“Backwards” and “advanced”

Another attitude that needs to be corrected is the long-standing prejudice towards the countryside and its culture. In contrast to the urban cultural system, rural life practices are often seen as “backward,” “old-fashioned” and “uncultured,” which is why we have such bizarre movements as bringing “culture to the countryside,” hoping to infect and replace rural “stereotypes” with the “advanced” culture of the city. However, the absurdity of this juxtaposition of “backward” with “advanced” can be illustrated by the sensation caused by a paper-cut creation by Gao Fenglian, a peasant in northern Shaanxi:

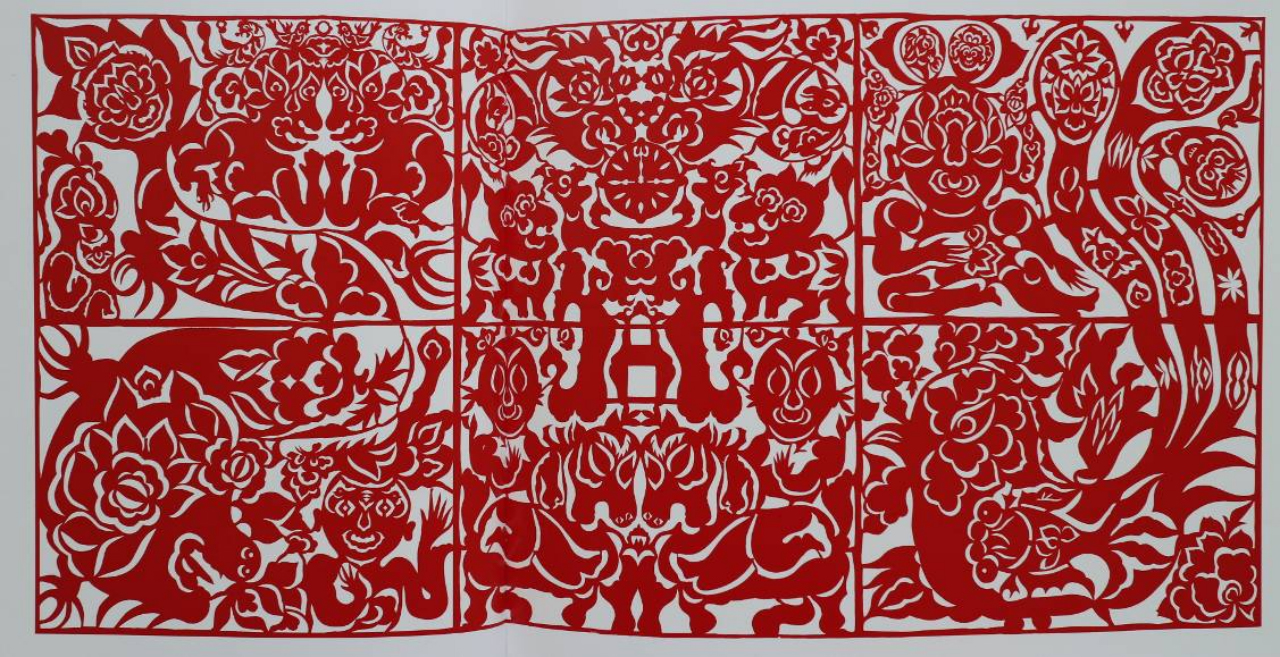

When the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women was held in Beijing in 1995, the Chinese Ministry of Culture, through experts from the Central Academy of Fine Arts, invited Gao Fenglian and three other paper cutters from the loess plateau to present an exhibition of Chinese women’s culture and art at the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Before the opening of the exhibition, Gao Fenglian was given the task of cutting a large piece of work representing the theme of the Women’s World Conference, which later brought worldwide attention to her paper-cut, The Pailou (Figure 4). The work follows the symbolic language from the totemic culture period as a method of viewing objects and making images but presents a new conceptual art form with realistic descriptions and romantic expressions that incorporate a certain will of the modern state into the thousand-year-old beliefs of the village. The amazement of the participants, who were of different colors and cultural backgrounds, came from the modern beauty of the work, which no one could argue as coming from a “backward” and “outdated” cultural ecology [3].

