Belief in Ascension

Mountains are the habitat for the birth and production of all things, and they are a space full of life energy. In The Classic of Mountains and Seas of the “five hidden mountain scriptures,” the customs and products of the mountains included rituals and witch doctors. The mountains were the pillars or ladders of heaven that ancient sorcerers used to connect with the heavens. The Book of Songs contains the statement, “The mountain peaks towered into the clouds. The divine spirit descended, and Fu Hou and Shen Bo were born [29].” Zhuangzi Peripateticism, there is the following passage: “The legend tells of a mysterious figure residing on the Gushe mountain with skin as pure and white as snow, and an appearance so beautiful that it resembled that of a young maiden [30].” For the immortal mountains where immortals lived, the Han Dynasty people expected to use sacrificial ceremonies. On the one hand, they hoped to receive the blessings of immortals to ensure safety in real life; On the other hand, they also hope to be able to move immortals and become immortals after their own death. In the Han Dynasty, the belief in “immortals” was part of two major mythological systems in the east and west, represented by “Kunlun Mountains” and “Three Mountains on the Sea.” In his article The Integration of Kunlun and Penglai Mythological Systems in Zhuang Zi and Chu Shi, Gu Jiegang pointed out, “The myth of Kunlun originated in the western plateau region. Its magical and magnificent story, spread to the East and combined with the natural condition of the vast sea, formed the Penglai mythological system in the coastal areas of Yan, Wu, and Yue [31].” The Classic of Mountains and Seas records scenes from the fairy world featuring the Kunlun Mountains and the Queen Mother of the West. In The Classic of Mountains and Seas - Xishanjing, the following passage occurs: “Yushan is the place where the Queen Mother of the West lives. The appearance of the Queen Mother of the West is like that of a person, with the tail of a leopard, the teeth of a tiger, and the ability to howl, with fluffy hair. She is a god sent by heaven to be in charge of epidemics and executions.” Another passage reads: “Kuncang Mountain stands tall in the northwest and is the capital of the Heavenly Emperor on earth. The Kunlun Mountains have a radius of 800 kilometers and a height of 18000 meters. There is a piece of rice on the mountaintop that is big enough to be hugged by five people like a tree. There are nine wells on each side of the Kunlun Mountains, each with a fence made of jade. There are nine gates on each side of the Kunlun Mountains, and each gate is guarded by divine beasts, making it a gathering place for many heavenly gods. The gathering place of numerous heavenly gods is between the Eight Mountains and Rocks on the shore of Chishui. Without exceptional skills, one cannot climb those mountains and rocks.” Another passage state, “South of the Western Sea, on the shore of the quicksand, after the Red Water and before the Black Water, there is a great mountain called the Mound of Kunlun. There is a god with a human face and a tiger body, with patterns and a tail, who lives in the Kunlun Mountains. Below it was the abyss of weak water, and beyond it was the mountain of never-ending fire; the cast of the mountains was rolling. The one who lives in a cave with tiger teeth and a leopard tail is named the Western Queen Mother. This mountain has all things [32].”

Han poetry in the forms of Lefu (乐府) and Fu (赋) always describe fairylands as occurring in the mountains. Han and Wei Lefu Fengxian (Volume XII) contains the following passage, “The mountains to the west are so high and boundless. There are two fairy children above, who do not drink water or eat anything. They gave me a pill, and after taking it, I can soar in the clouds [33].” In Shu Du Fu, Yang Xiong said: “This long road is over 5000 miles long, passing through undulating mountains, deep canyons, and continuous towering mountains. It appears to that the peaks are competing, and when they touch rocks, they can even spew out clouds and mist.” Zhang Heng, in Nandu Fu, said, “Kunlun Mountain cannot be crossed, and Langfeng Mountain cannot be climbed [34].”

