Ageing of Environmental Facilities

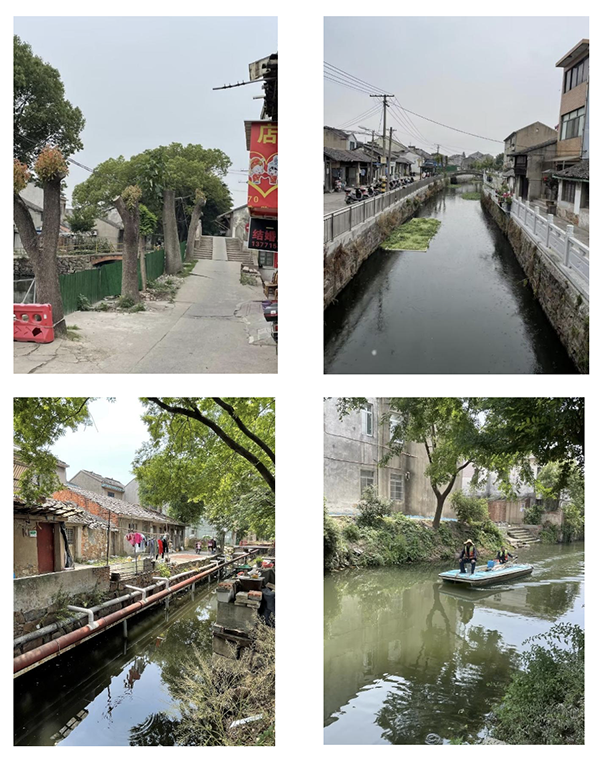

As a traditional historical district located in the south of Wuxi where the transportation network (highway) extends in all directions, Southern Spring Town has a close relationship with the outside world and is a self-contained residential community distributed along both sides of a river. During a visit, we found that the houses on both sides of the district were seriously aged, and the uninhabited houses were dilapidated. Southern Spring Town retains the most typical characteristics of Jiangnan Water Town, mainly arched brick bridges, and the residential buildings on both sides of the river are in a state of maintenance to varying degrees (Figure 1).

Research statistics show that Southern Spring Town has a total of 33 traditional wooden buildings (including 1 historic building) and 96 modern new-style buildings (including 2 tube-shaped apartment buildings and 7 buildings combining old and new styles) on both sides of the main east‒west and crisscrossed north‒south channels of the riverfront.

In the homes of local residents, living infrastructure such as running water, flush toilets, gas pipelines and sewage pipelines have been installed. In the evening, the streetlamps in the district can provide illumination for pedestrians, but the uneven road surface in the district is a problem commonly reported by residents. The sidewalks along the river in Southern Spring Town are connected by several brick bridges that cross the river.

