Highlighting the Artistic Status of Shanchuan Woodblock Prints

In the history of ancient Chinese painting, apart from paintings on silk and rice paper, there are numerous murals left in caves, temples, and tombs, as well as a large number of woodblock prints preserved in ancient books throughout the ages. Murals and woodblock prints are two important poles in the history of painting, and their quantity and scale cannot be underestimated. Murals have long been neglected and downplayed in the study of Chinese painting history and theory, and even though artists like Gu Kaizhi and Wu Daozi were outstanding representatives of mural creation at the time, the fundamental artistic status and academic influence of murals have not been elevated. Ancient Chinese woodblock prints have also faced a similar situation. Even though renowned artists like Qiu Ying, Tang Yin, Chen Hongshou, Jian Jiang, Mei Qing, and Xiao Yuncong joined the creative team, it still did not change the weak position of ancient woodblock prints. The historical achievements and artistic value of these prints have not been fully recognized and adequately valued.

Investigating the reasons for this, it is mainly because ancient China revered the literati and scholar-officials, and thus promoted literati painting and scholar-official painting. Meanwhile, professional painters and craftsmen were somewhat looked down upon, and their artistic works were not recognized by the literati. Qing Dynasty artist Gong Xian discussed the difference between “tu” (图, illustration) and “hua” (画, painting) in the inscription of his work “Clouds Deep in the Trees” (《云来深树图》): “In ancient times, there were illustrations but no paintings. Illustrations are about depicting objects, people, and events accurately, while paintings need not be [3].” Gong Xian believed that “in ancient times, there were illustrations but no paintings,” and “illustrations” should be based on reality. “If required to depict events, it would be very common, and it seems that it cannot be avoided before the Jing and Guan periods [3].” Therefore, he praised the freehand “paintings” after Dong Yuan, “With objects such as clouds, mountains, misty trees, perilous rocks, cold springs, wooden bridges, and wild houses, people can be present or absent. After Dong Yuan, all the impurities were washed away, and within a small space, it seemed like a thousand miles [3].” From this, it can be seen that whether it is ancient maps or Shanchuan woodblock prints based on realistic geography, they are not accepted by the freehand aesthetics system dominated by literati painting due to their indicative functions of “depicting events according to requirements.”

However, from the perspective of art history, we cannot deny the landscape paintings before the Jing and Guan periods, nor can we use literati paintings to negate Shanchuan woodblock prints. Both have the attributes and characteristics of painting and are fundamentally different from the drawing and presentation methods of maps. Moreover, ancient Chinese maps were subject to limitations in surveying and mapping technology, and often relied more on human depiction, thus possessing a certain degree of humanism and artistic quality. As a result, this ancient map style is also significantly different from today’s geographic maps.

In addition, there is another reason: in ancient times, the process of creating woodblock prints involved completing the painting draft, handing it over to the engraver to carve the woodblock, and finally having the printer produce the print. Ancient woodblock prints, like ancient stele calligraphy, are considered second or third-hand works, and are thought to have lost the value of the original artwork. For example, after a calligrapher’s work is written, it is then carved into stone or rubbings are made on paper by others. The calligraphy transferred onto the stone by craftsmen inevitably differs from the original work of the calligrapher. Therefore, the Song Dynasty calligrapher Mi Fu stated in his “Haiyue Mingyan”: “Stone carvings cannot be learned. Even if one asks someone to carve their own writing, it is no longer their own work. Thus, it is necessary to observe the true works to appreciate them [4].”

However, stele inscriptions ultimately originate from the true calligraphic works, and if the engraver’s skills are exquisite, the carved strokes can also faithfully reproduce the calligrapher’s brushwork. Therefore, the study of steles has always been an important method for learning calligraphy. Based on the characteristics of carving, weathering, and wear in stele calligraphy, new brush techniques have been created to express this “metal and stone charm.” As for ancient woodblock prints, their artistic value can also be realized through the skills of the engravers and printers, and they can create and pursue the unique artistic taste formed by woodblock carving and printing. Therefore, the art of ancient woodblock prints can be considered akin to the study of steles in ancient calligraphy, serving as not only an important engraving method for painting art but also a special category of painting art.

In the 1930s, under the advocacy and promotion of people like Lu Xun, China began the development of modern printmaking. Today, despite the significant impact of advanced photography and printing techniques, printmaking, with its unique expressive capabilities and styles, still ranks as one of the three major types of art in higher fine art education systems, along with traditional Chinese painting and oil painting. The “national oil print and sculpture” tradition is part of the curriculum in most art academies in China. This shows that printmaking holds a significant position in the field of fine arts and deserves full recognition and research to promote the deserved status of printmaking art.