In the small Cheng village on the Yellow River in northern Shaanxi, elderly women can still be seen cutting paper and singing local folk songs at the same time. They are happy and enchanted by engaging in a folkcraft activity with a legacy and a tradition of recording wonderful life experiences, and their works mostly express the reality of their own lives. The creation and use of folk art not only contains the spiritual beliefs of the people but also the aesthetic experiences of their lives. Their need for such experiences is exactly the same as the ancient Chinese literati and scholars who expressed lyrical and personal feelings through chanting poetry, reciting words, drawing calligraphy, and making paintings. Therefore, if we value and enhance the artistic value of folkcrafts in our cultural strategy, truly treat these practices as the magnificent art of traditional Chinese culture, and eliminate the sense of “backwardness” that has stigmatized its surviving groups over the years, these traditional practices will still be a living culture and will not fall into the “heritage” category.

Unfortunately, when we compare rural and urban areas together today, we are still comparing “backwardness” and “advancement.” It is undeniable that the methods of production represented by urban industrialization are more advanced than nonmechanized farming methods and that industrial production inevitably entails changes in agricultural techniques, but this does not mean that cultural “urbanization” is necessary and that full-scale “urbanization” will inevitably happen once again. Ultimately, the whole culture of Chinese farming, based on manual labor, will become a “legacy” that is extinct.

Although many scholars have examined the sequential relationship between the practical and aesthetic aspects of human creation from a variety of disciplines, this is not the key to exploring the survival of folk art. The consideration of the aesthetic need to promote or resurrect folk art is based on the study of logical reasoning about its utilitarian nature. As traditional rural life enters industrial civilization, this logic will also reason out the demise of folk art as utilitarian ideas about survival, profit, and avoidance of harm recede in folklore. Originally, in folk art and folklore activities, utilitarian pursuits went hand in hand with aesthetic needs, or at least, utilitarianism did not outweigh aesthetics.

Today, since we cannot change the transformation of the so-called “feudal superstition” by scientific civilization, we should study and promote the aesthetic nature of folk art as part of the spirit of traditional Chinese art. With this focus, we will not need to worry about its demise because science and art parallel each other in the evolutionary history of human civilization and do not serve as a reference for each other as relative images of progress and backwardness. In this way, folk art and the original culture it represents will transcend the aesthetic dimension of art and acquire new values. If we take traditional literati painting as a reference category, the idea of the Hundred Schools of Thought, which is the basis of literati high art, emerged from agrarian culture and, before it matured, became a part of the culture of “elegance” because the painters held literati status, even though their creators would later also be known as “landlords” or “hermits.” Although their creators were also closely associated with the countryside as “landowners” or “hermits,” literati culture has not been labeled “heritage” even today because changes in social ecology identified these works as elite. This “elitism” has been established for over a thousand years. We do not fear that Chinese literati painting will become a lost tradition to be protected as an endangered “heritage” in the era of scientific advancement because it is still being enthusiastically pursued as an elite aesthetic culture in both academic and civic cultural circles.

Therefore, the important reason for the dilemma we see today in the slow loss of folk art is not that industrialization has changed traditional manual labor methods but that we have long equated the aesthetic nature of these art forms with “backwardness” due to its conceptual and ideological “nonscience.”

In that case, it is only natural that we should understand the need for folk art to survive only in a “vulgar” cultural ecology. Whether it is “kitsch” or “elegant,” art is commonly used as a human emotional appeal, and in replacing the “kitsch” aspect of cultural ecology, we are also depriving the people who live in that world of their access to this mode of emotional appeal. Therefore, preserving folk art as “heritage” is not a wise way to approach the preservation of all forms of folk art.

Symbolism and labeling are not the way to pass on folk culture

The visual forms of folk art discussed in this article have long been referred to as “folk art” and include both the handicraft techniques that create economic value, as mentioned above and those that support spiritual beliefs. The belief dimension of Chinese folk culture contains many elements, which some scholars have summarized as follows: the worship of heaven and earth, celestial images, nature, animals, plants, spirits, gods, ghosts, immortals, and saints [4], etc. However, the concept of “folk art” itself tends to produce a superficial perception of forms, while ignoring the essence and content of the spiritual beliefs and practices contained in these various forms. As a result, a “productive manner” of protection remains only at the level of “symbolic use.”