Changes Before and After River Management

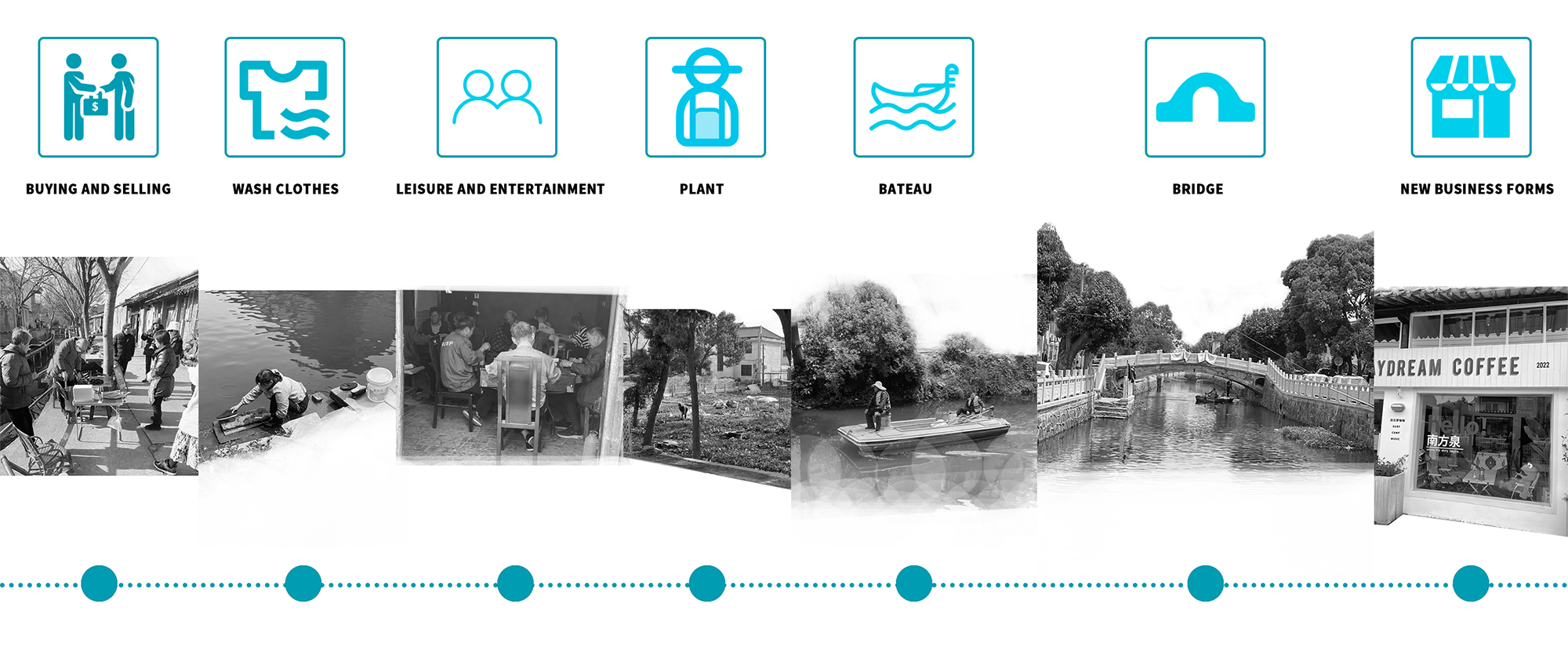

The river in Southern Spring Town still plays a role in the infiltration, leakage, and drainage of rainwater during the annual flood season, and there are staff taking boats to clean the river. From the current situation of river channels, it can be seen that Wuxi’s urbanization has a significant impact on Southern Spring Town: some river channels in Southern Spring Town have been buried due to the surrounding real estate construction and other reasons. For example, the southward river channel of the district is not connected with the Taihu Lake water system, and the west and east rivers are connected with the Chang-guang River water system. In the early investigation in October 2020, the river in the district was in a state of static and slow flow internally. In addition, both sides of the river were vulnerable to domestic sewage injection, the water quality of the river was poor, and the peculiar smell was obvious in summer. A survey in May 2023 found that sewage pipes had been installed on the inner side of the river in Southern Spring Town, basically eliminating the phenomenon of household sewage entering the river. The river is rich in fish resources, and the water quality has been significantly improved.

It was also found during the study that residents do not wash the same items in different locations of the river, which preserves the common way in which residents of Jiangnan Water Town use the river to wash their household items. During the study, people on both sides of the river still washed items in the river every day, and the main washing behaviours seen were washing daily necessities such as mops, vegetable baskets, and foot mats. At the riverside, there is also a “Six Prohibitions” notice issued by the Southern Spring Town market town management department (Figure 3). This finding shows that the district’s daily management and routine maintenance are still being implemented, but the ageing of the district’s facilities and the dilapidated buildings in the district make it easy for people to ignore the efforts of the management department.

“Self-Driven Power” in the Sustainable Social Innovation Design of Ageing Districts—Based on an Investigation into the Southern Spring Town Historical District in Wuxi

Ageing Is Serious, But Elderly People Generally Participate in Online Socializing

The diversification of employment forms in “villages on the urban fringe” and changes in social structures, such as the frequent migration of migrants, have made the characteristics of empty-nest urban villages and ageing more obvious [40]. Those who stay in Southern Spring Town are mainly elderly people who have lived here for a long time and have retired, and the ageing phenomenon is serious. Due to reasons such as work and school, most of the young people who grew up in the district have moved to a city. Because the district is located at the edge of a city, elderly individuals often get together to communicate with each other by playing cards and mahjong, which is also a common mode of leisure and entertainment in ageing communities. During the investigation, it was found that several houses were used as mahjong rooms, and the elderly people in houses gathered at several tables to play mahjong (Figure 1).

Henri Lefebvre argued that the expansion of urban space also includes the expansion of cyberspace, and the development of the internet is closely related to the process of urbanization [41]. As the city boundaries continue to spread to the fringes, the internet is also becoming popular in the suburbs at an alarming rate. This finding was also evidenced in the research that due to the popularity of smartphones. Local residents over the age of 60 are not using senior citizens’ cell phones, which can only make calls and have simple functions. These residents are generally able to skilfully use their smartphones to participate in online social activities and even as active users on social platforms. They generally keep in touch with their families and friends in real time through social media programs such as WeChat and TikTok. Taking a 79-year-old local resident interviewed in the research as an example, he has not left the local area even after his retirement and has lived here for more than fifty years. Not only was this old man able to skilfully introduce us to the floriculture methods that he had learned from TikTok, but he also registered an account to frequently post videos he had shot (Figure 2). The old man usually communicates with his family members living in the city and with his grandson who is studying in Shanghai through WeChat video communication. The wide application of the internet has expanded the intergenerational interaction model and enriched the social participation and life entertainment methods of elderly individuals, which will help promote “active ageing” [42].

At the same time, this example reflects another fact: in the daily life of elderly people, their social network behaviour mostly stems from personal will. Their receptivity and comprehension are not like those of young people, but they have more time to use social networks to obtain effective information, build a network of relationships, and expand their own capabilities. Additionally, it is not necessary to design cell phones with simple functions for elderly individuals, as envisioned in current university design education. Thus, it can be seen that ageing does not mean incapacitation. The reason is that ageing is the result of healthy lifestyles and improved medical care, and ageing also means that social welfare and quality of life have generally improved.

Introduction

According to data released by the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China, the number of historical and cultural districts designated nationwide in 2019 was 875, and by the end of 2021, it had increased to 1200 [1]. Most of these historical districts exist in the form of “villages on the urban fringe,” embodying urban history and regional diversity, and the “wicked problem” faced by contemporary urban development has become increasingly prominent.

This research takes “villages on the urban fringe” of Wuxi, specifically the Southern Spring Town Historical District, as the research object and discusses the transformation of the district from a gradual decline to the emergence of internal self-driving power in the district under the background of ageing. Southern Spring Town, formerly known as an ancient well, was part of Kaihua Township from the Song Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty and was named after “Kaihua Square Well.” At present, the district is facing a “wicked problem” intertwined with factors such as ageing residents and sustainable development. This study takes this district as an example to carry out a series of surveys (5 surveys conducted from October 2020 to May 2023), trying to reveal the influencing factors of existing problems by describing the current situation and comparing the factors before and after river management.

