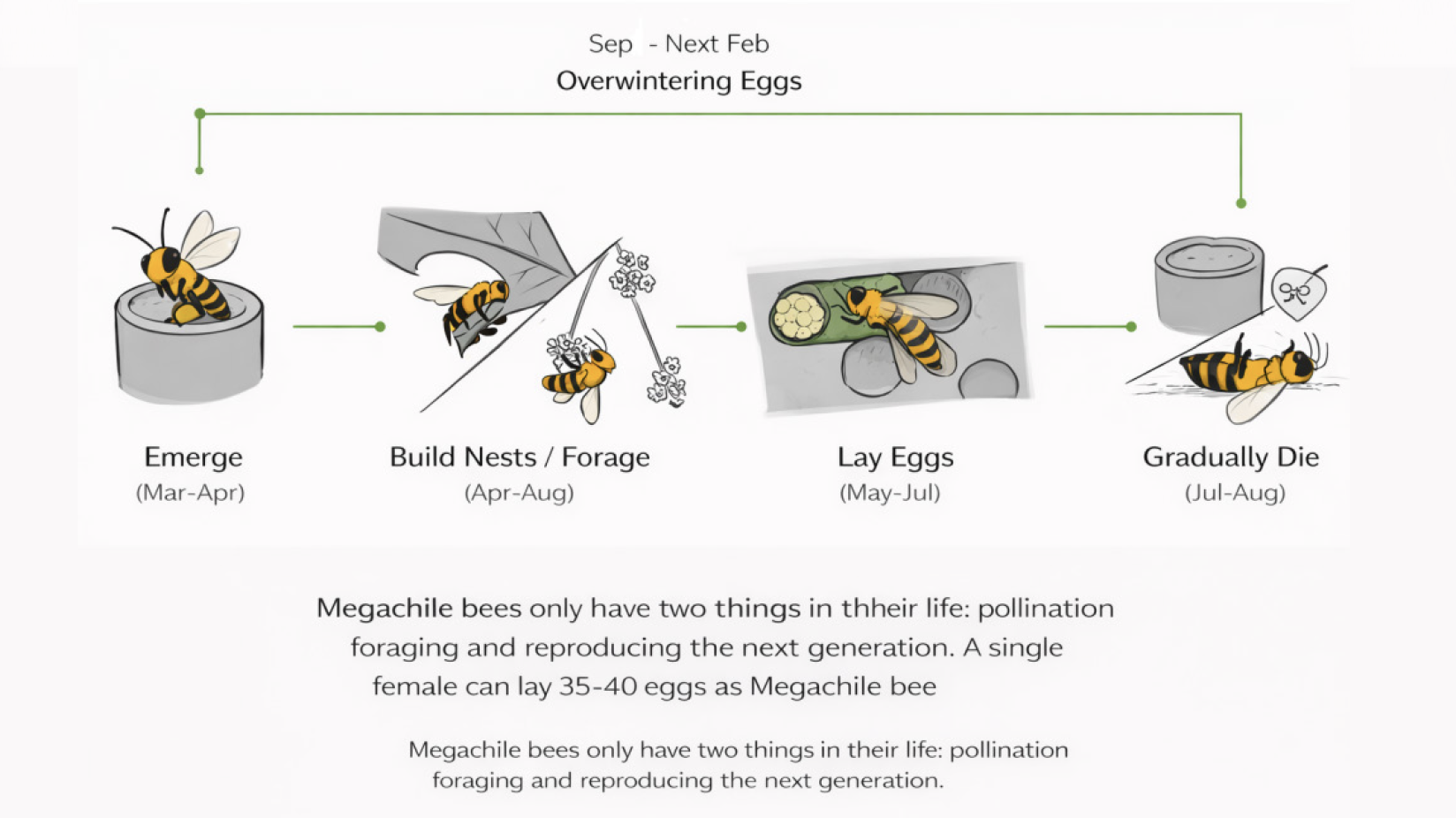

2.2.2. Study of Solitary Bee Behavior

Most solitary bees are univoltine, living only for one year. For instance, leafcutter bees have a lifespan of approximately 60 days, with males living even shorter lives and gradually dying after mating. Throughout their lifespan, solitary bees engage primarily in two key behaviors: foraging for flowers and reproduction.

