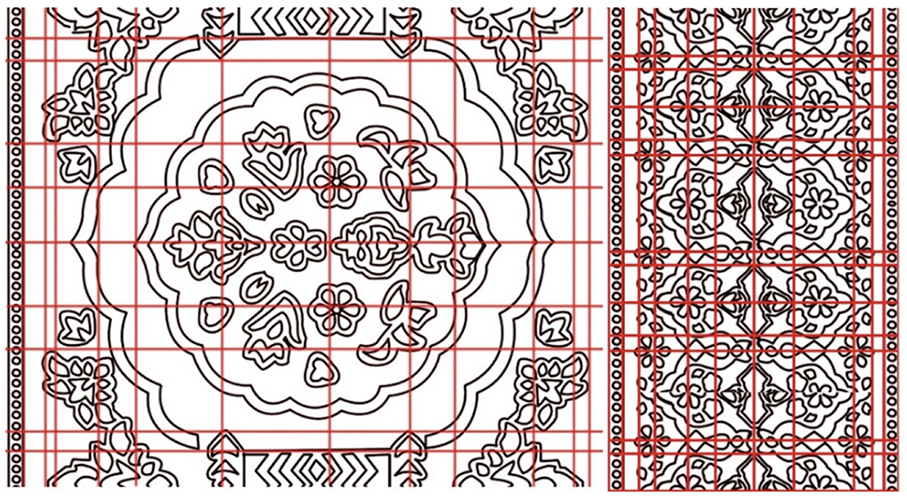

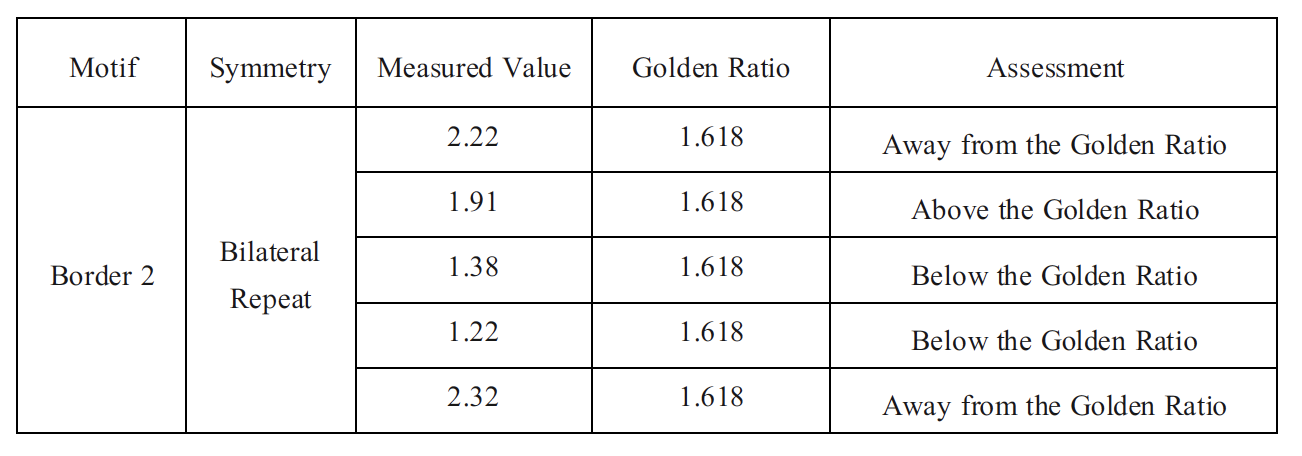

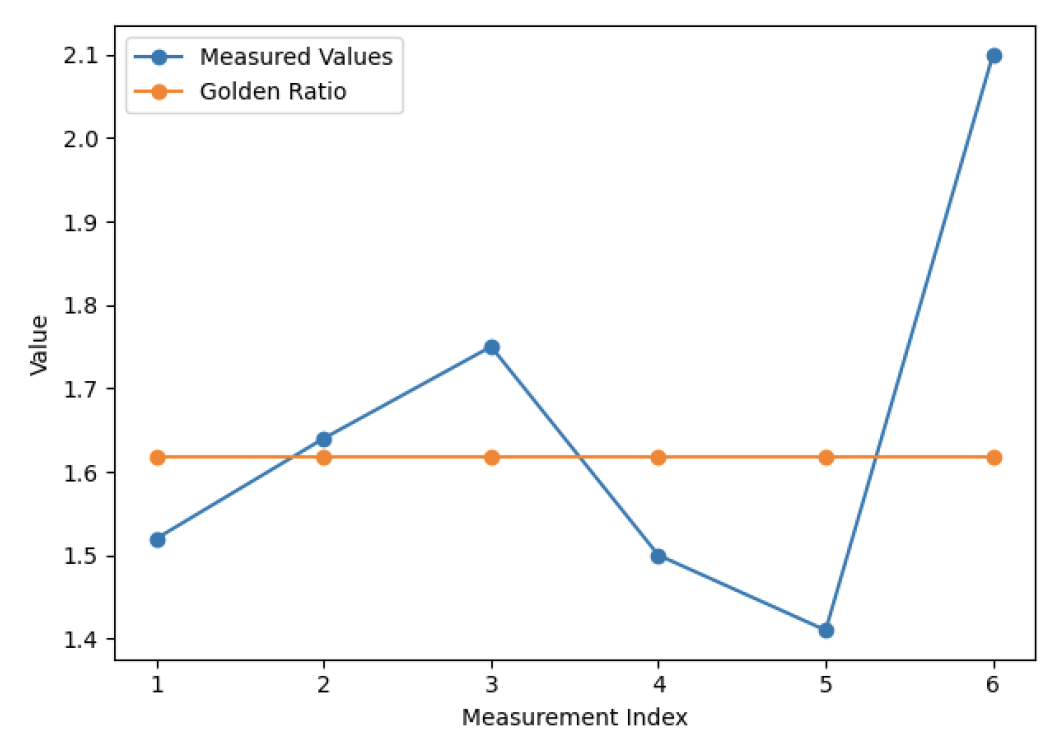

3.2. Border 2 (Bilateral Repeat)

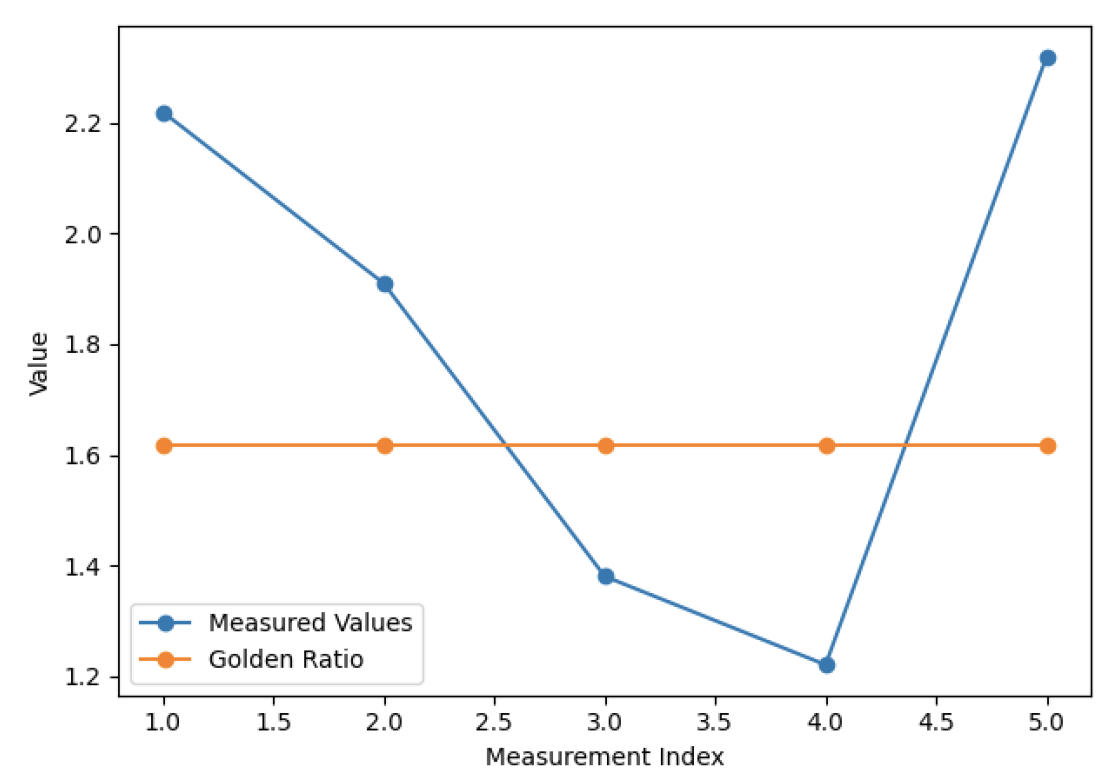

Border 2 is another bilateral repeated band (Figure 25). Its measured ratios are 2.22, 1.91, 1.38, 1.22, and 2.32. The largest values (2.22, 2.32) exceed φ by approximately 30–43%, and the smallest (1.22, 1.38) fall 15–25% below φ. None of these ratios approximated 1.618. Similar to Border 1, the design uses mirror-repeated units but does not align with the golden ratio. The border proportions appear to be determined by the traditional layout of repeating geometric blocks rather than precise mathematical ratios.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Ghaffor, Majid, Abdul Hafeez, and Faheem Tufail, "Ajrak Motifs Through the Lens of Geometry, Symmetry, and the Golden Ratio." JDSSI 3, no.4 (2025): 57-78.

AMA Style

Ghaffor M, Hafeez A, and Tufail F. Ajrak Motifs Through the Lens of Geometry, Symmetry, and the Golden Ratio. JDSSI. 2025; 3(4): 57-78.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

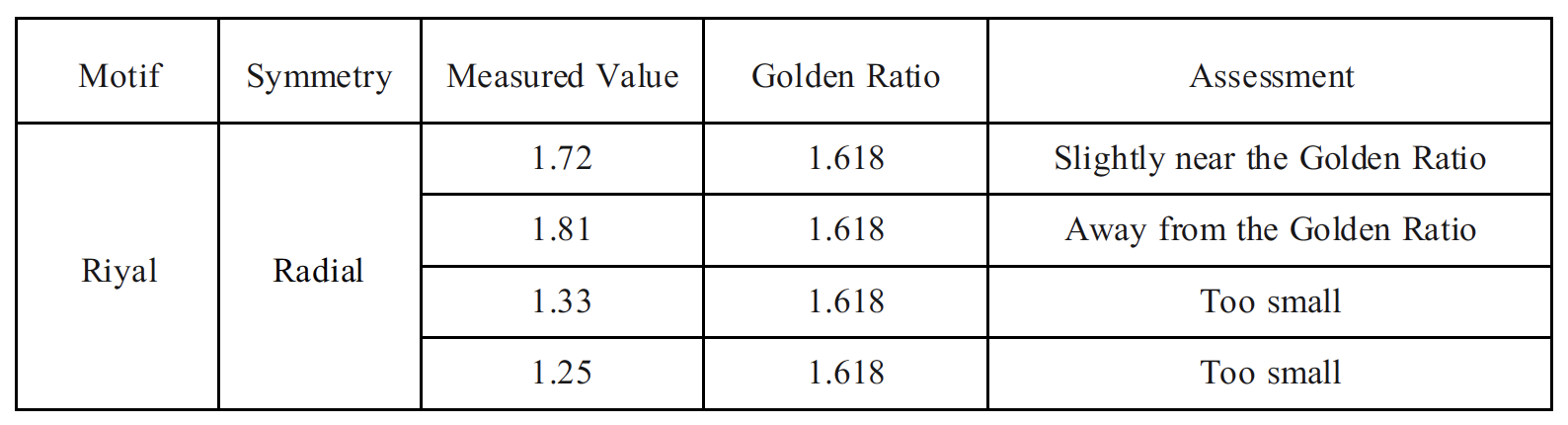

Geometric analysis of the six Ajrak patterns (Figures 4, 9, 14, 19, 23, and 27) showed that there was a very strong pattern in which symmetry and repetition prevailed, and the golden ratio was not significant in the patterns. Many motifs are highly tiled, with the most common being a fourfold (square) rotational symmetry and mirror symmetry, common in the block prints of Ajrak. For example, star and medallion motifs appear in square grids, and the border element repeats a basic block shape. Quantitatively, only one design out of the six exhibited a principal aspect ratio near φ (≈1.62). All other motifs had primary dimensions far from the golden mean (e.g., closer to 1:1 or simple rational ratios). In other words, an exact golden rectangle construction was essentially absent from the group. Instead, each motif is built from repeated stars, circles, and other simple geometric shapes. This reinforces the idea that Ajrak artisans favor exact timing and sacred geometry over applied proportionality formulas. In motif-level terms, several concentric circular or octagonal stars were featured nested in squares (yielding 4-fold symmetry), and one was a linear repeat along the border (1-D translational symmetry). Only the most elaborate star medallion came close to φ; its inner/outer scale ratio was ~1.62, but the remaining six motifs showed no trace of φ in their key element ratios. This implies that the emergence of the golden ratio is an accidental event and not intentional in nature.

