Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Incorporation of Wandering Knights into Han Stone Reliefs as Cultural Symbols

- The Two Types and Manifestations of Wandering Knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

- The Political Symbolic Significance of the Wanderer Knights’ Image in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

- Conclusion

- Author Contribution

- Funding

- Acknowledgments

- Conflicts of Interest

- Author Biographies

- References and Notes

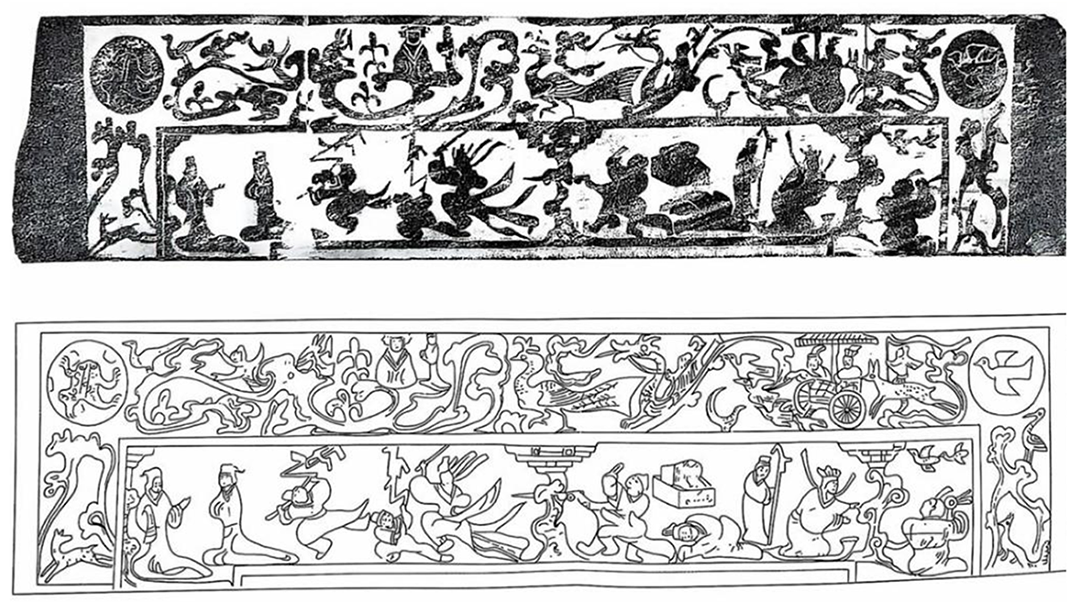

On the second floor of the left stone chamber of the Wuliang Shrine, the stone relief titled Mastiff Bites Zhao Dun adopts an instantaneous narrative composition to depict the dramatic moment when Duke Ling of Jin (晋灵公, 624–607 BC) releases a mastiff to attack Zhao Dun. The scene vividly portrays the mastiff leaping toward Zhao Dun, Zhao Dun dodging the assault, and Ling Zhe rushing forward to shield Zhao Dun, raising his foot to fend off the attacking dog. On the right side of the screen, there is a title that runs through the upper and lower boundaries of the stone relief, separating the image space of different story Stone Reliefs and explaining the content shown in the stone relief with words.

The title of a stone relief, as a directly related textual material, is of great help in interpreting the content of the image. Moreover, the story narrated by the title and the language used in the narrative have extremely high value in verifying the actual transmission of the story in the Han Dynasty. The inscription at the right end of the stone relief constructs a temporal flow within the image space, facilitating a more immediate establishment of narrative time and space. This enhances the vividness of the storytelling while maximizing its narrative function within the spatial constraints of the composition.

The image of the story of Orphans of the Zhao Family in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs is also one of the themes of wandering knights rescuing vulnerable people. The story of Orphans of the Zhao Family was first recorded in detail in the Records of the Grand Historian: The Zhao Family (《史记·赵世家》). The Records of the Grand Historian records that the difficulties faced by the Zhao family began with the rebellion of Tu Angu (屠岸贾). Tu Angu was favored by Duke Ling of Jin and Duke Jing of Jin (晋景公). He became a Jin Sikou (晋司寇) [4].

As the official in charge of the prison, Tu Angu overturned old accounts and framed Zhao Dun for the death of Jin Linggong. Tu Angu insisted on punishing the Zhao Dun family for regicide. Han Jue (韩厥) attempted to dissuade Tu Angu but failed, and later informed Zhao Shuo (赵朔). Zhao Shuo did not flee and entrusted the sacrificial rites of the Zhao clan to Han Juehou. He held onto his righteousness and waited for Tu Angu to cause chaos. Tu Angu launched the rebellion of Xiagong without authorization and exterminated the Zhao family. However, Zhao Shuo’s wife, Cheng gong’s elder sister (成公姊), still had a posthumous child and fled to hide in the Jin Palace. At a critical moment, Zhao Shuo’s disciple, Gongsun Chujiu, and Zhao Shuo’s friend, Cheng Ying, saved the Zhao family from danger, leaving behind the heroic and glorious story of the Orphans of the Zhao Family. Gongsun Chujiu (公孙杵臼) and Cheng Ying are chivalrous individuals who genuinely befriend Zhao Shuo. They did not leave due to the destruction of the Zhao family, nor did they commit suicide out of loyalty due to the death of their lord. Instead, with their independent individual will and values that transcend life, they assessed the situation and chose to rescue the Orphans of the Zhao Family in a more difficult way to achieve the spirit of chivalry.

The stone relief of the Orphans of the Zhao Family, depicted on a Wu liang Shrine stone that was scattered overseas during the Republic of China, has a clear and complete story title (Figure 7). Stone relief adopts an instant narrative image composition method. In the picture, the woman sitting in a baby gown is Zhao Shuo’s wife, and the baby in her arms is Zhao Shuo’s son. After the downfall of the palace, Zhao Shuo’s wife, relying on her identity as the elder sister of Jin Chenggong, escaped to the palace and gave birth to Zhao Wu (赵武), the only bloodline of the Zhao family. Tu Angu wiped out everything and broke into the palace to search for the orphan Zhao. After the orphan of Zhao escaped the search of Tu Angu, Zhao Shuo’s retainer, Gongsun Chujiu, and Zhao Shuo’s friend Cheng Ying (程婴) decided to adopt a diversion scheme to hide someone else’s baby in the mountains as a substitute for Zhao Gu. Gongsun Chujiu died alongside the fake orphan.