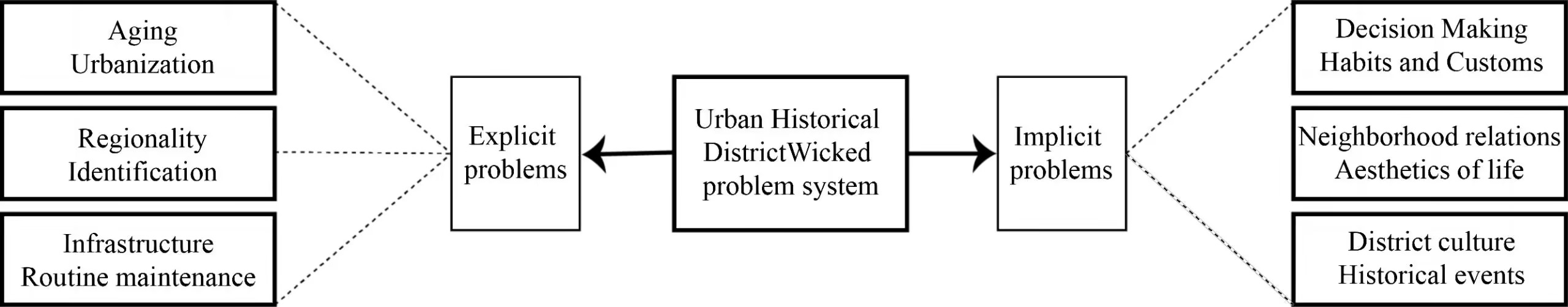

In this study, we analyse different factors, such as the district’s regional characteristics, living environment, neighbourhood, customs, and culture, which are classified into explicit and implicit categories to be included in the structure of the “wicked problem.” Through this study, we believe that the design and planning of historical districts need to emphasize districts’ self-driven power, avoid excessive commercial development patterns and environmental regeneration, and leave space for the sustainable development of historical districts to be self-regulated.

In the physical spatial system of a historical district, there is also a dynamic humanistic ecological system that integrates the essence of regional culture and life wisdom [29]. “Dynamic” means that the historical district is constantly incorporating new blood and conforming to the city’s metabolism. The protection and utilization of a historical district play an irreplaceable role in economic and cultural continuity [30]. The subject of this continuation is not some specific objects but some events or behaviours that can show typical local humanistic characteristics [31]. There has been a tendency among both researchers and practitioners to highlight tangible values, such as architectural elements, over intangible values, such as emotional, social, cultural, and psychological connections between humans and the landscapes that they inhabit [32].

There are also in-depth discussions on the internal relationship between historical districts and cultural recognizability, and the direction and results of the discussions are also consistent. Fang Jingcheng argued that the most important aspect in the protection of historical and cultural districts is the protection and maintenance of the recognizability of a city [33]. Amer M B K B proposed that a district is a local community and is a fundamental tool for globally managing urban heritage and strengthening cultural identity and the sense of belonging [34]. Djamel Boussaa argued that urban regeneration can respond to social issues such as the mass displacement of residents and gentrification by gradually dealing with rational and emotional urban issues such as historical districts and central gentrification [35]. Revitalizing historical neighbourhoods can play an important role in protecting urban historical and cultural environment resources and maintaining urban identity and recognizability.

Different from the early stage of China’s reform and opening up in the 1980s, urban renewal at this stage is mainly driven by profound changes in China’s socio-economic structure rather than the physical ageing of cities. In 2021, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China announced the first batch of 21 city renewal pilots, two of which are worth noting: one encourages the participation of the public and social capital, and the other emphasizes that “retain, utilize and improve” is the principle [36]. The renewal and protection of traditional historical districts are important parts of urban development. Their economic role is self-evident, and the value of maintaining urban characteristics and strengthening regional recognition is increasingly recognized. In summary, based on existing research, this paper studies the “self-driven power” of social innovation in historical districts under the trend of ageing from the perspective of urban sustainable development, regionality, ageing and cultural recognizability.

Abstract

This study examines the problems faced by decision-making regarding sustainable social innovation through field research in “villages on the urban fringe,” represented by the Southern Spring Town Historical District in Wuxi. On the premise of protecting urban diversity and cultural recognizability, the “wicked problem” factors that affect the protection and innovative design of the historical district and their framework are analysed by comparing the explicit and implicit factors of the district. This study finds that the residents of this district have undergone spontaneous renewal and changes driven by increasing foreign tourists. These changes are not the result of guidance by government planning and management, nor are they promoted by designers. Additionally, the residents of the Southern Spring Town Historical District generally recognize the unique value of the district’s historical and humanistic landscape. Self-driven power makes the residents’ meaning of environmental protection increase. They actively engage in catering and cultural business activities with Jiangnan regional features. Worries over the district’s lack of successors no longer exist, and a new hope for sustainable development has been gained. We believe that before using planning tools and design thinking to solve the problem of ageing historical districts under the trend of sustainable development, it is necessary to have a deeper understanding of the actual operation of such districts and their real needs and to allow time and space for local residents to solve the “wicked problem” through self-regulation to ultimately achieve the long-term goal of district preservation and sustainable development in a balanced manner.

The Ecology of The District: The Paradox of Innovation Integrated into Urban Development

The innovation and development of new and old areas in a city should have different models. If the old regional development model is replaced by a new district, it will inevitably lead to the loss of the culture and regional ecology of a historical district. In The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs discussed urban diversity and mutually supportive district ecologies and indicted the shortsightedness and arrogance of functionalist tendencies in orthodox urban planning. She pointed out that urban plans—whether Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City or Le Corbusier’s Radiant City—are based on not the actual experience and needs of a city and its community life but a rational construction based on function [43].