Ajrak geometries are classic and shine through the motifs. All of them are universal eight-pointed stars, radial rosettes, concentric circles, and rectilinear repetitions. These are the grammatical rules of the Ajrak design. These patterns, rich in symmetry, are consistent with the historical tradition of the craft, as the Islamic Ajrak style focuses on abstraction and harmony. According to one source, the development of Ajrak has been firmly related to Islamic art and aesthetics, where the importance of geometric and symmetrical patterns is held and preferred, and symmetry is more valuable than representational forms. Motifs tend to carry strata of meaning; for example, fourfold symmetry may represent cosmic order or fertility. In fact, all the patterns and motifs of Ajrak have a symbolism, and the symmetrical patterns are usually a representation of the universe, nature, fertility, and spirituality [8]. In this regard, the perceived harmony of Ajrak is based on the symbolic geometry of the repetition of stars and circles; the designs appeal to a visual language of cultural and spiritual meaning as opposed to numeric aesthetics [9]. Even practitioners share this opinion. A craftsman complained that actual Ajrak is not dead: the hand-printed blocks are crooked, and this is their beauty. Machines can reproduce design, but not the soul of design. These kinds of testimonies imply that the craftsperson appreciates the intangible soul of a pattern (its irregular handmade quality and connotations) more than a calculated proportion.

These results correspond to the literature on Ajrak. The tradition of inherited motifs has been recorded by scholars such as Bilgrami in Ajrak. Ajrak designs and dates a cloud-shaped Ajrak motif to the denizen of ancient Indus and Mesopotamian art, emphasizing that patterns are inherited, as opposed to being constructed using the theory of modern design [10, 11]. Similarly, emphasizing the methods and cultural environment of artisans, interviews reveal that the makers do not think about proportions mathematically but rather in blocks and stamps. Similarly, Ajrak imagery is transmitted using apprenticeship and communal memory [12]. Our findings reflect this view: the appearance of ajrak patterns is not the result of some deliberate use of philosophy but rather the result of a visual convention, an inherited geometrical grammar passed down across generations. This pattern of transmission in artisan narratives is emphasized: knowledge is acquired through loyalty and a period of apprenticeship as opposed to time. Therefore, when we find a motif that bears almost golden proportions, it is more logical to suppose that it was made up of overlaying traditional elements (an 8-point star within a square) than by the designer targeting a precise mathematical constant.

In other words, the harmony of Ajrak appears to be rooted in its symbolic and cultural lexicon. Even the theoretical ideas of the golden ratio would not be familiar in the Ajrak workshop. Rather, the balance, repetition, and meaning inherent in every shape create beauty [13]. Speaking of Ajrak as a visual language, each motif tells a story. In a language like this, there are local rules (fitting a star in a square) to establish an overall order that delights the eye. It is a generalization of the idea of heritage crafts: the designs tend to get a satisfying proportion by using simple symmetries or ratios based on whole numbers, and any nearly golden values are by-products of those rules [14]. In summary, rather than aiming for the ideal φ proportion, the visual harmony of Ajrak is likely derived from its symbolic geometry, the cultural language of stars, circles, and colors, and the artisan's innate sense of balance.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- 1. Materials and Methods

- 2. Results

- 3. Border Design (Wat)

- 4. Discussion and Conclusion

- Study Limitations and Future Work

- Author Contributions

- Funding

- Acknowledgements

- Conflicts of Interest

- About the Author(s)

- References

The Border 2 bilateral repeat motif exhibits no consistent proportional relationship with the golden ratio, as the measured values vary substantially above and below φ (Table 6). Values within approximately ±0.1 of the golden ratio (1.618) were classified as “slightly near”; no Border 2 measurements met this criterion.

Figure 28 presents a line graph comparing the measured proportions of Border 2 bilateral repeat motifs with the golden ratio (1.618). The findings show that there is a wide range of variance among measurements, and the values are higher and lower than the golden ratio, which means no one-to-one proportionality.

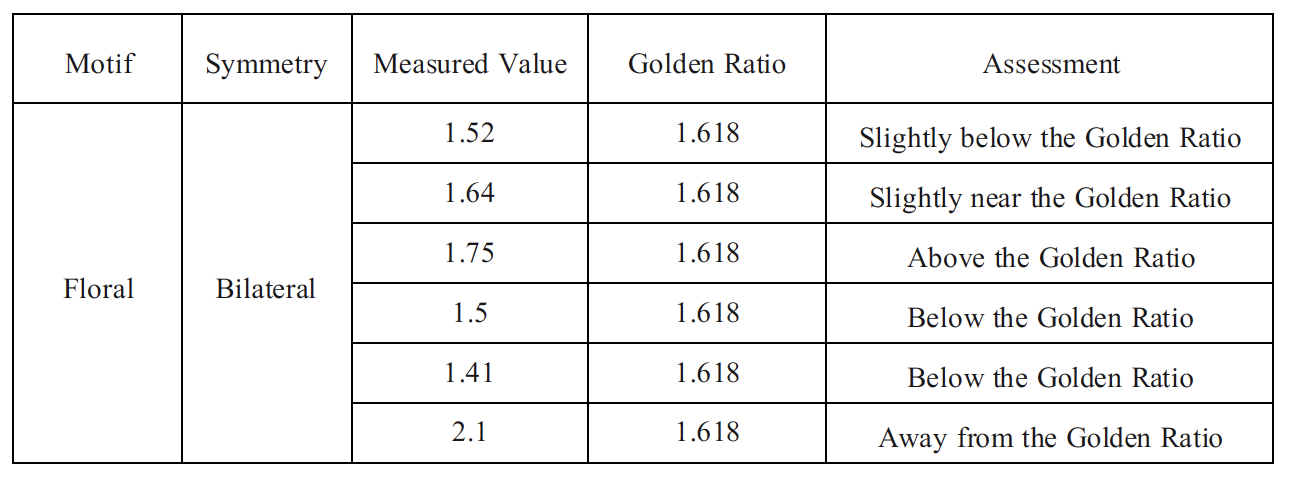

In general, the Floral Bilateral motif (Figure 16) was the only motif with a dimension (1.64) that was close to 1.64 (i.e., 1.5) (Table 4). The proportions of all other motifs were significantly different from 1.618. The pattern is mostly comprised of the courses or different ratios, which means that here, the Ajrak designs are not based on the strict use of the golden ratio, but on the intuitive, culturally grounded geometry. Without systematic φ-scaling, the symmetry and primary shapes (stars, circles, and repeats) are always in line with the conventional Ajrak block-printing techniques.

The designs of Ajrak borders are produced using the concept of translational symmetry, using a known repeat unit that is replicated linearly along a single axis. This type of repeat-based construction involves proportional relationships that are commensurable and grid-based, usually by whole number ratios or rational ratios to maintain continuity in block printing by hand. The fact that the golden ratio is an irrational proportion makes it structurally incompatible with modular repetition and cannot be continuously applied to repeating border units without interrupting the alignment. The lack of φ-based proportions in Ajrak borders is therefore due to mathematical limitations of translational symmetry and not due to the lack of geometric sophistication.

Ajrak Motifs Through the Lens of Geometry, Symmetry, and the Golden Ratio

References

1. Iftikhar, Fatima, and Suniya Tariq. "Historical and Contemporary Development of Textile Design." In Creative Textile Industry: Past, Present and Future of South Asian Countries, pp. 79-103. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, 2024. [CrossRef]

2. Wilson, Kimberley, and Cheryl Desha. "Engaging in design activism and communicating cultural significance through contemporary heritage storytelling: A case study in Brisbane, Australia." Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 6, no. 3 (2016): 271-286. [CrossRef]

3. Yang, Yongzhong, Mohsin Shafi, Xiaoting Song, and Ruo Yang. "Preservation of cultural heritage embodied in traditional crafts in the developing countries. A case study of Pakistani handicraft industry." Sustainability 10, no. 5 (2018): 1336. [CrossRef]

4. Fu, Chengchen, Jiping Wang, Jianzhong Shao, Dongjie Pu, Jiamei Chen, and Jinqiang Liu. "A non-aqueous dyeing process of reactive dye on cotton." The Journal of the Textile Institute 106, no. 2 (2015): 152-161. [CrossRef]

5. Azzaari, A. "Traditions and Features of Geometrical Decorative Pattern in Islam Art." The Scientific Heritage 74, no. 2 (2021): 3–7.

6. Farah Deeba, Khan. "Preserving the heritage: a case study of handicrafts of Sindh (Pakistan)." (2011).

7. Iqbal, Adeela, Zamrudin Abdullah, and Liza Marziana Mohammad Noh. "Unveiling the Threads of Traditional Icon of Sindh: A systematic review on the cultural significance, artistic elements and documentation of Ajrak." Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal 10, no. SI29 (2025): 213-221. [CrossRef]

8. Rasheed, Khwaja Amir, and Jahanzaib Afridi. "PRESERVING HERITAGE THROUGH FABRIC: THE ROLE OF AJRAK IN SUSTAINING INDIGENOUS SINDHI CRAFT TRADITIONS." Research Consortium Archive 3, no. 2 (2025): 562-572. [CrossRef]

9. Faraz, Ahmed. "Symbolic Significance of Star Motifs in Islamic Geometric Decoration and Contemporary Trademark Design in Pakistan." Al-Qamar 6, no. 3 (2023): 95-114. [CrossRef]

10. BILGRAMI, NOORJEHAN. "Ajrak: Cloth from the soil of Sindh." (2000).

11. Shihbaz, Hamza, and Zawiyar Khan. "ARTISANAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND CULTURAL IDENTITY: A POST COLONIAL ANALYSIS OF SINDHI AJRAK MAKERS." Liberal Journal of Management & Social Science 3, no. 2 (2024): 1-17.

12. Martínez, Elena, Michael R. Thompson, and Aisha Al-Harthi. "Traditional Crafts and Their Role in Pakistan’s Cultural Identity." Pakistan Journal of History and Civilization 1, no. 3 (2024): 8-14.

