Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Current Situation and Issues of Porcelain Prop Usage in Chinese Historical Costume Dramas

- Research Background

- Methodology

- Problems with Porcelain Props in the Historical Costume Drama The Story of MingLan

- Examination of Song Dynasty Porcelain Categories and Lifestyle

- The Cultural Guidance and Recommendations for Porcelain Props in Historical Costume Dramas

- Author Contribution

- Funding

- Acknowledgments

- Conflicts of Interest

- Author Biographies

- References and Notes

(B) Human-Object Naturalness

Song Dynasty porcelains evidence this, featuring monochromatic glazes, tonal glazes, and single-fired glazes. These porcelains witnessed the prevalence of biomimetic adornments, such as reality-like flowers and carved botanical motifs. Compared to later periods, Song artisans achieved superior biomimetic technique, mirroring the literati’s restrained expression and cultivated moderation in both artistic and personal conduct.

(C) Interpersonal Naturalness

Song Dynasty paintings reveal unconstrained human behavior and facial expressions as well as interpersonal harmony. The elegance and subtlety of Song Dynasty porcelain lie in their forms and glazes (Figure 6). In China, most porcelain lovers know the saying, “celadon in the south, white porcelain in the north,” that is, southern kilns predominantly produced green-glazed porcelain, while northern kilns specialized in white-glazed porcelain [12]. As for westerners’ reference to “Chinese white,” it involves the white porcelain from the Ming Dynasty Dehua kilns in the south, which falls outside the scope of this discussion. Actually, based on collections in major museums, ongoing discoveries of kiln sites, and surviving artifacts, it is evident that northern China during the Song Dynasty did produce green-glazed porcelain. From the late Tang (750-907) and Five Dynasties (907-979) to the Northern Song period, northern kilns, such as the famous Yaozhou, Jun, and Ru kiln systems, fired green-glazed wares, which were deeply influenced by southern China’s Yue kiln celadon. The Ru kiln green-glazed porcelain, in particular, show clear traces of Yue kiln forms from the Five Dynasties and early Northern Song.

① green glaze;

② white glaze;

③ black glaze;

④ brown glaze;

⑤ bluish-white glaze.

Evaluating the Accuracy of Props in Chinese Historical Costume Dramas Based on Research into Song Dynasty Porcelain Culture: A Case Study of Porcelain Props in the Drama The Story of MingLan

by Zhen Zhou 1 * , Xiaoyun Ma 2

1 School of Design, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China

2 School of Foreign Studies, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2025, 3(1), 35-48; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2025.0630a11

Received: March 26, 2025 | Accepted: May 18, 2025 | Published: June 30, 2025

1. Current Situation and Issues of Porcelain Prop Usage in Chinese Historical Costume Dramas

Chinese historical costume dramas are set against the backdrop of a specific period in ancient China. The playwriting and performance are based on historical events or figures, or entirely fictional narratives. But the premise remains that the story unfolds in a defined historical era. Consequently, all props and cultural elements in the drama must align with or predate that time instead of postdating it, which is cultural and historical common sense. In today’s flourishing entertainment market where film and television industries thrive, various genres dazzle on screen, captivating audiences. Yet, beneath this glamour, the current situation of prop usage has sparked widespread concern and serious reflection.

A closer look at contemporary Chinese historical costume dramas reveals lamentable cultural inaccuracies. Anachronistic dialogue—often peppered with modern expressions—is already a fact. Historical architectural settings are also frequently overlooked due to budget constraints, with readily available locations as substitutes. However, the most obvious issues lie in the use of movable props in historical dramas. The main problems are listed as follows [1]:

Temporal displacement of props—the chronological misalignment of objects, where props depict items that did not exist in the specified historical period [2];

Spatial displacement of props—the inappropriate placement of objects in settings where they would not historically have appeared [3];

Social-class displacement of props—the mismatch between props and the social hierarchy, disregarding historical regulations on usage based on social class [4];

Functional displacement of props—the incorrect portrayal of an object’s functions in a certain period;

Technological displacement of props—the misrepresentation of manufacturing techniques, where props exhibit craftsmanship that was not developed in the depicted era.

