Edited by: Sonia Song

Question 5: How is the auction situation?

In terms of auctions, Fenben (粉本) from the Dunhuang period are relatively rare, and if there is any outflow, the price is also extremely high. In 2004, a Dunhuang Fenben (粉本) was auctioned off with an estimated value of approximately 1.5 million yuan. Strictly speaking, the price of Fenben line manuscripts is higher than that of color manuscripts. The line draft is closest to the original work, while the later color draft has undergone secondary creation, deviating from the original artistic conception of Dunhuang and carrying personal emotions and cognition. Whether the artwork auctioned off at that time was personally painted by Zhang Daqian has also become a major point of controversy. Through existing publications related to Zhang Daqian, perhaps some clues can be found, as these publications provide detailed records of his situation during the Dunhuang period. The batch of Dunhuang Fenben (粉本) in the Lujiang Thatched Cottage (庐江草堂) collection has the most detailed color annotations. There are two theories about these works: One is that they were personally painted by Zhang Daqian, and the other is that they were painted by his disciples. The paintings from the Dunhuang period were not entirely created by Zhang Daqian but were funded by him, created by his team, and finally signed under Zhang Daqian’s name. [13]

The Taipei Palace Museum showcases a series of exquisite paintings from the Da Feng Tang Collection (大风堂藏画). The collections in Taiwan are easy to retrieve because of the existence of relevant publications since 1947. After Zhang Daqian left Dunhuang in 1943, he frequently held exhibitions, and the exhibition materials during this period were relatively authentic. Therefore, it is speculated from a temporal perspective that the possibility of tampering or copying is relatively small (in other words, there was no time to fabricate counterfeits). The Lujiang Thatched Cottage (庐江草堂) collection contains a list of exhibitions and news briefings by Zhang Daqian from the 1940s (Figure 4 and Figure 5), and with these lists, we can access publications from that time.

Question 4: Regarding the authenticity of the number and circulating versions of Fenben

Quantity

According to Wei Xuefeng from the Sichuan Museum, during his two years and seven months of residence in Dunhuang, Zhang Daqian copied a total of 276 frescoes. At present, the Sichuan Museum has collected 183 of them, while the remaining are kept at the Taipei Palace Museum. Although these data are relatively clear, they are only for reference. According to the statistics of Lujiang Thatched Cottage (庐江草堂), the Sichuan Museum has collected more than 180 Dunhuang frescoes copied by Zhang Daqian, as well as more than 200 Fenben (粉本) and more than 70 ink paintings. The problem is that Zhang Daqian continued to create a large number of works after leaving Dunhuang. Therefore, when studying Fenben’s works during the Dunhuang period, it is necessary to clearly define the time range between 1941 and 1943.

Version

There are different interpretations regarding versions. For example, Zhang Daqian copied a thread draft inside the Mogao Grottoes, but after leaving, he made a Fenben (粉本) copy. Because the latter is a copied version, it is relatively difficult to define. At that time, he was inside the Mogao Cave, and to complete the task as soon as possible, he could only quickly record it and then make copies, which also explains why he drew line manuscripts (线稿). During his time in Dunhuang, Zhang Daqian was in a hurry because of the high cost of living. He lived in Dunhuang for two years and seven months, consuming 5000 taels of gold, and his property and calligraphy were all pawned as collateral.

Research in domestic and international academic circles

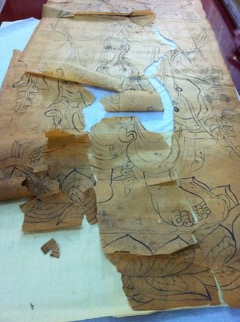

From the perspective of art history, studying paintings from the Dunhuang period involves analyzing images and styles. The evaluation of paintings during this period is based mainly on the interpretation and analysis of historical traces, that is, considering the specific situation of the difficult and hurried conditions in the Mogao Grottoes at that time. This includes considerations such as paper type and copying method. The Dunhuang Fenben (敦煌粉本) in the Lujiang Thatched Cottage (庐江草堂) collection was made from handmade paper from the 1940s using kerosene-wetted paper, which reflects the period. (Figure 3) Moreover, the diaries, survey records, and even lifestyle habits (such as using cigarette paper for recording) of the parties involved also have important reference values. In addition, the information on the original paper used to package the Fenben (粉本) also has a high reference value.