13. Abrar, Anum, and Wafa Pirzada. "CASE STUDY OF ANTI-CANAL ACTIVISM ON THE INDUS RIVER IN SINDH: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF PROTEST LANGUAGE THROUGH DIGITAL LINGUISTIC LANDSCAPE." Journal of Media Horizons 6, no. 2 (2025): 427-438.

14. Meisner, Gary B. The golden ratio: The divine beauty of mathematics. Race Point Publishing, 2018.

Author Contributions

Majid Ghaffor, as principal investigator, designed the study, selected Ajrak patterns, conducted geometric reconstruction and proportional analysis, prepared figures, wrote the first draft, and oversaw revisions and finalization. Abdul Hafeez analyzed geometric and proportional data, organized results, created tables and charts, and assisted with manuscript review and editing. Faheem Tufail handled visual documentation and design analysis, including photographing and reconstructing motifs, preparing geometric drawings, and refining the visual presentation and discussion.

Funding

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

The authors express special gratitude to the faculty members who offered great help in inspiring and supporting this research under the impartation of the faculty members. Their availability and the learning environment played a significant role in shaping the intellectual and analytical constructs of the study. We would also like to acknowledge the authors and researchers whose past research has contributed to this study. In particular, we focus on the publications and studies by Dr. Noorjehan Bilgrami, whose enormous output may provide historical and cultural insights into this investigation. It was inspired by local craftsmen and block print artisans of Sindh, and design skills, which were the focus of the given study. We are happy that they agreed to make their experience known and allowed us to record and study traditional Ajrak motifs. The authors also added that images were prepared, digitized using Adobe Photoshop, and analyzed for their geometrical properties using Adobe Illustrator. Finally, we would like to mention the institutional and peer support that assisted in the successful completion of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this research.

About the Author(s):

▪ Majid Ghaffor is a Pakistani textile designer, visual artist, and scholar with over fourteen years of experience in teaching, research, and creative practice. He is a Lecturer in the Textile Design Department, Faculty of Architecture, Design and Fine Arts, University of Gujrat, Pakistan. His work encompasses traditional and modern textile practices, including dyeing, weaving, screen and block printing, Ajrak production, pattern development, and research methodology. He holds a BFA in Textile Design from Government College University, Faisalabad, and an MPhil in Fine Arts from the University of Gujrat, with research interests in cultural heritage, Islamic art, Mughal and colonial motifs, and craft traditions.

▪ Abdul Hafeez is a Pakistani textile designer, researcher, and educator with fourteen years of experience in academia, industry, and creative practice. He is an Assistant Professor at the University of Gujrat, specializing in textile design, sustainable materials, experimental textiles, and textile-based sculpture. His work integrates sustainable production, natural dyes, zero-waste techniques, and innovative textile surfaces. He holds a Master’s degree in Textile and Clothing from Government College University, Faisalabad, where he researched natural dyes for 3D textile art, and has professional experience in textile design and teaching at national institutions.

▪ Muhammad Faheem Tufail is a Pakistani visual artist, curator, and educator based in Faisalabad. He holds a BFA in Textile Design and an MA (Hons.) in Visual Art from the National College of Arts, Lahore, with minors in product design and sculpture. Since 2005, he has been an Assistant Professor at the Institute of Art and Design, Government College University, Faisalabad. His work spans studio practice, curation, and visual arts education, focusing on space, cultural narratives, and contemporary visual language. He has participated in national and international exhibitions, residencies, and design fairs.

1 Faculty of Architecture, Design and Fine Arts, University of Gujrat, Gujrat, Pakistan

2 Faisalabad Institute of Textile and Fashion Design, Government College University Faisalabad, Faisalabad, Pakistan

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JDSSI. 2025, 3(4), 57-78; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jdssi2025.1231a43

Received: September 27, 2025 | Accepted: November 29, 2025 | Published: December 31, 2025

Majid Ghaffor 1 * , Abdul Hafeez 1 , Faheem Tufail 2

by

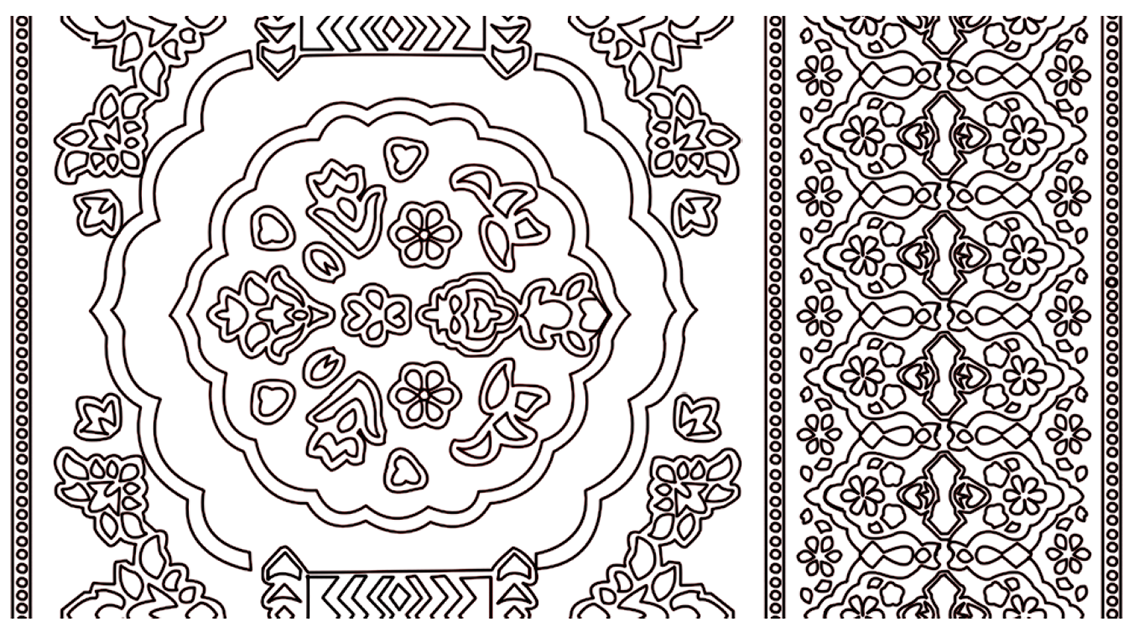

Abstract: Ajrak, a traditional block-printed textile of Sindh, is distinguished by its complex geometric designs, symbolic motifs, and deep cultural meaning. This study investigates Ajrak motifs through the analytical lens of geometry, symmetry, and proportional relationships, with an emphasis on the Golden Ratio. Five selected Ajrak motifs, including borders, were digitally reconstructed and geometrically measured, allowing for a detailed comparison of the actual motif proportions with a golden ratio value of 1:1.618. The visual analysis revealed the application of circular (radial) symmetry in motifs such as Riyal and Chānp, bilateral symmetry in motifs like Jaleyb, as well as proportional structuring within two borders. While proportional measurements such as 1.52, 1.64, 1.83, and 1.91 approximate the Golden Ratio, the data also demonstrate noticeable variation across motifs, suggesting an intuitive rather than mathematically exact proportional construction. Overall, the findings indicate that Ajrak artisans employ sophisticated geometric principles, including star polygons, concentric circles, repeated units, and mirrored motifs, to achieve visual harmony through symmetry and proportional balance. This study highlights how the aesthetic appeal of Ajrak is rooted not only in cultural heritage and traditional craft knowledge but also in the underlying mathematical order. By understanding these geometric foundations, this research enriches the contemporary appreciation of Ajrak and contributes new analytical insights into Islamic-influenced textile geometry and vernacular design knowledge.

Introduction

Ajrak is a block-printed textile with a high status in the cultural heritage of Sindh, Pakistan, and is considered an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Pieced together using cotton and lined with bright natural hues (indigo blue, red, black, and white), every Ajrak is decorated with elaborate geometric motifs, which demonstrate the works of their artisans, who have been passed down through history. Ajrak is not merely a garment but a symbol of the culture, a representation of Sindhi identity and pride, and is greatly appreciated both regionally and internationally [1]. Sindhi traditions dictate that Sindhi people are expected to gift an Ajrak to those they admire as a mark of respect. The fabric is worn during major occasions in their lives, such as festivals, marriage, and religious occasions, to signify culture and recognition.

Ajrak is historically considered one of the oldest existing textile art forms in South Asia [2]. Other historians date it to the Indus Valley Civilization (3rd millennium BCE), with the trefoil-patterned shawl around the Priest-King statue of Mohenjo-daro suggesting possible evidence of antique block printing in the Ajrak style. The history of Ajrak manufacturing across centuries prospered along the Indus River, extending to other areas, such as Kutch (Gujarat) and Barmer (Rajasthan). Patterns and applications may have changed; however, the principles of the craft, the carefulness of handwork, the application of natural dyes, and the insistence on harmonic design have remained true to the generations. This has been made possible by the resilience of Ajrak as a textile and an institution of culture [3].

A large portion of the available literature on Ajrak emphasizes the symbolism of the fabric, traditional patterns of creating it, and aesthetic inspirations. The labor-intensive process of block printing has been recorded by craft scholars: artists wash, dye, and print cloth in repeated sequences of soaking and stamping, which can include more than a dozen separate processes. Ajrak Wooden printing blocks, hand-carved with ornate patterns, are dipped in natural dyes and pressed onto the fabric to produce repeating motifs, which are the trademark of Ajrak. The background of the cloth is made by using natural indigo to give the cloth its handsome deep-blue hue, and the usual reds and black are done by using madder root, pomegranate rind, and iron oxide. This resist-dye process, which can take several weeks to complete a one-sided Ajrak, allows for a richly layered pattern with a visual complexity that is also known to be very durable [4].

The iconography and geometry of the Ajrak motifs are also crucial. Previous research has stated that Islamic art has influenced the design philosophy in Ajrak, where abstract, repetitive elements and symmetry have been employed instead of figurative imagery [5]. The majority of Ajrak patterns are therefore symmetrical, featuring stars, rosettes, trefoils, and other geometric patterns, often arranged in concentric patterns around the central field (jaal), which is a net-like pattern formed by interconnected motifs that create an overall sense of balance and unity to the edges (wat), the directional pathway or layout line that guides the placement and flow of motifs across the fabric in Ajrak refers to the directional pathway or layout line that guides the placement and flow of motifs across the cloth. These designs are characterized by radial symmetry (repeating around a center) and bilateral symmetry (mirror-image reflections), giving the impression of balance and infinity in their composition. Each motif has a meaning: the incessant interweaving patterns are often seen as signs of the cosmic order, fertility, and spiritual unity with nature. Cultural symbolism is overloaded in Ajrak color; indigo blue, earthly red, white, and black are all combined to symbolize the elements of the Sindh environment and heritage [6].

Although Ajrak has been celebrated and a significant amount of research has been conducted on its history and cultural meaning, little research has been conducted on its design from a mathematical or geometric perspective. As observed, some unfolded sides of Ajrak have not yet been explored [7]. However, there are inquiries into the design theory of the motifs of Ajrak: Are the pleasing proportions of patterns the result of intuitive folk knowledge, or are they based on formal principles of mathematics, such as the golden ratio? This study fills this gap by discussing six traditional Ajrak designs (both central motifs and border patterns) in terms of geometry and proportion. With digital reconstruction, every motif was broken down into its fundamental geometric elements and categorized according to its symmetry (radial vs. bilateral). The most important measures of the motifs are then contrasted with the golden ratio (approximately 1:1.618) to determine whether this famous proportional constant is hidden in the logic of the design of Ajrak. Through this exploration, we aim to uncover whether Ajrak artisans historically incorporated the golden ratio in developing their patterns or whether the observed aesthetics stem from traditional intuitive design principles. In summary, the guiding research question is as follows: Do the Ajrak motifs use the Golden Ratio for their development, or do they employ traditional proportional knowledge of intuition?

