Inscription Calligraphy and Painting Mutually Influence Each Other

Inscription calligraphy (题跋书法) and painting constitute a text-picture relationship in Ni Zan’s paintings. Inscription calligraphy also plays a role in supplementing and enriching paintings, becoming an indispensable aesthetic factor in paintings. With his inscriptions and paintings under the text-picture perspective, the inscriptions not only accentuate the direction of the paintings in the composition but also fulfill the value of the text. It plays the role of clarifying the principle of the painting and expressing its purpose.

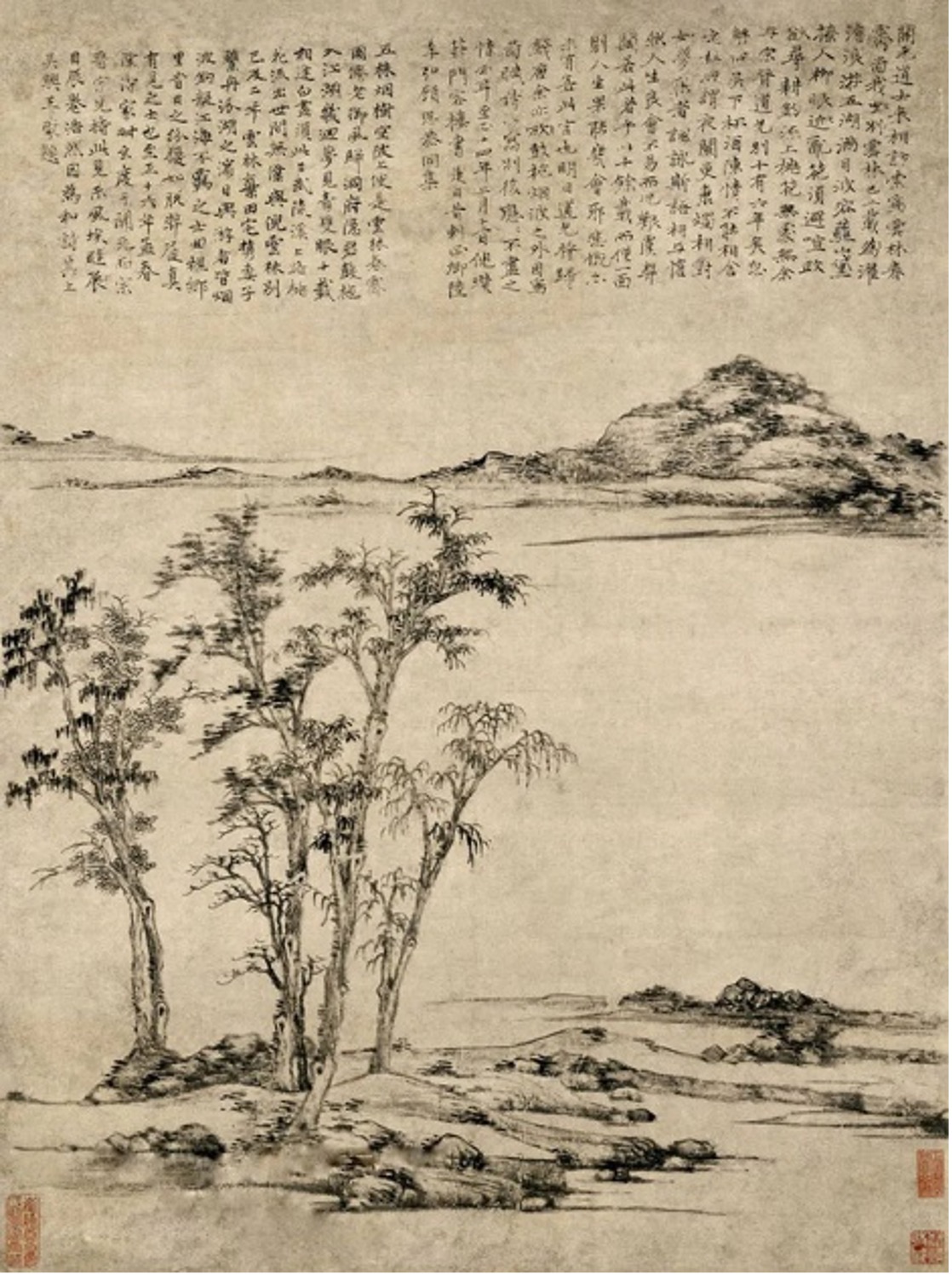

First, calligraphy enhances the aesthetic mood of the painting. Ni Zan typically arranged the style, script, and ink tone of the inscriptions in a way that ensured a harmonious unity with the painting, taking into consideration factors such as the painting’s aesthetic concept, artistic techniques, subject matter, and size. In general, Ni Zan’s overall style of painting is faint and naive, so most of the inscriptions are in lower regular script, with a few occasional cursive scripts. The Landscape of Yushan Mountains and Valleys (Figure 5) shows Ni Zan’s pursuit of a mood of deep seclusion, embodying the aesthetic sense of lightness, purity, elegance, and ease. The painting gives its appreciators an aesthetic sensation like experiencing a “gentle breeze and an old friend,” and the unique flavor of the Jiangnan landscape can be seen from his easy and lively strokes. The six-line inscription at the upper right is as plain and serene as the style of the painting. From the brushwork of lower regular script, the aesthetic spirit in the calligraphy and painting is both subtle and powerful. The strokes begin with a sharp edge, and there is a distinct pause at the end of each stroke. Vertical and horizontal strokes exhibit clear contrast in weight, while diagonal strokes extend to the left and right, incorporating elements of clerical script brushwork. The individual characters have a relaxed and balanced structure, with the strokes forming a closely connected structure. In particular, the two characters “后思” are naturally connected, reflecting Ni Zan’s cheerful mood during his travels. However, Ni Zan chose to inscribe his works in a “lower running script (more cursive than regular)” (小行草), which was more suitable for expressing his feelings. A section of bamboo in Bamboo Branches (Figure 6) is painted with free strokes, horizontal and vertical, without regard to craftsmanship and is intended to express the artist’s carefree energy. As a result, the brushwork, rhythm, breath, and posture of his calligraphy are well integrated with the poems and images, and the aura of calligraphy overflows the ink and paper [29]. From this, it can be seen that Ni Zan usually regarded inscriptions as complementing and harmonizing the image. This method is used to achieve a new aesthetic harmony, combining painting and calligraphy with reality and abstraction.