Symbolism of Political and Power Discourse: A Study of the Wandering Knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

by Cunming Zhu * , Xinying Xia

School of Literature, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2025, 3(1), 16-34; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2025.0618a10

Received: March 5, 2025 | Accepted: May 10, 2025 | Published: June 18, 2025

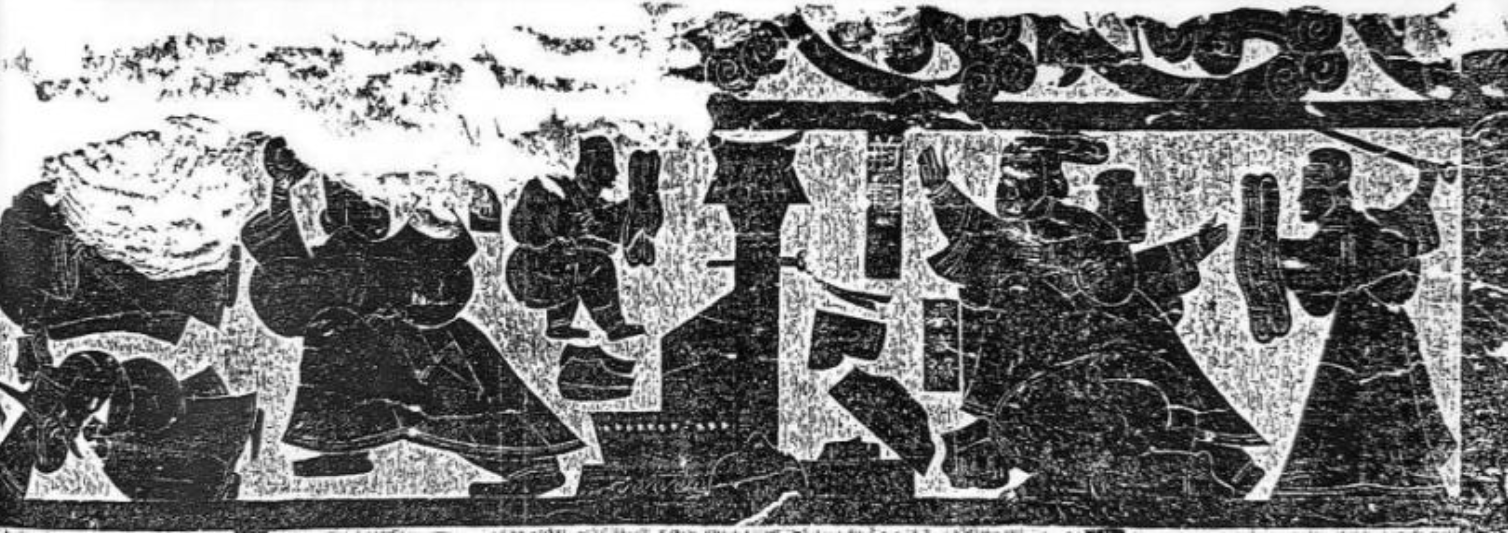

In the wall paintings of the Han tombs in Yinan, Shandong Province, there is a painting that combines the image of Lin Xiangru holding a Bi, Meng Ben (孟贲), a warrior of the Qin state, and two peaches on a high footed container from the story of Killing Three Scholars With Two Peaches (二桃杀三士) in the same picture space. Whether intentionally designed or unintentionally wrong, it can be seen that Lin Xiangru is a brave and martial image in the impression of the Han people (Figure 3).

Introduction

Among the character designs in the Han Dynasty stone reliefs, a prominent image is that of the wandering knights (游侠), depicting famous historical stories of chivalry. These types of images of wandering knights have become first-hand materials for studying the culture of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty in China and can provide insight into the historical and cultural changes of that time through the analysis of their visual characteristics.

Sima Qian (司马迁) was the first to include the figure of the ranger in official historiography, granting it cultural recognition in the Records of the Grand Historian: Biographies of wandering knights (《史记·游侠列传》). This led to a cultural transformation of the ranger in history. The formal establishment of the culture of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty not only had a profound impact on the Han Dynasty, but also on the entire Chinese culture. The images of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs are a key to unlocking the culture of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty. Through these visual representations, we can appreciate the presence of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty, grasp the pulse of wandering knights’ culture, and understand the plastic art and social culture of the Han Dynasty.

2.2. Images of Wandering Knights Rescue Stories in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

The Han Dynasty Stone relief images depicting the story of a ranger rescuing members of the Zhao family include scenes such as The Mastiff Bites Zhao Dun and The Orphan of the Zhao Family. Both narratives reflect the chivalrous spirit of the ranger, who sacrifices his life in a heroic effort to save the Zhao lineage.

The story of Mastiff Bites Zhao Dun, also known as the story of Lingluo Rescuing Zhao Dun (灵辄救赵盾), roughly follows the plot of a foolish king of Jin who plans to kill the wise minister Zhao Dun. Duke Ling of Jin invites Zhao Dun to a banquet and sends soldiers to ambush him, attempting to induce him to behave beyond propriety and frame him. However, Zhao Dun’s carriage driver, Ling Luo (灵辄), was aware of the conspiracy and secretly remained by Zhao Dun’s side to protect him. When Duke Ling of Jin was about to frame Zhao Dun, he exposed the conspiracy. Jin Linggong’s plan failed, and he was furious. He let the dog bite Zhao Dun, who was about to leave, and fought the evil dog with his spirit to protect Zhao Dun and rescue him from danger. Afterwards, Zhao Dun learned that the driver who saved the person was a hungry man who had received food and alms under the mulberry tree back then. Five images of the story A Mastiff Bites Zhao Dun in the Han Dynasty stone carvings have been discovered so far. The image of a dog leaping into the air and biting people is the iconic image of the story of a mastiff biting Zhao Dun. The image of the story of a mastiff biting Zhao Dun from the left stone chamber of the Wuliang Shrine features a detailed list of titles, providing us with both graphic and textual references for interpreting the image (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

2.1. The Image of a Ranger Fighting Against a Hero in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

The depictions of chivalrous warriors opposing kings in the Han Dynasty stone reliefs primarily portray stories from the pre-Qin era, featuring knights who assassinate or resist tyrannical rulers. These narratives encompass a wide range of story types, reflecting the diverse expressions of chivalric resistance in early Chinese history. However, among these stories, only the depictions of Jing Ke Assassinating the Qin King and Returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State appear in significant numbers, with their visual representations having developed into standardized and recognizable patterns. Other images of chivalrous resistance stories with clear title markings are only depicted in the Stone Relief of Wu liang Shrine (武梁祠) in Jiaxiang (嘉祥), Shandong Province.