Question 3: What is the destination of the image materials collected by Zhang Daqian in Dunhuang? Did he cause any damage to the Dunhuang frescoes?

When Zhang Daqian left the Chinese mainland, he handed a batch of paintings to his wife. Since his wife still lived in mainland China, she donated these works to the Sichuan Provincial Museum after 1949. Therefore, these paintings by Zhang Daqian are reliable in quality and have been passed down in an orderly manner.

Two pending cases

In 1943, the government decided to establish the National Dunhuang Art Research Institute and hired Chang Shuhong as the person in charge. To collect research materials, Chang Shuhong invited Luo Jimei (1902-1987), Director of the Photography Department of the Central Society, to take photographs and record the Dunhuang Grottoes. [6] From April 1943 to June 1944, Luo Jimei, along with his wife Liu Xian and assistant Gu Tingpeng, went to Dunhuang to shoot the Mogao Caves and Yulin Caves. He not only recorded all the cave frescoes and exterior scenes but also meticulously photographed partial frescoes such as Bodhisattvas (菩萨) and Flying Apsaras (飞天), covering almost all the Dunhuang Grottoes and producing approximately 3000 negatives, which are now collectively known as the Roche Archives (罗氏档案). [7] However, after the photography work was completed, Luo Jimei removed all the negatives and photos, and the National Dunhuang Art Research Institute was unable to retain any information. This incident dealt a great blow to Chang Shuhong, who mentioned in his memoir: “At that time, there were two people, one took all the negatives and the other took all the investigation manuscript materials.”

There are two common doubts about this matter:

- Due to the alkaline water quality in the Dunhuang area, it is difficult to provide suitable conditions for washing the film. It is rumored that Luo Jimei had to bring the film to Chongqing for processing. However, from the completion of photography in 1944 until he departed from the mainland in 1949, why did he not return the film to the National Dunhuang Art Research Institute during this period?

- After Luo Jimei left, Chang Shuhong still had interaction with him, but he did not retrieve this batch of negatives. In 1949, Luo Jimei flew to Taiwan with 3000 negatives. Some people speculate that this may be due to his recognition of the important value of these negatives and the guidance of Zhang Daqian. Notably, before Zhang Daqian left Dunhuang, Luo Jimei lived with him for some time. This is another unsolved mystery.

The Evolution of Guanyin

Since its origin in India, the image of Guanyin has always been that of a very burly male, who is the image of an adult aristocratic man in India. During the Northern and Southern Dynasties, the image of Guanyin gradually developed the characteristic of being both male and female, and images of women gradually emerged. [8] By the Tang Dynasty, the image of Guanyin was mainly female, but at the same time, it still retained some male characteristics, such as a beard. Since then, Guanyin has mostly been portrayed as a woman. However, in the early Kizil Grottoes in Xinjiang, Indian-style Guanyin images can still be seen. The emergence of female images in China signifies a shift in aesthetic psychology and reflects the shaping and influence of different cultures during the dissemination process. According to the Chinese concept, the Bodhisattva represents compassion, and it is difficult for a burly male image to reflect this kind of compassionate image.

The destruction of frescoes

During the preparation of the National Dunhuang Art Research Institute in 1943, Zhang Daqian was reported for damaging frescoes. [9] This accusation needs to be viewed dialectically. The frescoes were formed through the continuous overlapping and covering of paintings from various dynasties. For example, the Tang Dynasty covered frescoes from the Wei and Jin dynasties, while the Song Dynasty covered frescoes from the Tang Dynasty. To record frescoes from different dynasties, Zhang Daqian would peel off the covering layers from the Ming and Qing dynasties when painting to reveal frescoes from the Song dynasty. From the perspective of artistic emotions, this approach is understandable; however, from the perspective of cultural relic protection, this approach is indeed a form of destruction.