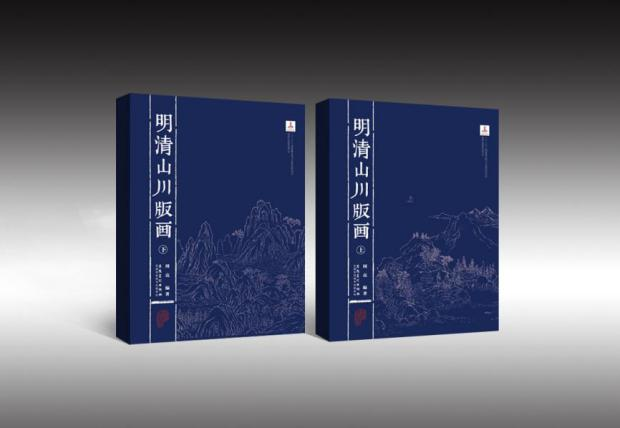

“Ming and Qing Dynasty Landscape Woodblock Prints” brings together a comprehensive collection of ancient print materials, many of which are precious and unique. For example, the “Scenic Spots of Lakes and Mountains” from the Ming Dynasty Wanli period, held in the French National Library, is a rare overseas edition. The book uses five-color overprinting and features exquisite engravings, combining poetry, calligraphy, and painting to showcase the ten major scenic spots of Wushan in Hangzhou. “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties” primarily includes landscape print illustrations from the gazetteers of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, which consist of prefecture gazetteers, provincial gazetteers, county gazetteers, mountain gazetteers, and temple gazetteers. Mountain and temple gazetteers generally contain landscape print illustrations of mountains or mountain backgrounds, while prefecture, provincial, and county gazetteers use landscape woodblock prints to depict the local topography. Professor Zhou Liang selected more than 500 print illustrations from over 270 editions among more than 400 ancient books to form the content of the book. “Ming and Qing Dynasty Landscape Woodblock Prints” is a further refined selection based on a comprehensive understanding of the materials. Important ancient book editions are included, and different versions of the same content are also collected for comparison. A few of the landscape print illustrations are not from gazetteers, but serve to embellish and enrich the content of the book. The book’s content is extensive and meticulous, with multidisciplinary research value in history, geography, and art.

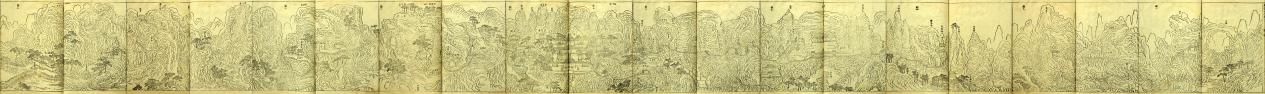

“Ming and Qing Landscape Woodblock Prints” focuses on landscape-themed prints, further exploring the multi-page continuous format in printmaking. This is a long-overlooked and nearly submerged type of print, similar to the long-scroll painting style of ancient China, representing the highest artistic form of ancient printmaking. Although the number of works is limited, the artistic quality is exceptional. In the past, people were mainly accustomed to single-sided and double-sided print layouts, which fit the basic form of book page illustrations and were widely found in ancient religious scriptures, Confucian writings, dramas, novels, local histories, painting manuals, and technical and agricultural books. The multi-page continuous print format is more suitable for landscape-themed prints, depicting the continuous atmosphere of the vast landscapes. “Ming and Qing Landscape Woodblock Prints” focuses on and excavates the multi-page continuous landscape woodblock prints attached to local records, filling a significant gap in the traditional printmaking field.