The story image of Jing Ke Assassins the King of Qin is a representative image of the hero’s resistance story in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs. Among the numerous historical stories and images of Han Stone Reliefs, the story of Jing Ke’s assassination of King Qin is widely distributed and presented in a patterned composition. Most Han Dynasty stone relief depictions of the story of Jing Ke’s assassination of the King of Qin share a consistent compositional style. These images compress events from multiple moments into a single visual frame, breaking away from chronological narrative logic and instead employing spatial narrative techniques to highlight the dramatic climax of Jing Ke’s assassination attempt.

In the stone reliefs of the Wu family cemetery and Shrine in Jia xiang, Shandong Province, three images depicting the story of Jing Ke’s rebellion against the King of Qin were found. These images share highly similar content, and two of them are accompanied by written inscriptions. Taking as an example the image of Jing Ke assassinating the King of Qin on the west side of the small niche on the back wall of the stone chamber in front of the Wuliang Shrine in Shandong Province, one can appreciate this episode image in the Han Stone reliefs (Figure 1).

The central pillar in the scene represents the interior of the Qin Dynasty’s Xianyang Palace (咸阳宫), where the story unfolds. The first group of images depicts Qin Wuyang (秦舞阳) and the unsealed header letter, illustrating the events prior to Jing Ke’s assassination attempt on the Qin king. Jing Ke and Qin Wuyang have just entered the palace, and the king is initially examining the letter presented by Fan Yuqi. Qin Wuyang, overwhelmed by the pressure of the mission, appears fearful and trembling, arousing suspicion among the Qin officials. To prevent the plot from being uncovered, Jing Ke calmly offers an apology and explanation to the king, easing doubts and allowing the assassination attempt to continue. Notably, in the bottom right corner of the pillar, a box containing a severed head symbolizes the letter delivered to the King of Qin by Fan Yuqi. The box is half-open, indicating that the King of Qin has already read the letter. To the right of the headscarf, a figure kneels and prostrates, identified by the inscription as Qin Wuyang. The scene shows only Qin Wuyang crawling on the ground in fear, deliberately omitting Jing Ke’s calm and composed demeanor, which serves to explain and excuse Qin Wuyang’s fearful behavior.

The second set of images features a severed sleeve above the headscarf, a circular sword hilt with an unsheathed scabbard held in one hand on the left side of the pillar, the fleeing figure of the King of Qin on one side, a pair of shoes placed in front of the throne, and a courtier lying on the ground behind the King of Qin. These visual elements collectively depict the dramatic moment in the story when Jing Ke draws a dagger concealed within the map and attempts to assassinate the King of Qin. The severed sleeves, the image of the fleeing king of Qin, and the panicked waiters and courtiers around him all depict the intensity of the assassination scene.

The third set of images depicts Jing Ke being restrained while bravely resisting, representing the next stage of the assassination narrative: the King of Qin’s attendant physician, Xia Wu Ju (夏无且), subdued Jing Ke using a medicine bag, enabling the King of Qin to draw his sword and slash Jing Ke’s thigh. The fourth set of images presents a dagger embedded in a pillar and a guard armed with a sword and shield, illustrating the final act of the assassination attempt. Though severely wounded, Jing Ke made a last attempt to strike the King of Qin with his dagger, but missed, and the dagger lodged into a bronze pillar. The King of Qin retaliated by stabbing Jing Ke, inflicting eight wounds. Realizing the failure of his mission, Jing Ke leaned against the pillar and burst into laughter. Despite his injuries, he extended his broken leg and cursed the King, expressing his unwavering intent to assassinate him. At that moment, palace guards arrived and killed Jing Ke.

Through the above analysis, it can be seen that the Stone relief of Jing Ke assassinating the King of Qin places iconic objects that occurred at different times in the same image space to form a narrative stone relief that marks the complete plot of the story. This collaborative composition separates the chronological sequence of events, breaking the linear logic of time. It compresses occurrences from different moments—both before and after the climax—into a single visual space, using spatial logic to narrate the story. This narrative technique vividly captures the heroic deeds and courageous struggle of Jing Ke in his attempt to assassinate the King of Qin. Jing Ke’s bravery and chivalric spirit, along with the righteous resolve of figures such as Tian Guang, Gao Jianli, and Yan Dan—though absent from the image—are spiritually embedded in the composition. Their presence is conveyed through the cultural symbolism of chivalry, imbuing the portrayal of Jing Ke with a profound sense of moral vitality and cultural resonance.

The other is the story image of the Han Dynasty stone reliefs, Returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State. Lin Xiangru (蔺相如) was a famous civil servant of the State of Zhao. Historical records show that initially, Lin Xiangru was a servant of Zhao’s eunuch Miao Xian (缪贤), possessing both literary and military skills. It can be inferred that Lin Xiangru’s background was that of a wandering scholar or adventurer. The story of Returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State is a turning point for Lin Xiangru to become a famous minister of Zhao, and a typical embodiment of Lin Xiangru’s loyalty, righteousness, trustworthiness, intelligence, courage, and fearlessness as a chivalrous spirit and cultural character. Lin Xiangru was recommended to the King of Zhao to provide advice on the matter of the national treasure of Zhao, the jade bi. Lin Xiangru brought the jade into Qin, and with his intelligence, courage, and justice, retrieved the precious jade of Zhao from the greedy king of Qin. He returned the jade intact to Zhao, which not only preserved the jade but also protected Zhao from Qin’s attack.