For example, “Chinese elements” is a term that has been frequently mentioned in recent years in the context of cultural construction and Chinese branding. There has been a proliferation of “symbolic” uses of Chinese national cultural forms, which is the most “effective” result produced under the slogan of national cultural revival. Thus, in the context of “folk art,” some scholars have suggested that the way forwards lies in combining traditional art with modern design to realize its commercial potential and thus bring it into line with today’s social forms of consumption [5]. This productive approach is already commonly used in contemporary design. If this use of folk art and even traditional culture, dissociated from its original connotations, is taken as a contemporary rebirth of folk art, it is a complete erasure of national cultural values.

First, although market value is not the value sought by folk culture, folk productions cannot be separated from the nourishment of the market. Folk art is “the art of visual images created by the Chinese folk masses to meet their own needs in social life,” “it is the art of the producer, not the art of the professional artist [6].” Excessive commercialization will lead folk art to the path of industrialization, thus detaching it from its original cultural vein and losing the unique spiritual and emotional dimensions of folk art itself. Industrialized folk art will be no different from ordinary commodities, where market demand determines the direction of its production and economic efficiency determines the motivation for its creation. This is not only an undesirable direction for the development of folk art but also a problem that we need to correct after the industrialization of culture as a whole. Can the industrialization of culture lead to the revival of civilization and the enhancement of cultural character? Alternatively, if “industrialization” is just a term used to align various practices with modern society, then the question of what kind of industrialization culture should undergo needs to be discussed in depth. What we see today in the industrialization model is more of a “vulgarization” of culture.

Second, symbolic meaning is a superficial level to stop at in the interpretation of folk culture. In modern art and design, it is possible to use some of the formal symbols of national culture, but this cannot be seen as a development of traditional culture and art. We do not consider contemporary “experimental ink and wash” to be a modern form of Chinese literati painting because they are entirely an extension of Western modernist forms in China; not only is there no relationship to the spiritual and cultural lineage of Chinese literati painting but the use of the medium is merely a borrowing of material symbols and certainly has no relationship to traditional “Chineseness” in the aesthetic sense. Similarly, the purely symbolic use of folk art can only be a superficial application in modern art or modern design and is in no way a rebirth of Chinese folk art, let alone a revival of national culture. These tactics are not a renaissance of national culture, nor can they realize “Chinese art” and “Chinese design” in the true sense of the word, thus losing the independence of Chinese culture. The development and innovation of Chinese culture can only be truly achieved through the inheritance of aesthetic character and cognitive philosophy, combined with the spirit of the times.

More importantly, the “symbolization,” “commercialization” and “industrialization” of traditional culture have completely deprived it of the artistic needs of its creative and living communities. It has always been thought that the production methods of industrial technology cannot penetrate into cultural “production.” In fact, we avoid using the word “production” in the cultural sphere. “Production” connotes to hearers the repetition of work and the reproduction of products, whereas the “uniqueness” of artistic creation is the essence of art. Although folk art subject matter and style is strongly passed down, the uniqueness of the work is determined by the differences in handcraft, the emotional expression of daily life, and the presence of pleasure as the motivation for creating it. Therefore, the “symbolization,” “commercialization” and “industrialization” of folk art as a preservation philosophy can only exploit their “decorative” function. This puts the cart before the horse, and what has been lost is an important group artistic tradition and a community spirit of humanism in Chinese culture.

Conclusion

The creation of folk art is a process of internalization of humanistic concepts and humanistic spirit based on the original philosophy of the working masses, as well as a process of indoctrination of ideas about the construction of social order. In ancient China, the original meaning of edification was “to transform the people into good by the teaching of ritual and music, the meaning of which is to enable the people to unconsciously migrate from good to evil and to realize the change of customs [7].” In Chinese folk art, we can often see the philosophy of “teaching with skill.” However, ordinary Chinese workers did not have the right to speak about the “elite culture” of a postclass society, so their identity remained “lower class” and their culture belonged to the “vulgar” category. Their culture is “mundane” and their ideas, which have continued for generations in expressing their original philosophy, are regarded as “backward.” However, as human beings by their cultural nature, these creators also experienced common artistic and emotional needs in life. The speed of development of contemporary society has been further enhanced by information technology, and while it is true that scientific ideas and advanced technology are rapidly changing the old ways of farming, in many countries that are already considered technologically advanced, we also see that their cultural and artistic traditions still retain a “living ecology,” a result of the respect for the culture of different strata of the community. This is the result of respect for the culture of different communities and for the parallel development of science and art.