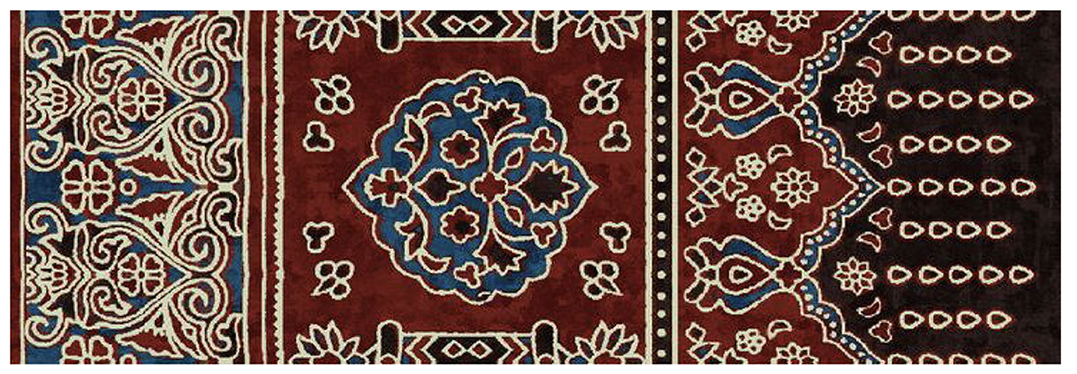

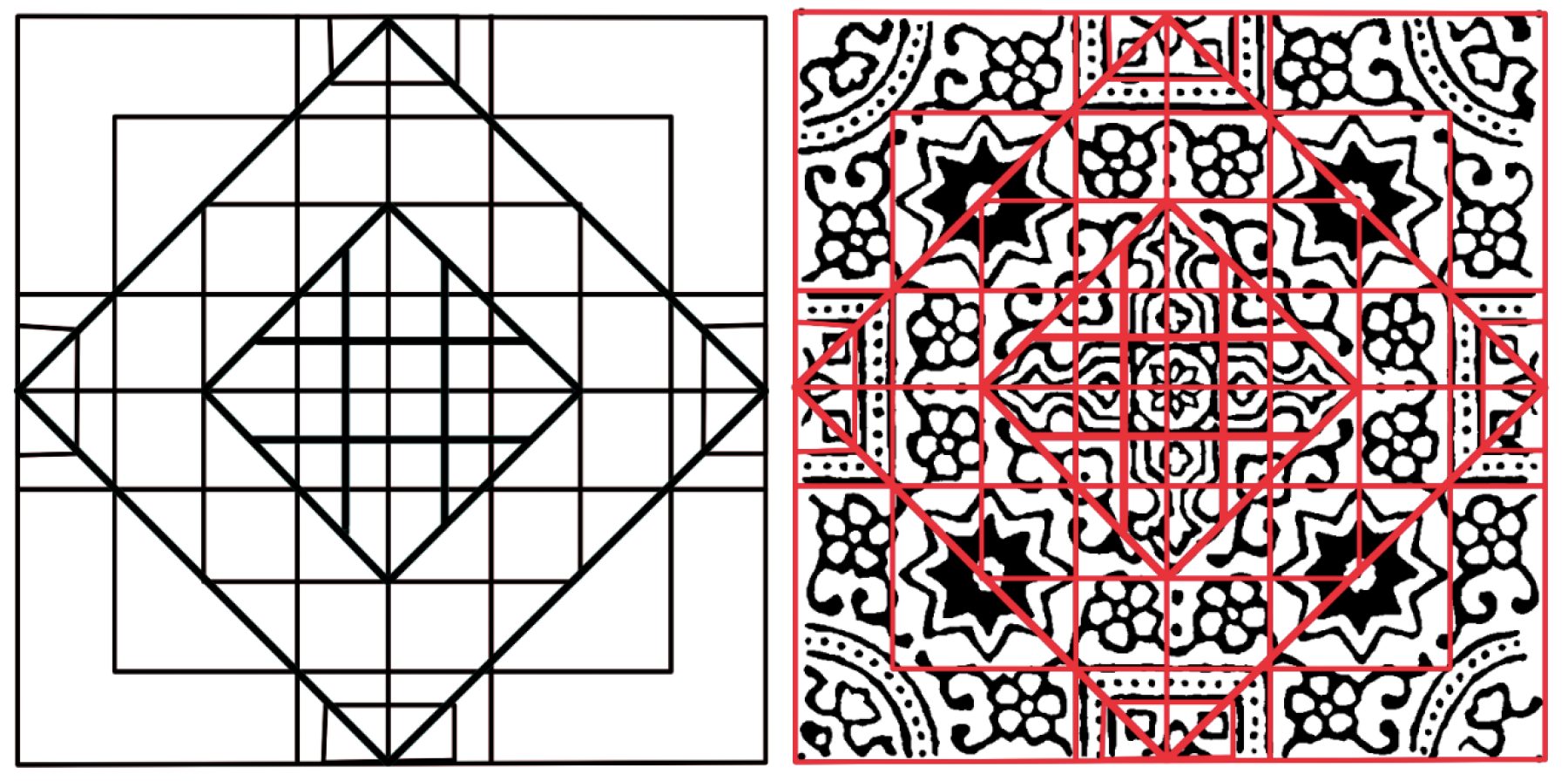

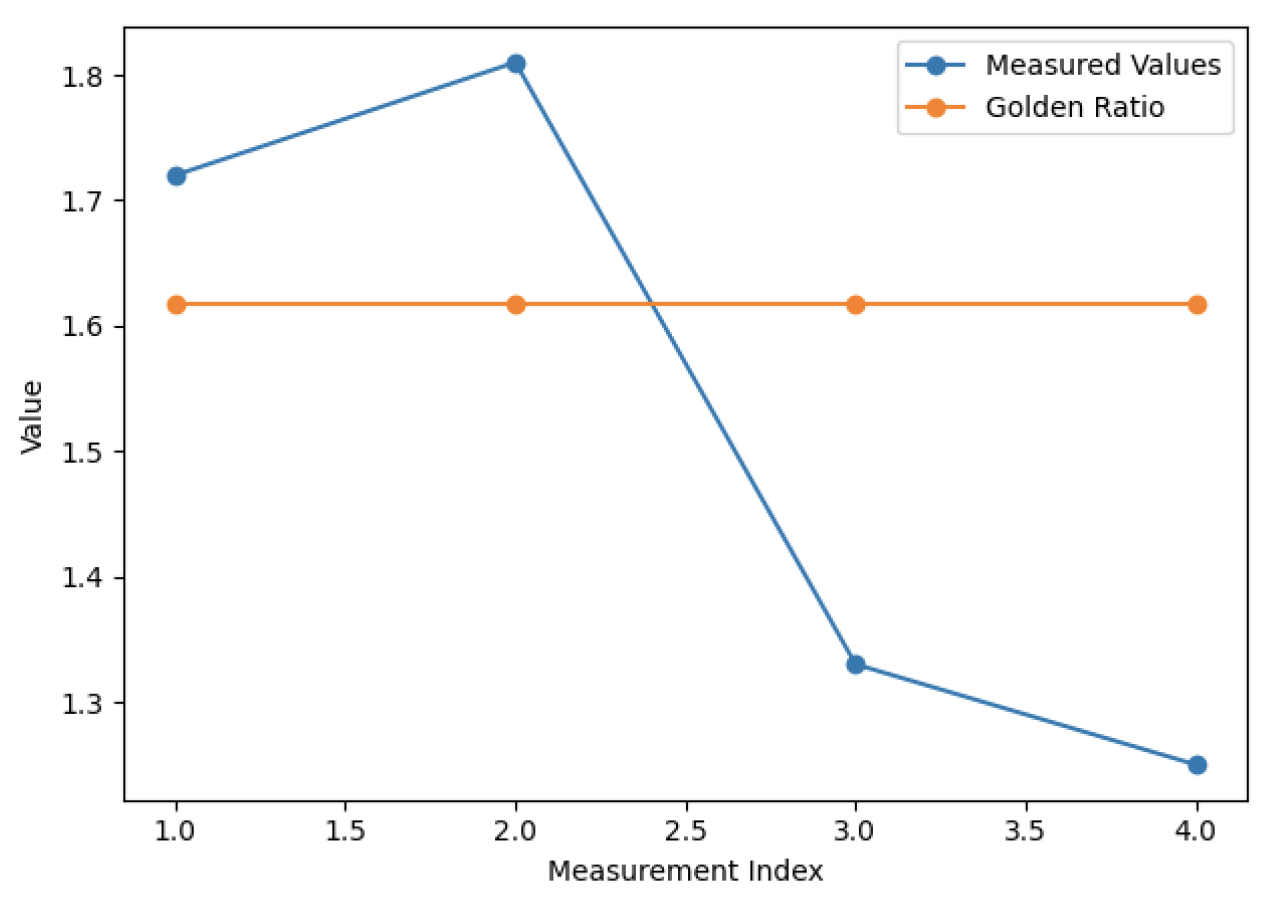

The measured proportions of the Riyal motif exhibit limited alignment with the golden ratio, with only one value falling slightly near φ, while the remaining measurements deviate from the reference value (Table 1).

Figure 5 shows the line graph comparing the measured proportions of the Riyal motif with the golden ratio (1.618), illustrating that only one measurement is close to the golden ratio, while the others deviate significantly.

