Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Avian Motifs as Auspicious Patterns: Historical Context and Typology

- The Production and Reproduction of Bird Motifs as Classical Symbols

- Inheritance and Contemporary Application of Classic Avian Motifs as Cultural Symbols

- Conclusion

- Author Contribution

- Funding

- Acknowledgments

- Conflicts of Interest

- Author Biographies

- References and Notes

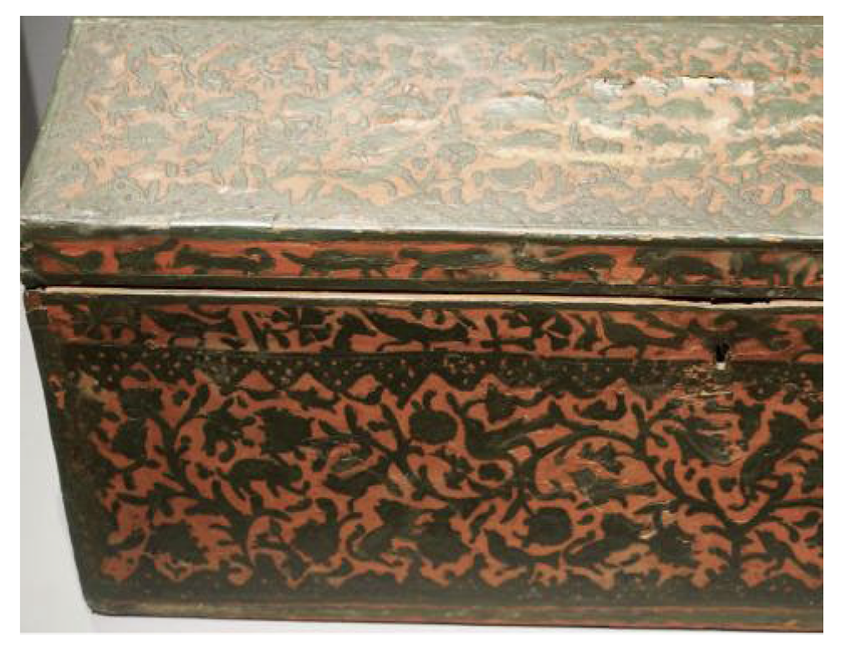

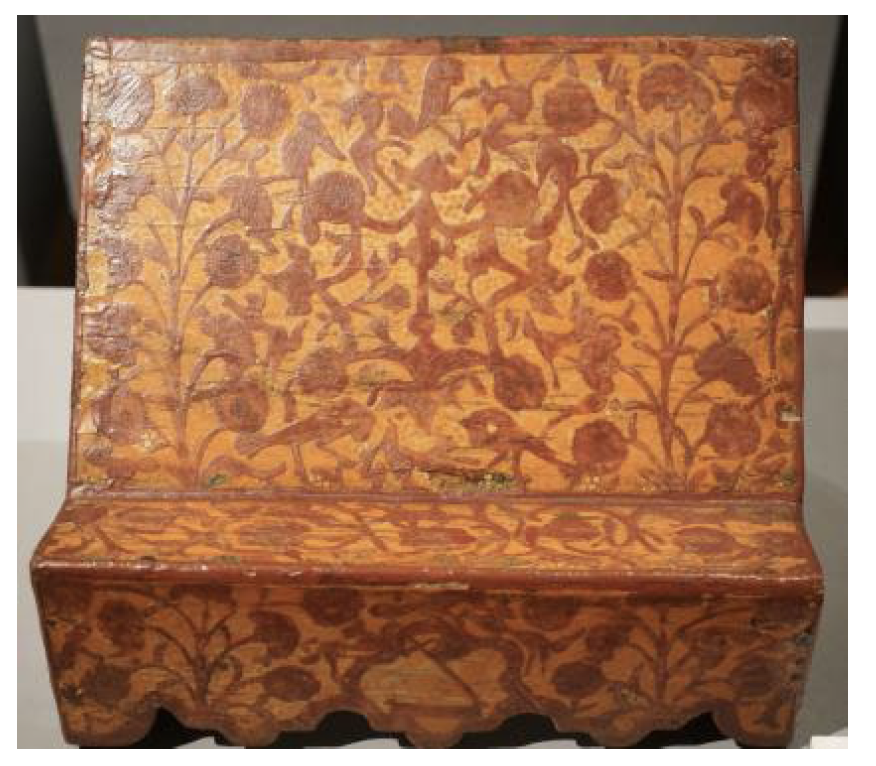

The avian motifs of Talavera pottery influenced lacquerware production in New Spain as early as the 18th century. A red-patterned bookshelf-like artifact and a red-ground lacquerware piece housed in the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City both employ flat silhouette effects, combining birds with plants and covering the entire surface with dense patterns. This decorative style persisted into the 20th century, as seen in another lacquer plate where the same flat bird-and-plant composition reappears, enhanced by four colors for a richer visual impact. Beyond lacquerware, birds frequently adorn Mexico’s folk art Árbol de la Vida (Tree of Life). The Tree of Life is said to derive from ancient Maya traditions, with forms inspired by biblical narratives, folktales, or popular culture.

4.2. Application of Classic Avian Motifs in Modern Design

The Mexican case demonstrates that, upon entering pre-modern society, Chinese visual imagery directly or indirectly contributed to Mexico’s self-identity construction. This identity-building process is embedded in visual cultural heritage and reemerges as a classic element in modern design.