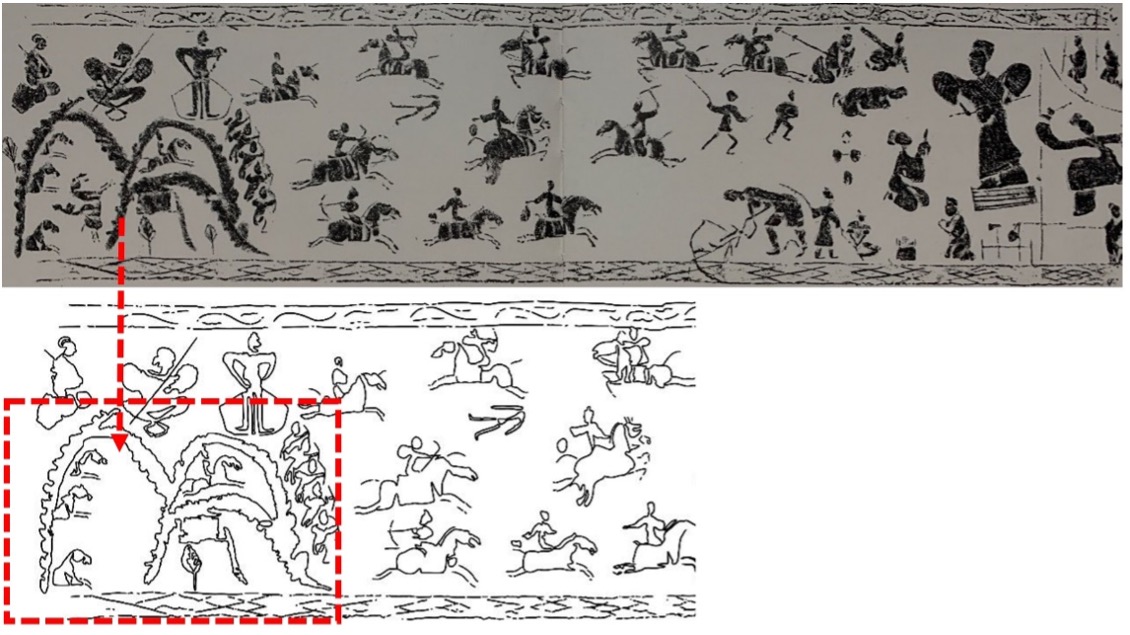

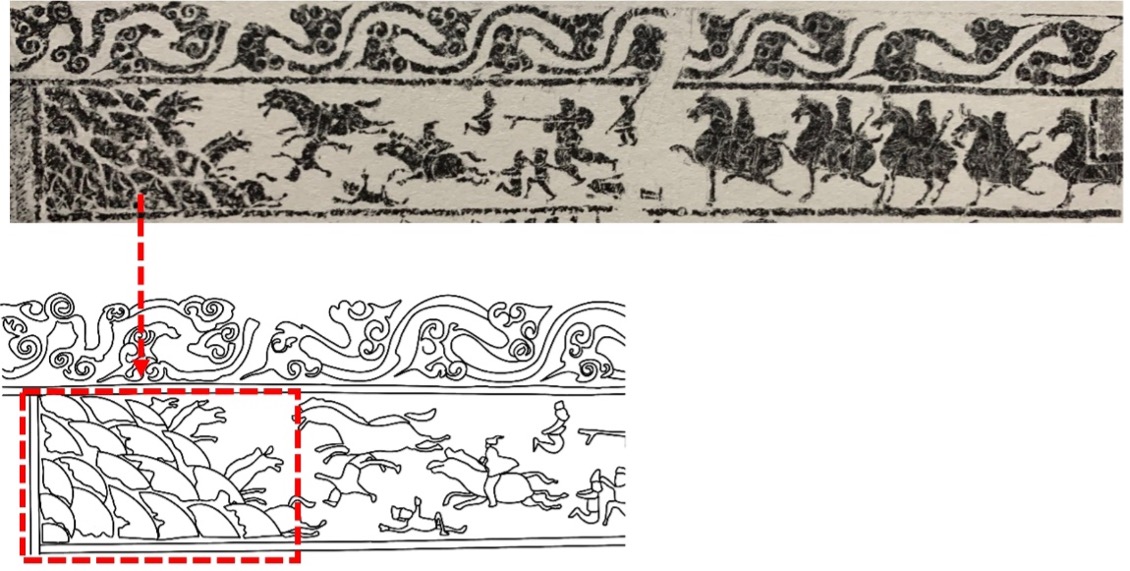

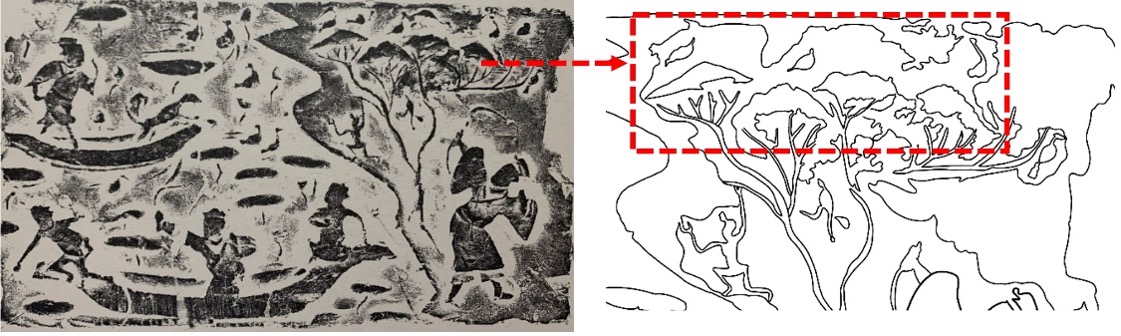

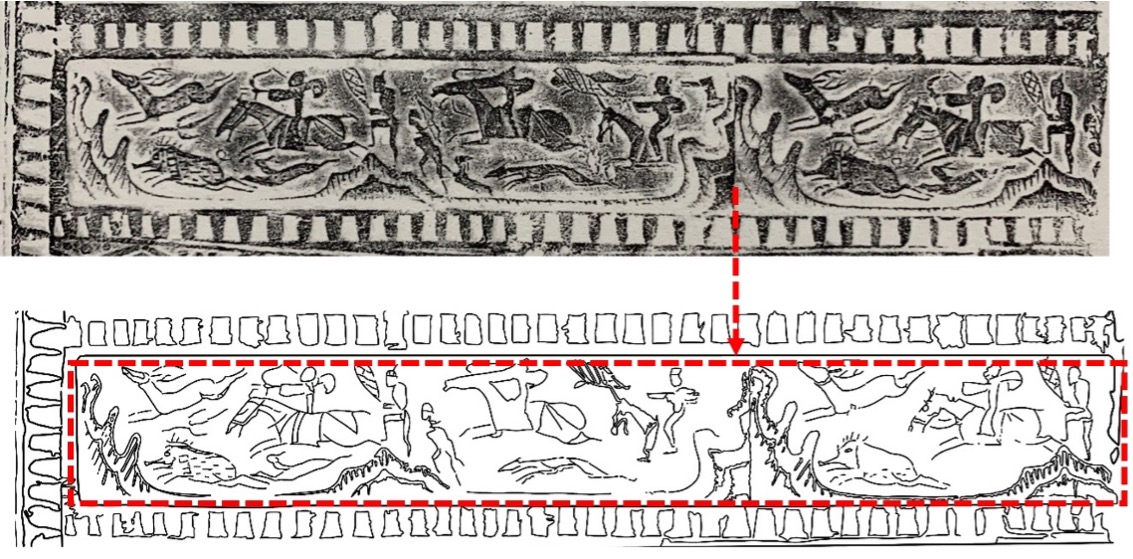

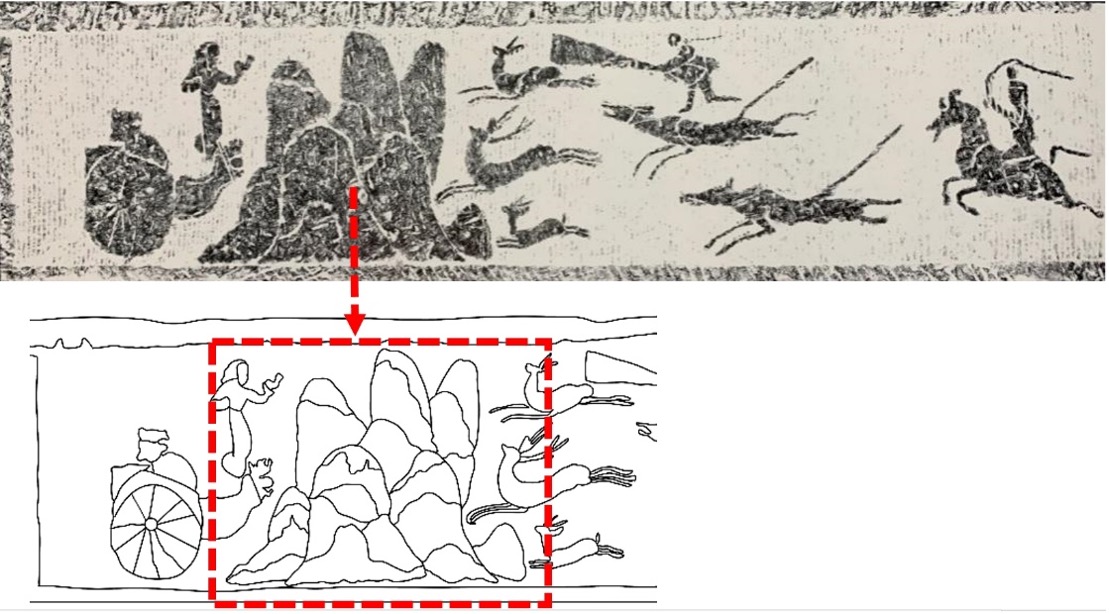

Hunting portraits generally include scenes of hunting in mountains and forests, bullfighting, tiger fighting, and mounted archery. Yingzhuang, Nanyang City, Henan Province, has a hunting portrait with mountain peaks on the left side of the picture, undulating in height, surrounded by running prey and people in the process of hunting (Figure 8). In Nanyang City, the Henan Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology has a collection of hunting portraits (Figure 9), including one surrounded by mountains, fierce dogs and rabbits, horseback riding and hunting scenes throughout. The cart-based hunting portraits from the Yulin area in northern Shanxi Province are also quite numerous. Examples include Suide Yanjiakou, a hunting portrait that contains pictures of the peaks and mountains, birds and animals, and hunters shooting and chasing. Huns and hunting occupy a very important position in the Han dynasty’s economic life. The Historical Records Xiongnu Legend records the following passage, “the Huns learn how to ride when they are children. They begin to draw the bow to shoot birds and rats, then when they are a little older, they shoot foxes and rabbits. Since the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States, with the development of animal husbandry, hunting takes secondary importance, along with the practice of martial arts [22].” Book of Han: Treatise on Geography includes the following passage: “Anding, Beidi, Shangxian, Xihe, all close to the Rongdi (戎狄), practiced preparations for war when they were full of energy, and learned first to shoot and hunt [23].”

Hunting is a means for rulers and soldiers to practice martial arts; Emperor Wu of Han built the Shanglin Yuan specifically for hunting. One historical account mentions that “in the third year of Jianyuan, Emperor Wu began to go on a patrol in disguise, reaching Chiyang in the north, Mount Huangshan in the west, Changyang Palace in the south, and Yichun Garden in the east [24].” In A Short History of Chinese Art, Teng Gu said, “During the Zhou Dynasty, the stone drum text (石鼓文) was intended to praise the king’s hunting in Qishan. Talking about military affairs due to skills in hunting and renting is also a type of monument [25].” Another text includes the following passage: “It is appropriate to engage in hunting activities in autumn. Through this type of hunting, soldiers can practice and become familiar with war equipment, which is an important form of etiquette [26].” By the Zhou Dynasty, the hunting ritual was standardized and institutionalized and was an important part of the “rule of the country by ritual” (以礼治国). “Hunting” patrols also use hunting practice to show off the meaning of force deterrence [27]. In the Discourses of the States-Qi, the following activities are listed: “Farming, hunting, fishing nets, archery [28].” Field hunting involves hunting in the winter for military training. Hunting was originally an activity that people had to do to obtain food and resources for survival, but with the development of agriculture, the sources of food and clothing became richer, and its status in daily life was gradually replaced by ritual and military uses of these skills.