In the Han Dynasty stone reliefs, the story of Jiang Xiangru, which can reflect Lin Xiangru’s civil servant status and humble and tolerant qualities, is not selected; only the story of Returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State, which highlights Lin Xiangru’s brave martial arts spirit, is seen. Moreover, in the Han Dynasty paintings, Lin Xiangru is only depicted as a brave warrior holding up a jade bi to resist the king of Qin (Figure 2).

3.The Political Symbolic Significance of the Wanderer Knights’ Image in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

The historical story of Stone Reliefs in the Han Dynasty. Stone Reliefs have established a lasting tradition of Chinese visual storytelling. The historical stories and images of wandering knights are also part of it. Behind the historical stories and images of the wandering knights, there is a social change that is both a cultural memory of history and a cultural product that adapts to the moral and political requirements of the new era. Through the images of the stories of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs, we can have a glimpse of the social, political, and cultural landscape of the Han Dynasty, manifested in two aspects.

3.1. The Ranger Became a Hero Against the Qin

The images of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs, with a large number, wide distribution, and patterned composition, are the story images of Jing Ke Conquers the King of Qin and Lin Xiangru Returns to Zhao in Perfect Harmony. This indicates the widespread and popularized nature of the two types of chivalrous stories and images in Han society. These two images of the ranger’s story reflect the theme of the ranger’s resistance against Qin.

From the content of the image story, it can be seen that the narrative of Jing Ke’s assassination of the King of Qin and Lin Xiangru’s return to Zhao is a historical story of Qin’s hegemony before Qin’s unification. It is a silhouette of Qin’s military conquest and oppression of the six states, reproducing the bloody and tearful history of the six states in the Warring States period being swallowed up by the strong Qin, and highlighting the heroic deeds of resisting the strong Qin. In addition, there is an image of Zhang Liang assassinating the King of Qin (张良椎秦王) carved on the Gaoyi Que in Ya’an, Sichuan. The encounter between Qin Shi Huang, the King of Qin, and Zhang Liangzhi—a loyal martyr from one of the former Six States—during Qin Shi Huang’s eastern tour after political unification, is a significant historical event. This episode reflects the anti-Qin sentiment among the people under the Qin Dynasty’s political unification through a vivid and representative historical narrative.

In terms of visual representation, the images of the ranger and the king of Qin form a binary opposition and contrast of strength and weakness. The image of the ranger is just and brave, while that of the king, either fleeing in panic or begging for mercy, shows ugliness and immorality.

The stone relief of the story of the ranger resisting Qin reshapes the image of the ranger and that of the king in the narrative of the image. The portrayal of the King of Qin in the Han Dynasty visual narratives evokes deep-rooted anti-Qin sentiments within the collective memory of the public. These depictions weave a shared consciousness centered on resisting Qin tyranny and serve to construct a new form of political identity rooted in the Han Dynasty ideology. By reshaping the image of the ranger as a moral exemplar aligned with orthodox Confucian values, the Han narrative further dissolves the inherent conflict between the ranger and royal authority. Through the frequent depiction of anti-Qin stories featuring rangers, these figures are elevated to the status of national heroes who opposed Qin despotism and are strategically employed as vehicles for disseminating Han political consciousness.

Conclusion

The art of stone reliefs in the Han Dynasty inherited the traditional imagery of pre-Qin Chinese culture and created a new world of imagery under new circumstances, with almost all-encompassing connotations. The worldview of Han Dynasty people was presented through the symbolic symbols of patterns and images in artistic design, which became a manifestation of the aesthetic spirit of Deep sinking and majestic (深沉雄大) and Powerful (强悍) in the Han Dynasty. The historical story Stone Reliefs of the Han Dynasty’s knights-errant is an example of this spirit. Through analysis, we find that the historical Stone Reliefs of the Han Dynasty’s knights errant reflect a change in the spirit of the Han Dynasty, and behind the change is the symbolic value of the political discourse of the Han Dynasty’s royal power.

The Han Dynasty established the pattern of ordinary people becoming generals or prime ministers (布衣将相之局), marking the end of the ancient aristocratic society and the beginning of the era of unification. The four people, society dominated by scholars, workers, peasants, and merchants, became the main social structure of the Han Dynasty’s unified society. In the requirements of the new era, the cultural barriers between the elite cultural circle and the folk cultural circle have disappeared, and communication and interaction between central and local cultures have become frequent. The historical stories and images of the Han Dynasty’s image of the wandering knights record the cultural changes of the Han Dynasty’s wandering knights entering the orthodox cultural circle in a cultural form and becoming tools for political education of the monarchy, reflecting the political and cultural strategies used by the political rulers in the era of Han Dynasty’s unification. The spiritual heritage of the ranger culture pioneered in the Han Dynasty became a symbolic form influenced by political and power discourse at that time.

After the Han Dynasty, the culture of wandering knights in China has been continuously replicated and recreated throughout the ages. No matter how it changes, we have found its source of vitality through the study of graphics and textual relationships in the Han Dynasty stone art.

1. The Incorporation of Wandering Knights into Han Stone Reliefs as Cultural Symbols

Since the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, wandering knights have been suppressed and marginalized by royal authorities. As a marginalized social group that often stood in opposition to political authority, the question of why wandering knights were depicted and even praised in the Han Dynasty stone reliefs has become a significant topic in the study of Han Dynasty art and visual culture. The official historical records of the Han Dynasty included a dedicated biography for knights-errant, and their emergence as a prominent theme in the Han Dynasty stone reliefs suggest that the status and perception of knights-errant underwent significant transformation during this period. These societal changes in the Han Dynasty played a crucial role in shaping the artistic representation of chivalry in Han imagery.

At the beginning of Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian: Biographies of wandering knights, he quotes a Legalist thinker from the pre-Qin period. Who commented on wandering knights:” Confucian scholars use literature to violate laws, while knight warriors use force to violate prohibitions” [1]. From modern research on the culture of wandering knights, we know that during the pre-Qin period, chivalrous knights were considered as a social group that acted through the use of force, which was a defining characteristic of chivalric behavior. During the pre-Qin period, wandering knights were regarded as criminals who disrupted authoritarian rule and were the social targets of political attacks by royal authority. Han Fei’s remarks indirectly proved that at that time, the wandering knights (a social group), with a social influence comparable to that of Confucian intellectuals, could oppose royal authorities.