Second, calligraphy illuminates the theory of painting. As one scholar said, “Calligraphy, a unique Chinese art, is the backbone of Chinese painting. To write poems on a painting, one uses calligraphy to illuminate the brushwork in the painting, and the poems to set the mood of the painting [30].” This statement is fully reflected in Ni Zan’s paintings. Inscription calligraphy, using poetry as a carrier, can make up for the lack of a painting’s expressive ability and help to express the painting’s context. As Qing Dynasty artist Fang Xun said, “When the painting is insufficient, express it through the inscription [31].” Ni Zan was good at painting with the principles of Zen and Taoism, advocating the aesthetic requirement of simplicity, and he was especially good at painting in freehand. The orchids and bamboo in his paintings are often scribbled with a few brushstrokes and are not even recognizable. The pictorial language in his paintings is weak, and he needs to use poems to convey his personal intent. Whenever a simple and meaningful painting fails to obtain the self-sufficiency of a realistic image, the inscription calligraphy in the painting plays the role of interpreting and indicating the title. In view of this, Ni Zan’s “calligraphic techniques in painting” became his main means of representing, expressing, and creating an atmosphere.

http://wenhui.whb.cn/zhuzhan/bihui/20210128/390108.html)

The Relationship between the Writing Approach and the Carefree Style

As seen from the preceding “expression of the carefree style” (写胸中逸气), Ni Zan’s definition of carefree was a natural and simple expression of ink and brushwork. He believed that there was no need to be demanding of finesse and deliberateness or to stick to conventional methods but rather to pursue the joy of expression. Instead of Chinese realistic painting, he advocated freehand painting in a manner characterized by lightness and elegance, emphasizing the expression of emotion. The “carefree” style of his paintings has a strong sense of calligraphy and lyrical character. In his Reply to the Letter of Zhang Zaozhong, he said, “What I think of as painting is just sketching and scribbling, not striving for realism, but just drawing for self-entertainment [32].” From this point of view, the “carefree pen” (逸笔) and the “expression of carefree energy” are representative of the painting and the human character, respectively, corresponding to the facsimile and lyricism of painting. The two are unified through the “writing” approach, and the ideographic function of calligraphy plays a key role in their transformation.

In Ni Zan’s view, “writing” is the same as “conveying one’s sentiments” (寄兴). That is, for the purpose of self-indulgence, he expects artist to disregard the rules and rashly draw from the heart an image that will express emotional thoughts. He said, “The drawings are just for leisurely expression, without being bound to image or sound [33].” In other places, he said, “Unfolding the scroll to imagine the secluded landscape, he wanted to record the mood of the moment [34].” He added, “The mind thinks distantly of soaring cranes and sets its thoughts on the clouds of the mountain ranges [35].” These poems show that Ni Zan’s paintings have an artistic tendency to emphasize subjective consciousness. He knew that painting and calligraphy were aesthetically the same and that painting was like calligraphy, a creative and intentional practice. By using the rules of the ancients to mold natural objects into images with subjective ideas, Ni Zan put the focus on writing one’s own feelings. The opportunity enclosed by this manner of “conveying one’s sentiments” lies in the mutual sensation between the heart and the object, and the resulting painting is a random touch without rational thinking that is instantaneous and accidental. Ni Zan emphasized the meaning of “writing” in his paintings, reflecting the fact that he paid particular attention to the free expression of his emotions. He handled the pen and ink with a playful attitude and was spontaneous. The easy and unrestrained strokes of the brush freely painted the imagery in his mind and were extremely personalized.

While expressing his emotions through painting, Ni Zan also frequently emphasized the swiftness and continuity of brushwork. This greatly diminished the impediment that the meticulous, realistic depiction of objects could pose to the artist’s emotional expression. He repeatedly mentioned the unrestrained means of painting in his inscriptions. The term “unrestraint” (纵横) has a strong ink-play connotation. In this way, Ni Zan could break free from the constraints of previous artistic conventions and attempt to reveal his aspirations through continuous brushwork. It can be said that unrestraint is the best way he found for dealing with form and spirit or priority and reason. He painted without pretense of rational thought, expressing his innermost feelings in an unrestrained manner. In the process of painting, Ni Zan accomplished the transition from using a carefree style of painting to expressing a carefree nature of human character. Shi Tao of the Qing Dynasty described Ni Zan’s way of writing painting in this unrestrained manner as follows, “Ni Zan’s paintings depicting waves, sand, and streams were spontaneous and natural, revealing an ethereal and refreshing aura that evoked a sense of calm. However, those who came later only mechanically imitated his withered simplicity, which is why these paintings lost their divinity [36].” From this perspective, he believed that Ni Zan, in the flow of his brushwork, guided by his circumstances and prioritizing the expression of his inner thoughts, could conjure up landscapes that harmonized perfectly with his own soul. In other words, the brush and ink did not passively shape the landscape, but rather, the changes in brushwork triggered changes within the landscape itself. Ni Zan’s ink bamboo paintings, much like cursive script, freely expressed themselves, manifesting the spirit of ink bamboo through expressive brushwork.

It should be made clear that in Ni Zan’s time, even though the concept of “writing” was already deeply rooted in people’s minds, painting could not in any way be limited to depicting only one side of an object. Tong Shuye explained it brilliantly, “While Song painting does not advocate faithful sketching or being bound by objective reality, what it does depicts is only a nature that has been imbued with human emotions. Although Yuan paintings do not completely abandon objective realism, what they depict is mostly the expression of personal freedom through nature [37].” Indeed, the reason why the Yuan paintings emphasized “writing” was to break away from only realist resemblances to pursue the “resemblance and unlikeness” of painting. Therefore, Ni Zan said, “Bamboo painting should never be so delicate that it has the style of a craftsman. I once painted bamboo, and those who looked at it asked me what kind of tree it was. I smiled and continued painting, which is beyond words [38].”