Taking leafcutter bees as an example, a single female can lay 35–40 eggs. Each spring, eggs that have overwintered in the nest begin to develop and hatch into adults, which then continuously visit flowers to pollinate plants, collecting pollen on their abdomens. After mating, the female leafcutter bee cuts leaves or transports soil to construct nests. Eggs are deposited in appropriately sized cavities in the ground, wood crevices, or plant stems. Each egg is separated by leaves or soil into individual compartments (Figures 1 and 2), with pollen provisioned inside for the developing offspring. Finally, the entrance of each nest is sealed to protect the eggs.

As farmland increasingly transitions to industrialized production, crop monocultures and uniform agricultural management practices pose significant threats to bee survival. Pesticides and other chemical agrochemicals are particularly hazardous. A study conducted by the University of Guelph in Canada found that a commonly used insecticide can impair a bee’s ability to groom its body hairs properly, making it highly susceptible to harmful mite infestations and resulting in death. Orchards often introduce non-native honeybees for pollination, creating intense competition for native bees. In addition, large-scale monoculture plantings in orchards result in concentrated flowering periods, which fail to provide a sustained food source for bees.

In contrast, urban environments often enhance plant diversity for aesthetic purposes. Parks frequently contain a variety of flowering species with staggered bloom periods across spring, summer, and autumn. For example, in Beijing Olympic Forest Park, by 2008, there were more than 100 tree species totaling 530,000 individuals, over 80 shrub species, and more than 100 ground-cover species. This diversity ensures a consistent food supply for solitary bees while avoiding competition from non-native species, allowing them to utilize urban environments more effectively. Therefore, urban areas play an irreplaceable role in the conservation of solitary bees.

2.3. Analysis of the Necessity for Solitary Bee Conservation

Solitary bees play an irreplaceable role in ecosystems and possess unique characteristics. They are a crucial pathway for plant reproduction, yet their populations have continued to decline in recent years, with some species approaching extinction.

From the perspective of biodiversity conservation, no species is inherently superior or inferior; all species hold intrinsic value and collectively contribute to ecological balance. However, in the context of urban biodiversity, the primary function of cities is to serve human needs, which alters the evaluation criteria. In the intricate and densely structured urban environment, meeting the diverse needs of human survival while creating complex ecosystems with numerous elements—systems that are difficult to assess and maintain—is particularly challenging.

Compared with other complex natural habitats, the requirements of solitary bees are relatively simple and manageable. Their primary needs are nesting sites for reproduction, nectar- and pollen-providing plants, and connected habitats. All three can be provided, monitored, and maintained by humans. Solitary bees operate independently within urban spaces without disrupting city functions, while simultaneously pollinating various urban plants, thus supporting urban ecology and enhancing the aesthetic quality of the city.

Through industrial design, it is possible to create small-scale habitats suitable for solitary bees within human-dominated urban landscapes. Such interventions can provide compensation for human impacts and contribute to urban ecological maintenance and biodiversity conservation.

Solitary bees primarily feed on nectar and pollen. They collect nectar from flowers and consume it as a source of energy, while pollen provides essential proteins and other nutrients. Solitary bees pollinate a wide variety of flowering plants, including fruit trees, vegetables, and ornamental species. In addition to nectar and pollen, some leafcutter bees occasionally consume plant sap or other insects.

The foraging range of solitary bees is approximately 62 to 154 meters. The main nectar-collecting season occurs from April to August, with bees typically emerging in spring and remaining active throughout the summer. Therefore, it is important to ensure that a diversity of flowering plants with staggered bloom periods is available within their foraging range.

The Great Barrington Pollinator Action Plan emphasizes that, in addition to pollen and nectar, bees require nesting materials and suitable habitats, with habitat connectivity being critical. Establishing pollinator habitats in urban centers can strengthen ecological linkages across the landscape. Furthermore, an appropriate density and spatial distribution of nests within the city are essential for enhancing both the richness and connectivity of bee populations in human-dominated environments (Figure 3).

(C) Bee Bus Stop

This design is the “Bee Bus Stop” located in Leicester, United Kingdom (Figure 6). The bus stop’s roof is transformed into a green space that connects streets, effectively creating an “ecological corridor.” By attracting and protecting pollinators such as bees and butterflies, the project contributes to the conservation of urban biodiversity.