The earliest record of Mount Penglai in the literature is found in The Classic of Mountains and Seas: “Mount Penglai is in the middle of the sea, and the city of adults is in the middle of the sea [40].” The combination of the Penglai Mountain in the sea with the “Abbot” and “Yingzhou” sacred mountains forms the structure of the “Three God Mountains” in the Han Dynasty. The Records of the Grand Historian (《史记·封禅书》) contains the following passage: “Since the kingdom of Wei, Xuan, and Yan Zhao made people enter the sea to seek Penglai, Fangzhang, and Yingzhou. These three mountains of the gods are rumored to be in the Bohai Sea, not far from the people, and then the wind will lead boats to it. The cover [route] is known only to each person; the immortals and the elixir of immortality are in the same place [41].”

A more detailed account of the fairyland space of the three sacred mountains of Penglai is found in Liezi Tang Wen: “I do not know how many hundreds of millions of miles east of Bohai Sea it lies where there is a big gully, but it is only a bottomless valley, and its bottomless abyss is called the return of the ruins. The water of rivers from all directions is also injected into it, but there is no increase or decrease. There are five mountains among them: the first one is called Daiyu Mountain, the second one is called Yuanqiao Mountain, the third one is called Fanghu Mountain, the fourth one is called Yingzhou, and the fifth one is called Penglai Mountain. Its height is 30,000 miles, the top of the plateau is at nine thousand miles, and the middle of the mountains is 70,000 miles away from the nearest neighbors. On the platform, one can see all the gold and jade; the beasts and animals have pure onyx. All the trees of Rengan grow in clusters, all the fruits have a taste, and all those who eat them do not grow old or die. The people who live there are all of the immortal and saintly kind, and those who fly to and from them day and night cannot be counted [42].” Penglai Divine Mountain had prominent fairyland qualities since the Han and Wei Dynasties, when poets and fugitives were believed to travel to the space of the immortal gods. In the late Eastern Han Dynasty, the belief in Penglai Immortals and the belief in Western Queen Mother Immortals in the Kunlun Mountains tended to merge.

The Representation of Mountains in Han Portraits

by Fang Lan *

School of Fine Arts, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2023, 1(1), 33-48; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2023.1122a3

Received: September 1, 2023 | Accepted: October 23, 2023 | Published: November 22, 2023

Introduction

Mountains are an important motif in the literature and art of the Han Dynasty. Literary works such as Han Fu (汉赋), Huainan Zi (淮南子), and San Fu Huang Tu (三辅黄图) all have descriptions of mountains. Many mountain patterns are depicted in the plastic arts, such as Han Dynasty stone carvings, bricks, lacquerware, and bronzeware. The patterns and characteristics of rendered mountains had already appeared during the Shang and Zhou dynasties. By the Han Dynasty, the rendered forms of mountains had diversified, including both descriptions of the real world and depictions of reverence and faith in the immortal realm. These images were in a transitional stage of aesthetic consciousness about the metaphysics of mountains and forests. This article provides an interpretation of the “mountains” of the Han Dynasty, from schemata to literature, systematically sorting out the development of landscape imagery from natural landscape forms to “external phenomena” and exploring the important significance of Han Dynasty decorative patterns in the development of traditional Chinese decorative patterns.