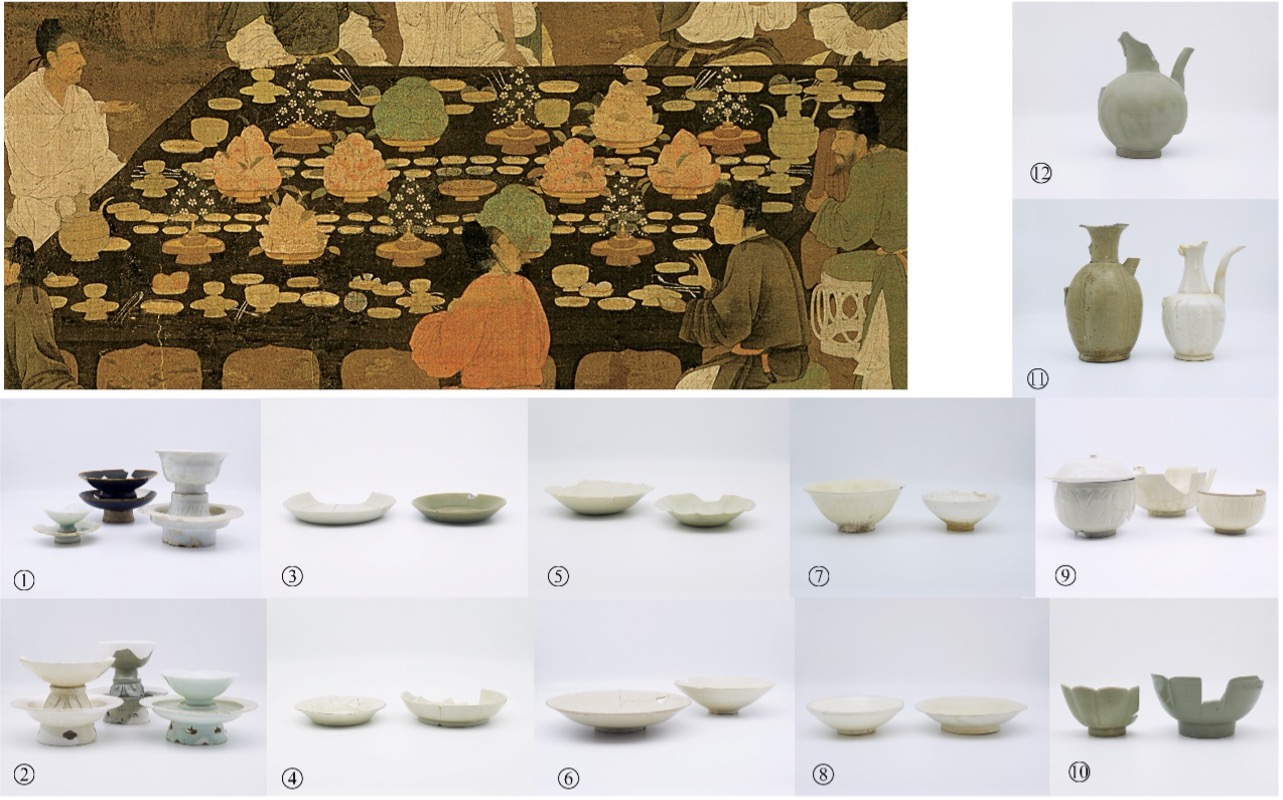

① ② Song Dynasty wine cup;

③ Song Dynasty flat-bottomed plate;

④ ⑤ Song Dynasty ring-foot plate;

⑥ ⑧ Song Dynasty flared-mouth bowl and hat-shaped bowl;

⑦ Song Dynasty bowl;

⑨ Song Dynasty lidded bowl;

⑩ Song Dynasty warming bowl;

⑪ ⑫ Song Dynasty ewer.

Note: The physical specimens are from the author's personal collection (for research and comparative purposes only).

Song Dynasty porcelain glazes can be broadly categorized into five major types: green, white, black, brown, and bluish-white (excluding other minor glaze colors from this discussion’s scope) (Figure 7).

For the drama, the prop crew conducted some preparatory research on Northern Song culture. For average audiences primarily focused on plot development, the porcelain props’ details might escape notice at first glance. Superficially, the team avoided blatant anachronisms by predominantly using celadon, white porcelain, bluish-white porcelain, and Jianzhan teacup—creating no immediate visual dissonance. However, for the Northern Song porcelain research, significant oversights emerge in the details, with primary inaccuracies in the following aspects.