(B) Bee Home

The modular solitary bee nest developed by SPACE10 provides individual cavities for each bee to store food and shelter their eggs. Most solitary bees naturally inhabit tree holes or underground burrows, and the Bee Home design (Figure 5) takes these natural habits into full consideration by emulating the form of a tree cavity. At the same time, the modular design ensures that each nest is unique, allowing users to experience enjoyment during the assembly process.

(D) Bee Hospital

Set in 2030, this project aims to support bees in increasingly degraded urban environments. It includes devices such as a mite prevention dispenser, a bee monitoring station, and an energy supplement center (Figure 7).

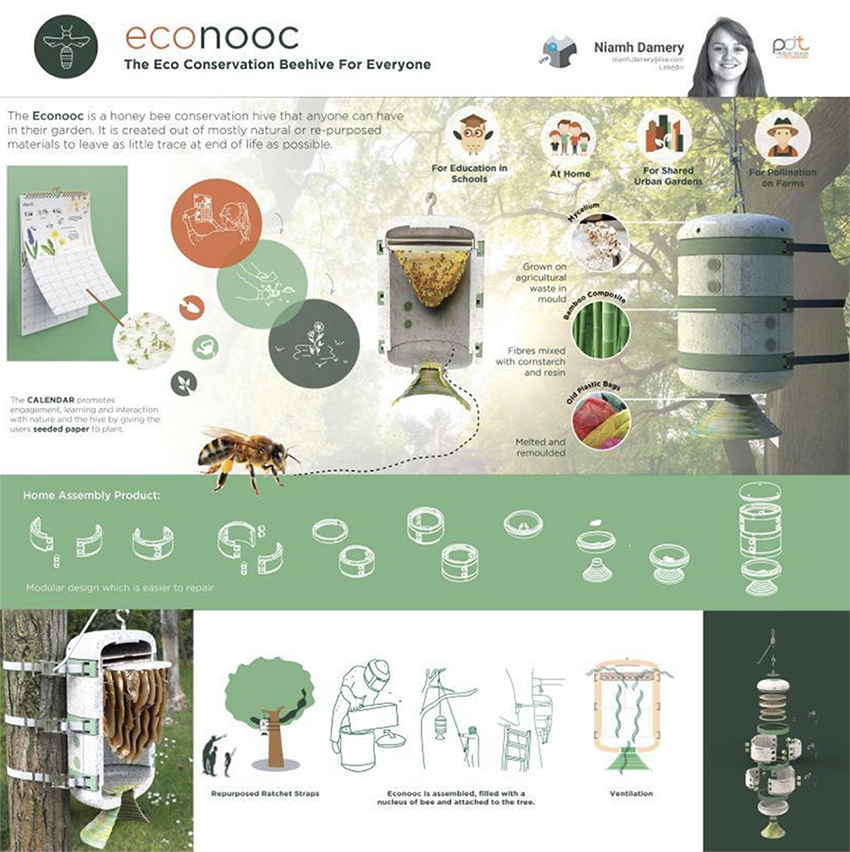

(E) Econooc

This design uses mycelium and other sustainable materials to construct bee nests (Figure 8). It features a plant calendar that guides users to grow seasonal wildflowers in their gardens, supporting their own bees and promoting biodiversity awareness. Although this design targets social bees, it still provides useful references for solitary bee conservation.

In summary, while the number of urban solitary bee conservation designs remains limited, successful examples already exist. Many design competitions, such as the Dezeen Award and James Dyson Award, showcase works focused on bee protection and biodiversity-oriented design. Public awareness of solitary bee conservation is gradually increasing. There remain numerous avenues for in-depth research, and significant potential exists for further integrating design into urban solitary bee conservation.