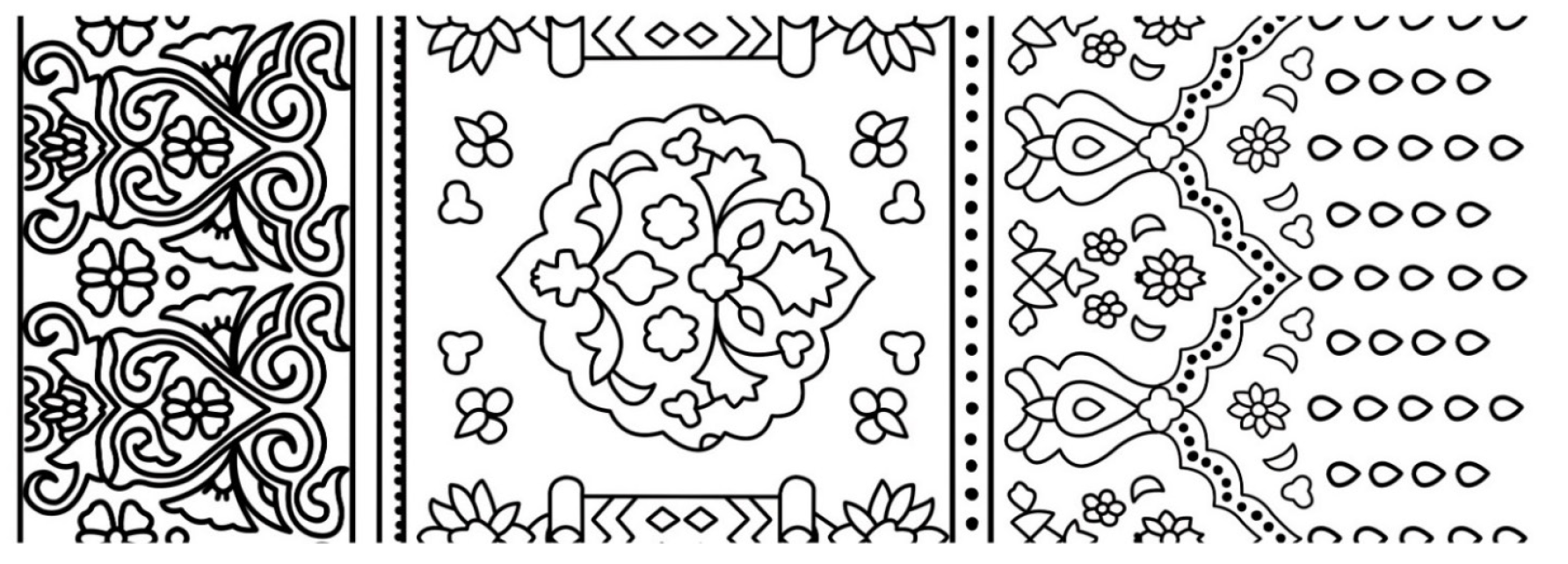

3. Border Design (Wat)

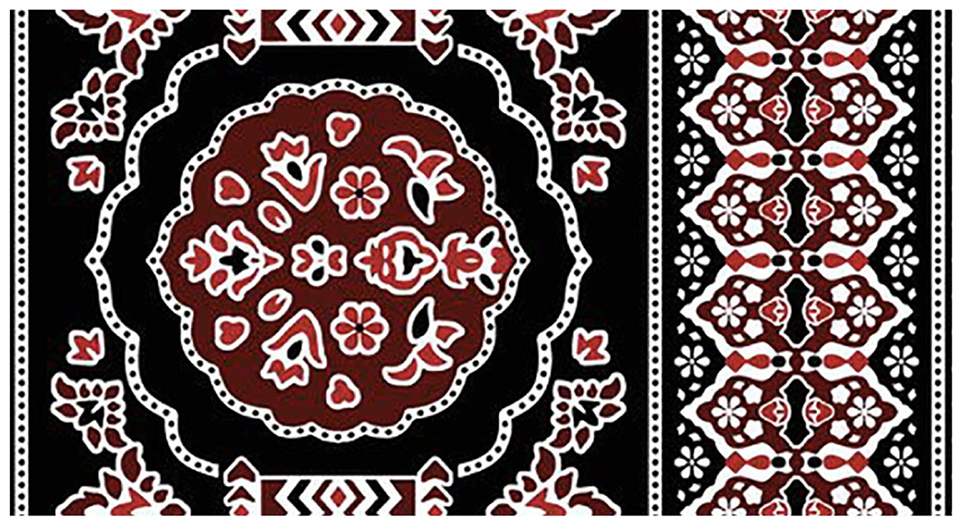

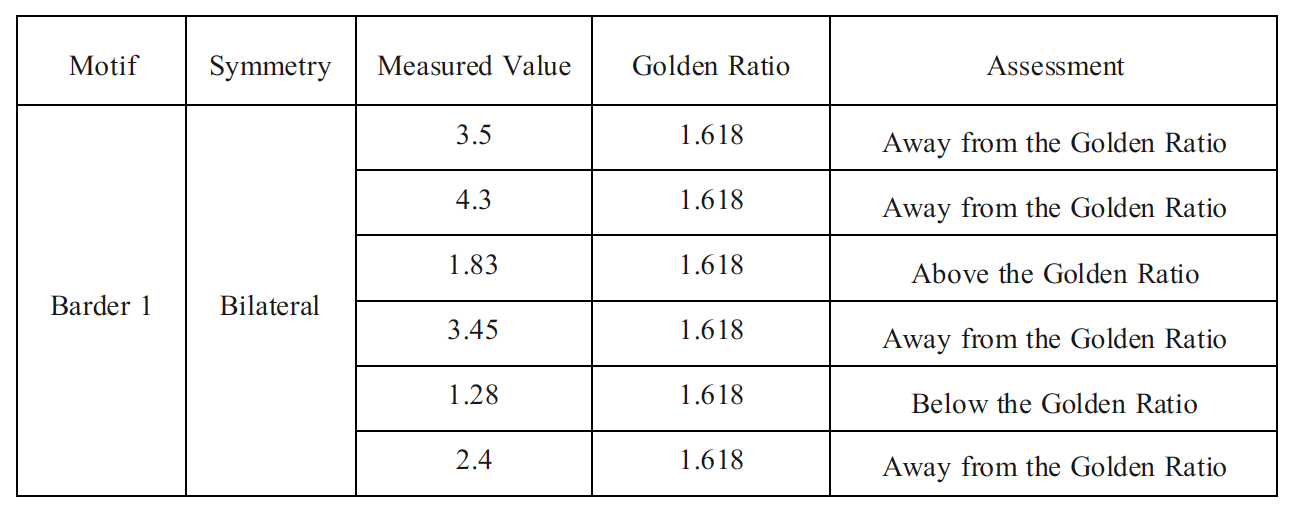

3.1. Border 1 (Bilateral Repeat)

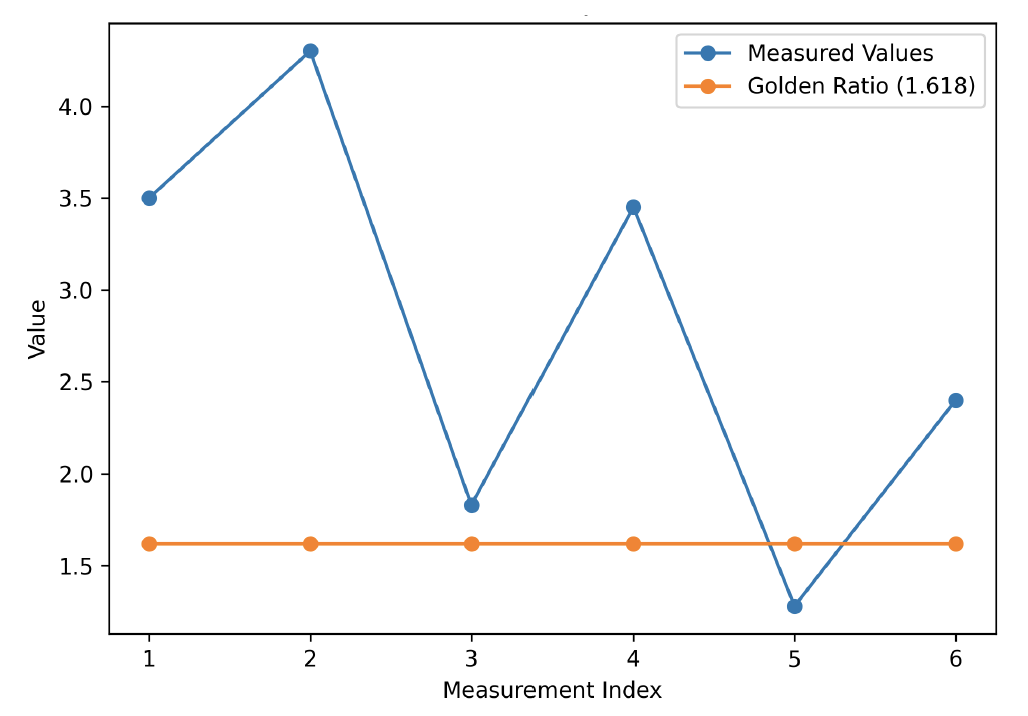

Border 1 is a repeat-pattern band with bilateral symmetry along its length. It contains elongated geometric features. The measured ratios are 3.50, 4.30, 1.83, 3.45, 1.28, and 2.40. These values are generally much larger or smaller than φ: the smallest ratio (1.28) and largest (4.30) differ greatly from 1.618. None are in the vicinity of φ. In fact, values such as 3.50–4.30 are more than twice φ, and 1.28 is well below. The proportions of this border show no golden ratio relationships. Its structure follows a traditional repeating grid of motifs rather than φ-based scaling.

Study Limitations and Future Work

This exploratory motif analysis has various significant limitations. The six motifs are not a representative sample and might not reflect the entire variety of Ajrak designs; other designs might exhibit other proportional characteristics. In addition, we obtained our measurements based on 2D digital images; pixel rounding or perspective errors might have slightly influenced the ratios we estimated. According to one of the artisans, machine-printed reproductions do not have the human touch; likewise, digitized photographs have the potential to add small geometric errors (folding, camera angle, image resolution).

These issues should be addressed in future research. More extensive coverage of Ajrak designs (with variations in regional design and old print) would be a test of whether the golden ratio is systematic. The measurement would be more accurate than plain photographs because 3D scanning or a calibrated image of physical cloth samples can be used. Importantly, ethnographic techniques would help to understand the design thinking of artisans: asking master printers about the positioning of blocks and the proportions they use would help to understand whether the ideas of φ ever make it into their process. A combination of geometry analysis and social research would be a better way to see the complete picture of the native geometry of Ajrak.

Our findings, together with the available Ajrak literature, provide evidence that the beauty of the craft is a result of tradition and ordered symbolism. Instead of abstract mathematical harmony, traditional Ajrak artisans appear to depend on a cultural grammar of design, based on handed-down motifs, spiritual symmetries, and the meanings of stars and circles. Through this, the aesthetic appeal of Ajrak lies in the centuries-old tradition of craft as its foundation, and (lesser) is supported, indirectly at best, through such traditional ratios as the golden mean.

- Limitations: The generality of the study is limited because only six motifs were examined. Digital tolerance mistakes (pixel rounding and perspective) are part of the measurements taken from 2D images.

- Future Directions: The robustness of these findings will be tested by extending the motif set. Measurement inaccuracies can be decreased by using high-resolution or 3D images of real textiles. Crucially, participant observations or interviews with Ajrak craftspeople could directly investigate whether their intuition is influenced by geometric proportions (such as φ) or whether they only use hereditary templates.

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Sampling and Visual Data Collection

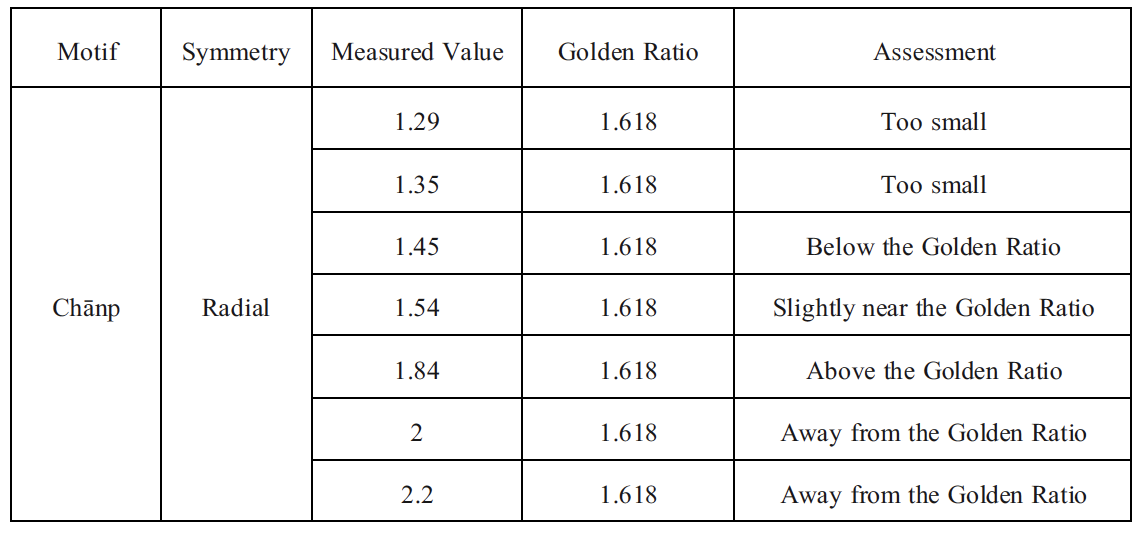

Six Ajrak designs were chosen, purposely selected from locally available products to encompass various motif types. Each sample had a central field motif and a border element, echoing the usual Ajrak design of the jaal (central panel) and wat (border) pattern areas. The motifs were selected to address all the common geometrical styles (e.g., star-shaped repetitions, floral repetitions, corner ornamentations) that were seen in traditional Sindhi, Ajrak cloth. Textile photos were taken in high-resolution digital photographs to provide precise color and details under the same lighting. These images (Figures 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, and 25) were used as the main visual information in the geometrical research. All the images were checked for distortion before analysis, and the slightest perspectives and scaling were used to ensure that the digital image size was close to the actual motif size. To classify and refer to it, the researcher referred to Sindh Jo Ajrak by Noorjehan Bilgrami, which is a detailed account of Ajrak motifs and design types. This offered contextual clues on the nomenclature of traditional motifs and assisted in informing the primary discovery of patterns of the early motifs (trefoils, eight-pointed stars, and rosette patterns) in the samples.