Realistic Scenery

Many scholars have noted the important role of the Han Dynasty mountain schema in Chinese culture and art. In Chinese Mythology, Legends, and Ancient Novels, Koichiro Konan demonstrated the development of the combination of the Kunlun Mountains and the Western Queen Mother schema, as well as how the concept of the Kunlun Mountains as the center of the world was presented. Starting from the content of the Classic of Mountains and Seas, Liu Xicheng divided the schema of the Kunlun Mountain and the Western Queen Mother into “The capital of the Heavenly Emperor on earth” (帝之下都), “Towering pillar that rises into the sky” (天之中柱), and “Mountain of Youdu” (幽都之山). Gao Lifen’s paper Vertical and Horizontal: Images of Shenshan in Han Dynasty Portrait Stones analyzed the visual connotations of the Kunlun Mountains and Penglai Mountain in Han Dynasty portrait stones based on the vertical and horizontal spatial layouts in Shenshan landscaping. Huang Peixian, in his article Landscape Images Excavated from Han Tombs: Rethinking the Origin of Chinese Landscape Painting, deduced that the embryonic form of Chinese landscape painting was formed during the Han Dynasty by tracing the development of the image of Zhongshan in the Han portrait. Related research has demonstrated that the Han Dynasty mountain pattern not only included layouts of mythological landscapes but also had countless connections with landscape painting during the Wei and Jin dynasties.

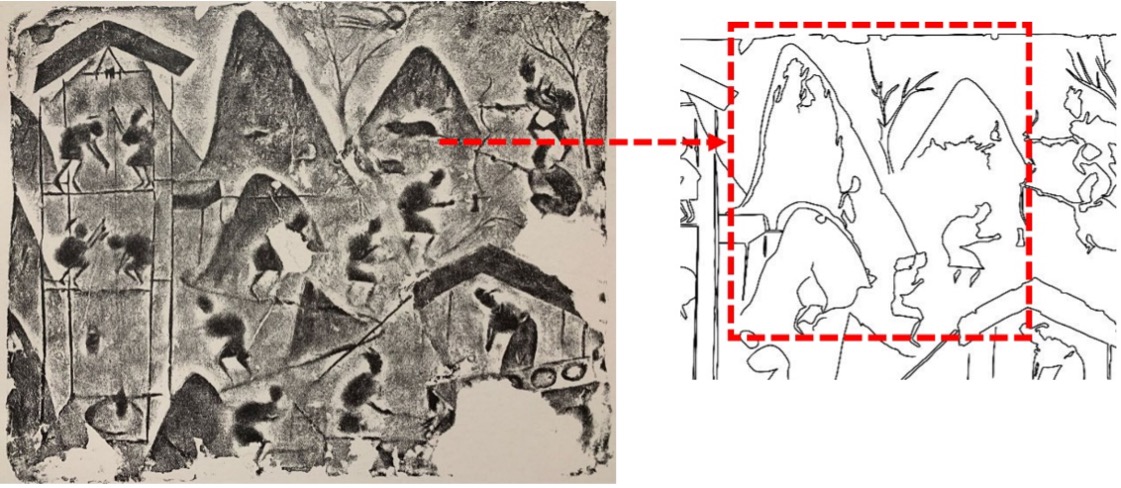

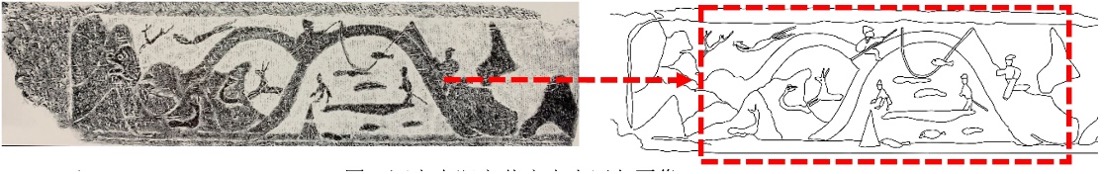

From the unearthed Han portrait stone, artists of the Han Dynasty appeared to represent landscape patterns realistically. Han portraits depict scenes of daily life and livelihoods, which not only portrays people’s lives but also reflects an aesthetic idea of the schema relating heaven and earth. The “Rent Collection Map,” “Salt Well Map,” “Farming Map,” and “Fishing and Hunting Harvest Map” in the Han Dynasty portraits, which are based on mountain patterns, depict the ideal living conditions of Han Dynasty scholars. The Sichuan Museum has a collection of “salt-making” portraits (Figure 1). The entire scene of salt making is depicted amidst undulating mountains, where there are people carrying firewood and hunting. The picture titled Fishing, Hunting, and Picking Lotus (Figure 2) shows a pond, lotus seeds, and lotus leaves on the left, a pond bank on the right, and trees on the bank. In the distance, there are continuous hills [1]. The portrait of a fish, preserved in Yingzhuang, Nanyang City, Henan Province (Figure 3), depicts running deer, fishermen, small boats, and fish amidst the undulating peaks. In these portraits, the composition of the mountains has not yet established a fixed pattern; the landscape paintings of the Wei and Jin dynasties would later have their own pattern described by Zhang Yanyuan in his Records of Famous Paintings of All Dynasties: “If Sometimes people paint bigger than mountains. Usually, some trees and stones are added to complement the flat ground. The arrangement of trees is like a person’s outstretched arms and outstretched fingers [2].” Based on existing materials, it can be inferred that the proportion of mountains to people in the Luoshen Appraisal Painting and the proportion of mountains to people in the Han Dynasty portraits belong to a basic stage of development.