4.1. Inaccurate Reproduction of Forms (Figure 1c, 3–6; Figure 2b, 1–4)

The imitated Northern Song Ding kiln white-glazed lobed dish with recessed waist (Figure 1c, 5) exhibits a flared trumpet-shaped mouth—an obvious manual shaping rather than the natural sagging deformation characteristic of thin-bodied porcelain during firing.

The bluish-white-glazed lotus-petal-carved hat-shaped bowl (Figure 2b, 3) shows its biggest error in the folded rim. The examination of Hutian kiln bluish-white-glazed specimens confirms no such form existing in Northern Song, making this bowl undoubtedly a modern potter’s fantasy.

Longquan kiln melon-ridged floral-mouth cup and saucer (Figure 2b, 4) contains multiple flaws:

- The pronounced melon-ridged fluting (especially spiral variants) never appeared in authenticated Northern Song Longquan specimens;

- Although frame motifs did exist on Northern Song porcelains, its design was strictly limited to crabapple flower pattern, heart-shaped cloud pattern, or auspicious ruyi-style cloud pattern—never modern heart shape but delicate and small in proportion [9].

4.2. Inaccurate Reproduction of Craftsmanship Techniques (Figure 1c, 3–6; Figure 2b, 1–4)

While maintaining a water-drop silhouette, the imitated Hutian kiln bluish-white-glazed ewer with incised floral patterns (Figure 2b, 1) features an overly crude junction between ewer neck and body. And the lotus-petal-mouthed warming bowl (Figure 2b, 1) has an excessively bulky form that loses the characteristic lightness, refinement, and delicacy of authentic Northern Song Hutian ware. Furthermore, the incised floral patterns and techniques differ significantly from the decorative styles of either Hutian or Ding kilns.

The bluish-white-glazed lotus-petal-carved hat-shaped bowl (Figure 2b, 3) presents another technical inaccuracy. Authentic Northern Song Hutian ware never executed double-sided carving in this manner. Firstly, interior and exterior patterns were never identical in that period. Secondly, the translucence of thin-bodied bluish-white porcelain would create visual chaos when backlit, as the incised patterns from both sides would interfere optically.

4.3. Inaccurate Prop Usage under Ritual Regulation

According to ancient Chinese ritual regulations, utensils bearing totemic or religious motifs were strictly reserved for sacrificial rites, religious enshrinement or imperial use. Their employment by commoners or even nobility constituted a grave breach of regulations. As exemplified by the items 3 and 4 in Figure 1c, and the item 3 in Figure 2b, strictly speaking, the inclusion of utensils with such motifs violates the ritual regulations of that historical period, resulting in cultural misinterpretation and distortion.

5. Examination of Song Dynasty Porcelain Categories and Lifestyle

The Chinese have always lived by the principle of “seven daily necessities”–fuel, rice, oil, salt, soy sauce, vinegar, and tea. Though alcohol is not listed among these necessities, it has never been absent from the dietary culture of Chinese daily life. Food culture, therefore, runs through the entire thread of cultural development across China’s dynasties, giving birth to related utensils—from primitive painted pottery to bronze ware, from Warring States Period (475-221BC) and Han Dynasty (206BC-220) lacquerware to early porcelain. These artifacts serve as tangible evidence of life in the agricultural society.