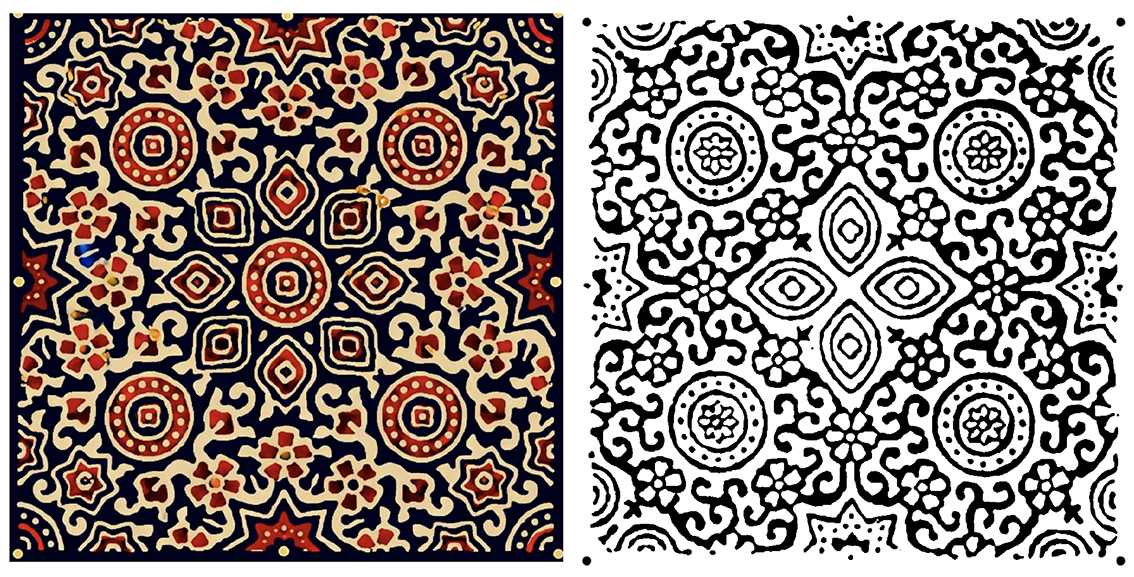

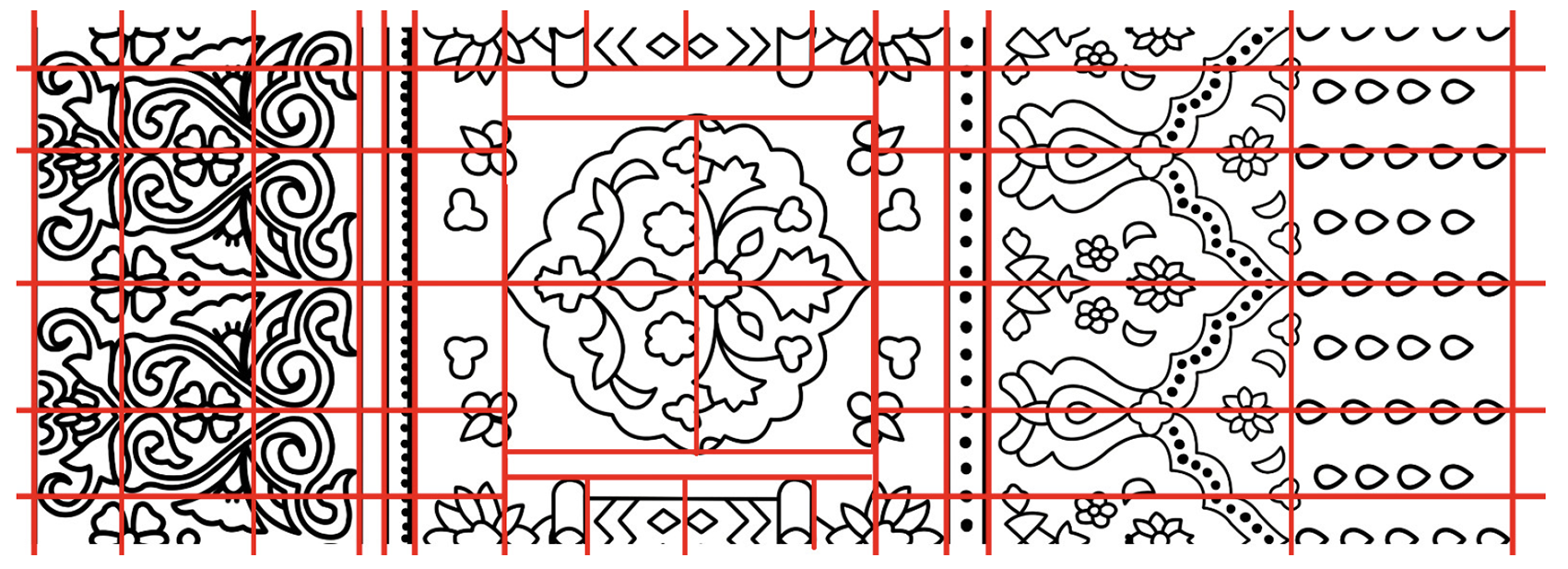

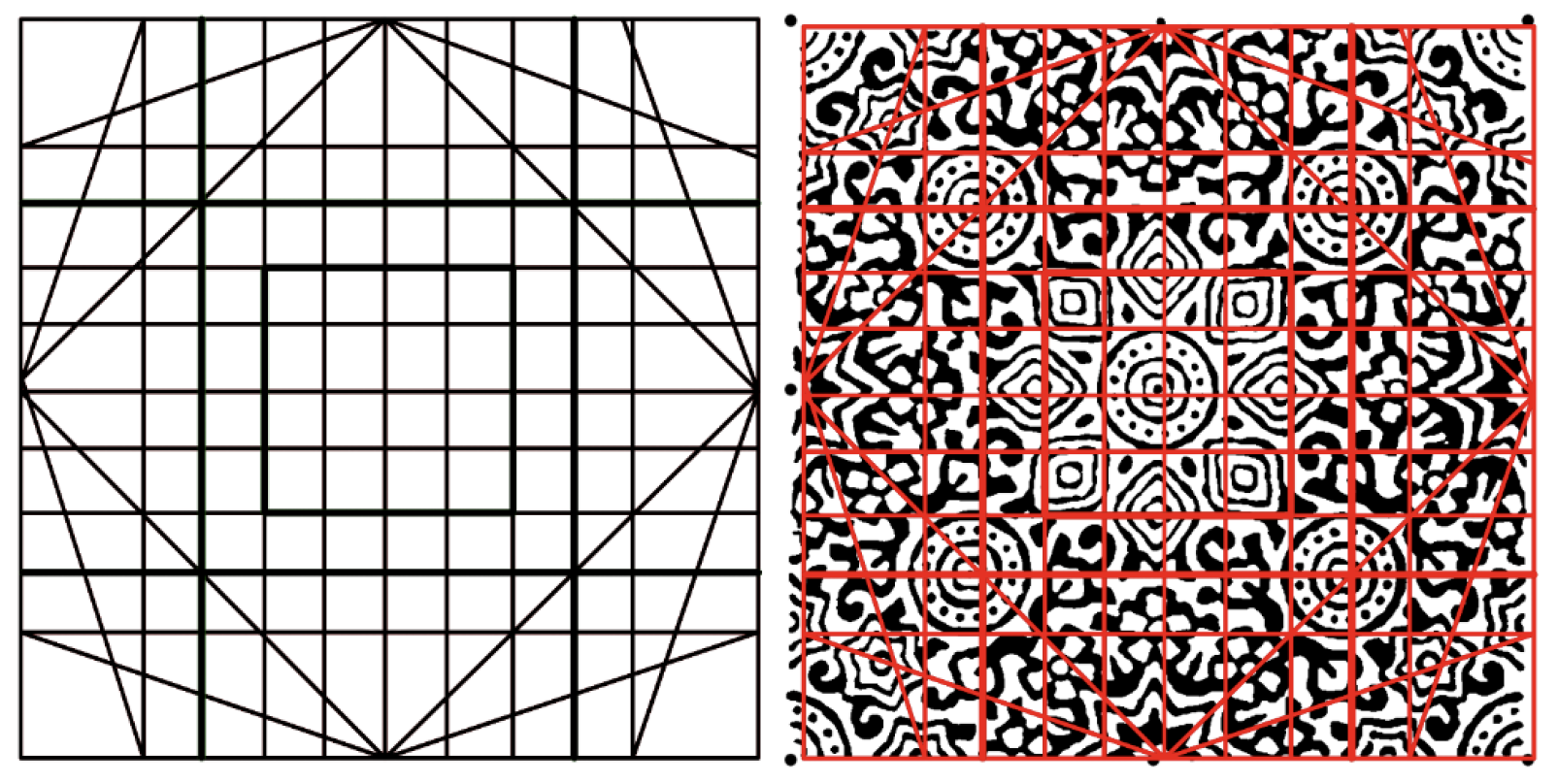

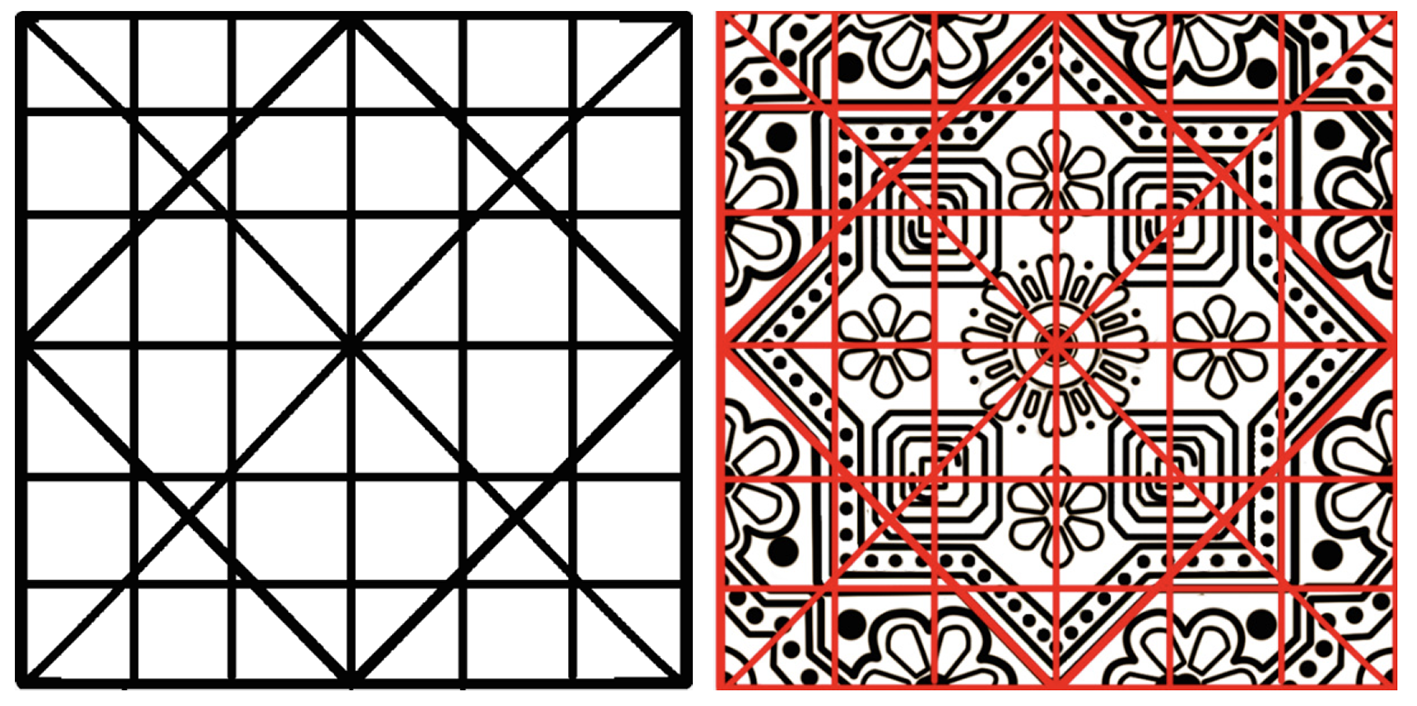

1.2. Digitization and Geometric Analysis Tools

Adobe Photoshop CC and Illustrator CC (Adobe Inc.) were used to analyze all image data. High-resolution images (Figures 1, 6, 11, 16, 21, and 25) were imported into the Photoshop application to enable close examination of the guides and exact overlaying (Figures 4, 9, 14, 19, 23, and 27). The software had a calibrated reference grid and rulers that could be enabled to enable scale drawing and ruler-based measurements on the images. The points of each motif (e.g., the middle of a circle, the tip of a star petal, and the corners of a repeat unit) are indicated on different digital layers (Figures 3, 8, 13, and 18). Making an inspired use of the digital overlay feature of the photographed motifs, the basic geometric elements (circles, polygons, and lines) were sketched using digital drawing tools of Illustrator, which essentially created a clean and geometric recreation of each design. This procedure enabled the researcher to determine the underlying geometric structures with high accuracy.

For example, when a motif had an octagonal star, an octagonal shape or star polygon like the Riyal motif (Figure 3) would be drawn to fit the outline, and where a floral motif was used, a corresponding circular guide would be superimposed to measure its radius. These digital tools allowed the analysis to appear as though it were a manual drafting technique, except that it was now possible to zoom and have the accuracy of on-screen measurement. The original image was not obscured by the overlays; thus, it could be checked in terms of alignment and accuracy with the real motif until working in layered files. The digital overlays also allowed testing transformations, including copying and rotating units of the motifs to experiment with symmetry.

2. Results

This section presents a geometrical analysis of the chosen Ajrak patterns in relation to the measured proportions and the golden ratio (1.618). Proportional relationships were recorded and evaluated using tabulated data (Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6) and line graphs (Figures 5, 10, 15, 20, 24, and 28) by using visual measurements of radial, bilateral, and bilateral repeat patterns. The findings support the existence of different proportional behavior differences between various motif types, which proves to be a quantitative foundation for analyzing the presence and range of golden ratio alignment within the structure of Ajrak designs.

2.1. Riyal Motif

The Riyal pattern is a star-shaped (radial) design, probably consisting of concentric circles and pointed stars in Figure 1. The measured ratios were 1.72, 1.81, 1.33, and 1.25. All these values lie outside the immediate vicinity of φ=1.618. The largest ratios (1.72, 1.81) exceed 1.618 by approximately 6–12%, whereas the smaller ratios (1.33, 1.25) fall well below φ (Table 1). None of the ratios is sufficiently close to φ to be considered approximately golden. This suggests that Riyal’s layout is driven more by traditional visual balance and grid-based geometry than by a strict φ proportion.

1.4. Measurement of Proportions and Golden Ratio Evaluation

Quantitative measurements were obtained from scaled drawings to test the proportional relationships with each motif geometry. The authors measured the important dimensions of the geometric construction in pixels using the Photoshop measurement tool, and the calibrated grid converted the pixel measurements into a consistent unit in the real world (for comparison with other measurements). Examples of measured structures include the diameter of a central motif, the spacing between the centers of repeating patterns in a border strip, the length and width of the petals of a star, and the distance between concentric patterns. Each motif was tabulated in terms of its measures. The proportional ratios were computed using pairs of dimensions that illustrated an aspect of the part-to-part or part-to-whole relationships. The examples show the ratios of the outer circle diameter of a motif to the diameter of an inscribed star and the ratio of the repeat length of the border pattern to its height.