Mexico’s modern design evolution paralleled its national awakening and ongoing identity affirmation. By the 1960s, postmodernist trends—decentralization, rejection of grand narratives, and cultural diversity—gained global traction, influencing both Mexico and the United States. Following the 1846–1848 Mexican-American War, ten southern U.S. states (originally Mexican territories) were ceded, resulting in Mexico losing nearly 55% of its land. Mexican-Americans in these states retained strong cultural ties to their Latin roots, fostering a nostalgic demand that reshaped Mexico’s folk art market.

Since the 1960s, Otomi embroidery from the Sierra Madre Oriental mountains in central Hidalgo, Mexico, gained popularity in the U.S., spurring an embroidery industry led by local women. Drawing liberally from historical visual resources, these artisans selectively adopted motifs favored by the U.S. market. Classic avian motifs, deeply rooted in Mexican tradition through centuries of cultural exchange, blurred their origins—whether pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican or Chinese-influenced ceramics. Vibrantly colored birds rendered with lively, slightly archaic stylization satisfied American romanticized perceptions of Mexico while fueling the embroidery sector’s growth. These embroideries became ubiquitous in interior soft furnishings, emerging as quintessential Mexican design elements.

From Auspicious Patterns to Classical Symbols: The Production and Diffusion of Chinese Bird Motifs in Mexican Folk Art

by Fan Liu * , Huamin Wang

School of Art and Design, Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2025, 3(1), 1-15; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2025.0406a9

Received: January 28, 2025 | Accepted: March 8, 2025 | Published: April 6, 2025

3.4.2. Technical Disparities

Chinese phoenix motifs emphasize the interplay of line and plane, employing gongbi techniques with cobalt underglaze. A concentrated “outline blue” (fenshui) pigment was first applied to trace contours, followed by diluted washes to fill color zones, creating layered decorative depth—a hallmark of mid-Ming Dynasty innovations. The porcelain body, fired at ~1300°C, achieved a dense, translucent white substrate with optimal glaze-body integration.

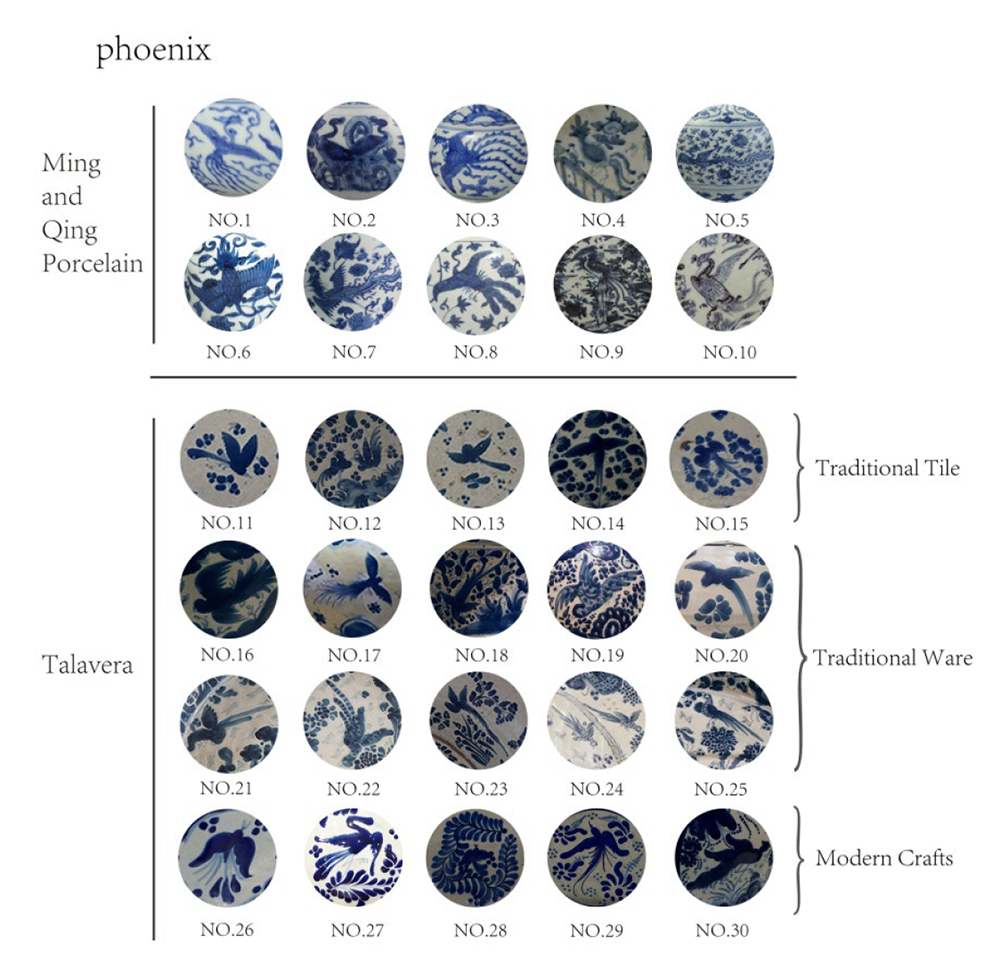

Talavera artisans, however, utilized two methods: a Spanish-derived impasto technique and a Chinese-inspired flat-wash imitation. During the 17th–18th centuries, flat washes dominated avian designs (e.g., Nos. 11–25), with limited tonal variation reserved for larger basins (Nos. 19, 22, 24–25). Post-19th century, the impasto method gained prominence, with a thick, high-viscosity glaze applied onto a pre-glazed base, and fixed through high-temperature firing to create relief-like effects (Nos. 26–28, 30).