In addition, Ni Zan directly linked “writing” painting to the artist’s character. There are numerous works on the history of painting that attest to Ni Zan’s noble character. For example, Bu Yantu said in Questions and Answers on Painting Principles, “Ni Zan’s works are devoid of overlapping mountains and dense forests. Rather, it is an ethereal landscape of ice trails, with only a splash of water and remnants of mountains. There are not any signs of human activity but enough [is depicted] to be a masterpiece of his generation [39].” It is precisely because Ni Zan has a noble character that he is able to create an ethereal state of absolute splendor. Similarly, Ni Zan wrote in Inscription on Ke Jingzhong’s Bamboo, “He who can write bamboo with perfect skill is perhaps only Zhao Gao or Su Shi. If the brush and ink want to convey a pure character, it needs to be written in seal script [40].” In this sentence, Ni Zan clearly expressed that literati painting is the physical form of the artist’s qualities. Regarding carefree work (逸品), Yu Jianhua’s explanation can help us understand it better. He said, “Ni Zan had a high moral character, excelled in literature and poetry, and was superbly skilled in calligraphy. Although his work was not particularly refined, it exuded an aura of elegance. It is as if the paintings were created by literati, full of bookishness, but without the deliberate pursuit of complexity and worldly flavor. Most of his works are of this type. Initially, critics of painting regarded super work (神品), fine work (妙品), and skillful work (能品) as the main criteria, while carefree work was regarded as a minor criterion. Later, it was considered that carefree work was above all else and ranked first [41].” Importantly, “the Yuan dynasty filtered calligraphic concepts into painting but apparently with great restraint. They did not overemphasize the calligraphic nature of the brush and ink, nor did they advocate the use of calligraphy as a substitute for painting. In contrast, they emphasized the similarity in method between calligraphy and painting brushwork and combined it with their own personalities to create supreme painting achievements [42].” It can be seen that for literati paintings to be honored as carefree work, the first requirement is to have noble character, and the second requirement is to be good at both poetry and calligraphy. The relationship between noble character and poetry and calligraphy is one of internal and external compatibility. Moreover, poetry and calligraphy are both expressed in the form of “writing,” so painting also borrows “writing” to express the noble character of the painter. Ni Zan “wrote” paintings for his own amusement, and in the history of painting, his work was praised by later generations as typical of carefree work. This is because he was not only a man of high character but also good at poetry, calligraphy and painting and able to integrate and switch styles freely. In general, “writing” is not only the way Ni Zan accomplished a “carefree” spirit in poetry, calligraphy, painting and other arts but also a true reflection of his own high and elegant character.

While Ni Zan brought literati painting to its peak at the end of the Yuan Dynasty with his specialized brush and ink techniques, he also carried forward the artistic concepts of ink play (墨戏) and “calligraphic techniques in painting” that had been practiced since the Tang and Song dynasties. His elegant and simple literati paintings emphasize both realism and freehand expression. Painting is neither a pure display of skill nor a simple expression of literati interest but rather the pursuit of expressing one’s plain and natural state of mind with brushes and ink. The expression of painting and the principle of the mind form a cross relationship.

Additionally, imagery became the medium through which Ni Zan’s paintings achieved “a painting method that replaces craftsmanship and meticulousness with the writing method (以写代工)” and “calligraphic techniques in painting.” The Tang Dynasty calligraphy theorist Zhang Huaiguan summarized the internal mechanism of creating calligraphic imagery as “containing a multitude of different things and being polished into a common image [16].” According to Zhang Huaiguan, calligraphic imagery represents natural objects with a high degree of generalization. Because the calligrapher participates in the activity of taking images and capturing the essence with intention, the calligraphic imagery is also a unity of the scene, the mind and the object. It is a combination of the imagery of nature and the intention of the calligrapher, which carries the specific artistic personality and aesthetic interest of different calligraphers. Similarly, both calligraphy and painting are symbols of the mediums used by artists to express their ideas and sentiments. Ni Zan in Zhan Yun Xuan’s epigraph said, “Sorrow and joy both arise from delusion. To attain unity with nature, one must maintain inner tranquility and understand the essence of emptiness, remaining unaffected by external changes [17].” This sentence indicates that painting is not to focus only on the form of the object but to go deeper and grasp the inner spirit and posture of all things. Painting and nature are no longer bound by a relationship of tracing and reproducing, as an intermediate link emerges of “likeness and unlikeness.” When Ni Zan painted, he employed free and daubing brushwork, emphasizing the significance of “writing.” Calligraphy’s representational function allowed him to create a pictorial language based on line art. As a result, the pen-and-ink lines in Ni Zan’s literati paintings no longer served the function of depicting outlines but rather adopted an aesthetic connotation of freehand calligraphy. This was a manifestation of his self-conscious search for an external intervention to renew the discipline of painting.

Finally, Ni Zan’s paintings and calligraphy are based on the highest standards of expressing light and natural interest, which are the two expressive forms of his aesthetic concept of tranquility and relaxation. This prompted his calligraphy and painting to break through their limitations and achieve fusion at a transcendent spiritual level, reflecting a highly unified aesthetic. This common aesthetic is in his sparse and simple calligraphy and his desolate and lonely paintings. This is particularly evident in the calligraphy of his inscriptions. Inscriptions on the painting use the poem as a carrier of meaning; poetry and painting are the same, naturally interpreted as poetry, calligraphy and painting as a whole. However, the pursuit of the spirit of tranquility and relaxation is the fundamental reason for the unification of the art of calligraphy and painting. Ni Zan commented that Zhang Waishi (张外史) did not care about the delicacy or clumsiness of his artwork and that his paintings had a clear and elegant flavor: “Calligraphy and painting, no matter how high or low the craftsmanship is, why should one purposefully pursue a famous reputation like Yan Zhenqing or Mi Fu. When you look at those historical works depicting strange stones, the brushwork seems to be just like Mi Fu’s calligraphy, revealing a sense of intoxication [18].” This statement has three meanings: First, calligraphy and painting transcend their own limitations and have an intrinsic aesthetic homogeneity—regardless of craftsmanship. Second, “writing” indicates that Zhang Waishi is free from the constraints of realism, and his painting style is loose and free, emphasizing emotional expression. Third, the fusion of painting and calligraphy has contributed to the progression of literati painting from the visual to the spiritual aesthetic level. Ni Zan’s inscription was intended to praise Zhang Waishi, but it is more like he was declaring his own aesthetic ideal for art creation. Ni Zan’s artworks embody a certain common aesthetic of being “carefree” (逸), and this commonality permeates and plays a role in his painting and calligraphy creations. From this, it can be seen that his calligraphy and painting transcend an external correlation with expression and possess a consistency of inner aesthetic character. It is this consistency that provides the rational basis for applying calligraphy to paint, and calligraphy and painting have become the traces of his consciousness of all things and inner experience. Therefore, the artist’s noble spirit is contained in elegant and graceful brushwork.