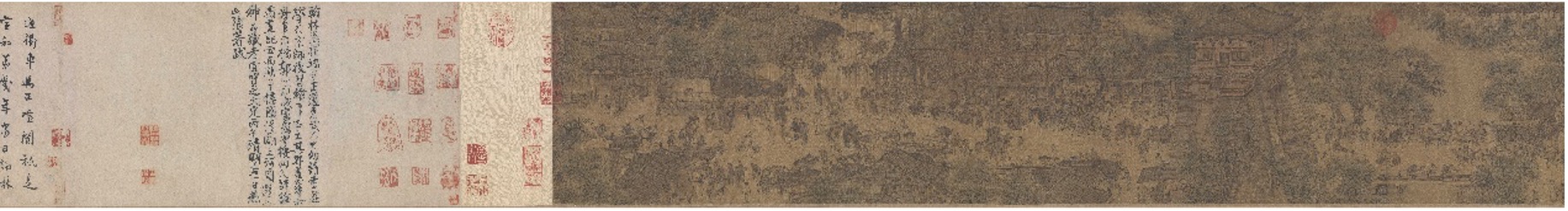

During the Northern Song Dynasty, people placed a high value on life quality and lifestyle attitudes, as can be identified from the paintings and surviving artifacts of that time. For instance, Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145)’s painting Along the River during the Qingming Festival (Figure 3) vividly depicts the daily life of commoners in Bianliang (today’s Kaifeng), the Northern Song capital. Besides, the painting Literary Gathering (Figure 4) by Northern Song Emperor Huizong (Zhao Ji, 1082 –1135) captures the elegant demeanor of the scholar-official class under imperial authority.

6. The Cultural Guidance and Recommendations for Porcelain Props in Historical Costume Dramas

Historical costume dramas are fundamentally works of entertainment, yet as productions based on historical settings, they inherently assume an additional responsibility: to authentically reconstruct historical realities or at least maintain cultural accuracy in their historical context. Failure to uphold this responsibility carries significant consequences for public perception—a concern that is by no means alarmist. Over the past two decades, various “fictionalized retellings” and “historical romances” set in the Ming and Qing dynasties have distorted public cognition of history and culture. Many viewers with limited historical knowledge, particularly adolescents, mistakenly accept these dramas as factual, having negative effects on their proper historical and cultural perspectives.

The substantial influence of historical costume dramas stems from their mode of mass communication. As a vehicle of popular entertainment, their primary function is to amuse audiences and consume time, while their secondary effect lies in driving economic growth of the entertainment industry, benefiting both cast/crew and derivative products (e.g., daily necessities, cultural trends). On a positive side, such dramas serve as a superficial yet accessible medium for cultural dissemination. On the negative side, precisely because of their superficial and often inaccurate portrayals, they risk distorting historical and cultural truths. Given that most viewers lack specialized knowledge of history or material culture, the ethical imperative falls upon producers to ensure responsible representation and dissemination.

Some may argue that historical dramas are not documentaries and thus need not adhere to strict accuracy and authenticity. Perhaps they should reflect on this: How many actually watch documentaries? Instead, the vast disparity in viewership between entertainment media and educational documentaries is evidenced by rating data and age group analyses.

Therefore, this paper focuses specifically on porcelain props as a case study, employing comparative material analysis to identify areas requiring improvement. By cross-referencing on-screen artifacts with authentic historical porcelain, we highlight discrepancies and propose measures to enhance authenticity.

To ensure the role of historical costume dramas, particularly porcelain props, in guiding accurate cultural understanding, the following suggestions should be considered:

- Historical costume dramas should not focus predominantly on the lives of royalty and nobility, but rather adopt the perspective of common people’s daily existence. Over the years, most of these dramas have revolved around palace intrigues and power struggles. This does not depict history—it is merely modern melodrama dressed in ancient costumes. The lives of ordinary people represent the true reality for the vast majority in those societies and serve as an authentic reflection of the entire social fabric. Moreover, such portrayals can help cultivate correct historical, cultural, and moral values among viewers.

- Historical research should be more rigorous, as it not only tests the comprehensive abilities of directors, producers, and screenwriters but also reflects their cultural literacy. Such research must extend beyond static elements like architecture, clothing, and artifacts to include dynamic aspects such as behavior, manners, and speech.

- Regarding the portrayal of porcelain culture in historical dramas, greater attention should be paid to details. Because porcelain reflect the lifestyles of the upper class and common people, serving as direct evidence of cultural aspects across the entire social hierarchy.

- Regarding the portrayal of porcelain culture in historical dramas, greater attention should be paid to details. Because porcelain reflect the lifestyles of the upper class and common people, serving as direct evidence of cultural aspects across the entire social hierarchy.

2. Research Background

Existing research on props in Chinese historical costume dramas primarily takes two forms: online commentary and historical comparisons, both documented and shared in written forms. Online commentaries tend to focus on plotlines, actors, characters, and costumes, emphasizing entertainment value and visual aesthetics, while historical comparisons center on the historical accuracy and authenticity of plot development, character portrayals, costumes, and set designs [5].