In Han Feizi’s critique of the chivalrous community, chivalrous individuals are described as practicing benevolence and righteousness, thereby gaining credibility among the common people while remaining distant from royal politics. The public appreciates and even imitates the behavior of wandering knights, forming a social custom of respecting chivalry and righteousness. Although Han Feizi regarded wandering knights and Confucian scholars as similar in that both disrupted monarchical rule, wandering knights were, in fact, practitioners of the Confucian ideals of benevolence and righteousness (仁义). Sima Qian observed that prior to the Qin and Han dynasties, Confucianism, Mohism, and Legalism all maintained an exclusionary stance toward wandering knights. This suggests that the folk martial arts culture to which the wandering knights belonged stood in opposition to the elite intellectual traditions represented by Confucianism, Mohism, and Legalism. In the Western Han Dynasty, there were changes in society, and we need to re-examine the culture of chivalry.

With the advent of tit focused Dynasty and the historical process of establishing a unified society, the rulers of the Han Dynasty, having drawn lessons from the Qin state’s downfall due to its tyranny, focused on constructing a stable Han imperial culture. Cultural exchanges between the central and local governments became increasingly frequent. As a historian, Sima Qian stood at the forefront of the changing times. He transcended the political biases of his time, challenged the attitude of pre-Qin intellectuals toward the chivalrous spirit of the wandering knights, and recognized the moral and cultural value embodied by the wandering knights. Sima Qian pointed out that although the behavior of wandering knights does not align with political education, they possess many commendable qualities such as honesty and trustworthiness, decisiveness in action, a willingness to sacrifice for righteousness, fearlessness in the face of danger, and humility in not flaunting their abilities or achievements [2].

From the portrayal of Lin Xiangru in the Han Dynasty stone carvings, it can be seen that he existed as a brave martial arts warrior in the historical memory of the Han people. In the eyes of Han Dynasty people, Lin Xiangru was a historical ranger with the spirit and cultural character of a ranger.

There are as many as 15 images of Lin Xiangru returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State (蔺相如完璧归赵). They are distributed in Shandong Province, Northern Shaanxi, and Sichuan, forming a certain pattern in the image representation. The image of a warrior holding up a jade became a symbol of the story image of Lin Xiangru returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State. In the Wuliang Shrine in Shandong Province, there is a picture depicting the story of Returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State, with a written inscription (Figure 2). The stone relief depicts three characters: Lin Xiangru, the King of Qin, and the courtiers behind the King of Qin, who hold a jade bi high above their heads beside a pillar. The pillar separates the King of Qin and Lin Xiangru into two spaces, forming an opposing spatial situation. The pillar also functions as an inscription, bearing the title: “Lin Xiangru, an official of the Zhao State, presenting the He-shi Jade to Qin (蔺相如赵臣也奉璧于秦).” This image employs a momentary narrative to capture the moment when Lin Xiangru raises a jade bi to resist the Qin king and is about to collide with the jade bi against a pillar, sacrificing for righteousness. The most representative moment in the climax plot of this story is used to depict the story of Lin Xiangru returning the He-shi Jade intact to the Zhao State.

Sima Qian criticized the false benevolence and righteousness established in society based on social status and fame and praised the chivalrous spirit of the wandering knights in plain clothes who were able to uphold their faith and sacrifice their lives to practice morality even in poverty and ordinariness. In Sima Qian’s view, the wandering man in plain clothes is the one who truly possesses morality. In Sima Qian’s cultural interpretation of the ranger, the ranger became a practitioner of righteousness in Confucianism.

In the Records of the Grand Historian: Biographies of wandering knights, Sima Qian expressed regret that the Clothed Knights (布衣游侠) in civil society had not received the attention they deserved. He noted that if their deeds were not recorded and promoted, they would be lost in the long river of history. As a pioneer of Chinese historiography, Sima Qian recorded the life stories of famous clothed wandering knights Zhu Jia, Ju Meng, and Guo Jie in the Western Han Dynasty, and truthfully documented the prevalent social customs of chivalry and righteousness in Han society. This influenced the compilation of historical books in the Han Dynasty.

Also, Ban Gu’s work Biographies of the Wandering Knights in the Book of Han (《汉书·游侠列传》) recorded the deeds of some wandering knights, such as Zhu Jia (朱家), Ju Meng (据孟), Guo Jie (郭解), Wan Zhang (万章), Lou Hu (楼护), Chen Zun (陈遵), and Yuan She (原涉). We can see that in the unified social order of the Han Dynasty, the living space of the wandering knights was increasingly suppressed by the royal power, and official culture spread from the central to the local level. The wandering knights showed a trend of moral and bureaucratic evolution. The virtuous gentleman-wanderer became a new form of wanderer created by the unified society of the Han Dynasty. The cross-class networking of wandering knights in plain clothes with nobles and generals was a strategy for seeking survival space in the early Han Dynasty, and a precursor to the bureaucratization of wandering knights in the later period. The active integration of the wandering knights into the political system of the monarchy and their role as both officials and heroes became an important path for them to integrate into the Han dynasty court.

The moralization and bureaucratization of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty were the result of the Han Dynasty’s unified political system and the mainstream Confucian ideology that suppressed, invaded, and transformed the cultural order of folk society. This process marked the integration of wandering knights from the margins into the mainstream of Han society, ultimately leading to the dissolution and disappearance of their original form. Of course, during the Han Dynasty, the wandering knights consciously transformed themselves by integrating into the political order of the Han Dynasty, embracing mainstream ideas, and assimilating into the political culture of the Han Dynasty monarchy. At the same time, they brought the culture of wandering knights from folk society into the field of royal political culture, promoting the exchange of cultural traditions between the central and local governments.