by Xiaofei Pang *

School of Design, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2023, 1(1), 15-32; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2023.0926a2

Received: August 1, 2023 | Accepted: September 10, 2023 | Published: September 26, 2023

Introduction

“Calligraphic techniques in painting” is a common theme when studying the history of traditional Chinese painting and calligraphy; its theoretical origin is very deep in the history of the development of aesthetic thought for painting and calligraphy. During the Tang Dynasty, Zhang Yanyuan proposed the concepts of “a common origin for Chinese painting and calligraphy” and “a common essence for Chinese painting and calligraphy” in Notes of Past Famous Paintings. These concepts were further developed by Song Dynasty scholars such as Guo Xi and Han Zhuo. Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan Dynasty established these concepts as the aesthetic norm with “calligraphic techniques in painting.” Subsequently, the artistic concepts of a “mutual relationship between calligraphy and painting” (书画相通) and “applying calligraphic techniques in painting” (援书入画) gained widespread recognition. The literati painters of the Yuan Dynasty not only promoted “calligraphic techniques in painting” in theory but also strengthened the calligraphic awareness of “writing” painting in creative practice, which is especially reflected in Ni Zan’s painting theories, painting postscripts and artworks. Ni Zan is a representative figure of the recluse painters of the Yuan Dynasty. The aesthetic meaning of “writing” in his paintings is not only a presentation of his pen-and-ink style but also a sign of his insistence on the noble character of the literati. In summary, to better interpret the aesthetic value of Ni Zan’s “writing” in his paintings, this paper intends to discuss four aspects: the theoretical origins of his “writing” painting, the inevitability of “writing” painting, the expressiveness of “writing” painting, and the relationship between “writing” painting and “carefree style” (逸气).

Theoretical Origins of "Writing" Painting

TNi Zan’s theory of “writing” painting is centralized in the poem he composed for the painting Bamboo: “The bamboo I paint is just to express the carefree energy in my heart. How can I care about the similarity [to other works], the density of the leaves or the curvature of the branches? If painters do not follow the [standard] method when drawing bamboo and [instead] apply a casual approach, viewers will think it’s just some reeds and cannot firmly identify it as bamboo. It is truly hard to satisfy the viewer [1]!” Ni Zan described “painting bamboo” as “writing bamboo.” Therefore, “writing” not only encompasses the meaning of painting but also emphasizes “calligraphic techniques in painting;” the latter also means that painters give attention to the lyrical character. The relationship between “writing” and lyricism will be discussed in detail in Part Four. The theoretical origins and development of Ni Zan’s “writing” (写) approach to painting will be summarized first.

Ni Zan’s “writing” approach to painting is based on the theory of “a common origin for Chinese painting and calligraphy” and “a common method for Chinese painting and calligraphy” in Chinese art history. Zhang Yanyuan of the Tang Dynasty first theorized the concept that “painting and calligraphy are of a common origin”, and he also said in Notes of Past Famous Paintings, “Calligraphy and painting are the same form of artistic expression without clear distinction. Because there was no medium to express meaning clearly, words were invented. There was no way to show the image of things, so painting was created. Therefore, although calligraphy and painting have different names, they have a similar essence [2].” In Zhang Yanyuan’s view, calligraphy and painting were indistinguishable from each other at the beginning of their existence, both originating from the imitation and simulation of nature. Moreover, the glyphs in calligraphy are similar to paintings that express the shape of objects, so calligraphy and painting are of the same origin. After Zhang Yanyuan found the basis for the theory of a common origin for Chinese painting and calligraphy,” he deeply analyzed the creative techniques of calligraphy and painting and concluded that the two had much in common. He also mentioned in Notes of Past Famous Paintings: On the Brushwork of Gu, Lu, Zhang, and Wu that “in the past, Zhang Zhi studied the cursive techniques of Cui Ai and Du Du, and changed them to form today’s cursive style, which is accomplished in a single stroke with a smooth spirit and no breaks between lines. Only Wang Xianzhi deeply understood this method of expression, so the beginning of his calligraphy often continued from the previous line, which was called one stroke of calligraphy by the world. Later, Lu Tanwei also created a brush painting technique with continuous strokes. It can be seen that both calligraphy and painting utilize the same brushwork [3].” Zhang Yanyuan cited Wang Xianzhi’s one-stroke calligraphy (一笔书) and Lu Tanwei’s one-stroke painting (一笔画) as two cases in the history of art that illustrate a point: both calligraphy and painting pursue the aesthetic of the spiritual dimension, and the means of realizing such spiritual aesthetics is brushwork. It can be seen that Zhang Yanyuan interpreted and thought about “a common method for Chinese painting and calligraphy” on the basis of summarizing the practice of his predecessors and finally analyzed the reasons and origins of “a common method for Chinese painting and calligraphy.” In this way, Zhang Yanyuan’s theory of “a common origin for Chinese painting and calligraphy” transitioned cleanly to an articulation of “a common method for Chinese painting and calligraphy,” which is easier to understand and was accepted by later generations [4].