3.4.3. Divergent Stylistic Expressions

Among the Ming-Qing phoenix motifs (Nos. 1–10), only Nos. 4, 9, and 10 were produced in Zhangzhou, while the others originated from Jingdezhen. The phoenixes from Zhangzhou kilns are depicted in a standing posture, unlike the soaring postures typical of Jingdezhen phoenixes. Zhangzhou ware features more unrestrained brushwork and a rustic style, with darker blue-and-white glazing tones and less white, lustrous ceramic bodies compared to Jingdezhen porcelain.

In terms of phoenix representation, the S-shaped necks and backward-turned heads emphasize their gracefulness, while the tall crowns symbolize imperial dignity, and the flowing tails convey aristocratic elegance. In contrast, Talavera birds lack the long, slender necks seen in Chinese phoenixes. Their wings are spread wide, suggesting vigorous flight and lightness of posture. The tails vary in length and number—sometimes three, four, or even one or two feathers—depending on compositional needs or the potter’s artistic intuition. When depicting flight, Talavera birds are shown either from a top-down perspective (e.g., Nos. 14, 15, 16, 18, 21, 26, 27, 29) or at eye level (e.g., Nos. 11, 12, 13, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 28, 30). The birds’ heads connect directly to their bodies without the elongated, elegant necks characteristic of Chinese phoenixes; instead, their beaks are minimally outlined with lines or color blocks. Regarding glaze aesthetics, Talavera potters valued deeper shades of blue, considering darker tones superior.

A comparative analysis of avian motifs in Chinese porcelain and Talavera pottery reveals how Chinese bird designs were influenced by New Spanish indigenous aesthetics. The rustic indigenous style merged with the dynamic fluidity of Chinese avian forms, echoing Echavarría’s assertion that the Baroque style underwent unique development in the Americas. It was practiced by Indigenous peoples and other New Spanish social groups, who reinterpreted and blended New World themes, ultimately forming a mestizo aesthetic that redefined cultural identity.

3.1. The Cognitive Role of Avian Motifs in Ceramic Design

Avian motifs, among the most prevalent decorative patterns in Talavera pottery, exhibit striking similarities to the phoenix and crane motifs in Chinese visual culture, suggesting a high probability of emulation of Chinese avian iconography. Within the Chinese visual cultural system, avian motifs possess three semiotic characteristics: representation, object, and interpretant. For ceramic artisans in the New World, however, the semantic depth underlying these Chinese motifs—beyond their representational and cognitive functions—likely remained inaccessible. Nevertheless, the morphological resemblance between the Chinese phoenix and the Resplendent Quetzal, a species indigenous to New Spain, may have fostered a sense of cultural familiarity among Puebla artisans. In Aztec and Maya civilizations, the Resplendent Quetzal was revered as an embodiment of Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent deity), symbolizing agricultural abundance and climatic harmony [11].

Although guild regulations restricted the production of Talavera ceramics exclusively to Spanish artisans, the demand for indigenous labor in Puebla’s construction projects and urban development necessitated interaction between the two populations. Indigenous workers, often employed as day laborers or low-wage auxiliary staff, likely contributed to and influenced the design of avian motifs through their participation in peripheral production processes.

Although the pre-Hispanic indigenous representation of Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent deity) combined serpentine forms with Resplendent Quetzal (Pharomachrus mocinno) iconography, this iconic imagery was systematically erased following Spanish colonization. The colonizers sought to establish a new visual lexicon to supplant pre-Columbian civilizations. Consequently, the phoenix motifs prevalent in Chinese porcelain, which bore morphological parallels to Mesoamerican avian symbolism, became the primary reference for Spanish artisans in Puebla. For indigenous laborers, this hybridized motif served as a mnemonic surrogate—omitting the serpent’s head and stylized decorative elements while merging the naturalistic depiction of the Resplendent Quetzal with the Chinese phoenix’s artistic conventions. In doing so, it created a symbolic alternative rooted in cultural memory.

During the adaptation of Chinese blue-and-white phoenix motifs, the divine connotations of the Resplendent Quetzal were seamlessly integrated with the formal aesthetics of Chinese phoenix imagery in Talavera’s avian designs. This synthesis led to the proliferation of bird motifs across utilitarian vessels (jars, plates, basins) and architectural tiles. Notably, even the 250-year-old Talavera Uriarte workshop, which claims to uphold traditional craftsmanship, identifies avian motifs as quintessential symbols of its heritage. In essence, Talavera’s avian iconography functions as a replication of dominant worldviews and sociopolitical orders, revealing an inextricable interplay between material function, objecthood, cultural value, and civilizational paradigms.

3.2. The Communicative Function of Avian Motifs

Building upon their cognitive engagement with avian iconography, Puebla ceramic artisans reinterpreted and adapted crane motifs derived from Chinese prototypes, infusing them with localized cultural understanding. Through this process, the circulation of auspicious motifs generated novel iconographic contexts. Mexico is home to two crane species: the Sandhill Crane (Antigone canadensis) and the Whooping Crane (Grus americana). Unlike raptors, which held central symbolic roles in Mesoamerican cosmovision, cranes occupied an ambiguous position in indigenous Mexican symbolism. Nevertheless, as a native species, cranes were likely familiar to local populations. Under Spanish colonial restrictions, which prohibited direct representation of Aztec emblems such as the eagle perched on a cactus (a symbol of Tenochtitlan’s founding myth), Puebla artisans found creative recourse. The crane standing on shoushan stone (a motif from Chinese porcelain) may have provided a symbolic bridge—its formal resemblance to the forbidden Aztec eagle motif allowed artisans to subtly transpose cultural meanings.