The representation of natural images is an important motif in human decoration, and the relationship between humans and nature constitutes the most fundamental relationship. The concept of “observing objects and taking images” in the Book of Changes is the starting point of human observations of nature for constructing the world. Early human life was closely linked to mountains, and in ancient societies with low levels of economic productivity, mountains and rivers provided various living guarantees. Shenzi said, “Mountains and rivers are the food and clothing of the world [3].” The Discourses of the States also records the important significance of mountains, forests, and rivers in the national economy and people’s livelihood. When King Ling of Zhou wanted to govern the two rivers of Gu and Luo, the Crown Prince Jin advised, “I heard that ancient rulers did not destroy hills, fill swamps, block rivers, or excavate lakes. Hills are the aggregation of soil, swamps are the home of life, rivers are the offspring of the Earth’s atmosphere, and lakes are the collection of water flow [4].” The praise of mountains and rivers in The Book of Songs is resource oriented, mostly about whether there are edible wild fruits, vegetables, animals, and fish in the mountains and rivers. The poem Shao Nan Grass Insect says, “When you climb the Nanshan Mountain, you can pick fresh ferns and pea seedlings [5].” The Han Shi Wai Zhuan said, “That which is called a mountain is what everyone looks up to. Plants are born in the mountains, birds and beasts rest in the mountains, and all things benefit from the mountains. The mountain nurtures clouds, guides the wind, stands between heaven and earth, and tranquilizes the country. That is why benevolent people like mountains [6].” Ban Gu in his Ode to the West Capital states: “There are towering mountains in the south, surrounded by forests and deep valleys, where treasures of land and sea are hidden. Lantian jade is even more famous worldwide. Shangzhou and Luozhou are located on its edge. Hu County and Du County are adjacent to it. Ponds and lakes formed by rushing spring water are scattered everywhere. Here are dense forests and orchards, fragrant flowers and plants. The richness of materials is claimed to be comparable to that of Sichuan [7].” The literature extensively describes various treasures hidden in mountains and steep mountains, such as beautiful jade in blue fields, dense bamboo forests and orchards, and beautiful and fragrant vegetation. People leave the imprint of mountains not only in literary works but also in plastic arts, and early pottery and bronze have recorded this important pattern. For example, the Juxian Museum in Shandong Province has a gray carved statue with basket patterns throughout the body and a pattern of the sun, moon, and mountain peaks overlapping in the abdomen. The occurrence and development of decorative patterns are conscious choices made by humans. These special geological landforms, such as famous mountains and rivers, are not only the environment for the survival and activities of the ancestors but also provide them with rich materials for living. The transition from mountains in nature to mountains in art and culture is the initial way in which mountain patterns occur.

Abstract

The patterns and characteristics of mountains have appeared in portraits since the Shang and Zhou dynasties. The patterns of mountains in the Han dynasty depicted the real world, expressed reverence and belief in the immortal realm and were in a transitional stage of aesthetic consciousness in the metaphysics of mountains and forests. The mountains in the realistic landscape reflect life and aesthetically reflect the ideal schema of heaven and earth. Ritual symbols use fixed patterns of mountains, hunting, and war to depict the rituals of offering sacrifices to the heavens and mountains, as well as the bestowal of divine orders and mountain sacrifices. Famous mountains and rivers were the places where immortals lived in the popular imagination of the Han Dynasty. The belief in “immortality” formed two major mythological systems in the east and west, represented by the “Kunlun Mountains” and the “Three Mountains on the Sea,” which gave rise to a series of mountain patterns associated with each mythological system. In the context of etiquette and symbolism, the Han Dynasty depiction of mountain patterns developed into diversified forms, reflecting the traditional Chinese natural aesthetic approach in which “landscape painting expresses the artistic conception of the Tao through formal beauty.”

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

References and Notes

1. Lusheng Chen, ed., Chinese Han Paintings (Nanning: Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, 2018), 283, 271.

2. Yanyuan Zhang, Records of Famous Paintings of All Ages (Beijing: People's Fine Arts Publishing House, 2004), 26.

3. Integration of Various Scholars (5), (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1954), 11.

4. Discourses of the States, translated and annotated by Tongsheng Chen (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2013), 110.

5. [Qing] Ruan Yuan, ed., Thirteen Classic Commentaries and Sparse Notes (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2015), 1219.

6. [Han] Han Ying, Collection and Interpretation of Han Poetry's External Biographies (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2020), 105.

7. [Liang] Xiao Tong, Selected Writings, annotated by [Tang] Li Shan (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2016), 24.

8. The Songs of Chu, translated and annotated by Lin Jiali (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2010), 345.

9. [Qing] Ruan Yuan, ed., Thirteen Classic Commentaries and Sparse Notes (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2015), 897.

10. [Song] Fan Ye, Book of Later Han Dynasty, annotated by [Tang] Li Xian, et al (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2005), 987.

11. [Han] Zhang Heng, Translation of Selected Writings of Zhang Heng, translated and annotated by Zaiyi Zhang, et al (Chengdu: Bashu Press, 1990), 142.

12. [Tang] Fang Xuanling: The Book of Jin (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1974), 1544, 1359.

13. [Song] Fan Ye, Book of Later Han Dynasty, annotated by [Tang] Li Xian, et al (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2005), 1182.

14. Qinggu He, Sanfu huangtu jiyexue (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2005), 234.

15. Xicheng Liu and Qi You, eds., Mountains and Symbols (Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2004), 1.

16. Lusheng Chen, ed., Chinese Han Paintings (Nanning: Guangxi Fine Arts Publishing House, 2018), 88, 142, 160.

17. Discourses of the States, translated and annotated by Tongsheng Chen (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2013), 28.

18. [Han] Sima Qian, Historical Records (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2005), 1359.

19. Xicheng Liu and Qi You, eds., Mountains and Symbols (Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2004), 68.

20. [Qing] Ruan Yuan, ed., Thirteen Classic Commentaries and Sparse Notes (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2015), 2885.

21. [Qing] Ruan Yuan, ed., Thirteen Classic Commentaries and Sparse Notes (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2015), 1656.

22. Lanying Kang, “Hunting Activities in Shangxian County as Reflected in Picture Stones,” Relics and Museolgy, no.3 (1986): 48-52+54-55. [cnki]

23. [Han] Ban Gu, Han Shu (The Book of Han), annotated by [Tang] Yan Shigu (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2002), 1644.

24. [Han] Ban Gu, Han Shu (The Book of Han), annotated by [Tang] Yan Shigu (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2002), 2847.

25. Gu Teng, A Short History of Chinese Art (Jinan: Jinan Publishing House, 2019), 6.

26. [Qing] Ruan Yuan, ed., Thirteen Classic Commentaries and Sparse Notes (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2015), 5288.

27. Pingli He, The Idea of Chongshan and Chinese Culture (Jinan: Qilu Books, 2001), 68.

28. Discourses of the States, translated and annotated by Tongsheng Chen (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2013), 239.

29. [Qing] Ruan Yuan, ed., Thirteen Classic Commentaries and Sparse Notes (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2015), 1219.

30. The Collected Explanations of Zhuangzi, translated and annotated by Guying Chen (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2016), 24.

31. Jiegang Gu, “The Integration of the Two Mythological Systems of Kunlun and Penglai in <Chuangzi> and <Chu Ru>,” in Chinese Literature and History Series, No. 2, eds. Dongrun Zhu (Shanghai: Shanghai Classics Publishing House, 1979).