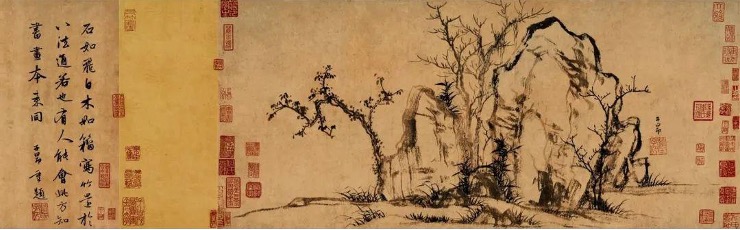

Since the Tang Dynasty, Zhang Yanyuan’s concepts of “a common origin for Chinese painting and calligraphy” and “a common method for Chinese painting and calligraphy” have never ceased to have an impact on the history of painting and calligraphy. Guo Xi of the Northern Song Dynasty and Zhao Mengfu of the Yuan Dynasty expressed similar artistic views in their writings [5]. For example, Zhao Mengfu’s poem inscribed on Painting Scroll of Scenic Rocks and Sparse Woods (Figure 1) says, “To draw stones, one should use the ‘flying white’ (飞白) strokes in calligraphy, and to draw trees, one should use the ‘large seal script’ (籀书,即大篆字体) strokes in calligraphy. However, when painting bamboo, one should be proficient in all eight methods. If someone can master this art, they should understand that calligraphy and painting are fundamentally the same [6].” In his poetry, he explicitly presented the theory of “calligraphic techniques in painting,” asserting that the brushwork for rocks, trees and bamboo in painting corresponded to or shared similarities with the “flying white” approach (飞白), “large seal script” (籀书), and the “eight rules of writing ‘Yong’ in Chinese” (永字八法) in calligraphy. He even articulated the idea that directly using calligraphic brushwork to depict objects still represented the interconnectedness of calligraphy and painting in terms of brushwork. However, Zhao Mengfu, as a high-ranking minister, was especially cautious in his actions in a dynasty ruled by foreign conquerors. This restrained approach led to the fact that he could never forget his own status while engaging in creative painting endeavors. Therefore, he could not fully achieve the true essence of “calligraphic techniques in painting [7].” From his existing paintings, it is obvious that he did not use “writing” as his dominant form of expression. In Zhao Mengfu’s paintings, the modeling of objects is complete and accurate, and the brushwork of cunran (皴染) is refined and meticulous. In addition, he advocated the use of a traditional aesthetic in his paintings and inherited more of the traditional pen-and-ink language of the Tang and Song dynasties, which emphasized realism in the depiction of physical objects [8]. Although the theory of “calligraphic techniques in painting” was first proposed by Zhao Mengfu, it was not thoroughly implemented in his creative practice. In contrast, his artistic concept was fully inherited and developed by Ni Zan, a recluse painter (隐逸画家) of the Yuan dynasty.

Abstract

The way of “writing” (写) is one of the characteristics of pen-and-ink expression in Chinese literati painting, which is prominently embodied in the aesthetic ideology and the paintings of the Yuan dynasty painter Ni Zan. Ni Zan’s principle and practice of “writing” painting is rooted both in his inheritance of the pen-and-ink traditions of the Song and Yuan literati painters and in the following concepts in the history of painting: “a common origin for Chinese painting and calligraphy,” (书画同源), “a common essence for Chinese painting and calligraphy,” (书画同体) and “a common method for Chinese painting and calligraphy” (书画同法). In Ni Zan’s paintings, he used calligraphic brushwork to capture the romantic charm of the objects, which was a free expression of his true feelings and a means of self-entertainment. At the same time, his painting and calligraphy were influenced by the social trend emphasizing the “integration of literature and art” (文艺相融) in the Yuan Dynasty, resulting in a high degree of internal consistency among pen-and-ink performance, creative approaches and aesthetic style. Consequently, there was a certain degree of inevitability to the introduction of a “writing” style into his paintings. Ni Zan’s calligraphy and painting are intertwined and integrated, presenting the visual characteristics of the same brushwork. The principle of blank space is similar in both calligraphy and painting, and the same common principles apply to ink intensity and a carefree style. More importantly, “writing” (写) in his paintings, as a way of conveying the language of Ni Zan’s pen-and-ink style, also embodies the character of high elegance, which made the pursuit of a written mood in pen-and-ink paintings a common goal of literati paintings throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Funding

This research was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Foundation of China: Theoretical and Practical Research on Chinese Aesthetics and Art Spirit. (16ZD02)

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

References

1. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 302.

2. Zhang Yanyuan, Notes of Past Famous Paintings (Shanghai: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 1964), 3.

3. Zhang Yanyuan, Notes of Past Famous Paintings (Shanghai: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 1964), 34.

4. Sinologist Laurence Sickman stated that “In Tang Dynasty art, there was a conscious phenomenon of combining calligraphy with painting. We should understand that this is an attempt by painters to achieve expressiveness through brushwork. Brushwork requires both the necessary and expressive lines to convey the spirit, thus presenting real forms with rhythmic beauty. Calligraphers write beautifully because they possess the brushwork skills that any painter would envy.” Quoted from Bao Huashi, “Chinese Style for Western Use: Roger Fry and the Cultural Politics of Modernism,” Literature and Art Studies, no.4 (2007):141-144. [cnki]

5. Guo Xi stated that “Some people say that Wang Youjun enjoyed observing geese, but in fact, he was expressing his interest in how calligraphers use their wrist movements skillfully to write characters. This aligns with discussions about the use of brush and ink in painting.” Quoted from Yu Jianhua, Classified Compilation of Ancient Chinese Painting Theories (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2000), 634.

6. Peng Lai, Ancient Painting Theory (Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 2009), 210.

7. The concept of "Calligraphic Techniques into Painting" implies expressing the rich emotions of the painter during the painting process. However, as a high-ranking official, Zhao Mengfu had to exercise caution in his words and actions and may not have fully revealed his thoughts in his paintings.

8. Zhao Mengfu’s so-called paintings with ancient meanings mostly refer to the connotations in Tang paintings.

9. Ni Zan’s paintings are characterized by simplicity and lightness, with single objects and spaciousness. This gives the image the powerful expressive power of seeing the big in the small and the complex in the simple.

10. Ming and Qing painters especially like Ni Zan paintings, hanging at home to show their own elegance, and even to the point of “every family has Ni Zan’s Paintings.”

11. Around 1328, Ni Zan’s elder brother and mother died, leaving him in charge of family affairs. Therefore, Ni Zan’s life changed. However, Ni Zan was not good at managing money, and he made extensive gardens and did not engage in production, so his family’s fortunes declined. Quoted from: Lu Hongdi, “Ni Zan’s Landscape Art,” Art Market, no.7 (2009): 82. [cnki]

12. On the one hand, he used ink and bamboo as a vehicle for expressing his thoughts, and on the other hand, his ink and bamboo drawings also reflect the new direction of literati painting in the Yuan Dynasty from realistic painting to freehand.

13. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 112.