Sima Qian’s discovery and refinement of the spirit and culture of chivalry were based on his observation of the folk culture of the Han Dynasty, which revered chivalry and righteousness. He broke down the barriers between pre-Qin elite culture and martial arts culture. He re-examined chivalry through the lens of Han Confucian ideology and culture, discovering and shaping a chivalrous spirit that integrated Confucian moral values with the external use of force characteristic of chivalry.

The creation of the spirit and culture of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty was a product of the exchange and integration of elite culture and folk cultural traditions in Han society. The creation of the spirit and culture of chivalry in the Han Dynasty led to the acceptance of chivalry from a cultural perspective in orthodox culture. This later transformed chivalry into a tool for the political education of the monarchy, leveraging the profound foundation of chivalry culture in folk society. The transformation of the cultural identity of wandering knights during the Han Dynasty created the conditions for their inclusion in Han stone relief imagery. As Han’s paintings were deeply infused with the cultural beliefs of the time, they had ample justification for incorporating the theme of wandering knights.

2. The Two Types and Manifestations of Wandering Knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs

Once the spirit and culture of chivalry were accepted by the official culture during the Han Dynasty, wandering knights became eligible to enter the historical image system of the Han Dynasty. However, while the official culture of the Han Dynasty paid attention to and accepted the spirit of chivalry, the spiritual culture of chivalry was also transformed by the official political and religious system of the Han Dynasty. The selection of themes, representation, and distribution of images of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Relief reflect both the dissemination of the spirit and culture of the wandering knights in Han society and the official construction of that culture by the Han authorities.

The militaristic nature of the wandering knights’ actions during the Han Dynasty, combined with their spiritual commitment to the principle of Justice (义), laid the foundation for their entry into the visual culture of the Han era. In Han Stone Reliefs, the images of wandering knights are typically represented through historical narrative scenes. These stories and depictions are largely set in the pre-Qin period and are documented in the Han Dynasty classics and historical texts. Zhang Yanyuan’s Records of Famous Paintings of Various Dynasties (《历代名画记》) states: “The exquisite of paintings dates back to the Qin and Han dynasties (图画之妙,爰自秦汉).” During the Han Dynasty, Emperor Ming of Han (28-75) was very fond of painting and even set up a studio specifically for it. He also founded Hongdu Academy to collect the wonderful art of the empire (汉明雅好丹青,别开画室。又创立鸿都学,以集奇异,天下之艺云集)” [3].

The Eastern Han Dynasty established official institutions dedicated to drawing and cartography. Painting during this period primarily focused on historical narratives, transforming the symbolic language of these stories into visual imagery. By disseminating Confucian historical tales through art, the state aimed to educate the populace and reinforce its ideological and political authority. The stories of the pre-Qin wandering knights recorded in the Han Dynasty’s classics and history were filtered and visualized by the ruling class and elite cultural circles of the Eastern Han Dynasty and then spread to the folk society from top to bottom through the official release of historical stories and illustrations.

There are more than 40 historical stories and images of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs with clear textual titles and fixed patterns. The more famous ones include Jing Ke Assassinating the Qin King (荆轲刺秦王), Returned the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State (完璧归赵), Orphans of the Zhao Family (赵氏孤儿), The Mastiff Bites Zhao Dun (獒咬赵盾), Nie Zheng’s assassination of Han, Yao Li’s assassination of Qingji, specialized assassination of Wu Wang Liao, Yu Rang’s assassination of Zhao Xiangzi, and Cao Mo’s robbery of Duke Huan of Qi. According to the number of images, regional distribution, and spatial distribution of stone reliefs, areas influenced by Confucian culture are more common.

The images of wandering knights in Han Stone Reliefs can be divided into two types: images of wandering knights fighting against each other and stories of wandering knights rescuing each other.

In the Shenmu Tomb of the Eastern Han Dynasty in Shaanxi Province, the story of Jing Ke’s assassination of the King of Qin and the story of Lin Xiangru’s perfect return to Zhao are both depicted on the stone carvings of the tomb lintel. The exaggerated movements of the characters in the picture create a strong dynamic, and the opposing composition of the ranger and King of Qin centered on twisted pillars creates tension. The heroic and righteous spirit of chivalry and courage to resist is filled in the images (Figure 4). From the image selection and engraving of this door lintel stone, the story of Lin Xiangru Returning the He-shi Jade Intact to the Zhao State and the story of Jing Ke’s assassination of the king of Qin are depicted on the door lintel as images with the same theme and style. It can be seen that during the Han Dynasty, people regarded Lin Xiangru and Jing Ke as the same type of people, both chivalrous and fearless wandering knights.

Abstract

The Han Dynasty was an important period in the development of traditional Chinese society, and Han Stone Reliefs are epic images of Han society. By studying images from the Han Dynasty, historians can use visual evidence to support historical claims. The emergence of the Han-painted ranger image is a product of the social and cultural changes of the Han Dynasty, reflecting the political and cultural transformations brought about by the unification of the Han Dynasty. The image of the Han-painted ranger holds symbolic significance in the political and power discourse of the Han Dynasty. Through specific analysis, it becomes evident that the culture of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty was a product of the interaction and integration between official and folk cultures. This cultural dynamic provided the foundation for the inclusion of wandering knights as a theme in Han Stone Reliefs. The article categorizes the images of knight-errant stories in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs into two types: one depicting acts of resistance, and the other portraying heroic rescues. These two themes reflect how the image of the knights-errant in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs became a unique symbol within the political discourse of Han Dynasty power. Through the study of the ranger image in the Han Dynasty stone reliefs, this paper reveals that these reliefs, as an art form, vividly express the aesthetics and values of the Han Dynasty through their image design. When applied to the artistic form of Han Dynasty stone reliefs, this artistic expression is realized through the narrative function of imagery.

Edited by: Eloise

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Cunming Zhu, and Xinying Xia, "Symbolism of Political and Power Discourse: A Study of the Wandering Knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs." JACAC 3, no.1 (2025): 16-34.