An examination of these written records reveals that, regardless of format, the discourse invariably revolves around two key dimensions: entertainment and “authenticity.” However, assessments of “authenticity” are generally limited to comparisons with historical facts, with little in-depth scrutiny of specific prop details. This situation is understandable, as meticulous verification of such details requires extensive data sources and interdisciplinary collaboration to achieve a high degree of accuracy [6]. Given these constraints, this study narrows its focus to the tangible verification of the porcelains and craftsmanship depicted in a historical costume drama The Story of MingLan, aiming to address issues of inaccuracy in these aspects.

① Hutian kiln bluish-white-glazed ewer with incised floral design, and lotus-petal-mouthed warming bowl;

② Northern Song Dynasty Ding kiln white-glazed lotus-petal-carved hat-shaped bowl;

③ Hutian kiln bluish-white-glazed lotus-petal-carved hat-shaped bowl;

④ Longquan kiln green-glazed ribbed foliate-rim cup with frame-lined saucer.

The porcelain culture of the Northern Song Dynasty can be broadly categorized into three major types based on daily life: utilitarian utensil (UU), decorative utensil (DU), and religious and sacrificial utensil (RSU). UU and RSU sometimes overlap in terms of utensil names but differ in form and decorative motifs [10]. For example, bowls, cups, and plates in the UU category were often plain-colored or decorated with non-religious motifs, such as sunflower, chrysanthemum, water ripple, orchid, butterfly, or bird patterns. In contrast, RSU featured intricate carving and incised motifs with religious and sacrificial symbolism, such as lotus petal, swastika, or six-petal gardenia patterns.

Another example is incense burner. In UU category, incense burners were typically small in size, simple in form, and minimally decorated. They were used in study room or tea room for fragrance enjoyment and mental focus, distinct from the religious behavior of chanting scriptures or offering prayers when there was RSU. Utilitarian incense burner does not develop a sense of religious ritual, but rather a habit of leisurely and refined living. The term “habit” is used here to emphasize the refined taste and quality of Song Dynasty life, in contrast to the forced pretensions of elegance often seen in modern lifestyles [11].

The leisurely refined life of Song Dynasty scholar-officials derived its essence from naturalness rather than rituals. The concept of naturalness manifests in three fundamental dimensions:

(A) Human-Nature Harmony

Song Dynasty paintings—landscape painting, bird-and-flower painting, and particularly landscape portraiture—position human figures in between the heaven and the earth. Depictions of individuals observing scenery, resting, laboring, or traveling (Figure 5) articulate the Song intellectuals’ attitude and yearning for the nature.

① Northern Song Dynasty Ding kiln white-glazed wine cup and saucer (or Yue Kiln mise celadon wine cup and saucer);

② Northern Song Dynasty Ru kiln flat-bottomed washer (or Ding kiln white-glazed flat-bottomed dish);

③ Northern Song Dynasty Yue kiln mise celadon bowl (or Ding kiln white-glazed bowl);

④ Northern Song Dynasty stemmed plate;

⑤ Northern Song Dynasty Yue kiln mise celadon shouldered ewer with warming bowl;

⑥ Northern Song Dynasty Yue kiln green-glazed jar;

⑦ Northern Song Dynasty green-glazed wine cup with black-glazed cup saucer;

⑧ Northern Song Dynasty green-glazed flared-rim plate;

⑨ Northern Song Dynasty green-glazed wine jar (practical term for plum blossom vase);

Note: Due to the darkened coloration of the painting, the exact kiln origins and glaze colors cannot be determined with certainty. Identifications are made primarily based on vessel shapes.

① Southern Song Dynasty Yue kiln green-glazed shouldered ewer;

② Jin-Yuan Period Longquan kiln green-glazed plate;

③ Southern Song Dynasty Longquan kiln plum-green-glazed lotus petal bowl;

④ Northern Song Dynasty Ding kiln white-glazed lotus-petal-carved hat-shaped bowl;

⑤ Imitated Northern Song Dynasty Ding kiln white-glazed lobed dish with recessed waist;

⑥ Basin, unknown origin;

⑦ Southern Song Dynasty Yue kiln green-glazed ribbed melon-shaped ewer;

⑧ Northern Song Dynasty Ding kiln white-glazed wine cup and saucer (or Hutian kiln bluish-white-glazed wine cup and saucer);

3. Methodology

Analyzing the accuracy of props in this drama is primarily based on the application of ancient porcelain culture within its specific social context. Therefore, specimen-based methodology and comparative methodology are employed in the research.