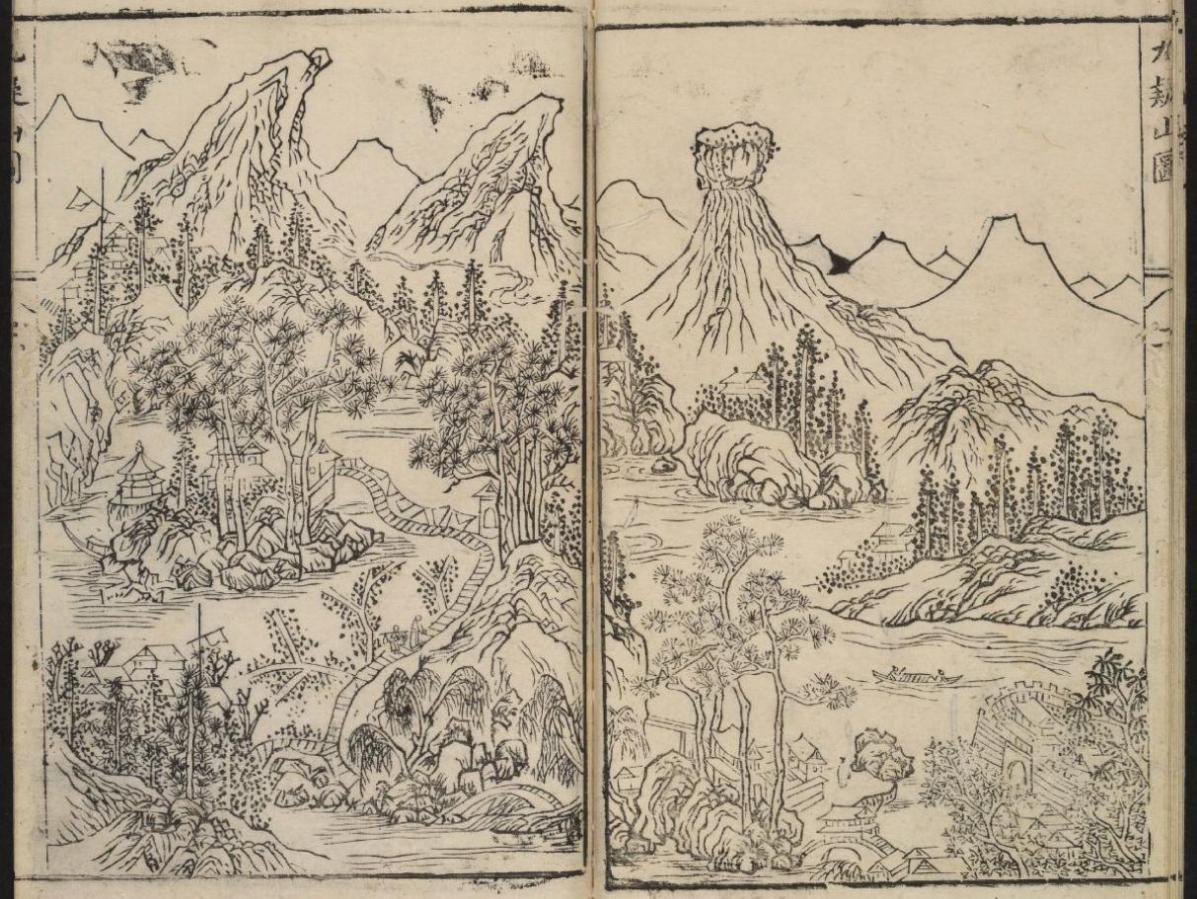

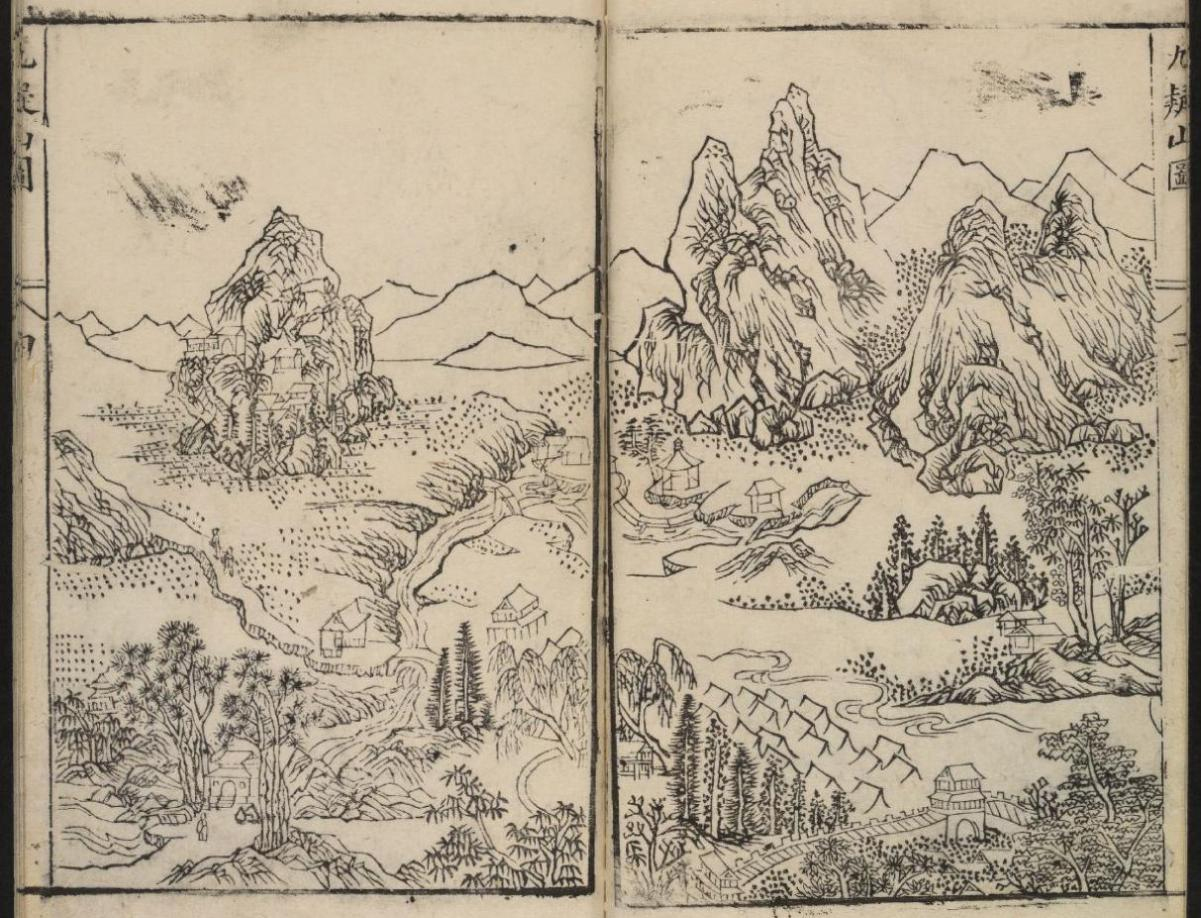

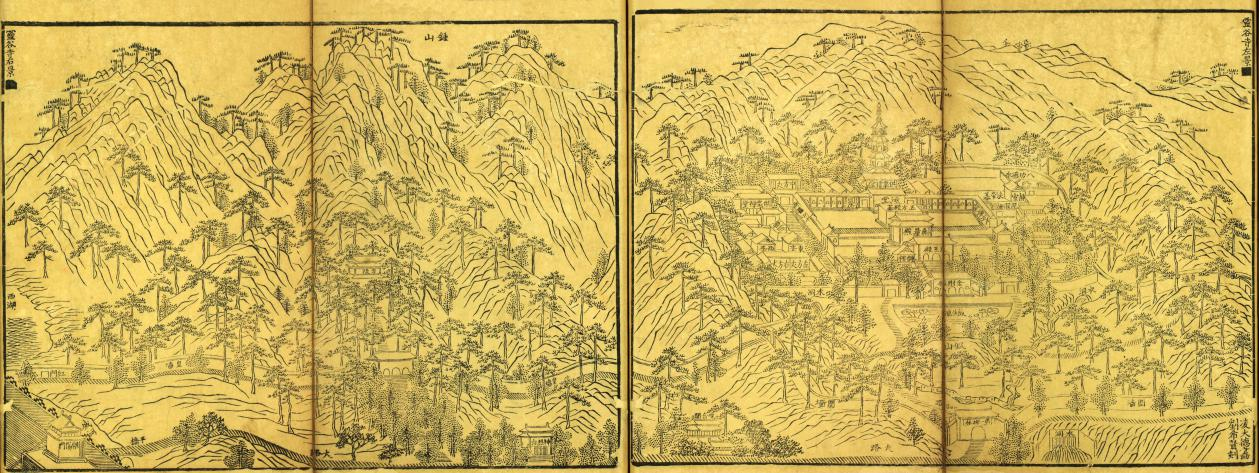

Multi-page continuous landscape woodblock prints are rarely found in local records such as prefecture, state, and county annals but are mainly found in mountain and temple records within these local records. For example, the Ming Dynasty “Qiyun Mountain Records” contains 20 pages of continuous landscape print illustrations (Figure 4), and the Ming Dynasty “Putuo Mountain Records” contains 27 pages of continuous landscape print illustrations. Temples are often part of the mountains, so they are also included in the landscape woodblock prints category. For instance, the “Lushan Temple Records” published during the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty has four pages of continuous landscape print illustrations, and the Qing Dynasty “Wulin Lingyin Temple Records” contains 24 pages of continuous landscape print illustrations.

Compared to single-sided and double-sided layouts, multi-page continuous prints can be connected to form long scroll prints, possessing the composition and expression characteristics of long scrolls. Originating from paintings, formed through engraving, and completed by printing, these multi-page continuous landscape woodblock prints are either simple and elegant or exquisitely graceful. The landscapes, geography, and local customs can be appreciated, viewed, inhabited, and explored. The layout of the landscapes in the multi-page continuous prints refers to the geographical distribution, emphasizing rhythm and rhyme, creating a more expansive and long-term visual perspective, and possessing the artistic function of “reclining travel.” As Professor Zhou Liang said: “Its structural integrity fully embodies the various characteristics of long scrolls, such as prologue, unfolding, climax, relaxation, rhythm, repetition, and finale. The viewer can change along with the fluctuations of the painting, be brought into an immersive space, and be placed in a realm where both the self and the object are forgotten [5].” The “immersive space” and the “realm of self-object forgetting” are the artistic world of “reclining travel.” Therefore, the inclusion and research of multi-page continuous landscape woodblock prints are important supports and clear evidence for the independent value of ancient printmaking art, which helps to elevate the art historical status of landscape woodblock prints and ancient printmaking art and promote the artistic independence and academic research of ancient printmaking.

The Classification, Artistic Status, and Extended Significance of Chinese Landscape Woodblock Prints-An Elaboration on the Value of the Collection “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties”

by Yang Xiangmin *

Art Research Institute, Nanjing Art Institute, Nanjing, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2023, 1(1), 1-13; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2023.0802a1

Received: July 17, 2023 | Accepted: July 28, 2023 | Published: August 2, 2023

Introduction