32. Shanhaijing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), translated and annotated by Tao Fang (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2011), 50, 48, 264, 322.

33. Huang Jie, Hanwei Lefu Fengjian (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2008).

34. [Liang] Xiao Tong, Selected Writings, annotated by [Tang] Li Shan (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2016), 119, 75, 69.

35. Xicheng Liu and Qi You, eds., Mountains and Symbols (Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2004), 159.

36. Huai Nan Zi, translated and annotated by Guangzhong Chen (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2012), 200, 204.

37. [Song] Hong Xingzu, Auxiliary Notes to the Chu Rhetoric, ed. Huawen Bai, et al. (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2015), 95.

38. Shi Yi Ji, translated and annotated by Xingfen Wang (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2019), 352.

39. [Japan] Anju Xiangshan and Nakamura Zhangba, “Hetu Kuo Di Xiang,” in Re-edited Wei Shu Integration (6).

40. Shanhaijing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), translated and annotated by Tao Fang (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2011), 282.

41. [Han] Sima Qian, Historical Records (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2005), 1370.

42. Liezi, translated and annotated by Beiqing Ye (Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2011), 116.

43. Boshan furnace is the most common style of fumigation furnace in the Han Dynasty. The top of the Boshan furnace cover is designed in the shape of a mountain, symbolizing the “Boshan” in the fairyland of the East China Sea.

© 2023 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Fang Lan, "The Representation of Mountains in Han Portraits." JACAC 1, no.1 (2023): 33-48.

AMA Style

Fang Lan. The Representation of Mountains in Han Portraits. JACAC. 2023; 1(1): 33-48.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Realistic Scenery

- Ceremonial Symbol

- Belief in Ascension

- Conclusion

- Funding

- Conflicts of Interest

- References

During the Han Dynasty, great progress was made in agricultural production, as seen in records of hunting villas and banquets in palace gardens. These activities had a spacing and relaxing effect on those who were officials at court. The hermits of the Han Dynasty, such as alchemists and hermits, who lived in the mountains as literati, yearned for a natural environment like a fairyland in the mountains and forests, to the extent that they brought their subjectivity back from an aesthetic perspective to the natural landscape beyond humanity. Scholars and celebrities live in seclusion in nature, far from worldly life, and entertain themselves in the environment of mountains and forests. This artistic creation activity with the theme of natural mountains and forests has appeared as early as the pre Qin period. In the Chu Ci Jiu Tan, it was stated, “Like Xu You Boyi (许由伯夷), who is noble and pure, like Jie Zitui (介子推), who hides deep in the mountains without any desires or demands [8].” The entire poem Xiaoya Nanshan Youtai is inspired by the southern mountains: “There is Chinese alpine rush on the southern mountain, and quinoa grass on the northern mountain. A virtuous person is very happy, and for the country, they have an endless lifespan [9].”

With the consolidation of centralization, the identity and status of scholars underwent historical changes, and the aesthetic taste for seclusion became more prominent in the late Eastern Han Dynasty. Feng Yanchang thought about “climbing the steep slope to gaze into the distance, overlooking the universe. By observing the terrain and landscapes, reflecting on the ancient achievements and setbacks, experiencing the twists and turns of the path and the decline of morality [10].” Zhang Heng elaborated on his views on life amidst political disappointment in his Returning to the Land Ode [11]. The return to the field mentioned in the poem is precisely the exhaustion and helplessness he has long experienced in the complex world of officialdom, which inspired him to yearn for the free and fresh atmosphere and independent spirit of rural life. According to the biography of the Book of Jin, Sun Chuo said, “I lived in Kuaiji, traveling for about ten years.” Ruan Ji described his days as, “Climbing mountains and rivers, forgetting to return after the day [12].” Xie Lingyun’s poetry expresses metaphysical philosophy through the depiction of natural mountains and rivers through his understanding of mountains and forests. The poem Returning the Stone Wall to the Lake states: “The weather changes at dusk, and the mountains and rivers contain clear light. The lightness of the landscape delights people, and the wanderers forget to return.” In their secluded life, literati and celebrities view traveling to the mountains and rivers as a form of spiritual enjoyment that nourishes their character and brings them to the ideal location for developing their own personality, which provides a good foundation for the social creation of landscape literature and painting.

The generation of culturally influenced mountain landscapes is reflected by imitating the scale and form of natural mountains, combined with water, plants, and animals, and moving closer to natural forms. The gardens built by Liang Ji in the Eastern Han Dynasty were described in the following verse: “The deep forest, without its source, is like a natural creature. Strange birds and beasts roam freely through it [13].” Yuan Guanghan’s garden, which features “torrents of water pouring into them, stone formations forming mountains, rising more than ten zhang in height and extending for several miles [14],” reflects the aesthetic consciousness of imitating nature in the creation of mountain landscapes in the Han Dynasty.