Among these frescoes, the most controversial is The Empress Dowager of Taiyuan Wang’s Worship of the Buddha (都督夫人太原王氏礼佛图, Tang Dynasty), which has been severely damaged. Later, Duan Wenjie, the second director of the Dunhuang Art Research Institute, carried out replication and restoration work. Luo Jimei also participated in destructive behavior during the photography process. He first photographed a layer of frescoes on the surface and then peeled off the frescoes inside.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Jinqi Hu, Hong He, Yi Song and Meng Liu. "Fenben or Drawing? An interview on Zhang Daqian’s manuscripts and its title in copying Dunhuang frescoes." JACAC 2, no.1 (2024): 16-27.

AMA Style

Jinqi Hu, Hong He, Yi Song and Meng Liu. Fenben or Drawing? An interview on Zhang Daqian’s manuscripts and its title in copying Dunhuang frescoes. JACAC. 2024; 2(1): 16-27.

© 2024 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References and Notes

1. Jingxuan Zhu, Tang Dynasty Famous Paintings List, (Chengdu: Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House, 1985).

朱景玄,《唐朝名画录》(成都:四川美术出版社, 1985).

2. Wenyan Xia, Illustrated Treasure Book, (Beijing: The Commercial Press, 1930).

夏文彦,《图绘宝鉴》(北京:商务印书馆, 1930).

3. Suxin Hu, “Dunhuang Fenben and Its Artistic Practice,” Art Panorama, no.6 (2022): 19-23.

胡素馨,敦煌粉本及其画工实践,美术大观, no.6 (2022): 19-23. [cnki]

4. Hong Yang, “Artistic Craftsman’s Desperate Management - Introduction to White Sketch Paintings in Dunhuang Paintings,” Art Magazine, no.10 (1981): 46-49.

杨泓, 意匠惨淡经营中 —— 介绍敦煌卷子中的白描画稿, 美术大观, no.10 (1981): 46-49. [cnki]

5. Wutian Sha, Hong Liang, “A Study on Piercing Holes in Dunhuang Buddha Statue Paintings -- Also Discussing the Evolution of Dunhuang Buddha Statue Paintings and Their Production Techniques,” Journal of Dunhuang Studies, no.2 (2005): 57-71.

沙武田,梁红, 敦煌千佛变画稿刺孔研究——兼谈敦煌千佛画及其制作技法演变, 敦煌学辑刊, no.2 (2005): 57-71. [cnki]

6. Hong He, “The Analysis of The Letter Written By Mr.Xiang Da To ‘Mr.Luo and Mr.Gu’,” Journal of the Silk Road Studies, no.00 (2018): 376-386+409.

何泓,向达先生给”罗、顾二先生”信札释实,丝绸之路研究集刊, no.00 (2018): 376-386+409. [cnki]

7. Yunhan Zhang, “Historical Memories Preserved in Black and White — On the American Photography Collection Visualizing Dunhuang,” Dunhuang Research, no.6 (2021): 152-154.

张韵涵, 以黑白图景载历史记忆——大型图录《观象敦煌》在美出版,敦煌研究, no.6 (2021): 152-154. [cnki]

8. Li Xing, “The Interaction and Cultural Dissemination between the Narrative Images of Dunhuang Female Guanyin and Folk Legend Narration: A Discussion on the Localization and Feminization of Guanyin Belief in China,” The Construction of Art Anthropology in China, pp.8, 2017.

邢莉,敦煌女性观音图像叙事与民间传说叙事的互动与文化传播——兼谈我国观音信仰的本土化与女性化,艺术人类学的中国建构, pp.8, 2017. [cnki]

9. Jianjun Xiao, “A Study on the Copying and Cultural Value of Dunhuang and Kucha Murals,” Hundred Schools in Arts, no.1 (2010):198-201+222.

肖建军, 敦煌与龟兹壁画临摹及其文化价值考论,艺术百家, no.1 (2010):198-201+222. [cnki]

10. De Ma, “The Return and Successive Publication of Dunhuang Inscriptions,” Journal of Dunhuang Studies, no.3 (2015):28-32.

马德,敦煌遗书的再度流失与陆续面世,敦煌学辑刊, no.3 (2015):28-32. [cnki]

11. Jiqing Wang, “The Communication between Stein, Wang Yuanlu, and Dunhuang Officials in 1907,” Journal of Dunhuang Studies, no.3 (2017):60-76.