The governance and planning of Southern Spring Town are also chaotic and have no clear positioning. Jane Jacobs affirmed the advantages of convenience, social interaction, and the pursuit of effective help in the daily life of old communities in the development of American cities, and Southern Spring Town also has these advantages. While Southern Spring Town has become a microcosm of the city’s past, it does not detract from the basics that make it a community integrated into the city’s modern life, such as an in-house kiosk, a supermarket, a barbershop, a restaurant, and a pharmacy, as well as transportation links to the outside and a 5G base station.

Applying new urban district management thinking and measures to a historical district such as Southern Spring Town is not only ineffective but also irreparably destructive. The commercialization of historical districts is currently a common development model. Since urbanization construction dominated by commerce and service industries is not consistent with the non-commercial environment of a historical district and because there is even a large difference in the paradigm of daily life, it is impossible to carry out renovation and reconstruction with the goal of integrating the historical district into the city or incorporating this type of district into the structure of the city’s commercial service industry. It will be operated by social capital, similar to Xun-tang Ancient Town in Wuxi, and eventually evolve into a mixture of homestays and pedestrian street-style internet celebrity tourist spots. One of the development paradoxes that the historical district has fallen into is that to achieve development, it is necessary to change the existing mode of existence, and for the sake of commercial interests, it is necessary to carry out artificial packaging and construction and add external decorative and fashionable elements, which, as a result, leads to even more serious damage. In fact, this kind of damage caused by “human factors” has been verified after the maintenance of Southern Spring Town: a large tree was sawn down, sewage pipes were installed in the river (rain and sewage diversion), and quality guardrail of stone were installed by the river. Although the problem has been solved, new secondary problems have been created, all of which reflect the damage to the original natural and cultural environment of the water town (Figure 4).

The research also found that the views of elderly individuals were not unanimous on the issue of continuing to live here or hoping to move out after demolition. They are mainly divided into several categories: 1. They hope to move out earlier. This type of resident expects the government to demolish and relocate residents soon and receive compensation. 2. They hope to live in the district all the time because there are decades-long friendships and a familiar environment here, the air is good, and life is leisurely, and the residents are not too adapted to the hustle and bustle of life in the city. 3. They are in a state of hesitation. On the one hand, they cannot leave the neighbourhood; on the other hand, they feel uneasy because of the ageing district.

Overall, the development dilemma faced by Southern Spring Town is somewhat similar to that of historical districts in other cities. Although the government planning management and street management departments all attach importance to the non-renewable value of the historical district and its cultural significance to the city, regardless of whether it is a commercial street or a homestay model, all parties can reach a consensus to solve such problems. As a result, the historical district also reflects its own regulation mechanism. On the one hand, under the publicity of self-media, due to the increase in tourists who come here for fame, the spontaneous business behaviour of the residents of the district has given the district new vitality. On the other hand, the business of family stores also attracts the children of elderly individuals to return to help manage these businesses, showing new changes in the planning of non-government departments. In this context, the problem of no successors in the district is no longer a problem in Southern Spring Town. The new problem is how to maintain and effectively manage the commercial behaviour of residents in the district.

That is, in the context of urban sustainable development, the historical district has changed from the original unsustainability to sustainable development through the intervention of external factors. As Robert Putnam put it in Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, the connections among individuals, i.e., social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them, increase civic engagement, leading to greater social capital, which in turn provides the basis for effective government and economic development [50]. Civic engagement here is placed in the context of Southern Spring Town, which can be regarded as the wicked problem faced by the historical district. That is, through the external forces of non-government planning departments, the original difficulties caused by development may be resolved, but it is necessary to pay attention to the importance of spontaneous factors in problem solving. Through the comparison of explicit and implicit factors, the wicked problem framework model of historical district protection and innovative design provides a reference for the orderly solution to complex system problems (Figure 6).

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Current Situation and Problems

- The Ecology of The District: The Paradox of Innovation Integrated into Urban Development

- Governance Dilemma: The “Wicked Problem” Faced by the Development of Historical Districts

- Conclusion

- Author Contributions

- Conflicts of Interest

- Funding

- References

Meng Liu 1 ,

by

1 School of Design, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JDSSI. 2023, 1(3-4), 16-33; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jdssi2023.1227a11

Received: November 21, 2023 | Accepted: December 20, 2023 | Published: December 27, 2023

Urbanization and Semi-Urbanization

The term “semi-urbanization” is used to describe the uneven resources and uncoordinated development in the process of urbanization, which in China also restricts the permanent settlement of migrant workers in cities through the household registration system [49]. The phenomenon of “semi-urbanization” in Southern Spring Town is worth discussing: 1. There is a transportation network connection with the core area of the city. 2. Residents in the district basically have the supporting facilities of urban residents in their homes (natural gas, tap water, toilets, etc.). 3. The street-based management model of urban residents has been realized. 4. Administrative management is still under the purview of townships. Integration into urban development is a common measure for solving the problem of “villages on the urban fringe,” especially the attempt to gradually commercialize historical districts, which has been fully discussed in existing practice and research.

In summary, urbanization and semi-urbanization are the result of complex factors in urban development, and this phenomenon of the varying pace of life is in fact a reflection of the richness of urban life. Semi-urbanization is not urbanization in waiting, nor is it a burden of urbanization, but it is itself a supplement to urbanization.

Governance Dilemma: The “Wicked Problem” Faced by the Development of Historical Districts

The “wicked problem” of Southern Spring Town is divided into explicit and implicit parts for comparison, and it is found that the implicit factor describes the district in a way that is more in line with the cultural demands of contemporary people for historical districts, for example, the history of “Kaihua Square Well” and the everyday lifestyle of local people, the traditional style of bridges, Phoebe architecture and the horse head walls of residential buildings. There is a close relationship between explicit and implicit factors, and changes to explicit elements will inevitably cause destructive effects on implicit elements.