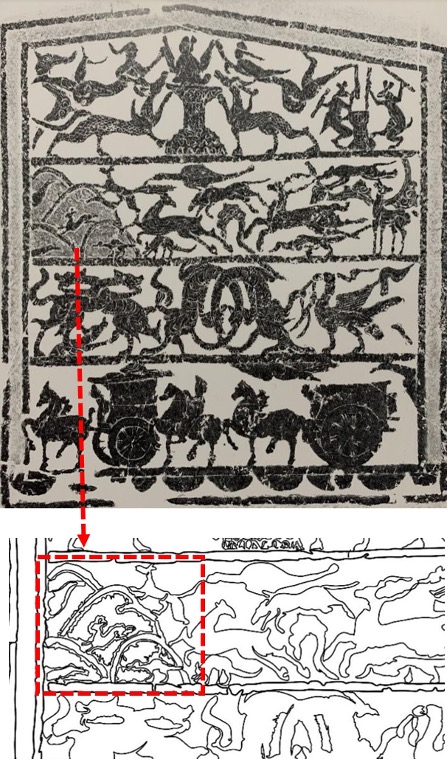

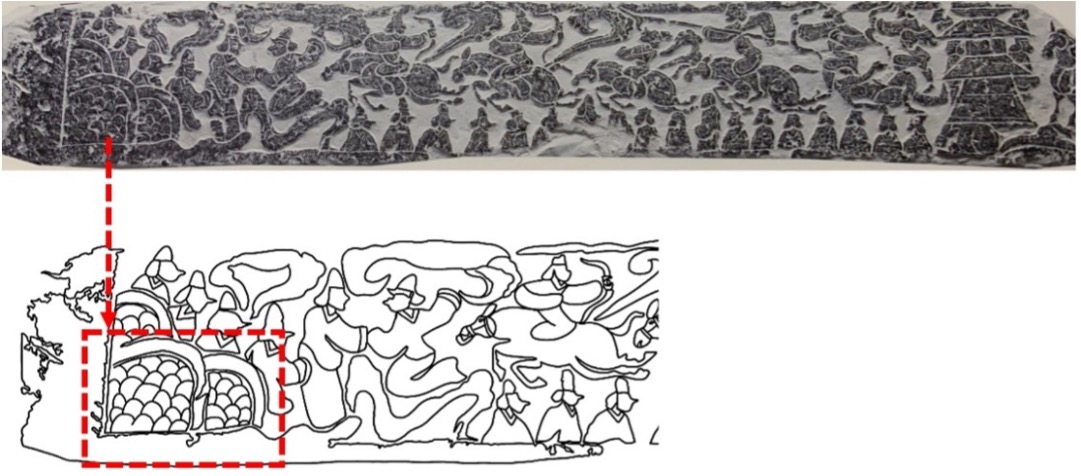

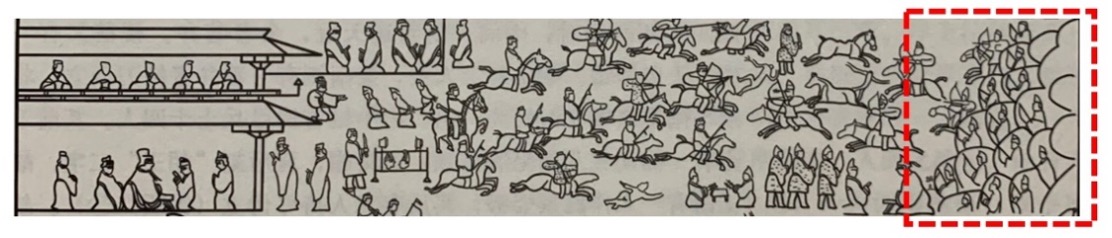

The development of literature and art in the Han Dynasty was a finalization and extension of the cosmic iconography of the Han Dynasty. The fixed patterns of war, hunting and mountains in Han portraits have special ritual characteristics. In the "War and Hunting Portrait" on the west wall of the Xiaotang Mountain (孝堂山) Ancestral Hall in Changqing County, Shandong Province, there are fourteen bow-wielding soldiers on one side of the picture, which is carved with cascading mountains (Figure 4). In west Tengzhou, Shandong, the portrait that gives an account of the Hu-Han War (胡汉战争) (Figure 5) has a picture on the left which is the fish scale mountain, while the right side is full of scenes of the Hu-Han War. In Zoucheng city in Shandong, the Cultural Relics Bureau has collections of Hu-Han War portraits (Figure 6), including one in which the left side of the picture is engraved with layers of mountain peaks, with each mountain in front of the engraved head of a human. Three horses run out of the mountains, and two Hu riders are fleeing in defeat [16]. A portrait of the Hu-Han War in the collection of the Xinye County Museum, Henan Province (Figure 7) has one corner in which a towering mountain is depicted, surrounded by war scenes. In ancient times, when the feudal states were established, well-known mountains and rivers were an important source of support. The mountains and rivers dominate conditions of flood and drought and had a bearing on the country’s ability to sustain itself and the fate of the king. In the second year of King You of the Western Zhou Dynasty, an earthquake occurred. Bo Yangfu (伯阳父) said: “Now that the Zhou Dynasty is almost at the end of the Second Dynasty, its source of rivers is blocked, and the blockage will inevitably [cause the rivers to] dry up. The country must rely on mountains and rivers. The rivers are depleted, and the mountains are bound to collapse, which is a sign of destruction [17].” The Historical Records Fengchan Book has the following quotation: “Some people say that because Yongzhou has a high terrain and is a blessed place for gods, various shrines are gathered here.” Fengchan (封禅) was a ceremony in which a meritorious emperor repaid the gods of heaven at Tai Mountain (泰山) and Liangfu (梁父), which was interpreted in the book Justice as follows: “Build earth on Tai Mountain as an altar to worship the heaven to repay its kindness, and so it was called Feng (封). Tai Mountain extends under the hill in addition to the ground surface, and contributes to the work of the ground, so it is called Chan (禅) [18].” The king ruled on behalf of heaven and patrolled the world; the mountain gods also patrolled on behalf of the gods of heaven, so sacrifices to heaven and sacrifices to the mountain are often interconnected, reflecting the divine order of heaven and mountains [19]. The mountains in the war scenes mentioned above are not only representations of territory limits but also the object of patrols and sacrifices. In The Book of Rites: Royal Regulations, “The emperor, about to go to war, represents God, and is suitable for holding ceremonies for the battlefront.” Zheng Xuan noted, “Ma (祃) refers to the official who presides over sacrifices, responsible for praying for the army and wishing for a safe and victorious campaign [20].” Zhou Li Chun Guan recorded the duties of Zong Bo: “If the generals of the army have important matters to handle, they will go to the sacrificial site with the officials presiding over the ceremony to carry out the relevant ceremonies [21].” The war and hunting in Han portraits are a symbol of conquest that encompasses the universe and swallows the eight wastelands.

Conclusion

The development of traditional Chinese ornaments in the Han Dynasty was a period of transition. On the one hand, Han art inherited the ritual and missionary functions of pre-Qin plastic arts. On the other hand, social class awareness included a change from collective unconscious art to individual aesthetic consciousness. In the context of rituals and symbols, the Han pictorial style of mountains developed into diversified forms, which also manifested the traditional Chinese natural aesthetic of “mountains and waters flattering the Tao with their shapes.” Mountains are rich in material resources for human beings, and they are necessary conditions for the nurturing of life in the sky. The aesthetics of mountain form and the worship of mountains in the Han Dynasty gave philosophical connotations to the meaning of natural mountains and rivers. The aesthetic sense of swimming in nature and landscapes is embedded in the Han pictorial style of depicting mountains, which developed the natural beauty of landscapes in the Wei and Jin Dynasties. The Han depictions of mountains were an important starting point in the history of natural aesthetics in China.