In ancient China, with the support of advanced printing technology, traditional printmaking has a long history and has achieved brilliant accomplishments, becoming an important medium for the dissemination of culture and art. Prints not only circulated, were collected, and published among different cultural strata but also took the form of New Year pictures, images of the God of Wealth, Door Gods, and Kitchen Gods, deeply ingrained and popularized in folk customs and festivals among the general public. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, traditional printmaking reached its peak, just like the novels of the same period, having an influence on the world that was difficult for other art forms like Chinese painting to match. For example, Chinese prints directly influenced Japanese ukiyo-e art, which in turn influenced the development of Western art.

Professor Zhou Liang, a renowned scholar in the field of ancient Chinese prints, recently published the collection “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties” (Figure 1), which for the first time treats landscape woodblock prints as a formal category in printmaking, systematically organizing and comprehensively presenting them. The author presents the development and evolution of landscape woodblock prints chronologically and geographically, showcasing regional differences. This unprecedented collection and systematic organization of landscape woodblock prints hold new significance and value that merit our attention.

Establishing the Art Category of Landscape Woodblock Prints

By referring to the development history of Chinese painting categories, we can draw useful lessons for ancient printmaking. Early Chinese paintings focused on figures, with landscapes emerging and birds and flowers budding during the Six Dynasties. The subjects then gradually diversified and were categorized. During the Tang Dynasty, Zhang Yanyuan’s “Records of Famous Paintings Through the Ages” divided painting into six categories: figures, buildings, landscapes, horse-riding, spirits, and birds and flowers. The Northern Song Dynasty’s “Xuanhe Painting Catalogue” divided painting into ten categories: Taoism and Buddhism, figures, palaces, ethnic groups, dragons and fish, landscapes, animals, birds and flowers, ink bamboo, and fruits and vegetables. By the Yuan Dynasty, paintings were divided into thirteen categories, although not all of them were listed in order. In the Ming Dynasty, Tao Zongyi’s “Chu Geng Lu” listed the thirteen categories in detail: Buddha and Bodhisattva images, Jade Emperor and King Dao images, Vajra, spirits, Arhats, holy monks, wind and clouds, dragons and tigers, past life figures, whole landscapes, flowers and bamboo, plumage, wild mules and moving animals, human activities, boundary paintings, towers and pavilions, all side-births, farming and weaving, and engraved blue and green. Looking at the historical evolution of Chinese painting, it is evident that the richness and development of its typological system are important manifestations of the development of Chinese painting art.