The Aztec eagle, emblematic of the promised land of Aztlán and Tenochtitlan, mirrors the posture of the heraldic eagle in the Codex Mendoza, which symbolizes New Spain’s imperial authority. In contrast, the crane in Chinese iconography represents an otherworldly avian spirit associated with utopian landscapes. While indigenous and mestizo artisans likely lacked full comprehension of the Chinese crane’s semantic nuances, they strategically conflated its form with indigenous avian symbolism. This synthesis enabled the construction of hybrid identities within the constraints of colonial iconographic policies.

Even as the Spanish dismantled indigenous traditions and imposed a new visual regime, cultural symbols such as Quetzalcoatl (the Feathered Serpent deity) and the eagle (cuauhtli) persisted as deeply embedded metaphors within Indigenous consciousness. This symbolic resonance facilitated the appropriation of avian motifs from Chinese porcelain, which were reinterpreted and assimilated into Talavera pottery as Sinicized avian iconography.

3.3. The Role of Avian Motifs in Social Stratification

During the colonial period, affluent urban residents treated Chinese imported ceramics as luxury items. In rural settings, ranchers, estate owners, or their managers could afford some of these goods. International trade provided access to expensive tableware and decorative objects for those with purchasing power. Even cheaply produced and aesthetically inferior goods were shipped to Mexico to cater to consumers obsessed with exotic Asian porcelain. Consequently, the integration of rural agricultural and mining semi-peripheral regions into the modern world economy of merchant capitalism was successful. Compared to core urban centers, living conditions in rural areas distant from the capital of New Spain were harsh. A comparison of the typological and formal variability of rural assemblages with those of Mexico City reveals austerity features in all peripheral regions. Nevertheless, imported ceramics were employed as prestige markers and displays of social status and cosmopolitan taste.

Chinese porcelain provided artisans worldwide with a visual and aesthetic language. Mexican consumers and artisans appropriated patterns from Chinese porcelain, adapting them to local customs and culture while modifying the forms and motifs based on Chinese prototypes [12]. Art historian Gustavo Curiel interprets the Mexican adoption of Chinese aesthetics as “proposing alternative interpretations of an imagined East Asia while drawing on local Mexican imagery, architecture, flora, and fauna. Thus, Mexican artists infused their own reality into the process of imitation [13].” Among contemporary Latin American scholars, there is the reluctance to acknowledge Talavera’s appropriation of traditional Chinese auspicious motifs. Instead, they argue that colonial artisans inherited and developed Chinese ceramic patterns, integrating their own traditions and interpretations. In the reproduction of avian motifs as classical symbols, the exotic imagery signifying noble identity was re-excavated, re-extended, and re-refined. This process of cultural re-production also served to demarcate social hierarchies.

Introduction

The relationship between auspicious patterns and classic symbols is complex and closely intertwined, forming an essential part of visual culture and folk art. Auspicious patterns have evolved from nature worship and totemic beliefs into a symbolic system that integrates natural themes with rich cultural connotations. They serve as a means for people to interpret and represent the world, embodying cultural heritage in material form.

Since the lifting of trade restrictions during the Longqing period, Chinese blue-and-white porcelain was exported to Latin America via Manila galleons. Auspicious Chinese motifs, exemplified by bird patterns, were continuously adopted and reinterpreted by local folk artists across various media and time periods, eventually becoming iconic symbols of Mexican tradition. However, in some Latin American countries, the colonial period is perceived as a history of humiliation, marked by oppression and despotism that both preceded colonization and persisted in modern nation-states. As a result, there is a general reluctance to acknowledge this historical period, as it is often associated with Europe's collective guilt [1]. Consequently, this history, which is closely related to Chinese arts and crafts, has been briefly summarized in Latin America as merely an influence from the East.

In China, research on this history has been limited to fields such as world trade history and maritime exchange history. From the perspective of a shared future for humanity, studying the production and dissemination of Chinese auspicious patterns in Mexico and their role in shaping Mexican identity holds practical significance in enhancing cultural confidence and advancing cultural diplomacy.

3.4. Indigenous Aesthetic Preferences in the Reproduction of Avian Motifs

The exotic appeal and opulent stylistic eccentricities of Chinese porcelain were assimilated by indigenous peoples and other New Spanish social groups, forming a mode of cultural appropriation that redefined hybrid identities—a phenomenon scholars term the Mexican Baroque. While the transpacific trade between New Spain and China played a pivotal role in shaping colonial aesthetics and local identity formation, this dimension has been overlooked in prior domestic and international scholarship. Equally neglected is the question of who consumed Talavera ware from Puebla. According to historical records, approximately 1.86 million Spaniards settled in the Americas between 1492 and 1832, with 250,000 migrating in the 16th century and the majority arriving in the 18th century under Bourbon immigration incentives [14]. By 1570, around 100,000 Europeans governed over 10 million indigenous peoples. After five centuries of intermarriage and mestizaje, meta-analyses by scholars such as Rodríguez-Moura reveal contemporary genetic admixture in Mexico City and southern Mexico as 31% European, 6% African, and 62% indigenous [15]. Thus, the Hispanic population in New Spain constituted a minority, with most inhabitants being mestizo (mixed Spanish, Indigenous, and African descent). Talavera ceramics predominantly served the daily and architectural needs of Hispanic and mestizo classes, inevitably embedding local consumers’ habits and aesthetic sensibilities into the designs. A comparative analysis of phoenix motifs reveals distinct aesthetic divergences between the two traditions.