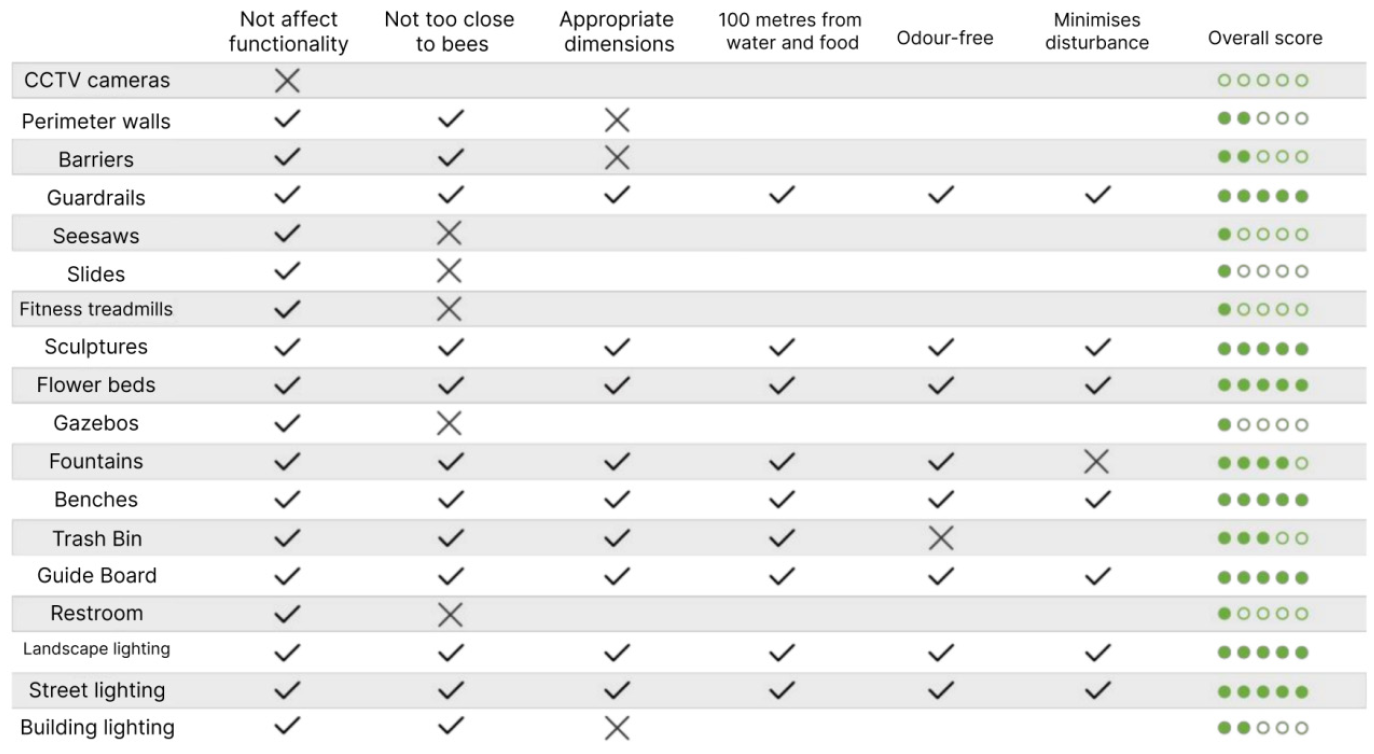

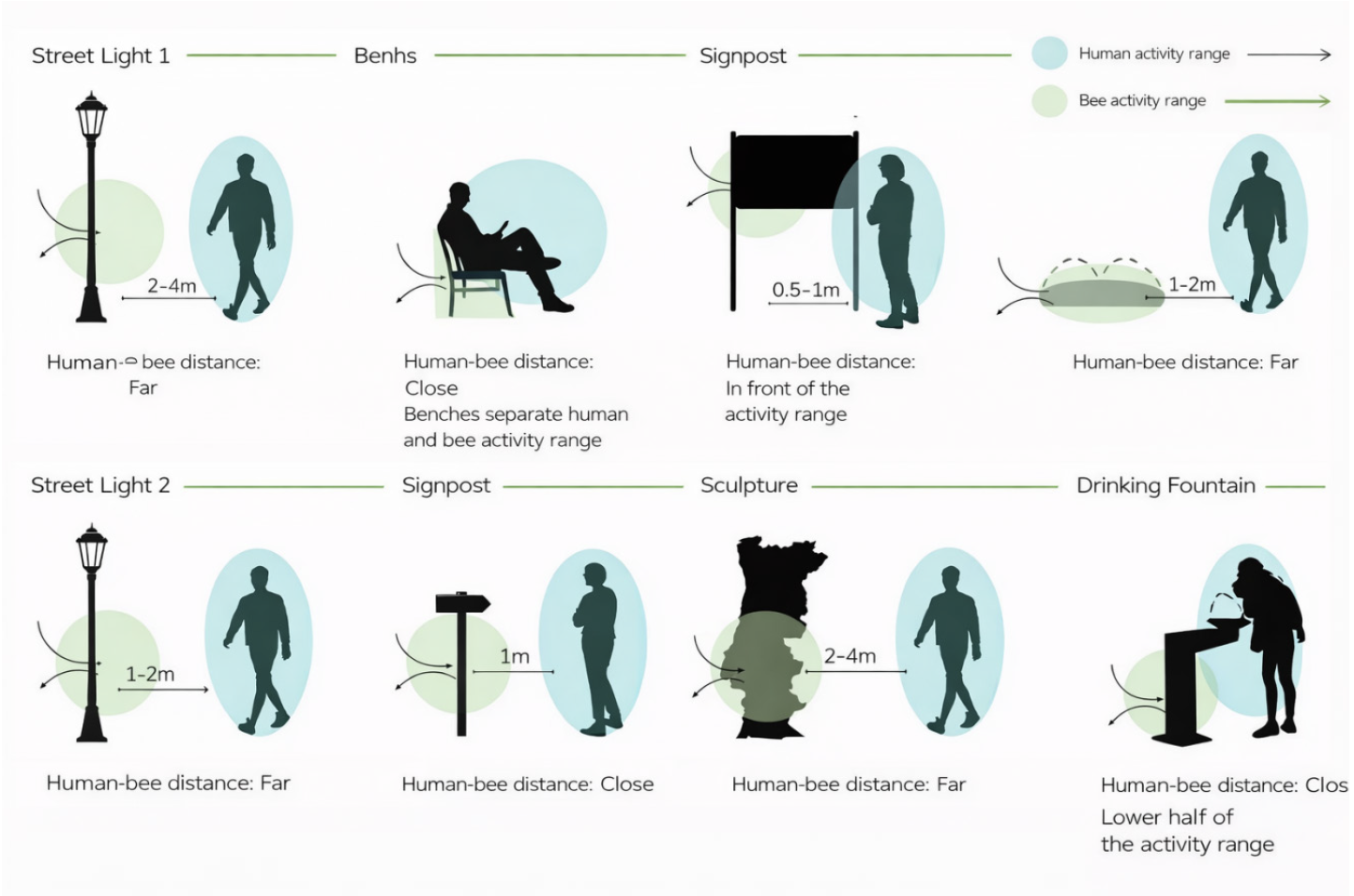

In selecting types of public facilities, the author applied the following criteria: the facility’s primary function must not be affected, the bees should not be overly disturbed, the size and height should be appropriate, the facility should be within 100 meters of water and food sources, and it should not emit odors or otherwise excessively interfere with the bees. Based on these criteria, streetlights, benches, signboards, fountains, traffic signs, sculptures, and drinking stations were selected as the focus for design development.

The author conducted a more detailed analysis of the selected public facilities (Figure 10). Human interaction with public facilities determines both the range of human activity and the distance between people and the facilities. Using diagrams, the study defined the zones of human activity and solitary bee activity, aiming to ensure that the bees’ and humans’ activity ranges do not interfere with each other. This research provides guidance and reference for the subsequent development and refinement of the design proposals.

3.3. Field Analysis: Beijing Olympic Forest Park

To investigate the current state and density of public facilities in urban parks, the author conducted a field survey and analysis at Beijing Olympic Forest Park (Figure 11). Observations revealed that the density of public facilities is very high; in some areas, four types of signboards with different visual languages appeared within three meters, creating significant visual clutter. Integrating bee nests with these public facilities, however, could leverage this density to help connect solitary bee habitats.

The author estimated the foraging range of leafcutter bees based on the map of Beijing Olympic Forest Park. The park’s vegetation can be broadly categorized into dense forested areas, sparse woodland and grasslands, wetlands, and wildflower meadows. Solitary bees are best suited to survive in the wildflower meadow areas, which can accommodate approximately 70 foraging ranges. Each foraging range requires one to two bee nest points, and the number of potential public facility locations is more than sufficient to support the creation of solitary bee habitats (Figure 12).

3.4. Conceptual Design Development and Analysis

Following the analysis of urban spaces and public facilities, the author conducted a divergent exploration and analysis of design proposals.