王冀青,1907年斯坦因与王圆禄及敦煌官员之间的交往,敦煌学辑刊, no.3 (2017):60-76. [cnki]

12. He Zhong, “Book exposure and book protection,” China Auction, no.10 (2021):42-47.

钟禾,曝书与书籍保护,中国拍卖, no.10 (2021):42-47. [cnki]

13. Hong He, “The Beautiful Fenben: Research on the Origin and Circulation of Zhang Daqian’s Copies of Dunhuang Frescos,” Journal of Ancient Chinese Arts and Crafts, no.1 (2024):1-15. [CrossRef]

何泓,美丽的粉本:张大千临摹敦煌壁画的粉本及其画稿流传探源,中国古代工艺美术, no.1 (2024):1-15.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Question 1: Do Fenben and copies need to be distinguished?

- Question 2: Is it more appropriate to call it a copy or a Fenben?

- Question 3: What is the destination of the image materials collected by Zhang Daqian in Dunhuang? Did he cause any damage to the Dunhuang frescoes?

- Question 4: Regarding the authenticity of the number and circulating versions of Fenben

- Question 5: How is the auction situation?

- Daqian’s Dunhuang Fenben collected by Lujiang Thatched Cottage

- Question 6: Is there a possibility that the item Stein brought to the British Museum may be a counterfeit?

- Conflicts of Interest

- References and Notes

Fenben or Drawing? An interview on Zhang Daqian’s manuscripts and its title in copying Dunhuang frescoes

by Jinqi Hu1 , Hong He2, Yi Song1 , Meng Liu1 *

1. School of Design, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China

2. China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2024, 2(1), 16-27; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2024.0401a5

Received: February 01, 2024 | Accepted: March 04, 2024 | Published: April 01, 2024

Question 6: Is there a possibility that the item Stein brought to the British Museum may be a counterfeit?

This is indeed possible, but further testing and verification are needed. Japan is highly sensitive and sophisticated in collecting artistic intelligence and was one of the first countries to obtain data on the Stein, Pelliot, and Dunhuang literature. Japanese scholars have already disclosed some issues regarding the counterfeit Dunhuang literature in their articles. Cataloging is one of the best ways to manage cultural relics, and significant progress has been made in the integration of Dunhuang literature. With the disclosure of a large number of Dunhuang studies documents by the International Dunhuang Studies Project, the overall picture of Tibetan scripture cave documents will gradually become clear. In the 1980s, the National Cultural Relics Appraisal Committee sorted all the calligraphy and painting cultural relics in the national collection and published a set of books called the Catalog of Chinese Calligraphy and Painting 《中国书画图目》. The number of related publications in the literature is gradually increasing, and the trend of global digitization is becoming increasingly prominent. The appearance of the Dunhuang Fenben (粉本) will also become more realistic.

Question 1: Do Fenben and copies need to be distinguished?

There were many controversies in ancient times about the practical use of Fenben (粉本). In the academic community, there are also various views on its terminology. Using Rao Zongyi (饶宗颐, 1917-2018) from the Chinese University of Hong Kong as an example, he referred to Fenben as Dunhuang white paintings (白画) or prickly holes (刺孔). In today’s common terminology, the academic community tends to use line drawing (线描或白描). If we discuss the definition of Fenben based on concepts from traditional painting theory or painting history, it may be understood as the initial draft before the production of frescoes, termed piercing (刺孔).