3.4.1. Divergence in Stylistic Approaches

(Figure 1) In Chinese examples (Nos. 3, 5–8), phoenix feathers are meticulously delineated with individualized brushstrokes, achieving a state of “no coloring without outlining” (wu ran bu gou), akin to traditional Chinese meticulous painting (gongbi). Notably, No. 10 exhibits polychromatic feather gradations rendered with precision. In contrast, Talavera avian motifs lack detailed articulation, relying instead on color blocks and silhouettes rather than the Chinese technique of outlining followed by flat washes.

4. Inheritance and Contemporary Application of Classic Avian Motifs as Cultural Symbols

Over the two centuries following the end of colonial rule in Mexico, and particularly under today’s globalized context, critical questions emerge: How can cultures maintain their autonomy? How can daily life be organized according to indigenous logic rather than the frameworks imposed by Spanish or American value systems? How can societies address the continuity of identity amid discontinuous historical development, while seeking contemporary expressions of modernity within visual language systems? Classic avian motifs provide a visual paradigm for addressing these questions.

4.1. Cross-Media Dissemination of Classic Avian Motifs

Puebla’s blue-and-white pottery, aligned with the Mexican government’s promoted aesthetic tastes, stands as a quintessential legacy of Mesoamerica’s colonial history. International collectors also recognize Talavera as one of Mexico’s most compelling artisanal traditions. On December 8, 2019, UNESCO inscribed Talavera craftsmanship into the World Heritage List through two declarations: the Declaration of Craftsmanship for Talavera Pottery-Making in Puebla and Tlaxcala, Mexico and the Declaration of Ceramics from Talavera de la Reina and El Puente del Arzobispo, Spain.

Today, Talavera blue-and-white pottery from Puebla—Mexico’s renowned ceramic hub—is ubiquitous in markets across the country. During a visit to a leading Talavera workshop earlier this year, staff explained their commitment to preserving tradition (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6). This tradition encompasses both time-honored techniques [16] and classic motifs, among which avian designs dominate. The emphasis on avian symbolism is not unique to this workshop. In fact, since the early 20th century, contemporary ceramists dedicated to revitalizing Talavera traditions have consistently featured bird motifs as one of the most frequently recurring patterns in their works.

5. Conclusion

When examining China’s relationship with global history and reflecting on cultural identity, we often unwittingly adopt Western-centric narratives of subjectivity. We habitually begin from a “modern historical condition defined by the historicity and self-perception of others,” rather than from an unmediated tautology of “Chineseness.” In such analyses, the historicity of others can only be understood as the history of a subject, which, through this understanding, reveals itself not as external to us: The history of modern China is an integral part of world history. The future significance of ancient China depends solely on the extent to which we become subjects, rather than objects, of world history [17]. Within a world history dominated by Western subjectivity, the world is perceived as an internal system of economic, political, legal, and ideological values. This implies its ambition to subsume and ‘sublate’ all historically independent, self-contained civilizational systems, either eliminating them as anachronisms or absorbing them as localized nutrients into its own body [18]. Sino-Mexican cultural interactions exemplify precisely those elements targeted for elimination or assimilation.

Ancient Chinese civilization, evolving within a sociopolitical system oriented around its own historical trajectory—devoid of true rivals or external others—centered its self-understanding on empirical self-referentiality, never synchronizing with Western historical subjectivity. When forcibly integrated into this global historical framework, China’s indirect cultural interactions with the world were further marginalized by its peripheral position within Western historicity.

Re-examining transcultural exchanges under the Manila Galleon Trade through this historical lens, emphasizing the role of visual symbols and analyzing material interactions in image dissemination, constitutes a reality-based approach rooted in social existence. This methodology diverges from Western academia’s tendency to spiritualize practice, aligning more closely with Marxist materialist historical analysis. Its significance lies in forging value-based value identity and constructing a coherent narrative of historical continuity. Similarly, viewing Mexican cultural identity through this framework reveals complexities and contradictions far exceeding prior understandings. Re-entering this discourse, we recognize China’s value as a subject of world history: within Mexico’s visual language systems, it provides paradigmatic symbolic imagery for Mexicans to articulate contemporary expressions of modernity’s historical experience.

In this light, advancing research on the international dissemination of visual cultural heritage and revitalizing public awareness of China’s subjective narratives hold unique and critical value. These efforts strengthen the consciousness of the Chinese national community, enhance cultural soft power, facilitate cultural diplomacy, and contribute to building a culturally robust nation.

2. Avian Motifs as Auspicious Patterns: Historical Context and Typology

2.1. Classification and Evolution of Avian Motifs

From the dawn of civilization, humans created serialized visual symbols and generated a wealth of narrative and symbolic visual cultural practices through imagery to record, express, preserve, and disseminate information. As early as 7,000 years ago, artifacts engraved with dual-bird motifs emerged in the Hemudu culture. Jade objects and pottery adorned with avian patterns have also been unearthed from the Hongshan and Liangzhu cultures. The oracle bone script of the Shang and Zhou dynasties already featured the character “phoenix (凤).” During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods, avian motifs grew more vivid and dynamic. The Qin and Han dynasties infused these designs with fantastical and romantic elements. With the introduction of Buddhism in the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern dynasties, avian motifs began to intertwine with floral patterns. By the Song and Yuan dynasties, bird motifs had flourished as standardized auspicious patterns in folk art.