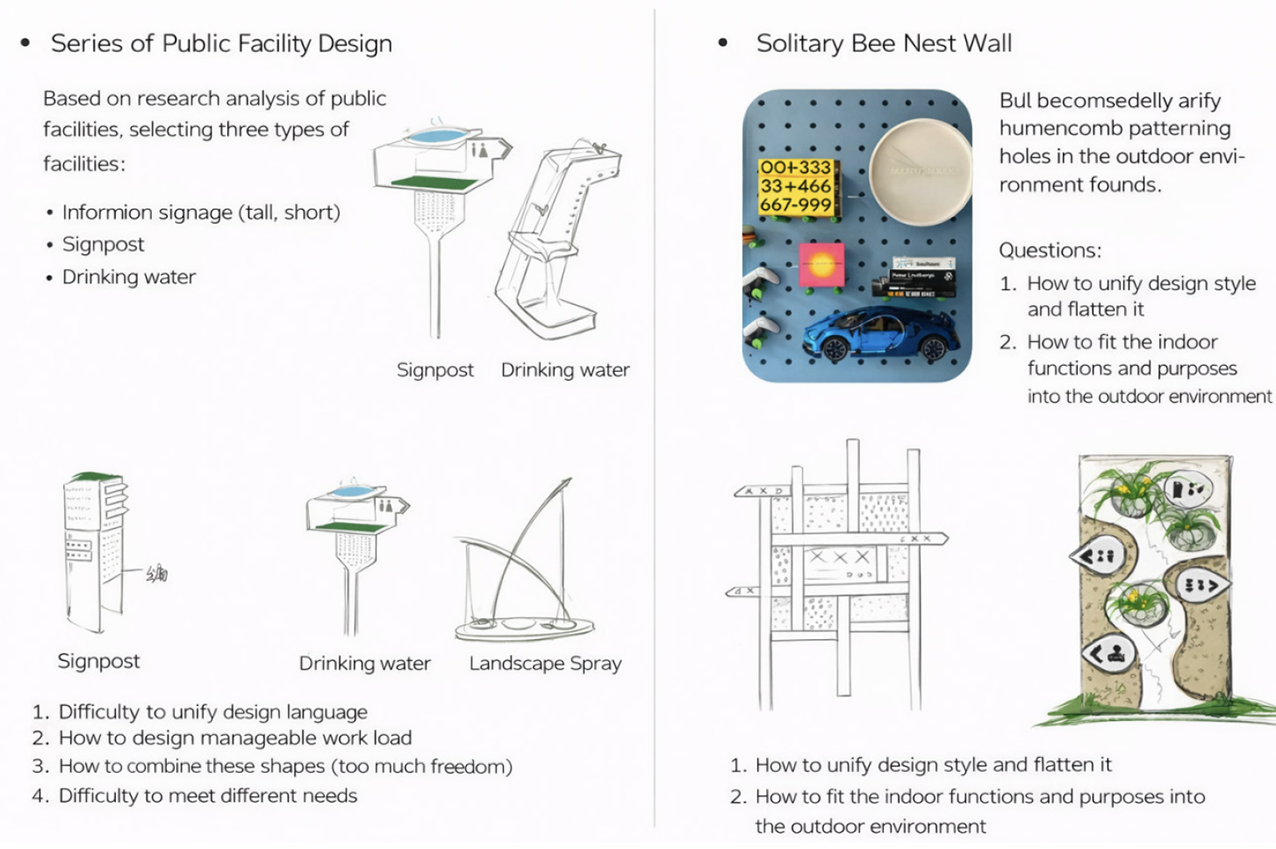

As shown on the left side of Figure 13, the author experimented with designing and innovating a series of public facilities. Based on the previous analysis of public facilities, sketches were developed for information boards, wayfinding signs, drinking fountains, and water features. However, solitary bees are not suited to coexisting with a large number of public facilities, as such locations may be too exposed to human activity, and bees are unlikely to choose sites that remain constantly visible to people for nesting. The feasibility of this approach is therefore low.

As shown on the right side of Figure 13, the author drew inspiration from holes, noting the visual similarity between the cavities of bee nests and perforated walls. The aim was to combine the formal language of perforated walls with that of bee nests. However, in outdoor settings, the connections between such holes are prone to problems, with safety not guaranteed. Additionally, the design language is overly singular and lacks diversity.