14. Zhu Zhongyue, The Chronicle of Ni Zan’s Artworks (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 1991), 66.

15. Gao Jianping, “The Different Ideas Between the Chinese and the Europeans on the Relationship Between Handwriting and Painting,” Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences), no.1 (2018):147. [cnki]

16. Pan Yungao, Zhang Huaiguan’s Book Theory (Changsha: Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, 1997), 25.

17. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 30.

18. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 255.

19. The research method of “text-picture” refers to the exploration of the expressive character of “writing” in Ni Zan’s paintings through the comparison and reference between the text and the picture.

20. Dong Qichang, Essays on Painting Zen Studio (Jinan: Shandong Pictorial Publishing House, 2007), 16-17.

21. Yu Feng, In Other Words, trans. Wang Hui (Beijing: Rong Bao Zhai Publishing House, 2012), 140.

22. Li Rihua, Wei Shui Xuan Diary (Shanghai: Shanghai Far East Publishers, 1996), 418.

23. Peng Jixiang, “Dance: The Music and Dance Spirit of Traditional Chinese Art - The Art of Lines,” Art Panorama, no.6 (2017): 49. [cnki]

24. Wen Zhaotong, Research Materials of Ni Zan (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 1991), 3.

25. Zong Baihua, Aesthetic Stroll (Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1981), 138.

26. Dong Qichang, Essays on Painting Zen Studio (Jinan: Shandong Pictorial Publishing House, 2007), 101.

27. Yu Jianhua, Compilation of Ancient Chinese Painting Theory (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2000), 934.

28. Zhang Chou, Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Chinese Painting and Calligraphy Volume 4 (Shanghai: Shanghai Calligraphy and Painting Publishing House, 1992), 352.

29. Pang Xiaofei, “Research on the Aesthetic Value of Ni Zan’s Inscriptions on Painting from the Image – Text Perspective,” Ethnic Art Studies, no.6 (2016):196-197. [cnki]

30. Zong Baihua, Aesthetics and Artistic Conception (Beijing: People’s Publishing House, 1987), 151.

31. Yu Jianhua, Compilation of Ancient Chinese Painting Theory (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2000), 241.

32. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 319.

33. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 46.

34. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 69.

35. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 73.

36. Shi Tao, Discourse on Landscape of Shi Tao (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2006), 102.

37. Tong Shuye, Tong Shuye’s Theory of Painting (Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House, 1999), 207.

38. Ni Zan, Painting Manual: New Branches, Withered Bamboo in the Rain.

39. Bu Yantu, Questions and Answers on the Art of Painting (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2007), 650.

40. Ni Zan, Collection of Qingbi Pavilion (Hangzhou: Xiling Seal Engraver’s Press, 2010), 118.

41. Yu Jianhua, Chinese Painting Research (Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, 2000), 34.

42. Shen Gang, “Advantages and Disadvantages of Calligraphy into Scholars’ Paintings,” Journal of Shanghai Teachers University (Social Sciences), no.7 (2002):73. [cnki]

© 2023 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Pang Xiaofei, "Calligraphic Techniques in Painting: The Aesthetic Expression and Literary Significance of “Writing” in Ni Zan’s Paintings." JACAC 1, no.1 (2023): 15-32.

AMA Style

Pang Xiaofei. Calligraphic Techniques in Painting: The Aesthetic Expression and Literary Significance of “Writing” in Ni Zan’s Paintings. JACAC. 2023; 1(1): 15-32.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Theoretical Origins of "Writing" Painting

- The Inevitability of “Writing” Painting

- The Expression of “Writing” Painting

- The Relationship between the Writing Approach and the Carefree Style

- Conclusion

- Funding

- Conflicts of Interest

- References

Ni Zan was not concerned with the precise portrayal of bamboo in his painting. Instead, he emphasized the expression of his emotions and sentiments. He was unhesitant even if viewers were unaware of his depiction. It is precisely because he emphasized the significance of the spirit of art as a core value in the artwork that he highlighted the creative method and aesthetic connotations of "writing". Although some painters before Ni Zan had already given attention to the use of calligraphic brushwork, they either spontaneously tried to use this brushwork in their paintings or explicitly put forward the theory of “calligraphic techniques in painting.” However, none of them effectively combined theory and practice. Under the influence of Zhao Mengfu, Ni Zan consciously imbued his paintings with calligraphic brushwork. He also emphasized the spiritual integration of calligraphy and painting, ensuring that the emotions of the artist were freely expressed during the painting process. Ni Zan’s concept of “writing” painting not only changed the tradition of pen-and-ink drawing from a focus on modeling but also shifted people’s attention from imitating objects to appreciating brushwork and the artistic mood. At the same time, it also highlighted the expressive function of painting compared with previous artists [9].

From a theoretical perspective, it is evident that Ni Zan’s theory of “writing” painting did not emerge out of thin air but rather went through an extensive and gradual development process. It is rooted in the traditional Chinese art theories of “a common origin for painting and calligraphy” and “a common method for painting and calligraphy.” Through the inheritance and interpretation by Song dynasty painters and then the explicit refinement of “calligraphic techniques in painting” by Zhao Mengfu in the Yuan dynasty, this aesthetics were ultimately fully developed by Ni Zan. On the basis of inheriting ideas from his predecessors, he gradually developed this aesthetics by integrating his own creative experience and artistic insights. This process reflected the developmental pattern of Chinese literati painting, which progressed from painting to realistic depiction and then to “writing.” It also represented the path from mimetic representation to expressive and heartful meaning. Ni Zan’s emancipatory approach to painting, which infused artwork with a pure and effortlessly natural sense, had a profound impact on the creation and aesthetics of the painting world through the Ming and Qing dynasties [10].