As early as the Tang Dynasty, the Changsha Kiln produced ceramics featuring lifelike depictions of egrets, swallows, luan birds (mythical phoenix-like creatures), wild geese, mandarin ducks, and red-crowned cranes. In traditional painting, bird-and-flower subjects matured during the Song Dynasty. The Xuanhe Painting Catalogue’s Discourse on Bird-and-Flower Painting emphasized the moral and ethical symbolism of such works, asserting that they “inspire viewers, evoking the sensation of being immersed in nature and gaining spiritual nourishment [2].” This philosophical shift influenced the rendering of avian motifs on ceramics. By the late Ming Dynasty, the demands of export trade profoundly altered porcelain styles, leading to a gradual simplification of decorative avian patterns and their evolution into stand-alone compositional motifs.

2.2. Common Bird Motifs in Export Blue and White Porcelain

There are many types of bird motifs in blue and white porcelain, including phoenix patterns, dragon-phoenix patterns, ribbon-tailed bird patterns, peony and peacock patterns, lotus and crane patterns, among others. Among these, the most frequently appearing motifs are the phoenix and the crane.

Since ancient times, the phoenix and the crane have been auspicious symbols in Chinese culture. With the increasing number of bird-and-flower painters during the Ming and Qing dynasties, these motifs were imbued with richer cultural and symbolic meanings. This reached its peak in the auspicious connotations associated with Ming and Qing porcelain [3]. By systematically categorizing and analyzing phoenix and crane motifs, one can observe the evolution of social culture and aesthetic preferences.

The phoenix motif is one of the most distinctive patterns in Chinese traditional culture, originally serving as a symbol of primitive totemic worship. Unlike the crane, the phoenix is a mythical bird invented within Chinese cultural traditions. The origins of the phoenix mainly stem from two theories: the Xuanniao (Dark Bird) totem theory and the Multicolored Auspicious Bird theory. These theories are derived from The Book of Songs – Shang Hymns – Xuanniao and The Classic of Mountains and Seas – The Southern Third Classic, respectively. As the king of all birds, the phoenix holds a highly prestigious cultural status.

Scholars have differing views on the emergence of the phoenix motif. Some researchers believe that it can be traced back to the patterns found on pottery from the Yangshao and Longshan cultures of the Neolithic period. The Qin and Han dynasties marked the peak of its development, during which the phoenix motif evolved from an exclusive element of aristocratic ritual vessels into an integral part of daily life. It was widely used in clothing, stone carvings, and architectural decorations such as eave tiles, often appearing alongside the dragon motif. During this period, its symbolic association shifted from male to female.

During the Wei, Jin, Sui, and Tang dynasties, the phoenix motif became further integrated into everyday life, symbolizing auspiciousness and prosperity. By the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, phoenix culture had evolved into a symbol of the imperial court. In particular, during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the phoenix became synonymous with the empress.

The formation of the crane motif in China has a long and rich history. Although scholars have not yet reached a consensus on its exact origins, the crane’s elegant form has made it a symbol of beauty and auspiciousness since ancient times. The earliest known depiction of a crane in China is a jade crane unearthed from the Tomb of Fu Hao at the Yin Ruins, dating back approximately 3,200 years. The earliest written record of cranes appears in Xiaoya – Heming (Lesser Odes – The Cry of the Crane), where cranes were already regarded as auspicious creatures symbolizing beauty and good fortune.

The development of crane culture reflects a coexistence of both popular and aristocratic influences, as well as a balance between spiritual symbolism and scientific understanding. Based on different symbolic meanings across historical periods, crane imagery can be categorized into three phases:

(A) The Immortal Symbolism Period (Qin and Han to Sui and Tang dynasties), where cranes were associated with Daoist immortality.

(B) The Auspicious and Prosperous Symbolism Period (Sui and Tang to Song and Yuan dynasties), during which cranes represented good fortune and noble character.

(C) The Longevity Symbolism Period (Ming and Qing dynasties to modern times), where cranes became an enduring emblem of longevity.

From the perspective of functional meaning, the evolution of crane imagery can be divided into three stages:

(A) The Naturalistic Stage, where cranes were depicted in their realistic forms.

(B) The Religious and Spiritual Stage, where they were associated with divine and mystical beliefs.(C) The Noble and Aristocratic Stage, where cranes symbolized purity, elegance, and elite status.

2.3. Production Characteristics of Bird Motifs

Understanding bird motifs as image symbols involves more than a simple relationship between signifier and signified. Their production process includes representation, object, and interpretation. Whether it is the phoenix, crane, swallow, or peacock motif, all bird imagery shares three essential characteristics.

2.3.1. Distinctive Features for Identification

Each bird motif possesses unique characteristics that distinguish it from other objects. Erya – Explanation of Birds describes the phoenix as having “the head of a rooster, the jaw of a swallow, the neck of a snake, the back of a tortoise, and the tail of a fish.” It is about six feet tall (approximately 1.82 meters) and exhibits brilliant colors. As a legendary divine bird, the phoenix embodies the traits of five different animals, setting it apart from real-world creatures. Similarly, the crane has highly recognizable features—long legs, a long neck, a long beak, a loud call, and an extended lifespan. These characteristics are prominently depicted in crane imagery.

2.3.2. Influence from the Object It Represents

Bird motifs are shaped by the attributes of the real or mythical birds they depict. Before the early Han dynasty, the phoenix was not distinguished by gender. The Classic of Mountains and Seas describes the phoenix as resembling an ordinary chicken, with a body covered in multicolored feathers. After the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern dynasties, the phoenix motif merged with the dragon motif and transformed from a male to a female symbol, with later representations emphasizing feminine characteristics. The crane, regarded as a symbol of immortality and purity, has always carried an aura of transcendence, which has become a defining aspect of its visual representation.