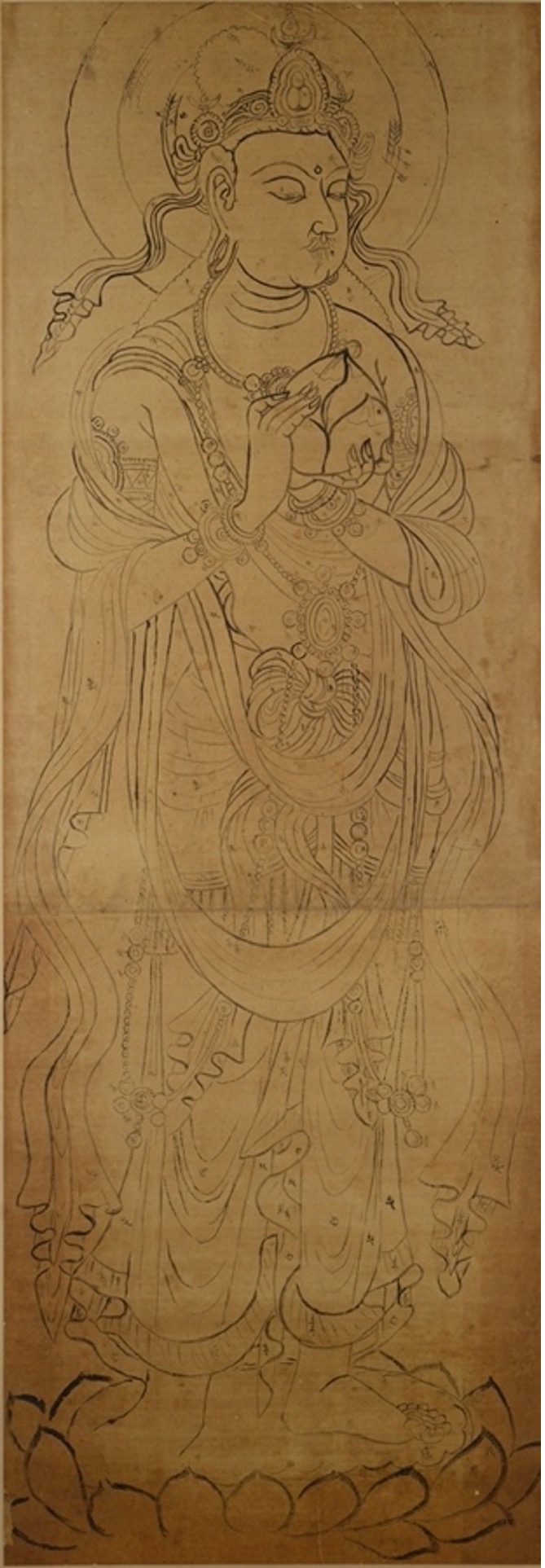

The picture (Figure 2) is a typical line drawing that not only has different colors marked on different parts but has also undergone puncture treatment. It can be classified as a Fenben. For those who do not have painting skills, paper can be pasted on the wall. When the mud layer on the wall is not completely dry, white powder can be applied to the surface of the Fenben (粉本), allowing the white powder to penetrate to the wall through small holes. Then, the Fenben is peeled off, leaving a series of white dots on the wall. These dots are later connected into lines to form a complete painting. This is a transfer printing method for frescoes, and its principle is similar to that of copying, but unlike traditional copying methods, Fenben is applied through holes and powder transfer. This is the most common explanation for this phenomenon. Notably, there are certain differences between Zhang Daqian’s Fenben (粉本) and the original Fenben, and it seems more appropriate to refer to them as copies (摹本). However, they are now collectively referred to as Fenben, especially in the field of frescoes.

The spread of counterfeits

Fake Dunhuang scriptures had already appeared during the Stein period. Stein’s first visit to Dunhuang occurred in 1907, and his second visit occurred in 1914. There is a great deal of discussion about why counterfeits appeared during this period and whether Chinese people participated in the fabrication. In 1910, Stein and Pelliot removed the first batch of documents, but there were still numerous remaining scriptures in Dunhuang. [10] The original plan was to send these scriptures to Beijing in 1910. However, in 1909, Pelliot held an exhibition in Beijing, which shocked Wang Guowei (1877-1927) and Luo Zhenyu (1866-1940). Subsequently, the central government sent a letter to Gansu Province requesting the protection of national treasures, sealing up all remaining scriptures and transporting them to Beijing. Nevertheless, during the process of the Eastern movement, Wang Daoshi (Wang Yuanlu, 1849-1931) secretly hid a large amount of scripture writing. [11] Although the remaining scriptures were indeed safely transported to Beijing, there were incidents of tearing, damage, disappearance, and corruption during transportation. Therefore, it can be inferred that counterfeiting activity increased during this period.