Ancient Chinese prints began to appear during the Sui and Tang dynasties, and until the Five Dynasties, Song, and Yuan periods, they were mainly used as illustrations in Buddhist scriptures, primarily featuring Buddhist figures. During the Yuan Dynasty, prints of novels and plays also mainly focused on figures. It wasn’t until the Ming and Qing dynasties that figure themes became the primary focus of ancient print art. Unlike Chinese painting, ancient prints never systematically differentiated various categories or had related theoretical research, which may be why they did not achieve the same level of independence, maturity, and development as Chinese painting. However, in today’s writing on the history of ancient prints, we cannot mechanically apply the divisions of Chinese painting and simply categorize prints as landscape woodblock prints, flower and bird prints, or figure prints.

At present, there are five commonly recognized categories of ancient prints, typically based on the perspective of their artistic medium rather than their artistic essence: prints used as illustrations in literature such as plays and novels; religious illustrations in religious scriptures; illustrations for skill teaching in painting and ink collections; landscape illustrations in geographical records; and illustrated stories and figure collections. This demonstrates that for a long time, the industry has not paid attention to the categorization of ancient print art and has lacked relevant theoretical research. The customary use of categories like play prints and novel prints reveals the lack of independence of print art and its existence as an adjunct. In summary, ancient Chinese prints have a rich history and varied categorization, but it is important not to oversimplify their classification. Recognizing the nuances in their categorization can provide a more comprehensive understanding of ancient print art and its development.

Throughout history, mountain and river prints have been one of the categories within ancient Chinese printmaking. However, this category has not received significant attention until Professor Zhou Liang proposed the concept of mountain and river prints, which is a classification based on the essence of ancient printmaking art. This classification highlights the independent value of ancient printmaking art, as compared to drama prints and novel prints. In 1959, Mr. Wang Qi published an article titled “Ancient Chinese Landscape Woodblock Prints” in the fourth issue of Art Research. However, the term “landscape woodblock prints” did not gain traction, and the reason for this is similar to the distinction between “landscape painting” in the West and “landscape painting” in China. Western landscape paintings, such as Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise,” depict realistic natural scenes, while Chinese “shan shui” paintings, such as Huang Gongwang’s “Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains,” bear little resemblance to real landscapes. As a result, the term “landscape woodblock prints” is not suitable, and it is also not appropriate to simply rename “landscape woodblock prints” as “shan shui prints.”

The use of the term “mountain and river prints” rather than “landscape woodblock prints” in the context of Ming and Qing prints is very appropriate. These mountain and river prints correspond to real mountain and river geography, as they are illustrations of geographical features found in regional records, such as “Huangshan Annals,” “West Lake Annals,” “Ode to Jinling,” “Guanzhong Scenic Spot Atlas,” and “Famous Mountains and Scenic Sites of the World.” Mountain and river prints serve both as indicators of mountain and river geography and as artistic works with the characteristics of landscape paintings. They are a unique form of artwork that lies between the two and draws on the strengths of both.