2.3.3. Cultural and Symbolic Significance

Bird motifs are also imbued with cultural, traditional, and social meanings. Over time, the phoenix has been endowed with four primary symbolic connotations:

(A) A guardian of prosperity and harmony, symbolizing favorable weather and auspicious blessings.

(B) A representation of imperial and aristocratic authority.

(C) A metaphor for virtue, righteousness, and moral excellence.

(D) A philosophical emblem of yin-yang balance and harmonious coexistence.

Similarly, the crane motif has evolved to carry rich symbolic meanings, primarily in four aspects:

(A) A symbol of perfection, rooted in prayers for divine protection and ideal fortune.

(B) A representation of immortality, derived from the pursuit of Daoist transcendence and longevity.

(C) A symbol of noble character, praising the virtues of humility, serenity, and integrity.

(D) A metaphor for political integrity, combining the above meanings to represent honesty, uprightness, and high moral standing in officialdom.

3. The Production and Reproduction of Bird Motifs as Classical Symbols

In the late Ming Dynasty, China monopolized the global ceramic market, with 80% of porcelain exports destined for Asia. Among these, approximately 60% were likely shipped to Manila in the Philippines and then transshipped to New Spain [4]. Early trade records between Manila and New Spain reveal that porcelain was a highly sought-after commodity among New Spanish clients from the very beginning [5]. Porcelain represents a cultural composite - a fusion of art and commodity that reflects the aesthetic tastes, cultural practices, and social mentalities of both its creators and purchasers. It combines daily utility, commerce, and artistry, serving simultaneously as functional products, profitable commodities, and treasured possessions. Porcelain became intertwined with long-distance trade, social customs, and elite sensibilities. It provides a unique and fascinating perspective for observing global interactions, revealing the commercial, technological, and intellectual exchanges facilitated through porcelain and its circulation.

Due to the high transportation costs of shipping porcelain from China to Mexico via the Manila Galleon, it became a symbol of wealth and social status. For the elites of New Spain, it was crucial to display their honor, prestige, and wealth through material culture and proper conduct [6].

Porcelain represented a connection to distant lands beyond the reach of most people. Compared to other ceramic wares, its high cost ensured that only a small fraction of the population could afford it, making it a marker of prestige and status [7]. This exclusivity inspired Spanish colonial potters in Mexico to imitate these ceramics and produce locally made-alternatives.

In 1521, in an effort to establish a purely Spanish city, the Spanish chose to build the city of Puebla in an area uninhabited by indigenous people. Historically, the region surrounding Puebla had been a center for pottery production, known especially for its fired red ceramics before the arrival of the Spanish.

In addition to its historical advantage in ceramic production, Puebla also had abundant resources such as clay, tin, lead, glass, and labor. Furthermore, during the early stages of the city's construction, there was a high demand for ceramic building materials. These factors collectively established Puebla as the center of ceramic production in New Spain.

Due to the localized production of tin-glazed pottery, Puebla's ceramic products had a significant price advantage. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Spanish ceramics cost two to three times more per crate than those from Puebla, while Chinese porcelain was approximately ten times more expensive per crate than Puebla's ceramics.

The imitation of Chinese porcelain in Puebla was most concentrated between the 17th and 19th centuries, a period known as the Oriental Style era. The guild of potters in Puebla even mandated in their ordinances that, the finest ceramics should imitate Chinese porcelain [8].

In 1630, Jesuit Bernabé Cobo reported that around this time, Puebla’s potters were producing ceramics that closely resembled Chinese porcelain in design. The influence of China can be observed in the adoption of Eastern shapes, the preference for blue-on-white decoration, and the increasing incorporation of Chinese motifs into colonial-era ceramics. Records of Talavera poblana ceramics provide evidence of this Chinese influence.

A revised ordinance in 1682 stipulated that the finest ceramics should imitate the blue of Chinese porcelain, maintaining the same style and blue glaze, except for black spots and colored backgrounds [9]. Clearly, the imitation and use of Chinese porcelain were officially sanctioned.

Scholars such as Agustín de Vetancourt argued that the Chinese ceramics imitated by Puebla’s potters were superior to those produced in Spain. The application of Chinese aesthetics by local artisans became a way for the colony to distinguish itself from the European metropole. It also demonstrated that colonial luxury goods did not have to rely on Spain: Luxury could be obtained from Asia, or its designs could be borrowed to produce luxury goods locally [10].

Abstract

Auspicious motifs evolved from nature worship and totemic beliefs into symbolically rich graphic signs that served cognitive, communicative, and social compartmentalization functions. Between 1573 and 1815, bird motifs from Chinese auspicious designs were introduced to Mexico through Chinese blue and white porcelain exported to the Americas. These motifs became associated with Mexican indigenous cultures, first appearing in the tin-glazed pottery of Talavera, Puebla. They were later widely used in native lacquerware, textiles, and other folk art, symbolizing nobility and exoticism. Over time, these motifs diverged from the cognitive and aesthetic interests of the Spanish patriarchal homeland, ultimately becoming folkloric symbols representing Mexican traditions and appearing in various contemporary Mexican folk artifacts.

Edited by: Eloise

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Fan Liu, and Huamin Wang, "From Auspicious Patterns to Classical Symbols: The Production and Diffusion of Chinese Bird Motifs in Mexican Folk Art." JACAC 3, no.1 (2025): 1-15.

AMA Style

Liu F, Wang HM. From Auspicious Patterns to Classical Symbols: The Production and Diffusion of Chinese Bird Motifs in Mexican Folk Art. JACAC. 2025; 3(1): 1-15.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References and Notes

1. Bailey, Gauvin Alexander. Art of Colonial Latin America. Translated by Jiang Shan. Changsha: Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, 2019: 4.