After the scriptures were transported back to Beijing, it was found that numbers had been fabricated. For example, a 10-meter-long scroll had been torn into 10 sections, 9 of which were kept without authorization. At that time, the count was based on the number of scriptures, and it was only necessary to ensure that there was an exact number when submitting them to complete the task. The number of scriptures that have been privately preserved may reach hundreds. It is said that Japanese people have purchased some counterfeit products, but due to a lack of judgment and identification ability, they mistakenly believed that they were genuine. To date, many collections in Japan have been exposed as counterfeits. This transportation made it difficult for Stein himself to accurately distinguish their authenticity, and there may also be counterfeit copies in the second batch of scriptures he took away.

Identification of Counterfeits

After the issue of counterfeits became apparent, the task of counting the number of Dunhuang scriptures became even more challenging. At present, the academic community has numbered more than 70,000 Dunhuang documents. The papermaking technology in ancient China usually included insect prevention treatment, so there were no signs of insect infestation in the scripture writing in the cave. [12] A large number of insect-infested scriptures originate mainly from Japan, which reflects differences in the sources and textures of paper.

Returning to the discussion of Fenben

First, the theme clearly focuses on the Fenben (粉本) made by Zhang Daqian during his time in Dunhuang from 1941 to 1943. Second, we sorted the relevant content in existing publications, compiled a table of contents, and listed the existing locations of Fenben during Zhang Daqian’s Dunhuang period. For example, the specific number of Zhang Daqian’s Dunhuang Fenben (粉本) in the collection of the Taipei Palace Museum can be listed in the specific Fenben directory if more detailed information is needed. Finally, it is crucial to understand whether the Sichuan Museum has released a specific list of its collection of more than 180 Fenben (粉本) pieces. By analyzing images, similarities and differences can be identified through analogy. However, the difficulty of image identification is relatively high, and currently, image identification relies mainly on methods such as literature reviews and image comparisons.

Introduction

The Lujiang Thatched Cottage (庐江草堂) in Hangzhou, collects Fenben (粉本, Ancient Chinese painting terminology, also known as painting manuscripts, which was used by ancient people to draw, first with powder and then with ink over the traces) of Zhang Daqian’s copies of the Dunhuang frescoes, was the subject of this interview. Through this interview, the circulation of Zhang Daqian’s Dunhuang Fenben and their authenticity were discussed. The founder of Lujiang Thatched Cottage, He Hong, believes that it is still uncertain who painted a Fenben (粉本) in the collection of the Dunhuang Research Institute in Gansu because it is the same version as the one from the Lujiang Thatched Cottage; the paper, the style of the linework, and the style of the Chinese labels are all similarly expressed. The Dunhuang Research Institute has not determined the specific year of this piece, only that the time of its drawing was before 1949. The discussion of the Dunhuang Fenben (粉本) is quite complex. One issue is that many of them were not personally drawn by Zhang Daqian. His assistants and students also participated in the work of copying the Dunhuang frescoes. (Figure 1)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of the article.

Question 2: Is it more appropriate to call it a copy or a Fenben?

There are differences among concepts such as a copy (摹本), imitation (仿本), and facsimile (拷贝本), which is a matter for academic debate. For this issue, it is more reasonable to call it a Fenben, as this term has become conventional. If further subdivided, it can also be referred to as a white sketch (白描), line sketch (线描), or painting draft (画稿). Although no prickly hole paintings (刺孔) have been discovered in China at present, prickly hole paintings were mentioned in the Dunhuang scripture cave literature brought to England and France by Marc Aurel Stein (1862-1943) and Paul Pelliot (1878-1945) in the early stages. This indicates that in the same painting, there are some prickly holes (刺孔) and some line drawings (线描).

It is difficult to reach a consensus in the current discussion on Fenben. Fenben, as an art form, has a long history; for example, its application in Chinese painting is extensive. A deeper understanding of the essence of Fenben (粉本) requires, starting from the perspective of art history, systematically sorting out relevant descriptions and definitions in the literature to explore the definition and evolution of its concept.

For example, the Xuanhe Painting Manual (宣和画谱, compiled by the official editor during the Northern Song Dynasty) records the line drawing works of Yan Liben (阎立本,601-673 AD) and Wu Daozi (吴道子,680-759 AD), and it is worth exploring whether it includes a Fenben because, in their era, Fenben (粉本) already existed for theoretical exploration and practical application. In addition, it is worth investigating whether Fenben was described and defined in the Records of Famous Paintings of All Dynasties (历代名画记). To determine the origin of the Fenben (粉本) concept, it is necessary to systematically determine the history of the art. It is worth noting that even though Fenben objects may have existed before the Tang Dynasty, they are likely to have been destroyed and no longer exist.