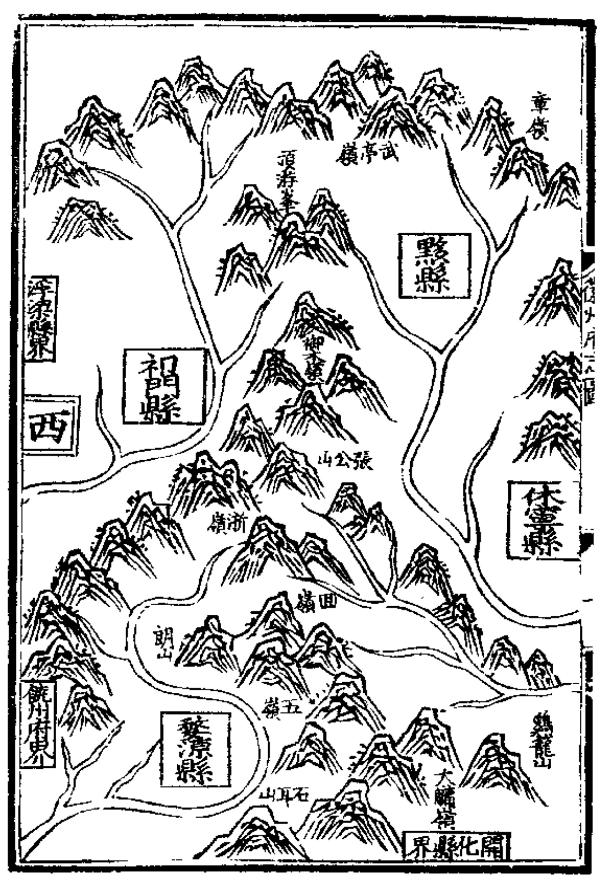

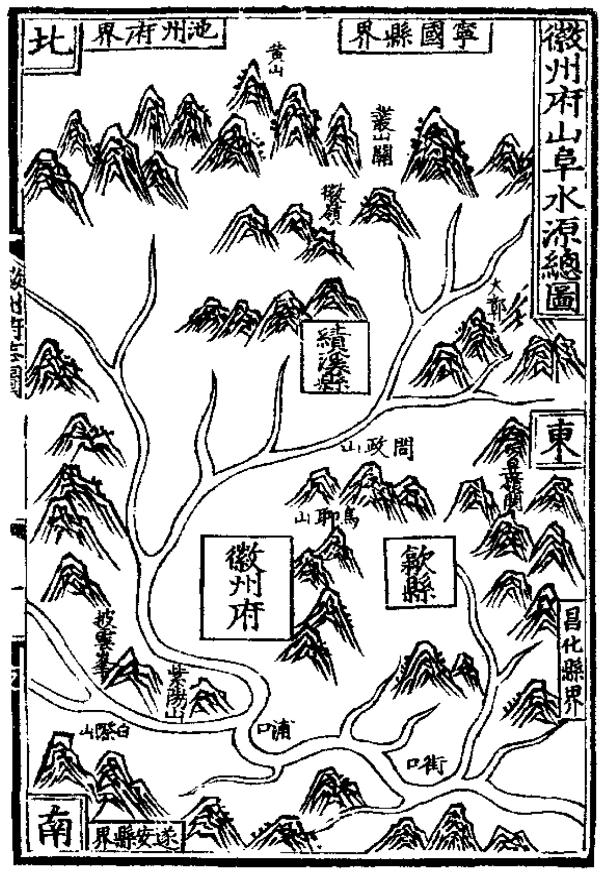

In reviewing “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties,” we also noticed that the works included in the book span a large time and space, involving numerous painters, engravers, and printers of varying skill levels. Works of different quality levels exhibit different tendencies. Outstanding mountain and river prints are closer to landscape art, such as the “Jiuyi Mountain Map” (Figure 2) in the “Jiuyi Mountain Annals” during the Chongzhen period of the Ming Dynasty, and the illustrations “Quyuan Fenghe” and “Shuangfeng Chaoyun” in the “West Lake Annals Compilation” during the Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty. Ordinary mountain and river prints, on the other hand, bear more resemblance to maps, such as the “Wu Yue Chu Map” in the “Ancient and Modern Jinling Map Research” during the Zhengde period of the Ming Dynasty, the “Shidai Sijing Map” in the “Chizhou Prefecture Annals” during the Jiajing period of the Ming Dynasty, and the “Huizhou Prefecture Mountains and Water Sources General Map” (Figure 3) in the “Huizhou Prefecture Annals” during the Hongzhi period of the Ming Dynasty.

In the early stages of Chinese landscape painting, when it was still immature, it also bore traces of maps, and mountain and river prints demonstrate a similar developmental process. Ancient prints, as illustrations in books, had to be both informative and aesthetically pleasing, which are objective rules and internal pursuits. During the Southern and Northern Dynasties, Wang Wei mentioned in “Xu Hua” (Preface on Painting): “The ancient people’s painting was not to delineate city boundaries, distinguish provinces, mark towns, or draw rivers [1].” This can refer to both landscape painting and the creative pursuit of mountain and river prints. As Professor Zhou Liang pointed out: “A good illustration must meet the basic requirements for artistic appreciation while fulfilling its indicative function [2].” It is evident that the aesthetic qualities of mountain and river prints are both an inherent requirement for their development and an important sign of their maturity and perfection.

Abstract

The collection “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties” treats landscape woodblock prints as a distinct category, systematically organizing and presenting them in chronological order to showcase their development and evolution, and geographically to reveal regional differences. This approach promotes the independence of traditional Chinese prints in art history, elevating their status and influence. In Chinese history, the division of labor and cooperation in printmaking allowed both literati and professional painters to participate in print creation, contributing to the improvement of the art form. Landscape woodblock prints not only have the indicative function of landscape maps but also possess the artistic characteristics of landscape paintings, representing a pictorial form that bridges and draws from both. Ancient landscape woodblock prints and landscape paintings complement each other and provide mutual support in both creation and research. Landscape woodblock prints are closely related to the local geography and serve as important supporting materials for advancing the study of artistic geography. Compared to landscape paintings, they hold greater significance and value in the field of artistic geography.

Funding

This research was supported by the Major Project of Art Studies supported by the National Social Science Fund of China in 2020 – “Research on Chinese Painting Studies” (Project number: 20ZD12).

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

References

1. Jianhua Yu, A Collection of Ancient Chinese Painting Theories (Volume 2) (Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2004), 585-586.

2. Liang Zhou, “Research on Landscape Woodblock Prints in Chorography of HuiZhou in Kangxi Period of Oing Dynasty,” Journal of Anhui Normal University (Hum. & Soc. Sci.) 42, no. 2(2014): 166-172. [cnki]

3. Lian Zhang and Hironobu Kohara, eds., A Collection of Essays on Literati Painting and the Northern and Southern Schools (Shanghai Calligraphy and Painting Publishing House, 1989), 32.

4. Mi Fu, “Haiyue Mingyan”, in Mi Fu Collection, ed. Huang Zhengyu and Wang Xincha (Wuhan: Hubei Education Press, 2002), 204.

5. Liang Zhou, “Preliminary Study of Multipage Landscape Woodblock Prints in Ming and Qing Dynasties,” Creation and Design, no. 5 (2018), 47-55. [cnki]

6. Danna, Philosophy of Art, trans. Fu Lei. (Beijing: Sanlian Bookstore, 2016), 42.

7. Hao Zhang, Art Geography - Research on the Phenomenon of Contemporary Chinese Art (Hangzhou: China Academy of Fine Arts Press, 2015), 31.

© 2023 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Yang Xiangmin, "The Classification, Artistic Status, and Extended Significance of Chinese Landscape Woodblock Prints-An Elaboration on the Value of the Collection “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties”." JACAC 1, no.1 (2023): 1-13.

AMA Style

Yang Xiangmin. The Classification, Artistic Status, and Extended Significance of Chinese Landscape Woodblock Prints-An Elaboration on the Value of the Collection “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties”. JACAC. 2023; 1(1): 1-13.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Establishing the Art Category of Landscape Woodblock Prints

- Highlighting the Artistic Status of Shanchuan Woodblock Prints

- Extending the Artistic Influence of Landscape Woodblock Prints

- Conclusion

- Conflicts of Interest

- Funding

- References

Extending the Artistic Influence of Landscape Woodblock Prints

Ancient landscape woodblock prints and landscape painting art mutually reflect each other, forming a reciprocal support in creation and research.