Modeling fairy mountain mythologies in the Han Dynasty was a rich and diverse tradition; in addition to portrait stones, brick-based depictions of fairy mountains, the Boshan furnaces [43], money trees and other plastic arts, there are often a variety of models of fairy mountains. In Mancheng, Hebei, the Liu Sheng tomb of copper depicted a gold version of the Boshan furnace, with a covered top and the upper part of the furnace plate depicting high and steep mountains in relief, including mountains dotted with deer-chasing hunting scenes. The ceramic Boshan stove in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figure 12) has a Boshan-shaped lid, with layers of mountains stacked on top of the lid, animals perched between the hills, and a hunter chasing his prey through the mountains. A mountain-shaped chandelier was excavated from Fufeng Guanwu Village, Shaanxi. The tall base is molded with a semicircular pattern of overlapping layers, creating the image of rolling hills. The high base of the mountain-shaped chandelier is molded with the peaks of mountains and rivers, and then the figures and animals are pasted on it, creating the atmosphere of a fairy mountain where immortals and precious animals converge.

Famous mountains and rivers were places where the immortals lived in the imagination of the artists of the Han Dynasty, and the aesthetics of mountains and rivers were deeply influenced by contemporary cosmology, which was a concrete manifestation of the creation of life in heaven. The Han people experienced the beauty of the birth of cosmic transportation and transformation in the aesthetics of mountains and rivers.

Ceremonial symbol

Mountains originally belonged to the natural material world, but in traditional culture, they are endowed with many meanings beyond the natural definition. Therefore, mountains are displayed as symbols of humanity in people’s minds [15]. The mountains are called “heaven,” so ancient people believed that high and steep mountains were the gathering place of the gods. Mountains and rivers are the coordinates of the earth. It is said that during the flood control measures implemented by Dayu, he followed the path laid by the mountains to plant trees, laying the foundation for mountains and rivers. The "Dengbao Mountain", (登葆山) “Ling mountain” (灵山), and “Zhao mountain” (肇山) in The Classic of Mountains and Rivers (《山海经》) have the primitive function of connecting the heavens with the universal mountain of witchcraft in tribal celestial rituals.

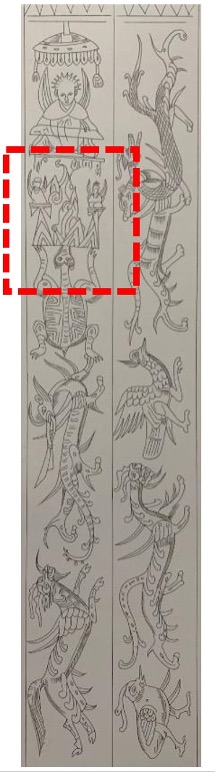

In the excavated materials, the scene of the ascension of the Queen Mother of the West to the immortal realm of the sacred mountain is portrayed. The Queen Mother of the West - Traveling by Cart and Horse is a statue unearthed in North Cave Mountain, Maocun, Tongshan, Xuzhou, Jiangsu Province (Figure 10). It depicts the Queen Mother of the West, the feathered man (羽人), and the Jade Rabbit pounding medicine into pills (玉兔捣药) on the top layer, while the middle two layers are carved with mountain ranges and beasts and beasts playing and dancing. In Yinan, Shandong, the Han tombs contain a room with an octagonal column carved to represent the “pot-shaped mountain” (Figure 11). The picture depicts a giant tortoise on the back of the towering mountain, which should be one of the Kunlun sacred mountains. On the sacred mountain, the Queen Mother of the West is seated; indeed, this kind of “pot-shaped mountain” is closely related to the image of the Queen Mother of the West, consistent with the records of the Kunlun Mountains and the Queen Mother of the West in the literature. The Kunlun Mountain goddess Queen Mother of the West was in charge of torture and safety, and her duties were to supervise severe punishments and the five disabilities of heaven. Liu Xicheng in the Myth of Kunlun and the original phase of the Queen Mother of the West said: “Xiwangmu is a leader of a primitive tribe named Xiwangmu and based in multiple territories such as Yushan (玉山) and Xiwangmu Mountain (西王母山) [35].” In Anqiu, Shandong, on the western wall of the back room of the Han tomb, the picture is divided into two parts, with the upper part of the middle representing “mountains” shaped as four bush-like mountains, with overlapping mountain ranges, grass and trees, and mountain peaks between the curling clouds. The mountain is covered with tigers, leopards, apes, deer, rabbits and other beasts and birds. The left side of the mountain depicts the feathered man and immortal birds and animals. In Zhengzhou, there are Han portrait bricks depicting the Queen Mother of the West sitting in the Kunlun Mountains; the mountain is carved with various kinds of beasts and trees. A hollow brick portrait engraved with the Queen Mother of the West depicted undulating mountains and the Jade Rabbit pounding medicine outside the South Pass in Zhengzhou. In the Han stone carvings found in Tengzhou, Shandong, in Suide, Shanxi, and in Shenmu Dabao, the Western Queen Mother often sits on a Xuan Pu (悬圃), which refers to the Kunlun Mountains.

Regarding the scene of the immortal world in the Kunlun Mountains, Huai Nan Zi - Topography Training contains the following passage: “Yu is to rest the earth to fill the flood as a famous mountain, digging the Kunlun Hollow below the ground, there are nine weights of the city of Zengcheng; its height is 10,000 thousand miles, a hundred and fourteen paces and two feet and six inches. On top of the wood harvest, its major trees include the bead tree, jade tree, Xuan tree, and immortality tree in its west; Sha Tong and Luanggan are in its east. The Jiang tree is in its south, and the Bi tree and Yao tree are in its north… It is said that on the top of the Kunlun Mountains, there is a peak that one can climb twice as high as the other mountains, which is called Liangfeng Mountain. Climbing this mountain can save one’s life; climb twice as high, and you will reach Hangpu Mountain. Climbing to this mountain will enable the climber to receive the help of gods and call for wind and rain. Climbing double the distance again, and you will reach the sky. Once here, you will become an immortal, and this is also the place where the Tai Emperor resides [36].” Tian Wen asked, “Where is Kunlun Xuan Pu? What is the height of Zengcheng [37]?” Shi Yi Ji contains the following passage, “The Kunlun Mountains encompass the land of Kunling, surpassing the positions of the sun and moon. The mountain is nine-tiered, with each tier spanning ten thousand miles [38].” Hetu Kuo Di Xiang contain the following passage: “The Kunlun Mountains are the heavenly pillars of air reaching up to the sky.” “The Kunlun Mountains are the center of the human world. Underground are eight pillars, each spanning ten thousand miles wide, totaling three thousand six hundred units, interlocking, and supporting the famous mountains and rivers, connecting various caverns [39].”