The Mutual Influence of Calligraphy and Painting

Using the Same Brushwork

Ni Zan’s borrowing of calligraphic brushwork in his paintings is comprehensively expanded and deepened, emphasizing the priority of calligraphic brushwork. This is evidenced in later painting theories. For example, Dong Qichang in the Essays from the Zen Painting Studio said, “Depictions of cloud forests require angled brushstrokes with proper strength, and rounded strokes should not be used. The wonderful thing is the smoothness and uprightness of the brushwork [20].” Wang Hui commented on Ni Zan’s Painting of Bamboo, Stone, and Frost-Covered Branches, “In this painting by Ni Zan, the bamboo is depicted as if in regular script, the stones as if in running script, and the trees as if in cursive script. This atmosphere of purity and solitude is expressed through the pen and ink, making him unique among the four representative painters of landscape painting in the Yuan Dynasty [21].” Li Rihua remarked on Ni Zan’s Painting of Bamboo, Stone, and Lofty Branches (Figure 4), “His brush is used boldly and powerfully, and the details on the tree trunks are carved with dry strokes, which are dotted with a few awns. The lines of the stones are like the etched cutting in a seal, while the bamboo leaves are simple and powerful, a rarity in Ni Zan’s painting style [22].” Taking Ni Zan’s Ink Bamboo Painting as an example, this artwork can be described as a seamless and continuous creation. From the trend, density and overall layout of the bamboo branches, the painting has reached a point where he is at ease with his feelings, presenting the aesthetic characteristics of the ink bamboo, which is simple, thin and straight. The artist uses a mixture of seal script and cursive brushwork to create a bamboo pole that rises up from the ground with a meticulous and strong middle stroke. The bamboo leaves are drawn with a sharp side stroke, swaying in the wind. Ni Zan’s brushwork is strong, his lines are refined, and his compositions are simple and clear, creating a pen-and-ink effect that “the brush is finished, but the momentum is not yet finished.” This is just as expressed by Peng Jixiang, “In Chinese painting, introducing cursive script into the painting means representing static volume as time to the utmost... Space is extended to the maximum as the flowing trajectory of time [23].” In addition, Ni Zan’s paintings are mostly of mountains and lakes, but after he incorporated the abstracted and condensed calligraphic freehand, he achieved a unique world of landscapes in his paintings. As dots in calligraphy were the most convenient form of freehand for him, Ni Zan often used the moss-dotting technique (苔点法) in his paintings. He said, “There is no need to outline the form of the vines on the tree in detail, just highlight the key points and the viewer will naturally feel the presence of the vines. If the vines are painted too deliberately, they will carry a style of tacky craftsmanship [24].” He transformed the vines into dots, and the use of dots drove the abstraction and simplification of the vines into an indicative pictorial symbol.

The Same Principle of Blank Space

In The Sense of Space Expressed in Chinese and Western Painting Techniques, Zong Baihua discusses how spatial awareness in Chinese painting is rooted in the spatial expressiveness of calligraphy. Therefore, it can still be regarded as an abstract expression of pen and ink [25]. Ni Zan used the structure of specific Chinese characters to summarize objects so that his pictorial iconography gradually became consistent with calligraphy. The glyphic structure of calligraphy represents a high degree of the condensation and generalization of natural objects. Because of its objectivity, this aesthetic permeates and influences the layout and structure of the painting. By borrowing from the structure of calligraphy, Ni Zan ingeniously made the layout of his paintings infinitely more conceivable than a realist depiction. Ni Zan’s excessive attention to brushwork and ink in his paintings inevitably led to the neglect of objects and the formation of simple compositional patterns. This compositional pattern is relatively single and stable, such as a pavilion and bamboo, which are abstracted to form a structure similar to ideograms. When he conceived the idea of painting, he would first envision the composition of the Chinese characters and choose a complete image that suits the meaning of the theme. He then moved these ideas and combined them with reference to nature. At this point, the “management position” acquired an independent aesthetic merit in Ni Zan’s paintings.

The Same Method of Using Ink Intensity

Ni Zan’s “light ink” in painting and calligraphy has been discussed by many earlier scholars. For example, Dong Qichang said, “He insists on using one type of light ink, which I think is hard to imitate [26].” Qian Du said, “Ni Zan spares ink like gold. His brush is light and loose, with more dry strokes and fewer moist strokes, more chapped than rendered [27].” Zhang Chou said, “Ni Zan’s calligraphy was originally very powerful, but later his brushwork gradually became light and elegant. His paintings were very detailed at first and then gradually tended to become simple. Some people only see his later works and fail to appreciate his exquisite skills in his youth, which is truly a pity [28].” Ni Zan’s use of color focuses on the changes in spatial depth over time on the basis of presenting the original color of the object. For example, in those landscape paintings expressed in ink, the dead wood, rocks, and sloping banks are all rendered in pale ink marks. The color tone and brushwork are integrated with the objects, pursuing the dynamic changes of the objects in time and space. Similar to the up-and-down connection of the strokes in lower regular script, this approach constructs an atmosphere of dispersion and bleakness.

The Same Carefree Style

The carefree style is the intrinsic reason why Ni Zan’s painting realized “calligraphic techniques in painting”, and it was also the expressive feature that conveyed the meaning of writing. Ni Zan put the “carefree energy of life” into practice with the movement of pen and ink, and his brush followed his feelings and expressed his thoughts fluently. His brushwork is exquisite, combining the elegance of lower regular script as well as the ups and downs of running script and skilled and unmodified cursive script. The lines in the painting are no longer constrained by the precise depiction of objects but rather express the vitality of their life spirit with the rhythm of ancient brushwork. Incorporating various calligraphic techniques, such as dotting, hatching, or sweeping the brush horizontally, Ni Zan assigned shapes based on the objects, reflecting a sincere and tranquil aesthetic unity.

Conclusion

Ni Zan is good at placing painting, poetry and calligraphy in the same expressive space. Poetry, calligraphy, and painting blend seamlessly with each other, forming an elegant, tranquil, and simple aesthetic style. First, the calligraphy of the inscription in the painting is both poetry and calligraphy, inscribing the poem in lower regular script or cursive script in the painting. Furthermore, the calligraphy of the inscriptions harmonizes with the imagery, creating a seamless “text-image” relationship. The objects in the painting are depicted with almost calligraphic brushwork and ink, and the calligraphy and the painting match perfectly in terms of brushwork, ink color and spatial arrangement. This is all due to his “writing” style of painting. Ni Zan’s practical consciousness of “writing” painting is specifically manifested in the following: his pen and ink technique is the flat movement of horizontal and vertical lines; his interest is in the “writing” of literati; his state is improvisation; and his scale of judgment is assessed by his “carefree style,” which is close to the principle of technique. From this point of view, “applying calligraphic techniques in painting” became Ni Zan’s conscious artistic practice for pursuing the beauty of pure lines. More importantly, in the process of applying calligraphic techniques to painting, he also incorporated his own talent and mind into the lines of brush and ink so that the blend of his poetry, calligraphy and painting went beyond the technical level and into the spiritual level. Therefore, “writing” imparted to Ni Zan’s paintings the aesthetic characteristics of simplicity with abundant meaning, emphasizing brushwork and the independent value of the artist’s subjectivity. It is also a way of practicing the spirit of tranquility and relaxation at a deeper level.