The manufacturing process of ancient prints integrates painting, engraving, and printing techniques, with painters, engravers, and printers collaborating in a division of labor. The primary focus is still on the level of painting. The central concept of printmaking is ultimately “painting,” with engraving and printing established based on the foundation of the painting draft. Today’s printmakers need to complete painting, engraving, and printing independently, with the painting remaining as the core content of creation and presentation. Landscape woodblock prints should summarize and refine the techniques of landscape painting, presenting a more fundamental visual representation.

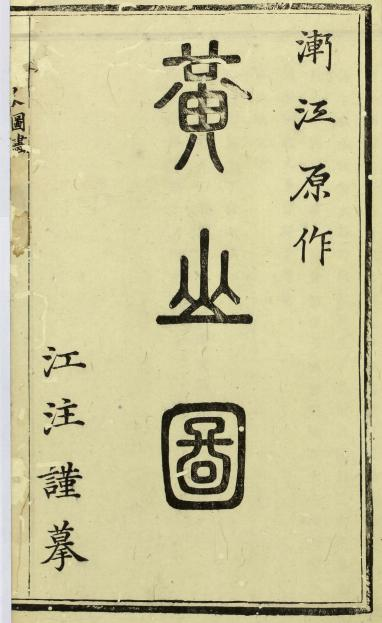

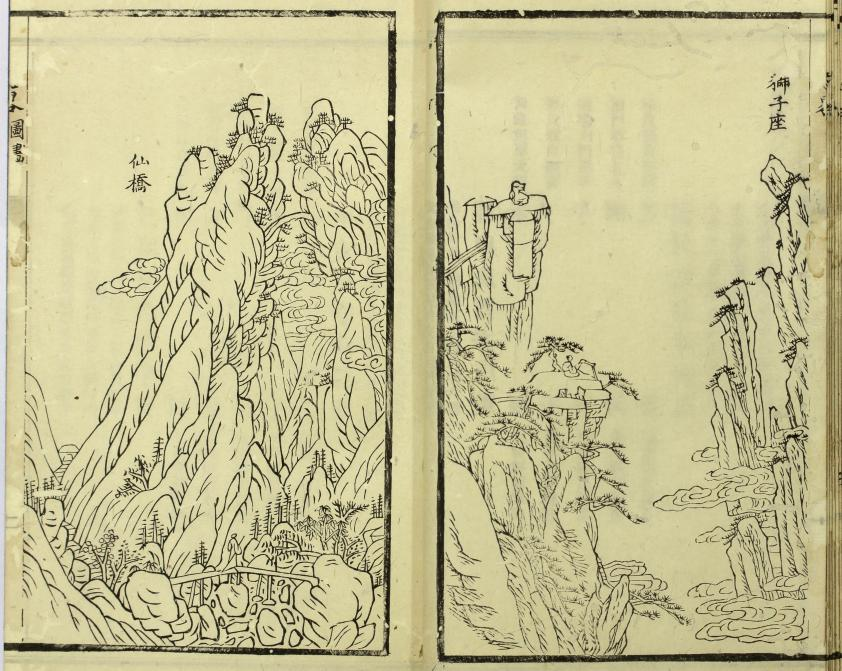

The cooperative division of labor system in ancient printmaking in Chinese history has the advantage of allowing literati painters and professional painters to join the printmaking creation team more easily. Painters joined the creation of ancient prints as early as the Song Dynasty, and this became more common in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Works by painters such as Qiu Ying, Tang Yin, Chen Hongshou, Gu Zhengyi, Jian Jiang, Mei Qing, Xiao Yuncong, Xue Zhuang, Chen Wei, Shao Huang, Jiang Zhu, Wang Ziqin, and Xu Que have been passed down to the present. Some works, although not from contemporary masters, have benefited from historical masters. For example, the landscape woodblock prints in the “Jiuhua Mountain Records” published in the 29th year of Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty are finely drawn and engraved, and the inscriptions indicate that they imitate the painting techniques of Tang, Song, and Yuan Dynasty painters such as Li Sixun, Liu Songnian, Li Cheng, and Huang Heshanqiao. The “Huangshan Annals” published in the 31st year of Kangxi features Huangshan paintings directly from the early Qing master Jian Jiang, with the inscription “painted by Qing Jian Jiang, imitated by Jiang Zhu.” However, the painting style is quite different from Jian Jiang’s landscape paintings (Figure 5). Jian Jiang’s landscape paintings often use folded belt textures, with hard turns and a simple, distant, sparse, and cold atmosphere. But the paintings in the “Huangshan Annals,” such as “Ciguang Temple,” “Wenshu Institute,” “Immortal Bridge,” and “Lion’s Seat,” have curved lines forming dynamic movements, creating a passionate and unrestrained momentum. The direct or indirect involvement of some painting masters in printmaking contributes to a significant improvement in the artistic quality of ancient prints, forming an independent artistic appreciation value.

Traditional Chinese painting supported printmaking, and printmaking in turn nourished traditional Chinese painting. For ancient painters, engraving and printing prints was the only way to publish and distribute their works, thus realizing the mass reproduction and widespread dissemination of paintings. Landscape print illustrations in local records, mountain records, and other documents objectively required painters to “learn from nature” and “search for unique peaks to draft,” which, in turn, promoted the improvement of painters’ skills and the formation of painting styles. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, many print works with Huangshan as the main theme were published and engraved in Huizhou. Painters involved in the process, such as Jian Jiang, Mei Qing, Ding Yunpeng, and Li Liufang, created a landscape painting school in the field of traditional Chinese painting with Huangshan as the main subject. Both the Huangshan School and the Xin’an School of painting took the landscapes of Huizhou, especially Huangshan, as their primary creative themes. Prints and traditional Chinese paintings of Huangshan can mutually reflect each other, forming many common landscape imagery characteristics.

Some works included in “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties” can even directly correspond to famous art history pieces, forming a beneficial reference between the two. For example, the “Licheng County Records” (published by You Sheng Tang in the twelfth year of Chongzhen of the Ming Dynasty, 1639) in the collection of the Library of Congress in the United States contains a two-page print illustration called “Quehua Misty Rain Picture” (Figure 6), which depicts the same scene and shares the same perspective as Yuan Dynasty master painter Zhao Mengfu’s “Autumn Colors of Quehua.” The two distant mountain peaks on the left and right rise abruptly, with the round flat top of Que Mountain in the left foreground and the steep peak of Hua Mountain in the right foreground, surrounded by plains and islets, trees, and houses. The landscape print “Quehua Misty Rain Picture” leaves more space in the foreground for land, with richer content such as city walls, pavilions, willow trees, and rivers, supplementing the information not reflected in the Chinese painting “Autumn Colors of Quehua.”

Landscape woodblock prints in local records are important supporting materials for advancing the study of artistic geography, and they have more significance and value in artistic geography than landscape paintings.

The historical background and geographical environment in which artists live, that is, the dimensions of time and space, profoundly influence artistic creation activities. Winkelmann’s “History of Ancient Art” advocates studying art as an organic whole existing in time and space rather than as isolated works. The historical background of art production is an important factor in art history research, while the geographical environment of art production is an important content of artistic geography exploration.

Based on artistic geography, we pay more attention to identifying regional art, such as the “Yuan Four Masters,” “Ming Four Masters,” “Qing Four Kings,” “Qing Four Monks,” etc., which are actually groups of painters concentrated in the Jiangnan Wuyue region. The painting styles and aesthetic tastes produced in this region also have regional characteristics, so they should not represent the entire national and historical artistic landscape. Northern artists, such as Fu Shan from Taiyuan in Shanxi, Wang Duo from Mengjin in Henan, and Jiao Bingzhen from Jining in Shandong, present a different artistic atmosphere from the south.

Compared with other types of painting images in art history, the works collected in “Landscape Woodblock Prints of the Ming and Qing Dynasties” mainly come from geographical local records, so they have more characteristics of artistic geography. These landscape woodblock prints involve many provinces such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Shandong, Shanxi, Henan, Hebei, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Guangdong, Fujian, and Taiwan. They cover famous mountains and rivers, hills and plains, lakes and land, as well as islands and bays. Such diverse artistic expression objects, ranging from the south to the north, have led to adaptable artistic expression techniques and distinctive artistic expression styles. These specific local customs and living environments, of course, also shape the artists.

One region’s land and water nurture its people, its artists, and its artworks. From the perspective of art geography, the relationship between people and the land is an aspect of exploring personality aesthetics and the origin of art. Archaeologist De Quincey once proposed the “theory of context,” which believes that the original function of an artwork and its place of origin are inseparable. In his book “Philosophy of Art,” Danna considers race, environment, and time as the “three elements” of art, which are the driving forces for the occurrence, development, prosperity, change, and decline of art. For art production, race is the “internal driving force” of the creative subject, environment is the “external driving force” in spatial dimensions, and time is the “acquired driving force” in temporal dimensions. “The creation of a work depends on the spirit of the times and the surrounding customs [6].” Art geography focuses on the “external driving force” of environment in spatial dimensions, and the 19th-century prevalent environmental determinism fully elaborates on this “external driving force”: “The material environment and natural environment determine or influence the human world, including racial physique, national character, social life, state form, and cultural ideas. Climate, terrain, soil, and vegetation play important roles in the formation of national cultural characteristics [7].”

Maps representing geography have a realistic orientation, while landscape paintings representing art have a spiritual orientation. Landscape woodblock prints combine the strengths of both, achieving their own significance and value in art geography. Several books from the Ming Dynasty’s Tianqi and Chongzhen periods, such as “Ode to Jinling Map,” “Ancient and Modern Jinling Map,” and “Jinling Buddhist Temple Records” (Figure 7), contain many landscape print illustrations that present the ancient Nanjing’s topography and cultural landscape. Nanjing, with its strategic location and rich Buddhist culture, has many famous sites clearly marked on landscape woodblock prints, such as Qixia Mountain, Qixia Temple, Zhongshan, Linggu Temple, Tianyin Mountain, Dinglin Temple, Ming City Wall, Ming Xiaoling, Xuanwu Lake, Qinhuai River, Yuhuatai, and Shitou City. As someone who has studied and worked in Nanjing for a long time, I often visit or encounter these places and can easily find a one-to-one correspondence between these real-life scenes and the historical images in ancient books. It can be said that the landscape woodblock prints in local records are artistic works that grow and construct from the local land.

Conclusion

In summary, the collection and study of Ming and Qing landscape woodblock prints specialize in a particular art form, achieving the most comprehensive and systematic compilation of landscape woodblock prints in history. This book “Ming and Qing Landscape Woodblock Prints” lays the foundation for the specialized study of landscape woodblock prints and provides a reference for future research on the history of printmaking. The study of Ming and Qing landscape woodblock prints not only helps promote the independence of Chinese traditional ancient printmaking art, but also enhances its position and influence in art history, benefiting the research and creation of Chinese landscape painting. As illustrations in Ming and Qing local records, landscape woodblock prints can form a mutual verification with historical records, possessing valuable research value in art geography.

Lates articles