The Dilemma of Long-Term Governance

In our survey in October 2020, we believed that, at the time, Southern Spring Town was in a predicament that hindered its development because, at the time, the district was supported by left-behind elderly individuals, not only lacking vitality but also facing the problem of no successors. Since Southern Spring Town has a large number of elderly people over the age of 70, in the next 20-30 years, if the elderly people who remain behind gradually pass away and if no young people return to live in the district, the environmental conditions in the district will fall into the predicament of having no one to succeed the current elderly residents if there is no improvement. This means that if the planning and management departments do not carry out the necessary construction and management of this historical district, they will not change the “hollowing out” trend of Southern Spring Town.

Although the community has attracted some migrant workers to live in it, this group is relatively mobile and has had many conflicts with local residents in terms of daily life (such as garbage disposal and river cleaning), and the neighbour relations have been antagonistic. These two groups not only have large differences in their everyday lifestyles but also exacerbate the difficulties in district public security management and environmental sanitation maintenance.

Because elderly people in the district, like traditional buildings, carry away the historical information of the district, the renovation of a new commercial model, although sustainable in maintaining the vitality of the district, is limited to the material level of explicit commercial consumption. The implicit elements will be modified without leaving any trace, presenting a “stuck problem” in the development of the historical district. That is, regardless of what protection measures for Southern Spring Town are taken, the district will irreversibly become the result of no sustainable residential buildings and serious ageing of the district’s housing in the next 20-30 years. Therefore, neither the government planning management department nor the residents of the district are willing to invest the financial and material resources to maintain and repair the dilapidated houses and facilities related to daily life in the district.

During the May 2023 study, Southern Spring Town saw an unanticipated new development opportunity: as an increasing number of tourists came to Southern Spring Town to visit and enjoy themselves in the town, local residents began to operate local specialty snacks out of their homes. The children of elderly individuals also returned on weekends to help run businesses, presenting an emerging spontaneous order within the district. The emergence of this small commercial business model has revitalized the district (Figure 5).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.W. and J.C.F; Field research, M.W.; Visualization, M.W., M.L. and X.K.Z.; Writing—original draft, M.W; Writing—review and revise, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Historical District 2.0: Sustainability and Recognizability

Urbanization 2.0 corresponds to historical district 2.0. Urbanization and historical district protection go hand in hand, and the sustainable development and recognizability of cities and their historical districts share the same goals. Urbanization 1.0 is the infrastructure stage of rapid urbanization, which is part of the construction of rigid infrastructure and supporting services. Urbanization 2.0 should take into account the cultural environment of a historical district, treat the industrial characteristics and cultural advantages of each region in a differentiated manner, strengthen diversity construction that is compatible with traditional and contemporary culture, and focus more on the construction of a flexible cultural level. For example, adopting more attitudes towards inclusiveness and diversity maintains the recognizability and cultural typicality of a historical district. Especially in fast-paced urban life, it is necessary to integrate a historical district with a slow pace of life as a way to relieve the pressure of urban life and provide a place for the in-depth experience of urban history and culture. The Charter of New Urbanism mentioned that communities, districts and urban corridors are the basic elements of urban development and regeneration. They form recognizable areas that encourage citizens to take responsibility for their maintenance and development [51].

The urbanization process of Wuxi is similar to that of other cities in China. In the process of coping with the ageing trend and moving towards sustainable development, as a typical eastern city, the phenomenon of “over-urbanization” should be prevented. The new district and the old district in the city have different life rhythms, environmental orders, and urban roles, but both have sustainable and recognizable development requirements, embodying the new paradigm of “unity but difference” in historical district 2.0.

Urbanization 2.0 is the foundation of historical district 2.0. At this stage, it is not necessary to demolish or transform an old city into a new city and integrate it into the new city. Instead, it is necessary to grasp the diversity and historical factors of the old city and the new city, as well as contemporary life, to achieve a harmonious relationship between the two systems of the new city and the historical district to realize a positive complementarity. For example, the large trees sawn down due to the construction of a civilized city in Southern Spring Town, the newly repaired river guardrails and the paved asphalt pavement have become a kind of damage to the city’s cultural and historical heritage. Urbanization should reflect the regional and cultural characteristics of cities. Instead of developing traditional historical districts through urbanization, we must take differentiated measures to develop cities.

Therefore, the use of historical districts as a diversified form of differentiating and regulating urban rhythms not only requires the acceptance of the existing order of life and the logic of operation under the influence of the regional culture of such districts but also allows them to continue to maintain the rhythm of life that has already been fixed, rather than accelerating their integration into the fast-paced pace of the city through policy interventions.

Community Cohesion: Acquaintance Communities as Traditional Neighbourhood Ties

Urbanization has reconstructed the structural space of the city, and it has also reconstructed a new relationship between people. The community has gradually changed from an acquaintance community to a stranger community, and the geographical, blood, and kinship relationships that are the ties of interpersonal relationships are gradually being replaced by modern business, interest, and profit relationships [44]. Southern Spring Town is a “semi-urbanized” community of acquaintances. Although there are highly mobile foreign tenants living there, the original cohesion of the district has not been eliminated, which is undoubtedly due to the long-term accumulation of neighbourly relations. Residents’ original social relations have not been quickly detached from the geographical association of mutual interaction, and their behaviour has not shown the characteristics of spontaneous “disembedding” [45]. The social structure is very different from homeowners’ communities of strangers from all over the world who do not interact with each other in commercial housing neighbourhoods driven by urbanization. In sociology, there are two kinds of societies of different natures: one has no specific purpose and only because the society formed solely by people living together; the other is a society that comes together to accomplish a task. Durkheim refers to the former as “organic solidarity” [46]. Therefore, the new model and method of urbanization cannot be used to re-plan this traditional historical district, which will destroy the inherent structure that has been spontaneously generated within it and the relatively stable neighbourhood relations that have already been established. Regardless of how well-intentioned the planners are, they cannot simulate the structural relationships that are spontaneously formed in the daily life of traditional districts (Figure 3).