(A) Specimen-Based Methodology

This method involves systematic and detailed discussion from multiple perspectives, including the social background, hierarchical systems, cultural customs, and technological developments of the period in question [7].

(B) Comparative Methodology

This methodology entails comparing and correcting the porcelain props used in historical costume dramas against authentic porcelain artifacts from the era, focusing on their forms, craftsmanship, glaze colors, and usage.

4. Problems with Porcelain Props in the Historical Costume Drama The Story of MingLan

This paper takes the porcelain props in the historical costume drama The Story of MingLan as a case study for analysis. The drama is set against the background of a scholar-official family in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), seeking to depict the lifestyle and cultural value of the upper class during that period. Accordingly, in that historical context, the analysis of porcelain culture in the drama is conducted on four categories, i.e., food ware, wine vessels, tea ware, and incense utensils. By examining the usage and forms of porcelain props in these categories, the study identifies and corrects inaccuracies. Furthermore, these categories serve as a lens to explore the role and significance of Song Dynasty porcelain culture in social activities, thereby enhancing our understanding of Song society and the continuity of Han cultural traditions [8].

In the drama, food ware and wine vessels primarily include bowls, plates, basins, pots, warming bowls, wine cups and saucer (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Abstract

In an era of fast-food culture where entertainment often overshadows substance, a rigorous examination of Chinese culture should be conducted through the dissemination of entertainment, which is crucial for ensuring the public’s accurate understanding and interpretation of the culture. Movies and TV dramas, as vehicles of entertainment, often prioritize box office performance and online ratings as key metrics of success. Characters and plots may be fictional, but for those movies and TV dramas rooted in historical and cultural contexts, showcasing the essence of history and culture is of significance and necessity for the accuracy of such cultural depictions. Its significance lies in the faithful transmission of culture, while its necessity involves guiding the public toward a correct cultural understanding. This paper examines the porcelain culture depicted in the historical drama The Story of MingLan as a case study. The aim is not to utterly negate the effort put into the show’s props but rather to identify relevant issues and to analyze and discuss the discrepancies between the drama’s porcelain props and authentic artifacts/paintings from the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

Edited by: Eloise

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Zhen Zhou, and Xiaoyun Ma, "Evaluating the Accuracy of Props in Chinese Historical Costume Dramas Based on Research into Song Dynasty Porcelain Culture: A Case Study of Porcelain Props in the Drama The Story of MingLan." JACAC 3, no.1 (2025): 35-48.

AMA Style

Zhou Z, Ma XY. Evaluating the Accuracy of Props in Chinese Historical Costume Dramas Based on Research into Song Dynasty Porcelain Culture: A Case Study of Porcelain Props in the Drama The Story of MingLan. JACAC. 2025; 3(1): 35-48.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References and Notes

1. Wang, P. Z., and Z. Y. Chen. “60% of Respondents Dislike Historical Distortions in Costume Dramas.” China Youth Daily: China Youth Online, July 19, 2018. http://news.sina.cn.

六成受访者反感古装剧篡改历史,中国青年报·中青在线记者 王品芝 实习生 陈子祎 ,news.sina.cn ,2018年07月19日。

2. Zhang, B. “The 'Ambition' of 'Serenade of Peaceful Joy' and the Dilemma of Historical Costume Dramas.” China News, May 13, 2020. http://www.chinanews.com.

《清平乐》的”野心”与古装历史剧的困局,张斌,上海大学上海电影学院教授,www.chinanews.com ,2020年05月13日。

3. Zhang, B. “The 'Ambition' of 'Serenade of Peaceful Joy' and the Dilemma of Historical Costume Dramas.” China News, May 13, 2020. http://www.chinanews.com.

《清平乐》的“野心”与古装历史剧的困局,张斌,上海大学上海电影学院教授,www.chinanews.com ,2020年05月13日。

4. Tang, S. “From Costume Drama to Historical Drama: A Critique of 'The Qin Empire'.” Douban Movie, December 1, 2020. https://movie.douban.com/review/13025329/.