AMA Style

Zhu CM, Xia XY. Symbolism of Political and Power Discourse: A Study of the Wandering Knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs. JACAC. 2025; 3(1): 16-34.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References and Notes

1. Han Feizi’s Five Worms. Commentary by Gao Huaping et al. Beijing: Commercial Press, 2016, 747.

《韩非子·五蠹》,高华平等评注,北京:商务印书馆,2016年版,第747页。

2. Sima Qian (Han Dynasty). Records of the Grand Historian: Biographies of Wandering Knights. Compiled by Pei Yin variorum (Song Dynasty), with annotations by Sima Zhen (Tang Dynasty) and Zhang Shoujie (Tang Dynasty). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2000, 2413.

(汉)司马迁撰:《史记·游侠列传》,(宋)裴骃集解,(唐)司马贞索隐,(唐)张守节正义,北京:中华书局,2000年版,第2413页。

3. Zhang Yanyuan (Tang Dynasty). Records of Famous Paintings of Various Dynasties. With accompanying annotations. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, 2023, 15, 17.

(唐)张彦远:《历代名画记》,承载译注,上海:上海古籍出版社,2023年版,第15、17页。

4. Sikou was the official in charge of criminal justice in ancient China.

司寇是中国古代主管刑狱的官员

5. It refers to the person who was starving to death under the shade of mulberry trees, later metaphorically described as a story of seeking gratitude and repaying kindness.

指的是“饿死在桑树荫下的人”,后来比喻为寻求知恩图报的故事

6. Zhou Yuanbin. Confucian Ethics and the Narrative of the Spring and Autumn Period. Jinan: Qilu Book Society, 2008, 1.

周远斌著:《儒家伦理与<春秋>叙事》,济南:齐鲁书社,2008年版,第1页。

7. Zhou Yuanbin. Confucian Ethics and the Narrative of the Spring and Autumn Period. Jinan: Qilu Book Society, 2008, 74.

周远斌著:《儒家伦理与<春秋>叙事》,济南:齐鲁书社,2008年版,第74页。

8. “Governing Principle of the Han Dynasty”was the governing philosophy of the Han Dynasty. Chen Suzhen pointed out that” Governing Principle of the Han Dynasty" and” Spring and Autumn Annals" are two important concepts in the history of the Han Dynasty. The Confucian study of the Spring and Autumn Annals was an important theoretical basis for the rulers of the Han Dynasty to determine the” Governing Principle of the Han Dynasty". See Chen Suzhen. Spring and Autumn Annals and the Han Way: A Study of Politics and Political Culture in the Two Han Dynasties. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2023.

“汉道”是汉朝的治国之道。陈苏镇指出:“汉道”和《春秋》是汉代历史中的两个重要概念。儒家之《春秋》学是汉朝统治者确定“汉道”的重要理论依据。见陈苏镇:《<春秋>与“汉道”:两汉政治与政治文化研究》,北京:中华书局,2023年版。

9. Cai Qiling.” Discussing Classics from the Perspective of Image Studies: The Spring and Autumn Significance of Shandong Stone Relief Stories.” Image History, no. 1 (2020): 175–194.

蔡奇玲:《从图像学论经学——山东画像石故事的春秋大义》,《形象史学》2020年第1期,第175-194页。

Author Contribution

Cunming Zhu is the guide for the conceptualization of the paper, presenting important academic arguments, providing writing outlines, and providing information. Xinying Xia assists in collecting materials and writing the initial draft, while Cunming Zhu is responsible for revising the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Fund Major Project “Compilation and Overseas Communication Research of the Department of Sinology” (No. 14ZDB029).

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Author Biographies

- Cunming Zhu, Professor at the School of Literature, Jiangsu Normal University, Dean of the Institute of Chinese Culture Research, and Vice President of the Chinese Han Painting Society.

- Xinying Xia, a Master’s student at the School of Literature, Jiangsu Normal University.

Cheng Ying disguised herself as a person who abandoned righteousness and was greedy for profit, betraying the orphan of the Zhao family in order to obtain her daughter. Tu Angu believed Cheng Ying’s words and led the army under Cheng Ying’s guidance to eliminate Gongsun Chujiu hiding in the mountains and the fake Zhao Gu he guarded. Chujiu and Cheng Ying enacted a dramatic confrontation between loyal protectors and treacherous traitors before the oblivious generals. Ultimately, both Gongsun Chujiu and the impostor Zhao Gu met brutal deaths. Gongsun Chujiu increased the persuasiveness of the packet adjustment meter with his life and blood. Cheng Ying and Chujiu successfully convinced the generals that the last bloodline of the Zhao family had also been killed, and the Zhao family had been destroyed.

Afterwards, Cheng Ying hid in the deep mountains with the orphan Zhao and took on the responsibility of raising him. The plot of the story of the orphan Zhao in the Han stone relief is the same as that described in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian: The Zhao Family, providing a strong basis for the identification and research of the Han stone relief of the Orphans of the Zhao Family.

3.2. The Gentleman Who Compares His Virtues to the Zhao Family, Establishing the “Governing Principle of the Han Dynasty” (汉道)

In the historical stories of the Han Dynasty, Stone Reliefs of wandering knights, the Stone Reliefs of the Zhao family (赵氏家族) include the person who was starving under the shade of mulberry trees (桑下饿人) [5]. Mastiff biting Zhao Dun, Orphan of the Zhao family, Yu Rang stabbing Zhao Xiangzi(豫让刺赵襄子), and Lin Xiangru returning the He-shi Jade intact to the Zhao State.

Moreover, among the numerous vassal states of the pre-Qin period, the Zhao State stands out as the only one systematically and extensively represented in the Han Dynasty pictorial art. Whether in literary records, the textual titles inscribed on Han Stone Reliefs, or within the visual narratives themselves, wandering knights consistently serve as vital supporting figures. From the content of these depictions—whether directly portraying the benevolence and righteousness of figures like Zhao Dun and Zhao Xiangzi or emphasizing the moral virtues of the Zhao lineage through the life-sacrificing assistance of wandering knights—Han Stone Reliefs construct a distinctly positive image of the Zhao family. These visual narratives not only affirm the Zhao clan’s historical role in practicing benevolent governance and aligning with the Mandate of Heaven, but also symbolically link the family’s legacy to the eventual establishment of the Jin Dynasty. The recurring visual commemoration of the Zhao family in the Han Dynasty stone reliefs reflects the Han Dynasty’s ideological admiration and deliberate promotion of the Zhao family’s moral and political legacy.