A basic manifestation of community safety is that people must feel safe when they are among strangers on the street and must not subconsciously feel threatened by strangers [47]. This has been validated in Southern Spring Town: as most of the residents interviewed are local residents, they have formed a well-known district public life and security network through years of continuous contact and interaction. The visit also found that some stores in the district that operate year-round, such as grain, oil, and catering establishments, not only provide daily necessities but also maintain the order of public life to a certain extent. The reason is that shops distributed in different locations in the district act like “eyes on the street,” invisibly playing a role in supervising public safety [48].

The neighbourhood relations in the acquaintance community have formed a relatively stable model that can well maintain local security and other issues, and residents can unanimously safeguard the interests of the community itself.

Current Situation and Problems

In China’s urbanization development, there are three kinds of villages that coexist in the national urbanization process, namely, villages on the urban fringe, urban villages, and rural areas [37]. Some researchers believe that suburban urbanization is the process of realizing the transformation of lifestyle from rural to urban and gradually reducing the differences in production and living conditions between urban and suburban areas [38]. The trend of suburban urbanization is a severe challenge to diverse and coexisting regional cultures, and whether Southern Spring Town can retain its own “recognizability” in the process of Wuxi’s urbanization is also a question that urgently needs to be addressed.

After Fei Xiaotong investigated Zhenze Ancient Town in southern Jiangsu, he summarized three specific issues: 1. the noise pollution and management problems caused by the mixed factory area and residential area; 2. the water network system and water quality of the ancient town were affected; and 3. the further spread of pollution due to industrialization [39]. The 2022 Wuxi Municipal Government Work Report pointed out that the implementation of urban renewal planning guidelines and design management methods will renovate 8.93 million square metres of old communities, which is close to the sum of the “13th Five-Year Plan” period, and 494 old communities will achieve full coverage of state-owned properties, benefiting 250,000 households. Under the background of the transformation of the “Southern Jiangsu Model,” Southern Spring Town and the overall development of the city show an inconsistent rhythm, which is manifested in the following: the migrant population is employed and rents houses here for a long time, which increases the difficulty of governance; public service facilities are insufficient; local residents are ageing to a serious degree, and community vitality is in decline; and the “man-made damage” to the buildings, landscape environment, and rivers in the area leads to the disappearance of regional cultural characteristics. It is under this background that, based on several field investigations and interview records on the daily life conditions of residents of Southern Spring Town over the past two years (October 2020-February 2023), this study attempts to analyse relevant issues at home and abroad. On this basis, a framework model of the “wicked problem” elements of Jiangnan’s traditional historical district social innovation design is further proposed to promote in-depth research on such “wicked problems.”

Southern Spring Town was once the cultural centre of southern Wuxi and is a typical “urban village.” As a historical district spread along both sides of a river, the area has now become an island-style “urban village” surrounded by commercial real estate and housing projects. The main task of the project research is to investigate the current situation and problems of Southern Spring Town, trying to understand the existing problems and influencing factors of the district through the real situation of the district and the relatively stable everyday lifestyle.

Xiongkai Zheng 1 ,

Jiancai Fan 1 ,

Min Wang * 1

Literature Review

The development of historical districts is influenced by multiple factors, such as politics, the economy and culture. The study of historical districts, that is, the exploration of their physical space and the process of human social development over a certain period of time in the past, encompasses both the material and immaterial aspects of the architecture, landscape, culture and customs of historical districts. As stated in the ICOMOS Washington Charter (1987), beyond their role as historical documents, these areas embody the values of traditional urban cultures.

Using “historical district” as the search term in Google Scholar, 3 million documents were displayed. In the CNKI database, using “traditional, historical district” as the search term on May 7, 2023, we obtained 655 journal papers, 441 dissertations, and 106 conference papers. The data show that research in the field of construction engineering and science is dominant (more than 80%), and the number of published papers reached a peak in 2020 (96).

In previous research, the main topics were historical district protection [2, 3, 4], historical districts and sustainability [5, 6, 7], urban space reorganization and renewal [8, 9, 10], and historical districts and urban management [11, 12, 13]. In addition, the urban landscape [14, 15] and cultural heritage protection [16, 17] have received attention. Contextualism [18, 19, 20], organic renewal theory [21, 22, 23], Micro-renewal theory [24, 25], and sustainable development [26, 27, 28] are theories that are often mentioned in related research.

© 2023 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Meng Liu, Xiongkai Zheng, Jiancai Fan, and Min Wang, "'Self-Driven Power' in the Sustainable Social Innovation Design of Ageing Districts—Based on an Investigation into the Southern Spring Town Historical District in Wuxi." JDSSI 1, no.3-4 (2023): 16-33.

AMA Style

Meng Liu, Xiongkai Zheng, Jiancai Fan, and Min Wang. “Self-Driven Power” in the Sustainable Social Innovation Design of Ageing Districts—Based on an Investigation into the Southern Spring Town Historical District in Wuxi. JDSSI. 2023; 1(3-4): 16-33.

References

1. Wuxi County Records Compilation Committee, Wuxi County Records (Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences Press, 1994), 119.