从古装剧走向历史剧,唐山 评论 大秦赋 ,https://movie.douban.com/review/13025329/, 2020年12月01日。

5. Sun, S. L. Research on Ancient Chinese Historical Drama. Nanjing: Nanjing Normal University Press, 2004.

孙书磊 著 《中国古代历史剧研究》 南京师范大学出版社出版 ,2004年7月1日。

6. Zhou, C., ed. “Experts Discuss 'The Rebel Princess': Historical Costume Dramas Need Refined Approaches and Cultural Depth.” Sina News, January 24, 2021. https://news.sina.com.cn.

专家研讨《上阳赋》:古装历史剧需有精品思路、文化质感,周驰,news.sina.com.cn,中国新闻网, 2021年01月24日(由中国传媒大学戏剧影视学院和中国电视艺术交流协会影视艺术专业委员会共同主办的电视剧《上阳赋》专家研讨会)。

7. Qin, X., and Zhang, M., eds. Ceramic Research and Social Reconstruction. Xi’an: Shaanxi Normal University Press, 2025.

《陶瓷研究与社会重建》,秦小丽 张萌 编著,陕西师范大学出版社,2025年1月。

8. National Museum of China, ed., and Zhang, Y., sub-ed. Research Series on Collections of the National Museum of China: Porcelain Volume (Song-Yuan). Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2023.

《中国国家博物馆馆藏文物研究丛书-瓷器卷(宋-元)》,中国国家博物馆 编 张燕 分卷主编,上海古籍出版社,2023年9月。

9. Fan, B. The Way of Becoming Vessels: The Art of Ceramic Forms from Prehistoric Times to the Song Dynasty - A Study on the Evolution of Chinese Ceramic Shapes and Styles from Qin-Han, Sui-Tang to Song Dynasties. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2021.

《成器之道:史前至宋的陶瓷造型艺术-秦汉隋唐两宋时期中国陶瓷器形与风格的演变历程研究-造型纹饰釉色-陶瓷的艺术-宋代五大名瓷》,范勃 著,生活读书新知三联书店,2021年10月。

10. Ma, W. The Patterns of Porcelain. Beijing: Forbidden City Publishing House, 2013.

《瓷之纹》,马未都 著,故宫出版社,2013年9月。

11. Liu, T. New Notes on Song Porcelain. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2022.

《新编宋瓷笔记》,刘涛 著,生活读书新知三联书店,2022年6月。

12. Ma, W. The Colors of Porcelain. Beijing: Forbidden City Publishing House, 2011.

《瓷之色》,马未都 著,故宫出版社,2011年5月.

Author Contribution

Zhen Zhou was the lead writer, Xiaoyun Ma sorted out materials and proofread translation.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Author Biographies

- Zhen Hou is a faculty member in the Department of Public Art at Jiangnan University, specializing in material aesthetics, cultural creative design, and traditional craftsmanship. Her work has been recognized with multiple national honors, including awards from the National Art Exhibitions and extensive support from the National Arts Fund. She also served as Image and Landscape Manager for the Beijing Olympics, receiving commendations for her contributions.

- Xiaoyun Ma, a teacher at Jiangnan University’s School of Foreign Languages, focuses on English teaching and translation. She has received numerous national and provincial awards for teaching excellence and served as chief editor of the textbook General English for Interpretation and Translation.

One might speculate whether the dominant glaze colors of Song porcelain subtly align with the four directional totems of Chinese cosmology—the Azure Dragon (east), White Tiger (west), Vermilion Bird (south), and Black Tortoise (north)—symbolized by green, white, red, and black? If so, this resonance would further indicate the continuity of Chinese culture.

Literary Gathering and Spring Banquet Scroll illustrate the lifestyle of elite scholar-officials, while Along the River during the Qingming Festival presents a panorama of commoners’ daily existence. The refined leisure culture permeating Song society did not derive utterly from material wealth, but rather emerged as a top-down cultural phenomenon rooted in philosophical alignment with naturalness.

In Along the River during the Qingming Festival, there is a multitude of figures, events, settings, and scenes. Through those people, happenings, and objects, one can glimpse the prosperity of Bianliang (Kaifeng) and witness an orderly microcosm of society.