In the relevant records of the Spring-Autumn Annals (《春秋》), Zhao Dun and other Zhao family figures are praised for their benevolence, righteousness, and cultivation of virtue, while the Jin royal family is ridiculed for their lack of virtue and deviation from the Tao. It is explained that the Zhao family’s adherence to the concept of the mandate of heaven and virtue, and the achievement of the Zhao State in accordance with the will of heaven, are the fundamental principles of royal mandate. Some scholars believe that “Confucius was the first person to combine Confucian ethics with narrative” [6]. The Spring-Autumn Annals is Confucius’ final masterpiece, expressing Confucian political thought. The narrative of the Spring-Autumn Annals has had a profound impact on later generations. The governing principle of the King (王道) is a unique perspective of Confucius’ narration in the Spring-Autumn Annals [7]. The way of the King is an ideal political and social state conceived by intellectuals represented by Confucianism during the Spring-Autumn and Warring-States periods (战国时期). It is based on the history of the three ancient dynasties. The establishment of Stone Reliefs depicting the stories of the Zhao family reflects the political principles of royal power constructed by Confucianism for the Han Empire during the Han Dynasty.

Since Emperor Wu of Han revered Confucianism, Confucianism has become the center of the political stage of the Han Dynasty, exerting a profound influence on the political culture of the Han Dynasty. The Confucian scholars of the Han Dynasty, based on Confucian classics and integrating the theories of the pre-Qin philosophers and folk cultural concepts, created the Governing principle of the Han Dynasty [8] for the Han Dynasty. It had a strict system and profound social belief foundation, including the correspondence between heaven and man, the mandate of heaven and the way of kings, and the rule of propriety, righteousness, and virtue. The three schools of Confucianism in the Han Dynasty’s Spring-Autumn Annals coexisted on the political stage of the two Han dynasties, forming a situation of coexistence and interaction among the three schools. The Spring and Autumn Annals, a classic of Confucianism, developed into an important theoretical basis for the political culture of the Han Dynasty through the pioneering interpretations of Confucian scholars.

During the Eastern Han Dynasty, Confucian scholars would select and organize stories from the Spring and Autumn Annals that were in line with political ideology. They would use history to pass on the classics and images to convey history, specifically demonstrating the Three Cardinal Guides and Five Constant Virtues (三纲五常) and other moral values. They adapted them to the cultural needs of political ideology. Some scholars believe that the study of the Spring and Autumn Annals during the Western Han Dynasty attained a prominent position. The historical story themes in the Han Dynasty stone carvings were conveyed through images carved by stonemasons, and historical events were depicted through scenes and character images to educate the people and promote the profound meaning of Confucius’ Spring -Autumn Annals [9].

The story of the Zhao family recorded in the Spring and Autumn Annals is not only a historical fact based on the original scriptures, but also a concrete example embodied in the Confucian classic political doctrine of rule by virtue. The story of the Zhao family during the pre-Qin period has a similar nature to the establishment of the Han Dynasty by the Liu family, transcending social hierarchy and establishing a new country. It is rooted in the historical traditional stories of the Kanto Region, represented by Zhao, and has a certain cultural soil. Therefore, the story of the Zhao family during the pre-Qin period has high utilization value for the construction of the political culture of the Han Dynasty. It is an inevitable choice for the official formulation and release of historical story images.

The historical stories of the Zhao family selected for the Han Stone Reliefs are all stories of the main characters of each generation of the Zhao family, such as Zhao Dun, Zhao Shuo, Zhao Xiangzi, and the stories of repaying kindness and making chivalrous friends with ordinary wandering knights. The Han Dynasty demonstrated the benevolence and virtue of the Zhao family through the cross-class interactions of its ancestors. Through the portrayal of wandering heroes who were detached from politics and who sacrificed their lives to protect the Zhao family in times of danger, the natural talent of the Zhao family was vividly portrayed.

From the visual narrative of the series of Zhao family story Stone Reliefs that are related before and after, it can be understood that Zhao was appointed by Heaven (天) and obtained the King Order (王命) due to his benevolence, righteousness, and virtue. And the chivalrous group formed between the Zhao family and the chivalrous heroes depicted in the Zhao family’s story stone relief shares similar characteristics and founding experiences with the Liu Bang group, which established the Great Han Dynasty, the series of stories about the Zhao family in the historical stories of the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs of wandering knights. In the concepts of Mandate of Heaven (天命) and Rule of Virtue (德治) and other Governing principles of the Han Dynasty, there is a cross-temporal confirmation with the Han family.

The excavation and development of the story of the Zhao family originating from the Spring —Autumn Annals by the rulers of the Han Dynasty is a means of cultivating virtue, comparing the Han family to the Zhao family to confirm the political concept of royal power in the Han Dynasty, and metaphorically implying that the establishment of the Han Dynasty by the Han family was the legitimate royal order of Shunde Chengtian. While educating the people on morality, propriety, and righteousness, it also consolidated the orthodox position of the Han Dynasty from the perspective of ideology and culture. The stone relief of the Zhao family is a product of the Han Dynasty’s construction and dissemination of political ideology; it is a manifestation of the political culture dominated by Confucianism in the Han Dynasty.

Through the exploration of the political symbolic significance of the images of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty Stone Reliefs, we find that these stories of wandering knights are symbols of the operation of political discourse in the Han Dynasty royal power. In the process of transforming historical stories of wandering knights into images with social and educational significance, they have been further transformed and constructed by political rulers, becoming a tool for spreading political ideology. The stories of wandering knights in the Han Dynasty were accepted by the orthodox culture of the Han Dynasty, but criticism and suppression of the wandering knight social group still existed from a political standpoint. The rulers of the Han Dynasty accepted the spirit and culture of chivalry not by changing their political stance, but by adopting an open and inclusive cultural attitude. They accepted the culture of chivalry and gained the power to construct the spiritual culture of chivalry in the Han Dynasty. As a result, they incorporated the folk martial arts culture that had always been in opposition to official culture into the camp of official orthodox culture, further controlling local culture in the Han Dynasty.