2. Pan, Yungao, ed. Xuanhe Painting Catalog. Hunan Fine Arts Publishing House, 2002: 310.

3. Zhao, Chunnuan. “Auspicious Birds and Beasts on Porcelain of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (Part I).” Chinese Ceramics 2 (2006): 75–77. DOI: 10.16521/j.cnki.issn.1001-9642.2006.02.025.

4. Nueva España (New Spain), established in 1521, was an important viceroyalty created by Spain in the American continent. It mainly covered Central America and parts of North America, including present-day Mexico, Central American countries, and the southwestern United States. As a core component of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, Nueva España was directly governed by the Spanish crown and exerted profound historical influences on the economy, culture, and politics of the Americas.

5. The earliest shipping record from 1592 contains a report about the cargo of the galleon San Felipe, which arrived at Acapulco on December 2, 1592. Its captain was Geronimo de Mendicabal from the Philippines. The “personal freight charges” section of the manifest recorded the quantity of ceramics carried. The ship also contained 900 pieces of ceramics belonging to another captain, Juan Bauptista Moroso. Other individuals had varying numbers of cajones or packages that might contain ceramics, but based on how they were listed, it remains unclear what exactly these packages contained or how many pieces were packed per bag. This method potentially allowed the export of goods exceeding permitted quantities. Indiferente Virreinal Caja 3504, Archivo General de la Nación, Expediente 36, 1731.

6. Zárate Toscano, V. “Los privilegios del nombre: Los nobles novohispanos a finales de la época colonial.” In El siglo XVIII: Entre tradición y cambio, edited by P. Gonzalbo Aizpuru, 325–356. México: El Colegio de México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2005.

7. Castillo Cárdenas, K. “La influencia de la porcelana oriental en la mayólica novohispana: su valor simbólico y su papel en la construcción de identidad.” In La nueva Nao: De Formosa a América Latina. Bicentenario del Nombramiento de Simón Bolívar como Libertador, edited by L. Chen, H.-C. Chen, and A. Saladino García, 41–61. Taipei: Tamkang University, 2013: 50-53.

8. Cervantes, E. A. Loza blanca y azulejo de Puebla. México: Tomo Primero, 1939.

9. McQuade, Margaret Connors. “Talavera Poblana: Cuatro siglos de producción y coleccionismo.” Mesoamérica 40 (2000): 118–140.

10. Meha Priyadarshini. Chinese Porcelain in Colonial Mexico: The Material Worlds of an Early Modern Trade. Springer International Publishing AG, 2018: 172.

11. Florescano, E. The Myth of Quetzalcoatl. Baltimore: JHU Press, 2002.

12. Liu, Fan, Du Zhang, and Qinyuan Tian. “The Chinese Style of Mexican Porcelain from the Perspective of the Maritime Silk Road in the 16th to 19th Centuries.” Art and Design Research 6 (2023): 13–17. DOI: CNKI:SUN:SHIZ.0.2023-06-012.

13. Curiel, Gustavo. “Perception of the Other and the Language of ‘Chinese Mimicry’ in the Decorative Arts of New Spain.” In Asia and Spanish America: Trans-pacific Artistic and Cultural Exchange, 1500-1850, edited by Donna Pierce and Ronald Otsuka, 30. Denver: Denver Art Museum, 2009.

14. Márquez, Rosario. La emigración española a América. 1995: 1765–1824.

15. Mexicanos para Niños. [EB/OL]. Accessed July 17, 2024. https://ninos.kiddle.co/Mexicanos

16. The production process of Talavera pottery consists of six steps, largely unchanged since the early viceregal period. This process may take three months, but for certain pieces, it can extend up to six months.

17. Zhang, Xudong. Cultural Identity in the Age of Globalization: A Historical Critique of Western Universalist Discourse. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2006: 5. DOI: 10.16521/j.cnki.issn.1001-9642.2006.02.025.

18. Zhang, Xudong. Cultural Identity in the Age of Globalization: A Historical Critique of Western Universalist Discourse. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2006: 19.

Author Contribution

Fan Liu: Conceptualization, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Huamin Wang: Data Curation, Visualization, Translation.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China under Grant Number 23BG113 for the project “The Spread and Influence of Chinese Porcelain in Mexico from the 16th to 19th Century.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks to SIENRA CHAVES, Sofia Elen, CARRERA, Arnulfo Allende, the Chinese Embassy in Mexico, and the Franz Mayer Museum for their help and support during the author's research trip to Mexico.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Author Biographies

- Fan Liu is a professor, doctoral tutor, and vice dean of the School of Art and Design, at Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, China. She is a member of the Teaching Steering Committee and Academic Committee of Wuhan Textile University and a special professor of “Sunshine Scholars.” She is in charge of the first-class public art and visual communication majors in Hubei Province, one of the first batch of excellent young talents in social sciences in Hubei Province, and an excellent young and middle-aged talent in literature and art in Hubei Literature Federation. She was a doctoral tutor at the Mexican Academy of Literature and Art, a visiting scholar at the Free University of Berlin, Germany, and a visiting professor at the University of Engineering Arts in Berlin. She is a member of the Chinese Artists Association, a member of the Chinese Literary Critics Association, and the vice president of the Hubei Chinese Clothing Culture Research Association.

Huamin Wang is a graduate student at the School of Art and Design, Wuhan Textile University, Wuhan, China. His research focuses on art theory.