2. Jinghui Wang, “Problems and solutions in the protection of historical urban areas,” Frontiers of Architectural Research 1, no. 1 (2012): 40-43. [CrossRef]

3. Naciye Doratli, Sebnem Onal Hoskara, and Mukaddes Fasli, “An analytical methodology for revitalization strategies in historic urban quarters: a case study of the Walled City of Nicosia,” North Cyprus 21, no. 4 (2004): 329-348. [CrossRef]

4. Yisan Ruan, “Protection and Planning of Historical District,” Urban Planning Forum, no. 2 (2000):46-47+50-80. [cnki]

5. Chris Landorf, “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17, no. 5 (2011): 463-477. [CrossRef]

6. Beser Oktay Vehbi, and Şebnem Önal Hoşkara, “A model for measuring the sustainability level of historic urban quarters,” European Planning Studies 17, no. 5 (2009): 715-739. [CrossRef]

7. Hui Li, and Hongwei Ding, “Sustainable Development of Historical District Protection,” Planners, no. 4 (2003):75-78. [cnki]

8. İclal Dinçer, “The impact of neoliberal policies on historic urban space: Areas of urban renewal in Istanbul,” International planning studies 16, no. 1 (2011): 43-60. [CrossRef]

9. Rebecca Madgin, “Reconceptualising the historic urban environment: Conservation and regeneration in Castlefield, Manchester, 1960-2009,” Planning Perspectives 25, no. 1 (2010): 29-48. [CrossRef]

10. Ke Fang, “Exploring the Appropriate Ways of Organic Renewal of Residential Areas in Beijing’s Old City” (Ph.D. thesis, Tsinghua University, 2000). [cnki]

11. Dennis Rodwell, “Urban morphology, historic urban landscapes and the management of historic,” Urban Morphology 13, no. 1 (2009): 78-79. [CrossRef]

12. Lei Qu, “Urban Management Strategies in the Process of Gentrification of Old City,” Journal of Urban and Regional Planning, no. 3 (2010):172-183. [cnki]

13. Arturo Azpeitia Santander, Agustín Azkarate Garai-Olaun, and Ander De la Fuente Arana, “Historic urban landscapes: A review on trends and methodologies in the urban context of the 21st century,” Sustainability 10, no. 8 (2018): 2603. [CrossRef]

14. Silvio Mendes Zancheti, and Rosane Piccolo Loretto, “Dynamic integrity: a concept to historic urban landscape,” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 5, no. 1 (2015): 82-94. [CrossRef]

15. Francesco Bandarin, “From paradox to paradigm? Historic urban landscape as an urban conservation approach,” Managing cultural landscapes, (2012): 213-231. [CrossRef]

16. Meysam Deghati Najd, Nor Atiah Ismail, Suhardi Maulan, et al, “Visual preference dimensions of historic urban areas: The determinants for urban heritage conservation,” Habitat International 49, (2015): 115-125. [CrossRef]

17. Mingxin Zhang, “Operating a city historical district” (Ph.D. thesis, Tongji University, 2007). [cnki]

18. Junqiao Sun, “Towards New Contextualism” (Ph.D. thesis, Chongqing University, 2010). [cnki]

19. Shangyi Zhou, and Shaobo Zhang, “Contextualism and sustainability: a community renewal in old city of Beijing,” Sustainability 7, no. 1 (2015): 747-766. [CrossRef]

20. Soroush Masoumzadeh, and Hadi Pendar, “Walking as a medium of comprehending contextual assets of historical urban fabrics,” Urban Research & Practice 14, no. 1 (2021): 50-72. [CrossRef]

21. Wu Liangyong, Beijing Old City and Ju’er Hutong (China Architecture and Building Press, 1994).

22. Lian Wu, and Dan Shen, “Research on Organic Renewal and Vitality Rejuvenation of Historical District——Taking Qinghai Tongren Democracy Shangjie Historical District Protection Planning as an Example,” Urban Development Studies, no. 2 (2007):110-114. [cnki]

23. Dong Quan Li, “Revitalization of Historic Streets under the Perspective of Organic Renewal,” in Education and Awareness of Sustainability: Proceedings of the 3rd Eurasian Conference on Educational Innovation 2020 (ECEI 2020), (2020), 693-696.

24. Haifeng Chu, Yimei Meng, and Shuhua Huang, “Study on the Vitality Enhancement and Environmental Intelligence Technology of Historical and Cultural Neighborhoods Based on Organic Renewal Theory: Jinan Mingfu City as an Example,” in 2022 2nd International Conference on Public Management and Intelligent Society (PMIS 2022), (Atlantis Press, 2022), 29-37. [CrossRef]

25. Lu Ye, Liang Wang, and Chang Wang, “‘Micro Renewal’ of Historical and Cultural District——Research on the Design of Dongsantiao Camp in Laomen, Nanjing,” Architectural Journal, no. 4 (2017):82-86. [cnki]

26. A. Boeri, D. Longo, V. Gianfrate, et al, “Resilient communities. Social infrastructures for sustainable growth of urban areas. A case study,” International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning 12, no. 2 (2017): 227-237. [CrossRef]

27. Chris Landorf, “Evaluating social sustainability in historic urban environments,” International Journal of Heritage Studies 17, no. 5 (2011): 463-477. [CrossRef]

28. Yuxiang Ruan, and Peng Xu, “Environmental renewal and sustainable development of traditional historical districts,” Engineering Journal of Wuhan University, no. 5 (2002):67-69. [cnki]