All the ratios calculated were compared to the classical Golden Ratio (approximately 1:1.618, abbreviated as φ). The golden ratio was selected as a point of reference because artists and designers have traditionally considered it an example of perfect harmony and beauty in composition. Practically, the numerical value of each motif ratio was compared with 1.618 to determine whether it was close to this value. If the ratio values were in a narrow range (approximately a 5 percent range) of 1.618, the proportion of the motif was in the golden proportion. Since the design of Ajrak is handcrafted, the accuracy of the golden ratio values was expected to achieve rigor; each of the key dimensions (where possible) was measured multiple times independently and averaged, which reduced the possible error caused by pixel outbursts or minor distortion of the image. In each case, all the calculated ratios were articulated in the context of the design structure of every motif to identify whether the golden ratio association, where applicable, could be a purposeful element of the design of that motif or merely an approximation of the golden ratio. This quantitative proportional analysis, in combination with the findings of symmetry, was an analytical model to determine the extent to which the geometry of each Ajrak motif was in accordance with the classical principle of harmony design. The outcomes of each motif were cross-compared with the qualitative accounts of direction in the reference book of Bilgrami (for example, to determine whether traditionally sacred motifs were based on golden ratio proportions), thus combining empirical quantification with design knowledge in the assessment.

1.3. Symmetry Identification and Pattern Deconstruction

Using the prepared overlays (Figures 4, 9, 14, 19, 23, and 27), all the selected motifs were graphically dismantled into their essential parts, and the characteristics of their symmetry were recorded. The methods used to analyze the design were the principles of art visual analysis, visual structure, and composition (points, lines, shapes, and their symmetry). Each motif was balanced by a straight line through the center of the motif or other symmetrical axes, which were drawn using the Photoshop guide tool on top of the axes of symmetry (Figures 3, 8, 13, and 18). Bilateral symmetry was also explored by inserting a vertical and/or horizontal axis in the middle of the motif and determining whether the two sides of the mirror were coincident with each other. Digitally, one half of the motif was equivalently mirrored (flipped) across the axis to ensure that it was similar to the other half of the motif.

There was a study of radial symmetry (rotational symmetry) whereby the motif elements were rotated around the hub. For example, if a motif had a star-like shape (Figure 3), one segment or petal was similarly rotated by the theorized angle (e.g., 60°) to check a six-fold rotational symmetry to ensure that the same shapes would recur in a complete circle. The fundamental repetition of every pattern was determined by cutting out one repeat of a given pattern (one unit of a border repeat, one quarter of a larger medallion in the middle) and confirming that this repeat was reproducible by those repeating the entire pattern. This process was performed with vector drawings; with Illustrator, single units of motifs could be cloned and tiled or turned to experiment with the repeat pattern (Figures 2, 7, 12, 17, 22, and 26). The process was made possible by a digital ruler and grid, which guaranteed the consistency of the measurements of the spacing and alignment of the repeats. The complex interweaving of shapes and flowers of the motifs was simplified to geometric primitives (e.g., concentric circles, stars, and interlocking polygons), and its structure was charted with respect to symmetry acts (axes of reflection or rotation degrees). This methodological procedure adheres to the traditional research on symmetry in textile design, where the boundaries of motif shapes are defined, and a set of symmetry axes is created to separate the motifs into congruent pairs. Every symmetry (e.g., whether a border had a two-fold mirror symmetry or a central motif had four-fold rotational symmetry) was noted in the geometric profile of the motif.