The Expression of “Writing” Painting

Ni Zan knew that calligraphy and painting were the same, and the addition of calligraphy gave his paintings a whole new interpretation in terms of his experience of nature and his knowledge of traditional methods. For example, the application of Chinese brush techniques for square and round shapes (运笔的方圆), the speed and slowness of the middle and side of the Chinese brush (中侧和快慢), and the intensity, wetness, and dryness of the Chinese brush and ink all contribute to imbuing the composition with both representational and calligraphic qualities. When we analyze Ni Zan’s paintings through textual and graphic corroboration [19], we can see that the expression of Ni Zan’s “writing” approach to painting mainly lies in the following points.

The Inevitability of “Writing” Painting

In the history of Chinese painting, there is no shortage of literati painters who have employed the theory of applying calligraphic techniques to painting. However, there is a certain inevitability in why Ni Zan in the Yuan Dynasty refined and profoundly influenced this creative concept of “writing.” Ni Zan often took boat rides to enjoy the scenery and gradually spent his days amusing himself with calligraphy and painting after experiencing a decline in his family fortunes [11]. In his practice, he formed the aesthetic ideas of “carefree pen” (逸笔) and “not seeking any realistic form” (不求形似). His painting techniques became increasingly refined and mature. In summary, there are several reasons why Ni Zan had an inevitable draw to his aesthetic conclusions.

First, Ni Zan’s paintings were influenced by the mainstream literary trend of the Yuan Dynasty, which integrated calligraphy and painting (书画交融). In the early Yuan Dynasty, ink wash paintings quietly rose with flower-and-bird paintings, which originated in the Northern Song Dynasty and primarily depicted scenes such as withered trees, bamboo, and rocks. The movement to revolutionize the brushwork of literati painting was initiated by Zhao Mengfu, together with Xian Yushu and other friends. They had a close relationship and attained artistic transcendence through conceptual exchanges, which led to a major shift in the direction of the history of Chinese painting: “calligraphic techniques in painting.” This experimental “writing” approach used in ink wash painting was like a whirlwind that swept through the Chinese painting world, quickly becoming mainstream. The Yuan dynasty was a heyday of writing and painting, which followed Zhao Mengfu and others. As Li Zehou said, “The aesthetic principle of ‘vivid charm’ (气韵生动) emphasized in traditional Chinese paintings could no longer be reflected in [realistic] objects in the Yuan Dynasty but was instead reflected in all subjective consciousness.” The subjective consciousness here also implies the “writing” approach to painting. Meanwhile, due to the influence of the late Yuan dynasty, literati in the Wuzhong region gathered to promote in-depth intermingling of calligraphy and painting, and Ni Zan’s Qingmi pavilion (清宓阁) was an important place at that time. A group of painters and calligraphers discussed their art here, and the existence of this literati group deeply influenced Ni Zan’s concept of “calligraphic techniques in painting.” Ni Zan inherited the artistic conception of Xian Yushu and Zhao Mengfu that there was “a common origin for Chinese painting and calligraphy,” and the expression of his paintings shifted from realistic resemblance to lyrical expression. He particularly emphasized calligraphic brushwork as well as the high quality of the lines in the composition, which is prominently embodied in the ink and bamboo paintings [12].

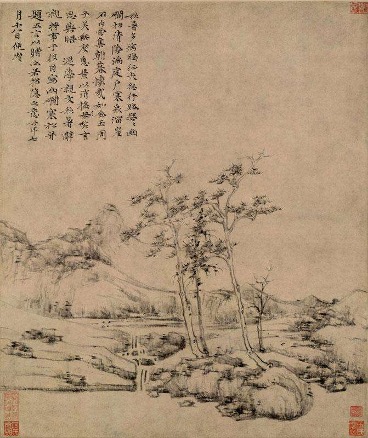

Second, Ni Zan was one of the most famous calligraphers of the Yuan dynasty and a first-class painter. As a master of both calligraphy and painting, Ni Zan held writing and painting as a part of his daily life and a lifelong aesthetic activity. This habit enabled him to develop a keen sense of pen-and-ink styles. Whenever he painted, this perception would subconsciously infiltrate his work, giving his paintings a strong calligraphic flavor. Ni Zan, in Inscription on Cao Yunxi’s Paintings of Pine and Stone (Volume 4), said, “Where the brush is waved, a majestic atmosphere emerges instantly, and even the leaves reveal a high level of skill, just like the large seal script [13].” The large seal script has ancient and simple strokes. He thus argued that bamboo leaves in paintings could be utilized in the manner of the use of large seal script. Similarly, Ni Zan mentioned in his Postscript to a Genuine Tang Dynasty Right Army Manuscript, “Calligraphy and painting both share a key point. When calligraphers write, they form a complete brushstroke, especially when copying other works; it is because of their mental concentration that the meaning of the pen and ink is coherent [14].” Ni Zan not only recognized the homogeneity of the brush in calligraphy and painting but also particularly highlighted the aesthetics and value of the “mental concentration” and the “connection of brushwork.” For him, “the art of calligraphy forms one’s awareness of line, external to the painting. In turn, this awareness is transplanted into the painting [15].” Therefore, he aspired for his paintings to pursue the writing quality in linework, with coherence, visual resemblance, and freedom in the brushstroke movement. This is intensively manifested in the paintings of bamboo and stone subjects, such as Painting of Tranquil Ravine and Cold Pine (Figure 2) and Painting of Frosty Bamboo and Stone (Figure 3). These paintings are made with calligraphic side strokes to portray the steepness of the mountains and rocks, swift strokes to mimic the texture of the stones, and skillful dry brush techniques to shape the firmness of the bamboos and trees.

Figure 6. “Bamboo Branches” (Sourced from: https://www.zsbeike.com/tp/7392135.html)