29. Shaoping Ding, and Mingsheng Sun, “Analysis on the Typological Strategy of Historical District Architectural Style Renewal from the Perspective of Regional Context Inheritance——Taking Nanbei Street, a famous historical and cultural city in Xunxian County as an Example,” Industrial Construction 52, no. 6 (2022): 47-54. [cnki]

30. Yanqing Sun, Green Urban Design and Its Regionalism Dimension (Ph.D. thesis, Tongji University, 2007), 155. [cnki]

31. Jianxin Diao, Research on Cultural Inheritance and Diversified Architectural Creation (Ph.D. thesis, Tianjin University, 2010), 78. [cnki]

32. Fatmaelzahraa Hussein, John Stephens, and Reena Tiwari, “Towards psychosocial Well-Being in historic urban landscapes: the contribution of cultural memory,” Urban Science 4, no. 4 (2020): 59. [CrossRef]

33. Jingcheng Fang, “Recognizable Protection of Famous Historical and Cultural Cities and the Case of Jinhua,” Urban Development Studies, no. 1 (2008):108-111. [cnki]

34. Mohamed Badry Kamel Basuny Amer, “Cultural Identity: Curating the Heritage City,” Retrieved March 8, (2018): 2022.

35. Djamel Boussaa, “Urban regeneration and the search for identity in historic citie,” Sustainability 10, no. 1 (2017): 48. [CrossRef]

36. Jianqiang Yang, “The Current Situation, Characteristics and Trends of Urban Renewal in China,” City Planning Review, no. 4 (2000):53-55+63-64. [cnki]

37. Wei Lang, Tingting Chen, and Xun Li, “A new style of urbanization in China: Transformation of urban rural communities,” Habitat International 55, (2016): 1-9. [CrossRef]

38. Kevin Fox Gotham, and Arianna J. King, “Urbanization,” in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Sociology (2019): 267-282. [CrossRef]

39. Xiaotong Fei, On Small Towns and Others (Tianjin People’s Publishing House, 1986), 87-88.

40. Xiaolei Ma, and Yiran Lin, “Research on the Social Activities and Public Space Characteristics of the Elderly in Urban Village,” China Urban Planning Society, Chengdu Municipal People’s Government. Space Governance for High-quality Development—Proceedings of the 2020 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (16 Rural Planning), (China Architecture and Building Press, 2021),11. [cnki]

41. Ning Wu, “Lefebvre’s Theory of Urban Space Sociology and Its Significance in China,” Chinese Journal of Sociology, no. 2 (2008):112-127+222. [cnki]

42. Yongai Jin, and Menghan Zhao, “Internet use and active aging of the elderly in China——Analysis based on the data of the 2016 China Aging Society Tracking Survey,” Population Journal 41, no. 6 (2019): 44-55. [cnki]

43. Jane Jacobs, The death and life of great American cities (New York: Vintage 321, 1992), 325.

44. Youhua Chen, and Mengfan Xia, “Modernization of Community Governance: Concepts, Problems and Path Selection,” Study & Exploration, no. 6 (2020):36-44. [cnki]

45. Zheng Bing, He Cai, Dayong Hong, et al, “‘Transformation and Development: Forty Years of Chinese Social Construction’ Written Talk,” Chinese Journal of Sociology 38, no. 6 (2018):1-90. [cnki]

46. Xiaotong Fei, Rural China (Peking University Press, 2012).

47. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American, trans. Hengshan Jin (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2005),30.

48. Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American, trans. Hengshan Jin (Nanjing: Yilin Press, 2005),35.

49. Xiang Liu, Guangzhong Cao, Tao Liu, et al, “Semi-urbanization and evolving patterns of urbanization in China: Insights from the 2000 to 2010 national censuses,” Journal of Geographical Sciences 26, (2016): 1626-1642. [CrossRef]

50. Robert Putnam, “Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community,” Journal of Catholic Education, (2004):266-268.

51. Emily Talen, New Urbanism Charter: Second Edition (Electronic Industry Press, 2016), 99.

Conclusion

The development dilemma faced by Southern Spring Town in Wuxi is undoubtedly a “wicked problem” that needs to be solved in the urbanization process of the Jiangnan city cluster. The literature suggests that previous studies have focused on the historical value and renewal of traditional historical districts, often seeking change through the intervention of external forces but neglecting the fact that the ageing historical districts themselves still have internal vitality. In the innovative design of sustainable urban districts, we cannot ignore the adverse effects of hidden factors to cater to or meet the material needs of explicit factors, which may lead to irreparable losses. In response, a “wicked problem” architecture diagram based on a historical district has been proposed to illustrate that planning, updating, and conventional governance are closely related systems. The main aspects of implicit factors are included, but further discussion is needed based on specific issues.

Summarizing the information of the series of surveys, this study believes that the “wicked problem” in the development of “villages on the urban fringe” represented by the Southern Spring Town Historical District is not that the planning management department does not pay enough attention to it or that it is unwilling to invest funds to improve the living environment of residents. Rather, the problem is how to give district residents the self-driven power for district development in the context of ageing. The impact of external factors activates the power of self-motivation of district residents, realizes the sustainable, low-intervention, and low-maintenance development of the district through internal forces, and gives full play to the district’s own advantages and cultural recognizability.

An aspect worthy of further discussion is that the image maintenance of a historical district should consider the unique environment and needs of the district to avoid the “one size fits all” phenomenon. If planning decisions lack long-term and systematic measures, irreparable losses may occur. City planners and managers need to make targeted assessments of the possible consequences of different decisions. Based on different perspectives, such as changes in human settlements, methods of social network reconstruction, the inheritance of the regional context, and changes in life and consumption patterns, research on sustainable development and social innovation in historical districts requires continuous evaluation and reflection.