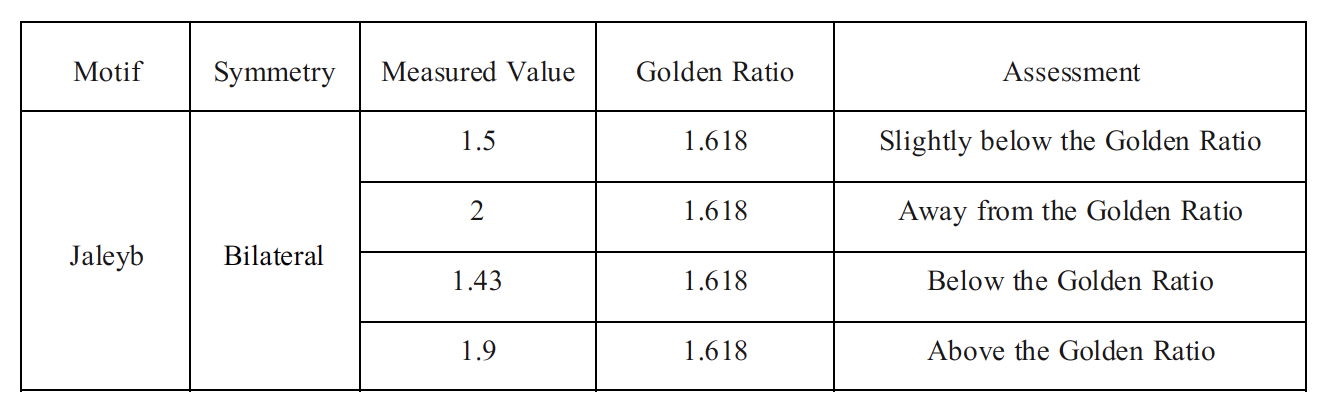

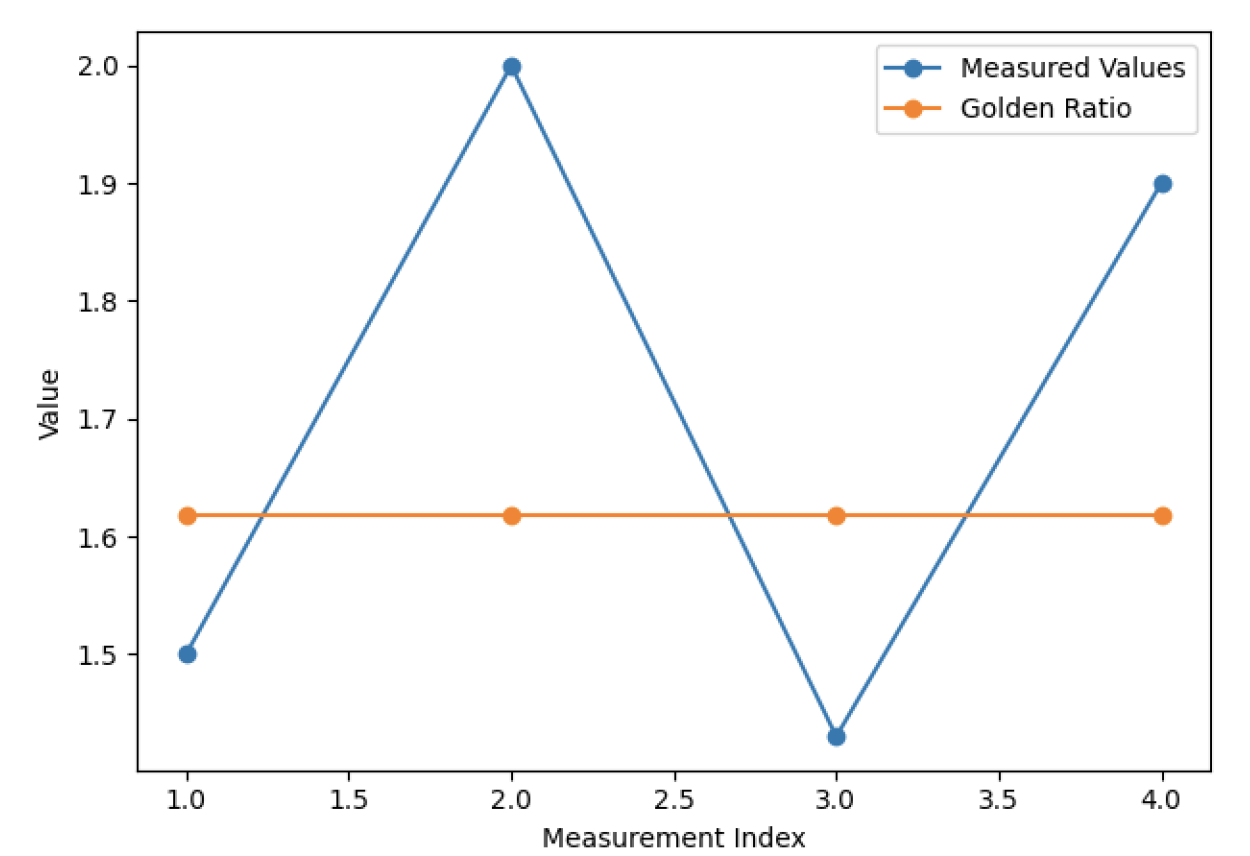

2.3. Jaleyb (Bilateral)

The Jaleyb is a bilateral central motif with mirror symmetry. It likely features two mirrored halves of an abstract or floral geometric shape (Figure 11). Its proportions are 1.50, 2.00, 1.43, and 1.90. Here, 1.50 is approximately 7% below φ, whereas 1.43 is approximately 12% below. The higher values of 1.90 and 2.00 exceed φ by 17–24%. None of these values is close to 1.618. The design’s bilateral symmetry is clear, but its proportions do not align with the golden ratio. This mix of values suggests an intuitive construction rather than a precise mathematical scaling.

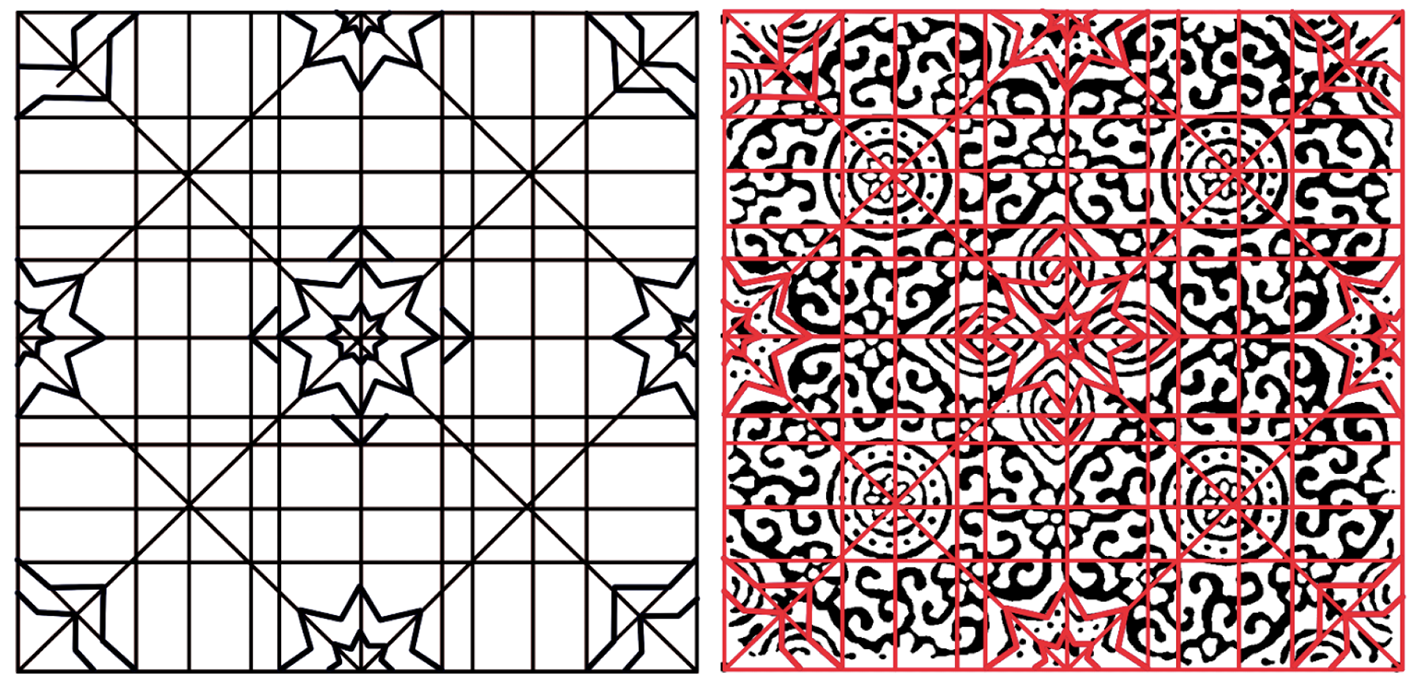

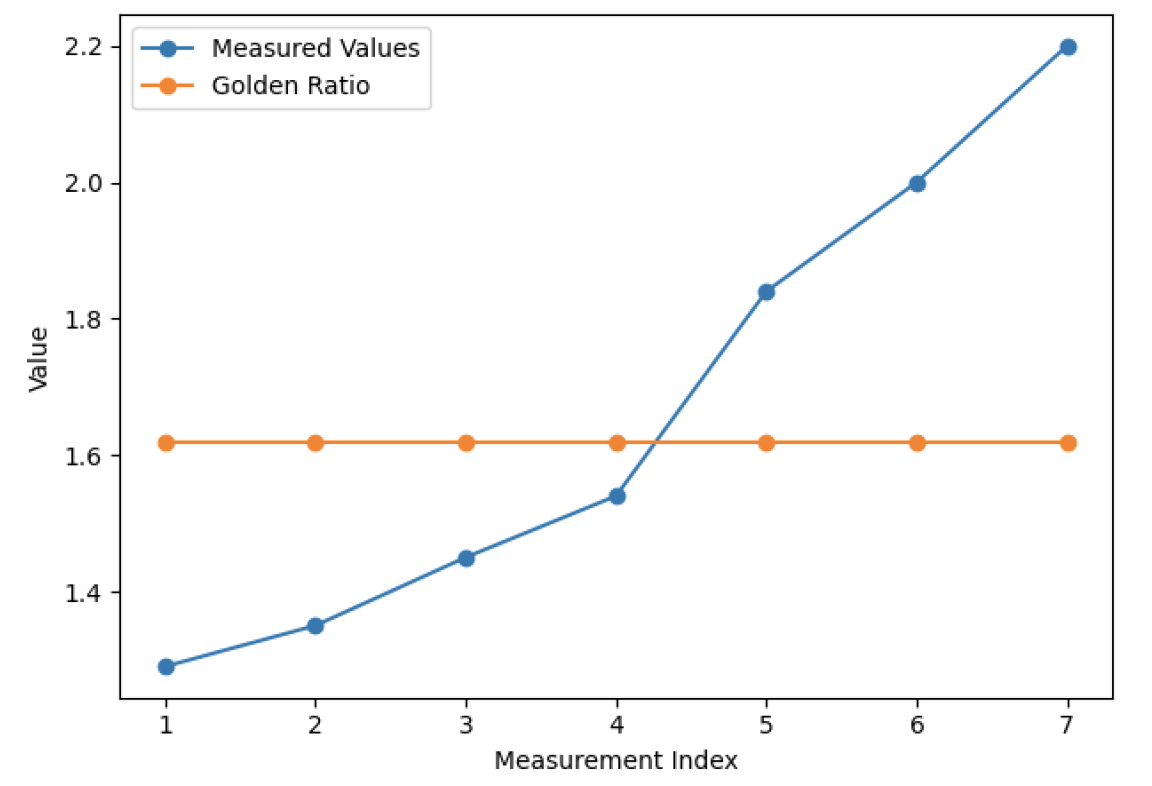

2.2. Chānp (Radial)

The Chānp motif (Figure 6) is also radial, resembling a sunburst or a floral medallion. Its measured proportions (1.29, 1.35, 1.45, 1.54, 1.84, 2.00, 2.20) span a wide range (Table 2). Only one value, 1.54, comes close to 1.618 (approximately 5% lower). The rest diverge more: two values are moderately below φ (1.29, 1.35), and several are well above (up to 2.20). Overall, the Chānp ratios do not cluster around φ. The moderately close ratio appears incidental, and the set of proportions does not indicate intentional golden-ratio scaling.

The measured proportions of the Chānp motif largely deviate from the golden ratio, with only one value (1.54) falling slightly near φ, while the remaining measurements are either below or significantly above this reference value (Table 2). Values within approximately ±0.1 of the golden ratio (1.618) were considered “slightly nearby.”

A line graph comparing the measured proportions of the Chānp motif to the golden ratio (1.618). The graph demonstrates that most measured values either fall below or exceed the golden ratio, with only one value approaching it (Figure 10).

2.4. Floral Bilateral (Bilateral)

This motif consists of a bilateral (mirror-symmetric) floral pattern that is repeated (Figure 16). Its measured ratios are 1.52, 1.64, 1.75, 1.50, 1.41, and 2.10 (Table 4). Notably, one ratio (1.64) is almost equal to φ (only ~1.3% above 1.618), making it the closest to the golden ratio among all measured values. Another ratio, 1.52, is moderately below φ (~6% lower). The remaining values (1.75, 2.10, etc.) are further from φ. Thus, the floral motif contains a single near-φ proportion but has substantial deviations. This indicates that although a one-dimensional ratio incidentally approximates φ, the overall design does not systematically employ the golden ratio. The floral motif’s shape likely follows traditional symmetry (mirror symmetry as expected in Ajrak) rather than an exact φ proportion.

The Jaleyb motif does not exhibit proportional alignment with the golden ratio, as all measured values deviate either above or below φ, with none falling within a close approximation (Table 3). Measured values within approximately ±0.1 of the golden ratio were considered slightly nearby.

A line graph comparing the measured proportions of the Jaleyb motif with the golden ratio (1.618). The results indicate that all measured values deviate from the golden ratio, with no proportion closely approximating it (Figure 15).

The floral bilateral motif exhibits partial proximity to the golden ratio, with one measured value closely approximating φ, while the remaining values deviate from the reference proportion (Table 4). Values within approximately ±0.1 of the golden ratio (1.618) were classified as slightly nearby.

The line graph compares the measured proportions of the floral bilateral motif with the golden ratio (1.618) (Figure 20). The results show that while some measurements closely approach the golden ratio, others diverge significantly, indicating a partial rather than a consistent proportional alignment.

The Border 1 bilateral motif demonstrates substantial deviation from the golden ratio, with all measured proportions either significantly exceeding or falling below φ, indicating a lack of proportional alignment (Table 5). Values within approximately ±0.1 of the golden ratio were considered slightly near, and no Border 1 measurements fell within this range.

The line graph (Figure 24) shows the measured proportions of the border design 1 comparing them with the golden ratio (1.618). The results show that while some measurements closely approach the golden ratio, others diverge significantly, indicating a partial rather than a consistent proportional alignment.