The objects of intangible cultural heritage that can be more easily protected in a “productive manner” are the “masterpieces” strongly characterized by the use of “skilled” labor. Traditional folk crafts, whose practitioners are clearly professional and whose works are “productive creations” from the outset, are aimed directly at achieving “commercial” success. They have become “intangible cultural heritage” as a direct result of the technical efficiency of industrial production, which is far greater than their traditions of handicraft. These traditions of intangible cultural heritage, such as lacquer painting, ceramics, embroidery, wood carving, printing, dyeing, silk reeling, and paper making, etc., can be “commercialized” by using “primitive craftsmanship” as part of a productive conservation strategy and can be restored in a “workshop” style of production. Through restoring “workshop” production methods, they can achieve a certain cultural, social, and artistic value.

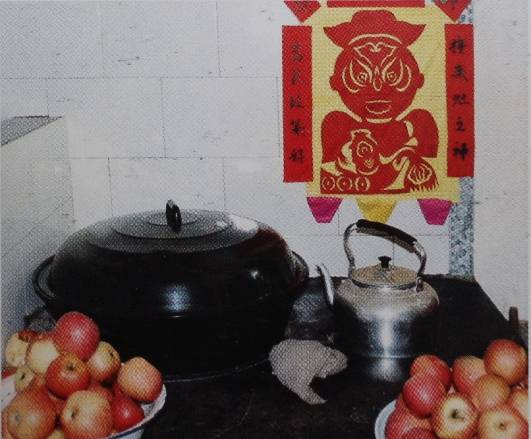

Another part of intangible heritage includes the art forms and customs that emerge from folklore, such as women’s paper-cutting, festive rice-songs (Figure 1), and wedding and funeral rituals, which are based on the daily life of the people and are constructed on folk concepts, customs, and beliefs and emotional appeals (Figure 2, Figure 3). “Once formed, folklore becomes a fundamental force regulating people’s behavior, language and psychology, as well as a way for the population to acquire, pass on and accumulate the fruits of cultural creation [2].”

The folk art formed in the course of daily life was never “productive” or “commercial,” and its fall into the category “heritage” was a direct result of the changing structure of rural life and the fundamental replacement of folk culture. Therefore, when studying the inheritance and development of China’s “intangible cultural heritage” today, we should first distinguish between the situation and nature of these two different cultural relics. In the midst of China’s comprehensive modernization, many folk cultures and arts are in danger of being disconnected from their inheritors and the masses, and it seems that their protection in the context of intangible cultural heritage is the best chance at preservation. Just as the “Department of Folk Art,” once established at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in the 1980s, has become a “Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage” in the new century, this has in fact heralded the demise of folk art. The only place for 'heritage' to end up is in museums, as it is no longer a “living culture.” However, what we need to identify is the skillful behavior within folk art and folk skills that would be eliminated by advances in tools or working methods, such as the production and manufacture of technology for working and living purposes. These skills can indeed be recorded and preserved as heritage by modern means as evidence of the development of human civilization. The roots of their existence are the original spiritual pursuit and aesthetic experience of human beings, as in the case of poetry, calligraphy, and painting, which were the spiritual repositories of the literati and scholars in ancient China. For manual workers who had not received an education in “elegant” culture, the creation of such works was also a form of emotional appeal.

Obviously, the revival of folk art based on living culture should be a “return to the vernacular,” and the only way for folk art to survive is through the continuation and intrinsically driven evolution of vernacular life. However, the decline in the resident population of China's countryside and the “modernization” of living environments and lifestyles have forced us to face the gradual disappearance of vernacular lifestyles, such that a call to “return to the vernacular” is already an unrealistic and empty statement. Therefore, the pursuit of industrialization, marketization, and commercialization is not the way for folk art to survive.