Lu Fusheng’s Complete Book of Chinese Painting and Calligraphy (中国书画全书) includes all painting theories, among which the Southern Dynasty painting theorist Xie He’s Record of Ancient Paintings (古画品录) and Zhang Yanyuan’s Record of Famous Paintings of All Dynasties (历代名画记) mention Fenben (粉本), making this an important direction for finding the source of the concept. For Fenben’s research, it is necessary to focus on its concepts. Rao Zongyi explored the issue of tracing the origin of Dunhuang Fenben in his book Dunhuang White Paintings (敦煌白画) and conducted in-depth research in conjunction with Dunhuang scripture cave literature. His research results have a certain representativeness. In addition, copying has multiple dimensions. For example, subjective replication (意临) and objective replication (对临) are two distinct types. The latter respects the copying of the original work. The former may involve personal thinking, also known as subjective imitation. Scholars such as Li Dinglong, Zhang Daqian, Chang Shuhong, and Duan Wenjie have different understandings of Dunhuang fresco copying and ascribe to their unique views and methods.

Zhu Jingxuan’s Record of Famous Paintings of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝名画录) records a dialog between Emperor Ming of Tang and Wu Daozi, stating that Wu Daozi once painted over 300 miles of landscape along the Jialing River, which was completed in one day. [1] Emperor Xuanzong of Tang asked about his situation, and he replied, “I have no Fenben (粉本), and I will keep it in mind.” This dialog mentions a clear concept of Fenben, which can serve as research evidence. Xia Wenyan’s Illustrated Treasure Book (图绘宝鉴) mentions that “ancient painting manuscripts are called Fenben (粉本).” [2]

Professor Sarah E. Fraser from the University of Heidelberg in Germany believes that Fenben refers to early manuscripts, and the earliest record of this concept in the literature can be traced back to the mid-19th century, approximately the same as the Dunhuang Fenben (粉本) discussed in this article. According to literal translation, if “ben (本)” is understood as a stage or a piece of work in the artist’s creative process, then Fenben (粉本) can be interpreted as a “powdered version,” or even a “powdered draft”. [3] Among the Six Methods of Painting (绘画六法) proposed by Xie He, there is one piece called “Transfer Copying” (转移摹写). Transfer copying refers to copying a model work, with the copied work called a Fenben. Duan Wenjie also mentioned that “the purpose of copying determines the method of copying.” He summarized the three basic methods of copying frescoes in Dunhuang: objective copying (客观临摹), complete copying of old colors (旧色完整临摹), and restoration copying (复原临摹).

After studying the Dunhuang frescoes copied by Zhang Daqian, Yang Hong believes that there may be two possible sources of Fenben (粉本): one is based on the Fenben left by predecessors, which was passed down by craftsmen through copying. The second is to choose classic fresco works that have already been produced by predecessors and copy them. [4] The specific techniques can also be divided into two types. One is to use a needle to prick small holes based on the outline of the painting, then inject chalk powder into the paper or use the ink penetration method to print so that the clay powder or ink dots penetrate the paper, silk, and wall, and then to draw according to the powder or ink dots. The second is to apply chalk powder to the back of the painting and to use hairpins, bamboo needles, etc., to lightly draw and print along the front contour line. Then, marking or coloring, which is similar to the function of commonly used modern carbon paper, is begun. [5]

Abstract

The scholarly community has yet to reach a consensus on the authenticity of Zhang Daqian’s copies of frescoes from the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang and the path of their circulation. This interview revolves around the Fenben (粉本) created by Zhang Daqian at Dunhuang and compares the concepts of Fenben and the manuscripts. Through dialog, this article discusses the role and function of the Fenben (粉本) concept in traditional Chinese painting. It is hoped that through this interview, the two concepts of Fenben and manuscript can be identified and traced back to their origins and, at the same time, trigger an in-depth academic discussion on the circulation of Zhang Daqian’s works copied at the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang.