A Study on the Narrative Characteristics of Folk Art: A Case Study of Jin-Style Painted Festival Towers as Intangible Cultural Heritage

by Yuyao Zhao *

1 Tianshi College, Tianjin, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2025, 3(2), 44-66; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2025.1222a14

Received: September 27, 2025 | Accepted: November 29, 2025 | Published: December 22, 2025

Introduction

Jin-style painted festival towers (晋式彩楼) constitute a form of folk handicraft that combines both artistic and technical qualities and represents a distinctive category of folk art found across much of Shanxi Province. Owing to their unique handcrafted techniques and their conformity with widely shared vernacular aesthetic preferences, Jin-style painted festival towers differ markedly from other forms of folk art in both formal modeling and chromatic appearance. In the Qingxu area of Shanxi, Jin-style painted festival towers were inscribed in 2011 on the National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage as part of the third batch of traditional fine arts categories.

According to the China Intangible Cultural Heritage Network, painted gate towers (彩门楼) constitute the only existing artistic form of gate-tower construction in China, occupying an exceptionally prominent position within the broader spectrum of gate-tower arts nationwide. As such, they possess considerable historical, scholarly, and economic value. Based on available evidence, the prototype of Jin-style painted festival towers can be traced back to the Han dynasty, where they likely originated as temporary, tied-frame canopy structures. The form gradually matured during the Tang dynasty and appears frequently in textual sources such as Tangshi Jishi, The Collected Works of Du Fu, and Biyun Ji.

At the same time, the narrative language of Jin-style painted festival towers is grounded in everyday materiality. This everyday quality allows them, despite their distinctly non-ordinary and ritualized character, to remain closely aligned with daily life through their inherent temporality. Such temporariness also explains why Jin-style painted festival towers appear comparatively coarse when contrasted with industrial products produced under conditions of modern mass manufacturing. Nevertheless, deeply rooted, vernacular aesthetic traditions and modest taste preferences among local communities continue to sustain their high cultural status within folk contexts.

From another perspective, this form of material substitution endows Jin-style painted festival towers with a certain rawness and ruggedness. Particularly under the influence of Western cultural frameworks, this folk quality has often been interpreted as an outward manifestation of a “rustic” or “earthy”(土) aesthetic—an expression of sensibilities distinct from elite taste cultures, characterized instead by a rough, unrefined vitality.

2.3. Craft Substitution

From the standpoint of craft production, the technical system of Jin-style painted festival towers functions as a narrative language that re-creates pailou architecture through active subjective intervention. This transformation signals the maturity of the craft system itself, demonstrating artisans’ advanced mastery over materials and their capacity to switch, translate, and reconfigure material types and chromatic schemes with precision [10]. In contrast to the mortise-and-tenon structures, painted ornamentation, and tiled construction techniques characteristic of traditional pailou architecture, Jin-style painted festival towers substitute these processes with techniques such as twisting, binding, and color-wrapping.

When artisans process materials through binding, twisting, and hand-painting, the resulting painted tower becomes estranged from both the original architectural form and the original material properties. This process produces a form of heterogeneity, whereby the reworked architectural image generates associative narrative links in the viewer’s perception. Encountering such a transformed structure naturally activates narrative imagination through its simultaneous familiarity and difference.

2.4. Functional Substitution

The functional substitution characteristic of Jin-style painted festival towers constitutes a narrative language grounded in psychological tension and symbolic conflict with the original functions of pailou architecture. This substitution is predicated upon material transformation, craft substitution, and formal imitation. Together, these narrative strategies produce a magical or fantastical effect distinct from that of the architectural prototype, transforming the painted tower into a spectacle specific to ritual time.

While traditional pailou structures typically function to enhance architectural grandeur, commemorate individuals or events, or demarcate spatial boundaries within urban streetscapes [11], Jin-style painted festival towers serve primarily to amplify atmosphere during ritual occasions. Their function lies not in permanence or commemoration, but in the intensification of ceremonial experience.

Through the interaction of multiple narrative languages, the narrativity of Jin-style painted festival towers becomes multidimensional, reinforcing memory and deepening narrative impact. The completed structure thus acquires heightened tension and psychological resonance. At the same time, this reveals the inherent complexity and contradiction embedded in folk material culture: such artifacts cannot be adequately interpreted or evaluated from a single analytical perspective. The continued vitality of Jin-style painted festival towers in Shanxi and surrounding regions stands as evidence of this complexity.

During processes of construction, display, and viewing, the transformed materials do not appear incongruous within their environments. On the contrary, the narrative mechanisms of Jin-style painted festival towers reactivate memories of traditional festivals and personal life experiences, producing a subtle yet powerful associative linkage.

2.5. Summary

As Aristotle observed, “human beings take pleasure in that which is extraordinary” [12]. Through maintaining both strong affiliations with and marked heterogeneity from pailou architecture, the multiple narrative languages of Jin-style painted festival towers readily evoke vague bodily memories associated with familiar forms. At a subconscious level, viewers are drawn to grasp these partial resemblances, which recall architectural imagery shaped by natural materials, personal memory, functional associations, and embedded folk customs.

From the perspective of material use and formal contour, this narrative language of material and form enables a migration of symbolic meaning that adheres closely to the material conditions of everyday living space. Its effect operates subtly and often without the need for explicit interpretation, achieving a form of implicit narrative transmission embedded within lived experience.

2.2. Material Substitution

The narrative language of materials used in Jin-style painted festival towers is generally more flexible compared to that of the paifang (牌坊, gateway archway) structures. The materials used in paifang buildings typically include wood, brick, tile, and paint; whereas Jin-style painted festival towers primarily employ wooden poles, iron rods, colored paper, and colored fabrics. A notable difference is the transformation of colored fabrics, which undergo the twisting technique, a change in material that reflects the intervention and expression of the craftsmen. This process allows us to experience the rich, dynamic spaces they create.

The open, hollow spaces of Jin-style painting festival towers offer a different sensory experience compared to traditional architecture. In the same areas of both paifang and Jin-style painted festival towers, the visual effects differ significantly. The materials used in paifang buildings, after being combined, present a visual effect that integrates rigorous mechanics and aesthetics (Figure 6). In contrast, the Jin-style painted festival towers present a more casual, free-flowing visual effect (Figure 7). At this point, the colored fabric is no longer just fabric; it becomes the product of the interaction and reworking of materials and human craftsmanship, thus forming a distinct narrative.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- 1. The Narrative Value of Folk Art

- 2. The Narrative Language of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

- 3. Narrative Principles of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

- 4. Narrative Imagery Characteristics of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

- 5. Ritual as Narrative Action: Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

- Conclusion

- Funding

- Acknowledgments

- Conflicts of Interest

- About the Author(s)

- References and Notes

1. The Narrative Value of Folk Art

In The System of Objects, Jean Baudrillard examines why modern individuals are drawn to antiques. He argues that the antique embodies a form of completed time, functioning as a medium that colludes the past with the present and enables individuals to attain a sense of existential completeness within historical development. This observation offers a tentative explanation for the continued vitality of Jin-style painted festival towers in contemporary contexts. Strictly speaking, Jin-style painted festival towers are not “authentic” antiques, nor has their craftsmanship been transmitted unchanged from antiquity to the present. Rather, their techniques have evolved over time through adaptation, fusion, and appropriation, even as they have preserved fundamental visual characteristics. From the perspective of artisans, Jin-style painted festival towers constitute a folk craft system that integrates multiple stylistic forms, skills, and procedural techniques. With a long history and profound cultural depth, they represent a rare form of urban cultural landscape in the contemporary era [7].

At their core, Jin-style painted festival towers serve to intensify the ritual atmosphere of festivals and ceremonies, satisfying popular demands for spectacle at specific temporal moments and offering visual experiences distinct from everyday life. Accordingly, the value and appeal of this form of folk art lie in the narrative qualities underpinning its vitality.

Jin-style painted festival towers are primarily erected during the Spring Festival, weddings, funerals, and other exceptional occasions—temporal moments that this study conceptualizes as ritual time. From the standpoint of popular reception, the narrative experience generated by Jin-style painted festival towers constitutes a key mechanism through which ritual time is elevated from ordinary, secular time. Acting as a mediator between individuals and ritual temporality, the materials, colors, and formal compositions of the painted towers are intrinsically connected to the specific rituals being performed. Within ritual time, artisans and the public collaboratively produce beauty through the staging of ritual and reflect beauty through the unfolding of ritual processes. In this way, the construction of Jin-style painted festival towers reveals—often implicitly—the aesthetic values, conceptions of life, and understandings of temporality embedded in folk art, as well as the significance of ritual time as structured by conventionalized craft systems.

This vitality functions as a paradigmatic force shaping popular conceptions of life, subtly influencing multiple dimensions of everyday existence and forming a narrative schema that structures collective experience. Zhang Gan, in his essay Design as Experience, notes that certain handicrafts granted the status of “intangible cultural heritage” lose their vitality once detached from their original historical contexts, surviving merely under the banner of tradition [8]. At the same time, modern design—by forcefully displacing traditional arts and crafts—has enabled products to reach wider audiences at extremely low costs. Within the currents of modernity, however, the accumulated experiential knowledge of folk art—spanning form, function, and material practice—continues to serve as a vital source of inspiration and nourishment for contemporary art and design [8].

Through this deliberate chromatic binarization, Jin-style painted festival towers distill complex architectural color traditions into a highly legible narrative code. Color thus functions not merely as decoration but as a primary narrative device, immediately signaling the ritual nature, emotional register, and symbolic orientation of the event in which the tower is embedded.

The establishment of chromatic binarization demonstrates that the use of color in Jin-style painted festival towers is by no means arbitrary, but instead follows a clear tendency toward patterned and codified application. The themes conveyed through these color schemes are radically different, as are the spatial atmospheres they generate and the behavioral norms they implicitly prescribe. What emerges is a system of oppositional tonal registers. This binarization reflects a deeper cultural logic in which color is systematically linked to values, beliefs, and layers of social meaning. As such, it represents a manifestation of China’s long-standing tradition of symbolic culture, in which chromatic systems function as carriers of moral order and collective ideology rather than as purely aesthetic choices [13].

3.4. Exterior Transgression and the Narrative Value Orientation of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

Karl Marx once observed that “the spirit feels oppressed under the weight of matter, and this sense of oppression marks the beginning of reverence.” Throughout Chinese history, strict distinctions between imperial and popular material forms were maintained through ritual and architectural regulations. For example, The Book of Rites (礼记) stipulates that the ancestral temples of the Son of Heaven should contain seven halls, those of feudal lords five, those of grand officers three, and those of the shi class only one, alongside detailed prescriptions governing the use of vessels, coffins, and other objects [14]. Similarly, the Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty(明会典) restricted dragon and phoenix motifs exclusively to the imperial palace and royal ancestral temples, while prohibiting ordinary residences from employing dougong brackets or painted decoration, allowing only single-eaved gable-and-hip roofs (单檐硬山顶) in predominantly plain colors.

Against this backdrop, the construction of Jin-style painted festival towers by ordinary people constitutes a deliberate imitation—and symbolic appropriation—of material forms that exceed the boundaries of their own social status. For the people, the temporary nature of these structures renders them far more affordable than permanent architecture, while still enabling the production of visually opulent and imposing effects. As a result, Jin-style painted festival towers become folk artifacts through which wealth is displayed, status is symbolically asserted, and ritual atmosphere is intensified.

Viewed from a broader perspective, this folk-art practice of transgressing traditional ritual hierarchies actively stimulates the evolution of vernacular material culture and expands the scope of sensuous experience in everyday life. Such acts of symbolic overreach serve to release suppressed social desires and channel them into culturally legible forms. In this sense, the exterior transgression embodied by Jin-style painted festival towers constitutes a central value orientation of folk art—one that negotiates between constraint and excess, order and desire, reproduction and subversion [15].

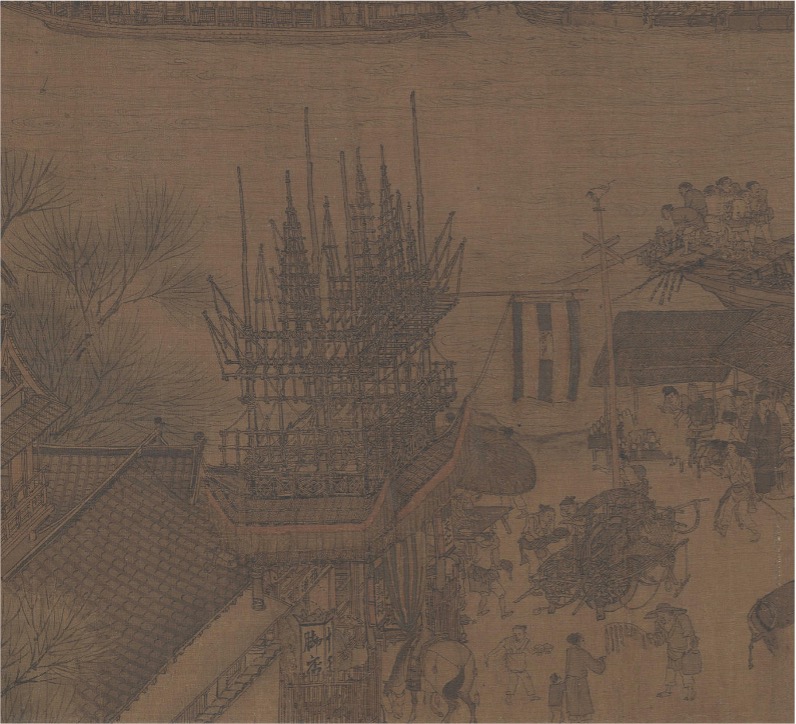

Although the technical capacity for constructing formal pailou structures has become relatively mature in many regions of Shanxi, these techniques have not been fully applied in the construction of Jin-style painted festival towers. Instead, artisans selectively appropriate the symbolic imagery of pailou architecture rather than replicating its structural logic or artistic conventions in their entirety. This mode of architectural borrowing is not unique to Jin-style painted festival towers but is widely observed across other forms of Chinese folk art. Examples include excavated soul jars (魂瓶), ceramic towers, and silver ornaments (Figures 3–5). Such practices reflect a broader characteristic of Chinese folk-art traditions, wherein architectural imagery functions as a transferable symbolic language, embodying shared aesthetic preferences and cultural concepts across diverse material forms.

2. The Narrative Language of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

Plato regarded art as an imitation of reality, while reality itself was understood as an imitation of the world of ideals. Embedded within this theory of mimesis is the notion that art employs specific material media to represent both the forms of the real world and the conceptual realm of imagination; it is within such a “system of imitation” that material culture is able to persist and evolve [9]. Most forms of folk art, to varying degrees, engage in the imitation of objective entities in the real world, or of the archetypal imagery associated with certain categories of artifacts. The narrative language of Jin-style painted festival towers is fundamentally grounded in the formal imitation of traditional Chinese architecture, while simultaneously deploying multiple other narrative strategies.

2.1. Formal Imitation

The overall form and morphological translation of Jin-style painted festival towers can be traced to the conventional typology of traditional pailou (牌楼, decorated archway) architecture (Figure 2). This indicates that the narrative language of Jin-style painted festival towers operates in a subtle and implicit manner, activating subconscious associative links through direct visual perception. Such associations do not require deliberate analysis or conscious interpretation by viewers. Much like how the image of a gourd evokes cultural connotations of fortune and prosperity, or how a sculptural representation of a shepherd boy riding an ox recalls the poetic imagery of “the shepherd boy pointing toward Apricot Blossom Village” [10], the architectural form of the painted tower triggers culturally embedded meanings almost instantaneously.

3. Narrative Principles of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

The distinctive narrative language of Jin-style painted festival towers gives rise to a rich chromatic vocabulary and a visual identity that is both consonant with and divergent from that of traditional pailou architecture. While differing in appearance, their underlying narrative principles—manifested through structure, ornamentation, color, and exterior form—clearly reflect the vernacular character and continuity intrinsic to folk art traditions.

3.1. Structural Simplification as the Foundation of Narrative Art in Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

The decorative articulation of the tower body constitutes a central component of the overall visual system of Jin-style painted festival towers, primarily encompassing columns and their associated ornamental elements. Through the interweaving of multiple narrative strategies, these structures exhibit a markedly simplified configuration when compared to traditional pailou architecture.

In conventional pailou construction, column bases serve practical functions such as moisture resistance, insect prevention, and protection against rodents. Typically carved from stone, the column base functions as an independent architectural component and is structurally subdivided into the base cap, base drum, base waist, and base foot. However, following narrative translation through multiple modes of substitution and abstraction, the column bases of Jin-style painted festival towers undergo substantial simplification or are even entirely omitted.

This process of reduction becomes a key formal condition that allows Jin-style painted festival towers to retain the visual semblance of pailou architecture while discarding its material and structural complexity. For instance, in a traditionally styled Jin-style painted tower constructed in the Pingyao area in 2022, the column bases were rendered as flattened, two-dimensional representations. These were printed onto spray-painted fabric and wrapped around the base of the columns as decorative motifs. Compared with the three-dimensional stone column bases of traditional pailou architecture (Figure 8), this approach significantly simplifies the structural logic of the column base (Figure 9), with the columns making direct contact with the ground.

Abstract

This study aims to reveal the archetypal modes of thinking and aesthetic structures embedded in the collective consciousness of the Chinese people by examining the deep generative logic of folk art. Taking Jin-style painted festival towers (晋式彩楼) as a representative case, the paper focuses on their narrative mechanisms and semiotic system, summarizing their core strategies as four forms of substitution: formal imitation, material substitution, craft substitution, and functional substitution. Together, these four substitutions constitute the fundamental grammar through which Jin-style painted festival towers are translated from everyday utilitarian objects into festive spectacles.

More specifically, the narrative principles of Jin-style painted festival towers can be distilled into four progressive and mutually permeating dimensions. First, structural simplification: through radical omission and geometric abstraction, practical constraints are stripped away, freeing maximal symbolic space for narration and establishing the formal precondition for the entire artistic system. Second, decorative alienation: exaggerated additions and accumulations are imposed upon the simplified framework, transforming decoration from a subordinate element into the dominant visual force and generating the core tension of visual impact. Third, chromatic dualization: symbolic orders are constructed through color oppositions—such as red/yellow and black/white—thereby establishing the tonal polarity of festivity and solemnity. Fourth, visual transgression: by deliberately exceeding vernacular norms in scale, volume, and degrees of extravagance, these structures produce a temporary yet intense inversion of hierarchy and values, sketching a utopian orientation specific to the festive moment.

This paper argues that festivity is not merely an external occasion for the narrative of painted towers, but rather its intrinsic mechanism of completion. Only within the “state of exception” constituted by festive time do the aforementioned substitutions and transgressions attain legitimacy and full meaning; it is also only then that the painted tower truly becomes a “living text” that can be read and experienced. Through an archaeological dissection of this narrative system, the study seeks to demonstrate that folk art is not a marginal residue of “traditional culture,” but a symbolic practice endowed with a high degree of formal self-awareness and latent social critique. Its logic of multiple substitutions not only reveals the aesthetic strategies developed by Chinese communities under conditions of material scarcity—strategies of “achieving more with less” and “replacing the precious with the humble”—but also offers contemporary design a third possibility beyond the one-directional functionalism of modernism and the stylization of consumerism: a narrative design paradigm rooted in festive exceptionality, collective carnival, and the transgression of meaning.

Edited by: Eloise

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Yuyao Zhao, "A Study on the Narrative Characteristics of Folk Art: A Case Study of Jin-Style Painted Festival Towers as Intangible Cultural Heritage." JACAC 3, no.2 (2025): 44-66.

AMA Style

Zhao YY. A Study on the Narrative Characteristics of Folk Art: A Case Study of Jin-Style Painted Festival Towers as Intangible Cultural Heritage. JACAC. 2025; 3(2): 44-66.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References and Notes

1. Zhao, Yuyao, and Zhang Xiaokai. “The evolution of Jin-style painted festival towers as intangible cultural heritage and their interaction with ritual customs.” Journal of Nanjing University of the Arts (Fine Arts & Design Edition), no. 02 (2025): 148–154. [in Chinese]

赵宇耀, 张小开. 非遗晋式彩楼的流变与礼俗互动研究[J]. 南京艺术学院学报(美术与设计版), 2025, (02): 148-154.

2. Sun, Yanfei, and Ding Shan. “Form and meaning: A study on narrative expression in public art of the North and South Beijing subway systems.” Journal of Nanjing University of the Arts (Fine Arts & Design Edition), no. 04 (2016): 109–111. [in Chinese]

孙彦斐, 丁山. 形意表达——论南北二京地铁公共艺术的叙事性研究[J]. 南京艺术学院学报(美术与设计版), 2016, (04): 109-111.

3. Jing, Jianxiong. “Space and cognition: Narrative design of map imagery in children’s picture books.” Journal of Nanjing University of the Arts (Fine Arts & Design Edition), no. 02 (2024): 178–182. [in Chinese]

景剑雄. 空间与认知:儿童绘本中地图图像的叙事性设计[J]. 南京艺术学院学报(美术与设计版), 2024, (02): 178-182.

4. Assmann, A. Spaces of Memory: Forms and Transformations of Cultural Memory. Translated by Lu Pan. Beijing: Peking University Press, 2016. Original work published in German.

阿莱达·阿斯曼著,潘璐译《回忆空间:文化记忆的形式和变迁》,北京大学出版社 2016 年版

5. Long, Diyong. “Image narration: The temporalization of space.” Jiangxi Social Sciences, no. 09 (2007): 39–53. [in Chinese]

龙迪勇. 图像叙事:空间的时间化[J]. 江西社会科学, 2007, (09): 39-53.

6. Liu, Tanru, and Long Diyong. “Schema types, spatio-temporal construction, and narrative functions: An analysis of eavesdropping narratives in Ming dynasty printed opera illustrations.” Xiqu Arts 44, no. 02 (2023): 24–34. [in Chinese]

刘坛茹,龙迪勇.图式类型、时空建构与叙事功能—明代版刻戏曲插图的偷听叙事考察[J]. 戏曲艺术, 2023, 44 (02): 24-34.

7. Zhao, Yuyao. “Exploring the application value of Jin-style painted festival towers in urban scenography from a systems theory perspective.” Creative Design Source, no. 04 (2021): 22–26. [in Chinese]

赵宇耀.基于系统论探讨晋式彩楼在城市造景中的应用价值[J].创意设计源,2021,(04):22-26.

8. Zhang, Gan. “Design as experience.” Zhuangshi (Decoration), no. 01 (2023): 28–33. [in Chinese]

张敢.设计即经验[J]. 装饰,2023,(01):28-33.

9. Zhu, Cunming, and Dou Meng. “New insights into the ‘object-making’ study of Han dynasty ceramic towers: A review of There Are Tall Towers in the Northwest: Tracing the Making of Han Ceramic Architecture by Lan Fang.” Chinese Art Studies, no. 02 (2020): 166–168. [in Chinese]

朱存明,窦萌. 汉代陶楼“造物学”研究的新收获——评兰芳《西北有高楼:汉代陶楼的造物艺术寻踪》[J]. 中国美术研究,2020,(02):166-168.

10. Huang, Houshi. “Figurative design and spatiotemporal substitution: Narrative characteristics in Chinese baijiu bottle design.” Art Panorama, no. 06 (2022): 104–115. [in Chinese]

黄厚石. 具象性设计及其时空置换——中国白酒酒瓶设计中的叙事性特征研究[J]. 美术大观,2022,(06):104-115.

11. Wang, Chong’en. “A preliminary analysis of ancient archways in Shanxi.” Shanxi Architecture, no. 24 (2004): 15–16. [in Chinese]

王崇恩. 山西古牌楼浅析[J]. 山西建筑,2004,(24):15-16.

12. Sun, Yan. “Rhetoric: The aesthetic construction of defamiliarization in literary language.” Contemporary Literary Criticism, no. 01 (2016): 21–24. [in Chinese]

孙艳. 修辞:文学语言陌生化的审美构建[J]. 当代文坛, 2016, (01): 21-24.

13. Li, Xin. “A study on traditional Chinese color culture and the development of chromatic concepts in painting.” Ethnic Arts Studies 36, no. 03 (2023): 153–160. [in Chinese]

李鑫. 中国传统色彩文化及绘画色彩观的发展研究[J]. 民族艺术研究, 2023, 36 (03): 153-160.

14. Qin, Hongling. “Architectural regulation and governance: An ethical institutional analysis of ancient Chinese architecture.” Studies in Ethics, no. 05 (2014): 27–32. [in Chinese]

秦红岭. 宫室之制与宫室之治:中国古代建筑伦理制度化探析[J]. 伦理学研究, 2014, (05): 27-32.

15. Yang, Junyi. “On the causes of transgressive decorative motifs in Jingdezhen folk kilns during the Zhengtong and Jingtai periods.” Chinese Art Studies, no. 01 (2021): 158–161. [in Chinese]

杨君谊. 正统、景泰时期景德镇民窑僭越纹饰现象出现原因探析[J]. 中国美术研究, 2021, (01): 158-161.

16. Yu, Yang. “Image narration and artistic truth: Ontological principles and key issues in contemporary Chinese thematic art creation.” Fine Arts, no. 08 (2018): 11–13, 10. [in Chinese]

于洋. 图像叙事与艺术真实——当代中国主题性美术创作的本体规律与焦点问题[J]. 美术, 2018, (08): 11-13+10.

17. Zhao, Yuyao. “A study on the intangible cultural heritage characteristics of the ‘Han Family Painted Tower’ in Pingyao.” In Proceedings of the 2020 World Human Settlements Environment Science Development Forum, 177–187. Beijing: World Human Settlements (Beijing) Institute of Environmental Science / Guojingyuan Architectural & Landscape Design Institute, 2020. [in Chinese]

赵宇耀. 平遥“韩氏彩楼”非遗艺术特征研究[A]. 世界人居(北京)环境科学研究院.2020世界人居环境科学发展论坛论文集[C].世界人居(北京)环境科学研究院:国景苑(北京)建筑景观设计研究院,2020:177-187.

18. Liu, Xiaochun, and Yixin He. “Practices of Locality: The Dynamic Formation of Hakka Seasonal Festivals in Shenzhen.” Journal of Northwestern Ethnic Studies, no. 05 (2025): 53–65. [in Chinese]

刘晓春,贺翊昕.风土的实践:深圳客家岁时节日的动态生成[J].西北民族研究,2025,(05):53-65.

19. Xiao, Li, Wei Wenqian, and Xiong Yan. “Ritual-sense furniture design based on traditional Chinese wedding rites.” Packaging Engineering 42, no. 20 (2021): 300–306. [in Chinese]

肖丽,卫文倩,熊炎. 基于中国传统婚嫁礼制的仪式感家具设计研究[J]. 包装工程,2021,42(20):300-306.

20. Han, Sumei. “Nation, ethnic space, and identity construction: A communication analysis of People’s Daily coverage of the Yushu earthquake.” Journalism & Communication Studies 18, no. 01 (2011): 51–59, 110–111. [in Chinese]

韩素梅. 国家、民族空间与认同建构:《人民日报》玉树地震传播分析[J]. 新闻与传播研究,2011,18(01):51-59+110-111.

Funding

This research is a phased outcome of the 2025 institutional research project of Tianshi College, Tianjin, “New-Quality Breakthrough: Design-Led Transformation of Local Culture and High-Quality Rural Development—Design Theory and Practice” (Project No. K25016). It is also supported as a phased outcome of the Key Theoretical Research Project of the China Arts and Crafts Society, “Design Strategies for Intangible Cultural Heritage Creative Products Driven by Artificial Intelligence: A Case Study of Pingyao Lacquerware (Tuiguangqi)” (Project No. CNACS2024-I-8).

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research.

About the Author(s)

- Yuyao Zhao is a lecturer at Tianshi College, Tianjin. His research focuses on intangible cultural heritage protection and design revitalization.

Modern narratology has moved beyond the confines of literary studies and has been widely applied across diverse forms of artistic production [2]. Rather than focusing solely on degrees and formal characteristics, contemporary narratological theory affirms the legitimacy of employing a wide range of representational strategies through which objects may be endowed with narrative qualities [3]. Aleida Assmann argues that, for images to be directly psychologized and inscribed into memory, it is necessary to select those that stimulate imagination in distinctive ways and possess a heightened capacity for mnemonic imprinting [4].

Visual narration primarily operates through two modes of temporalizing space, one of which involves the organization of images into sequences, thereby reconstructing an imagistic flow of events [5]. This theoretical framework provides a basis for treating handicraft practices as valid objects of narratological inquiry.

With social transformation, many traditional folk customs rooted in agrarian societies have diverged significantly from contemporary modes of life and have gradually disappeared. The continued high frequency of Jin-style painted festival towers in the Shanxi region, however, indicates the remarkable vitality of this form of folk art and its associated technical system. From its initial emergence through its ongoing evolution, the narrative characteristics of Jin-style painted festival towers have yet to be fully explored. Investigating these features not only enables a departure from conventional perspectives in fine arts or design studies but also offers an alternative approach to understanding the contemporary cultural value of folk art [6].

Such structural simplification does not signify a loss of meaning; rather, it establishes the necessary narrative space in which symbolic, decorative, and ritual functions can supersede utilitarian concerns. By stripping away material permanence and functional redundancy, Jin-style painted festival towers transform architectural form into a flexible narrative scaffold, enabling the amplification of festive spectacle and collective imagination.

3.2. Decorative Alienation as Narrative Accentuation in Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

As with traditional pailou architecture, roof ornamentation constitutes a principal decorative component in Jin-style painted festival towers, jointly shaping the majority of their visual appearance. In Jin-style painted festival towers, the central ridge point and terminal ends of the roof are typically adorned with colorful zoomorphic figures, embroidered balls, vegetal motifs, or geometric forms created through the niucai (twisting and binding) technique. These elements function as abstract substitutes for conventional pailou components such as chiwen ridge ornaments and finials (宝顶), translating architectural symbolism into a distinctly handcrafted idiom (Figure 10).

By contrast, traditional pailou architecture commonly incorporates dougong bracket sets, which serve both structural load-bearing and ornamental functions. In Jin-style painted festival towers, however, the dougong is subjected to a process of decorative alienation: it is transformed into an upward-curving, planar structure woven through niucai techniques, retaining only a symbolic resemblance to its architectural prototype. Influenced by the limits and inheritances of craft transmission and material conditions, Jin-style painted festival towers often present a deliberate ambiguity between structure and ornament when compared with pailou architecture.

Unlike the fixed and standardized construction logic of pailou architecture, the decorative motifs of Jin-style painted festival towers do not adhere to rigid replication of architectural components at corresponding positions. Moreover, these substituted elements no longer perform any actual structural or load-bearing function. Through the interweaving of multiple narrative languages, certain structural forms and components of Jin-style painted festival towers are rendered estranged from their original architectural roles, becoming ornamental accents that operate beyond structural necessity.

This process of decorative alienation enables ornamentation to detach from architectural subordination and assume narrative primacy. As a result, decorative elements no longer merely embellish structure but function as expressive nodes within a broader ritual and symbolic system, reinforcing the tower’s transformation from architectural reference into festive spectacle.

3.3. Color Binarization as the Narrative Tonal Foundation of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

As the formal source of Jin-style painted festival towers, traditional Chinese architecture follows a chromatic system whose logic differs markedly from that of Jin-style painted festival towers, resulting in two distinct modes of visual expression. In the Zhou dynasty, five colors—cyan (青), red, yellow, white, and black—were established as orthodox colors. Palaces, columns, walls, and platforms were predominantly painted red. By the Yuan dynasty, architectural color schemes had become increasingly diversified, with decorative polychromy incorporating red, yellow, blue, and green. During the Qing dynasty, chromatic hierarchies were further systematized and rigidly codified: yellow-glazed tiles occupied the highest rank, followed by blue, purple, black, and green, producing an increasingly opulent and stratified visual order.

In contrast, the chromatic logic of Jin-style painted festival towers, shaped through the interweaving of multiple narrative languages, manifests a distinctly binarized system of color use. Within Han Chinese cultural traditions, color carries multilayered symbolic meanings that reflect both elevated spiritual aspirations and deeply embedded folk customs. Jin-style painted festival towers typically operate through two dominant chromatic binaries: red–yellow for auspicious celebrations and black–white for funerary contexts, each encoding sharply differentiated symbolic values.

Jin-style painted festival towers erected for weddings employ a red–yellow palette as their primary chromatic scheme. Horizontal couplet inscriptions often feature auspicious phrases such as Zhulian Bihe (珠联璧合, a perfect union), accompanied by decorative painting motifs imbued with symbolic blessings. Red lanterns further reinforce the festive atmosphere, establishing an overall tonal register of joy and prosperity (Figure 11). By contrast, towers constructed for funerary rites predominantly adopt a black–white color scheme, supplemented by restrained accents of yellow or blue. In such contexts, horizontal inscriptions commonly read Jia He Xi You (驾鹤西游, riding a crane westward), while beam elements are decorated with predominantly white painted motifs. White lanterns marked with the character Dian (奠, mourning) are displayed, flanked by ritual tables and paired crane figures, collectively establishing a solemn and reverential tonal field (Figure 12).

Conclusion

Narrative, as one of the earliest forms of human record-making, conveys stories and ideas through expressive structures. While folk art and traditional handicrafts have been widely discussed in terms of their contemporary design value, the question remains: can they themselves be considered “design”? From the perspective of a broad conception of design studies, traditional handicrafts may be understood as forms of “ancient design.” This reframing provides a theoretical foundation for translating folk art into the discourse of design. The more pressing issue, however, lies in how such practices can reciprocally inform contemporary design.

With the emergence of visual narrative and its integration into design practice, narrative themes, plots, contexts, and visual expressions have increasingly become objects of systematic design innovation. In this sense, the narrative process itself becomes the design process. Approaching folk art as ancient design through the lens of narratology thus offers a robust framework through which traditional practices may meaningfully nourish contemporary design.

In summary, the narrative language of Jin-style painted festival towers can be classified into four categories: formal imitation, material substitution, technical substitution, and functional substitution. Correspondingly, their narrative artistic principles unfold across four dimensions: first, structural simplification, which establishes the formal foundation of narrative articulation; second, decorative alienation, which generates points of visual emphasis; third, chromatic dualism, which defines the narrative tone; and fourth, visual transgression, which delineates the value orientation of the narrative. Building upon these principles, Jin-style painted festival towers negotiate the relationship between the collective and the individual and reconcile historical specificity with artistic individuality—issues of enduring relevance for contemporary design practice.

Most crucially, however, the narrative action embodied in Jin-style painted festival towers actively facilitates the formation of ritual itself. Viewed from this perspective, such visible and experiential forms of narrative are widely present within Chinese folk material culture. It is precisely this capacity to be seen, felt, and collectively experienced that constitutes the practical significance of folk art for contemporary design.

4. Narrative Imagery Characteristics of Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

Narrative art fundamentally confronts two core issues: first, how to negotiate the relationship between the collective and the individual; and second, how to reconcile the characteristics of a given historical moment with artistic individuality [16]. The narrative imagery of Jin-style painted festival towers does not correspond to any specific location, historical period, or concrete architectural prototype. Rather, it may refer to any one of the numerous traditional buildings or archways found throughout Shanxi Province, or function as a highly abstract artistic symbol distilled from regional architectural forms.

Most Jin-style painted festival towers share a gateway-like structure, typically consisting of a central opening framed by vertical supports, above which are beam-like elements. These are often surmounted by plaques or a secondary tier resembling a pavilion and further capped by roof forms analogous to hip-and-gable or gable roofs [17]. In their early stages, these structures were constructed from wooden poles or bamboo, bound using lashing techniques and wrapped in red paper or fabric. In later periods, iron frameworks became more common; some continued to employ traditional binding techniques, while others adopted modular fastening systems. Covering materials likewise evolved, ranging from painted textiles to the continued use of earlier materials out of craft tradition. On the columns of the gateway structure, neatly arranged couplets are affixed, using written language to articulate layered emotional and symbolic meanings associated with the festival or ritual occasion.

These Jin-style painted festival towers are typically erected along central streets by artisans and, over the course of historical development, have been recognized and legitimated by society—namely by local residents, patrons, and commissioning bodies—thereby acquiring multiple layers of meaning.

On the one hand, Jin-style painted festival towers function as devices for intensifying the atmosphere of ritual time. Their temporariness generates a heightened sense of ceremony, introducing elements that distinguish ritual moments from everyday life. In regions such as Pingyao, the construction of Jin-style painted festival towers constitutes an indispensable component of rituals associated with the Spring Festival, weddings, and funerals. The erection of red-toned towers defines the ritual time as celebratory, while towers dominated by black-and-white color schemes guide the ritual toward a somber and mournful register.

Secondly, the form of Jin-style painted festival towers operates as a comprehensive visual symbol derived from traditional archway architecture. It reflects the artisan’s capacity to grasp the shared formal essence of architectural imagery—isolating key features and materializing them in simplified form. As demonstrated in the preceding analysis and the visual examples (Figure 1), these structures correspond closely to the architectural imagery held collectively by both artisans and the wider public. Through this convergence, specific formal characteristics resonate with shared cultural memory, generating a sense of familiarity and affective proximity.

On another level, Jin-style painted festival towers extend both the temporal duration and spatial reach of festive activities, functioning as a prelude and an epilogue to the festival itself. By means of ritualization, the towers separate ritual time from everyday life, making visible the opposition between the extraordinary and the ordinary. From the moment of their construction, they detach participants and spectators from their habitual modes of existence [18]. This function is comparable to that of a university entrance examination countdown clock—not in signaling the precise number of days remaining, but in initiating an anticipatory state long in advance. Similarly, Jin-style painted festival towers prolong the mnemonic span of festivals, preparing the emotional ground ahead of time and fostering collective anticipation during a period of symbolic “countdown.”

Finally, the narrative imagery of Jin-style painted festival towers fulfills collective expectations regarding the theme of forthcoming festivals, while simultaneously enabling the anticipation of pleasurable experiences and the projection of a satisfying continuation of present life. As these structures gradually appear in public spaces and accumulate in number as the festival approaches, public interest intensifies. This cumulative process amplifies the emotional impact of the festival itself, psychologically priming participants and enhancing the density of ritual experience. In this way, Jin-style painted festival towers serve as narrative catalysts that heighten affective investment and deepen the sense of ceremonial immersion.

5. Ritual as Narrative Action: Jin-style Painted Festival Towers

Ritual may be understood as a patterned form of behavior—a voluntary mode of action that generates symbolic effects or enables participants to engage sincerely with lived experience [19]. The construction of Jin-style painted festival towers constitutes a form of narrative action endowed with ritual significance. On the one hand, it functions as a materialized symbol of popular belief and as a tangible embodiment of folk ritual itself. On the other hand, during ritual time, it operates as a handcrafted object that imitates real architectural archways through multiple forms of substitution. Its distinctive techniques and material strategies demonstrate a high level of craftsmanship characteristic of vernacular artisanal traditions.

At the same time, Jin-style painted festival towers can be regarded as a necessary narrative action within ritual time and as one of the key mechanisms through which a sense of ritual is produced. Benedict Anderson has argued that through ritualized modes of mediated reception, individuals acquire shared cultural experiences and an awareness of other social members who partake in the same experiences, thereby forming an “imagined community” [20]. Jin-style painted festival towers function precisely as such a medium. Their presence enables ritual times—such as the Spring Festival in certain regions of Shanxi—to achieve consistency in both meaning and form, corresponding to the continuity and durability of local folk customs. Without the sustained repetition of this narrative action, the symbolic content of ritual time would risk becoming diffuse and indeterminate.

In the creation of Jin-style painted festival towers, ritual itself emerges through narrative action. The combined operation of multiple narrative languages produces specific psychological cues for the collective, transmitting deeper conceptions of life and festive meaning. This narrative action realizes a dialectical unity between the imitated object and the object of imitation, generating visual contradictions and the resulting sense of tension and impact. Through formal imitation, the substitution of materials and techniques, and the transformation of function, artisans ultimately move beyond purely technical reproduction and enter the domain of ritual performance.