How can traditional folk crafts be protected? Rethinking the “Productive Approach to Safeguarding” Traditional Intangible Cultural Heritage

Introduction

The emergence and development of folk art as a cultural tradition is based on manual labor and the corresponding social ecology of production. The challenge to their survival in contemporary times is due to the differences in the production methods in the age of large-scale industries and information technology. Therefore, today’s emphasis on the preservation of folk art and culture is not only about preserving a form of intangible cultural heritage but also about preserving the foundations that produced a tradition and the ecological conditions that support its growth.

The “productive approach to conservation” is an important conservation strategy. This is a living conservation measure that aims to give new life to folk culture.

The so-called “conservation of productive methods” is an attempt to introduce traditional handicrafts into contemporary social life and the industrial system, so that they can be actively protected in the production activities that create social wealth, without violating the laws of handicraft production and its own way of functioning, and without distorting its natural tendency to evolve [1].

“Conservation in a productive way”

The “productive approach to conservation” aims at the revitalization and sustainable development of China’s intangible cultural heritage and proposes the basic idea of rational use and transformation into productivity. The premise of productive conservation is “not to contradict the laws of handicraft production and not to distort its natural evolution.” The “productive approach to conservation,” if guided by pertinent government departments into a market consciousness, can bring some of China's intangible cultural traditions into a virtuous cycle, maintaining consumption and inheritance. At the same time, “productive conservation” should also be practiced as a form of cultural preservation and innovation. “Traditional handicrafts formed under specific historical and geographical conditions are very different, and different forms of skills have different ecological conditions, value orientations and utilitarian significance [1].”

Abstract

Traditional Chinese folk handicrafts can be divided into productive innovations based on market demand and innovations based on everyday folk life-two basic types with different innovation logics. The study of the succession and development of China’s “intangible cultural heritage” projects should first distinguish the contexts and essential differences between these two types of cultural heritage. This study reflects on the current “productive approach to safeguarding” intangible cultural heritage, pointing out that current projects pursuing cultural conservation and inheritance are often focused on “masterpieces” characterized strongly by “skilled” labor. Safeguarding and transmitting intangible cultural heritage also emphasizes “folk crafts” with a similarly strong “skilled” character. The development and protection of folk art and its industries, however, should be achieved on the premise of respecting its culture of survival.

Funding

This article is the research result of the 2021 Beijing Federation of Literary and Art Circles Basic Theory Research Project, Research on Jin Zhilin's Original Cultural System and Artistic Creation (Project No. BJWLYJB05).

Conflicts of Interest

The author has written the article alone without committing plagiarism.

References

1. Pintian Lv, “Conservation and development in production-Talking about 'productive ways of conservation' of traditional handicrafts,” Folk Art, no.6 (2020): 70-72. [cnki]

2. Jingwen Zhong, Introduction to folklore (Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2010), 3.

3. Liang Zhu, "Human culture becomes: a study on the image generation and iconography of Gao Fenglian's paper-cutting works" (Ph.D. thesis, Central Academy of Fine Arts, 2015), 6.

4. Bing'an Wu, Chinese folk Religion (Shanghai: Shanghai People's Publishing House, 1996), 14.

5. Binjun Mao, "Where is the Road-on the Innovation of Folk Arts," ZHUANGSHI, no. 9 (2006): 34-35. [cnki]

6. Zhilin Jin, Chinese Folk Art (Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, 2004), 7.

7. Gengcui He, "A Textual Research on ‘Educating and Influencing through Ritual and Music’," Modern University Education, no. 4 (2010): 83-86. [cnki]

© 2023 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Liang Zhu, "How can traditional folk crafts be protected? Rethinking the 'Productive Approach to Safeguarding' Traditional Intangible Cultural Heritage." JDSSI 1, no.1 (2023): 28-35.

AMA Style

Liang Zhu. How can traditional folk crafts be protected? Rethinking the “Productive Approach to Safeguarding” Traditional Intangible Cultural Heritage. JDSSI. 2023; 1(1): 28-35.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- "Conservation in a productive way"

- "Backwards" and "advanced"

- Symbolism and labelling are not the way to pass on folk culture

- Conclusion

- Funding

- Conflicts of Interest

- References

by

1 School of Art and Design, Tianjin Tianshi College, Tianjin, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JDSSI. 2023, 1(1), 28-35; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jdssi2023.0606a4

Received: March 10, 2023 | Accepted: May 27, 2023 | Published: June 6, 2023