A Moving Landscape: West Lake in Hangzhou as a Pictorial Theme and its Representation on Export Lacquer Screens

by Zhenji He 1 * , Ya Ye

1 China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2025, 3(2), 26-43; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2025.1019a13

Received: July 28, 2025 | Accepted: September 25, 2025 | Published: October 19, 2025

Introduction

Located in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, the West Lake has always been renowned for its beautiful and pleasant scenery. It is said that the West Lake in Hangzhou was also called “Wulin Water” (武林水), “Jinniu Lake” (金牛湖), “Mingsheng Lake” (明圣湖) and “Qiantang Lake” (钱塘湖) during the Han Dynasty. In the Tang and Song Dynasties, the West Lake was known as “Shihan Lake” (石函湖), “Gaoshi Lake” (高士湖), “Xizi Lake” (西子湖) and similar names. So far, the name “West Lake” (西湖) has been especially popular among all the names. The earliest records of the name of “the West Lake” can be found in the poems of Bai Juyi, namely Looking Back at the Lonely Hill on My Way across West Lake (西湖晚归回望孤山寺赠诸客) and Sailing Homewards (杭州回舫). In the Song Dynasty, Su Shi first used the name “West Lake” in an official document, namely Memorial from Hangzhou Requesting Monastic Certificates [in Order to] Dredge the West Lake (杭州乞度牒开西湖状) [1].

From then on, numerous literati of dynasties have highly praised the scenery of the West Lake and expressed it through literature. The West Lake gradually became a cultural symbol representing Chinese traditional culture. As a sought-after and persistently revisited creative theme, The West Lake’s cultural influence and artistic value were continuously expanded and strengthened in later generations. It was disseminated to foreign regions through international exchanges, becoming an important carrier for the early overseas image of China.

3. The Artistic Dissemination of the West Lake Landscape

The naming of the “Ten Scenes of the West Lake” in Hangzhou and the use of these views as the themes for artistic expression can be traced back to Ma Yuan of the Southern Song Dynasty. But the tradition of “writing descriptions of scenic spots” (题写名胜) in China emerged much earlier. The technique of expressing emotions through landscape has a long history in Chinese classical literature, having been popular as early as the pre-Qin period. With the prevalence of Tang poetry, it became fashionable to combine scenery with poetry in the Tang Dynasty. There was a trend towards integration between scenery, poetry and painting. In the Song Dynasty, the combination of landscape and poetry gradually became popular.

Before the rise of the “Ten Scenes of the West Lake” in the Southern Song period, the landscape painting phenomenon known as the “Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang” (潇湘八景) had already emerged during the Northern Song period. In the “Calligraphy and Painting” (书画) section of his Dream Pool Essays (梦溪笔谈), Shen Kuo (沈括) stated that Song Di (宋迪), the Vice Director in the Ministry of Revenue, was a skilled painter, especially proficient in depicting level-distance landscapes. His most accomplished works included Wild Geese Descending on a Sandbank (平沙雁落), Returning Sails from a Distant Shore (远浦归帆), Mist-Laden Village on a Market Day (山市晴岚), Evening Snow over River and Sky (江天暮雪), Autumn Moon over Dongting Lake (洞庭秋月), Night Rain on the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (潇湘夜雨), Evening Bell from a Mist-Shrouded Temple (烟寺晚钟), and Evening Glow over a Fishing Village (渔村落照). These scenes were called the “Eight Scenes” and were widely circulated by connoisseurs [6].

According to this document, the Northern Song Dynasty painter Song Di preceded other connoisseurs in the pioneering act of inscribing titles for scenic views and using them as his artistic subject matter. Song Di [courtesy name Fugu (复古)] was from Luoyang (洛阳), Henan (河南) Province and lived approximately from the eighth year of the Dazhongxiangfu (大中祥符) era to the fifth year of the Yuanfeng (元丰) era (1015-1082 CE) of the Northern Song Dynasty. He once served as Vice Transportation Commissioner of the Jinghu (荆湖) South Circuit. He was familiar with the geography and landscape of the Xiang River (湘江) Basin, so he had long been using the beautiful scenery of the mountains and waters in that region as his creative subject matters. Song Di’s contributions to form the “Eight Scenes of Xiaoxiang” theme and create the related paintings were highly praised by the celebrated calligrapher and painter Mi Fu (米芾) of that time, who even wrote poems and prefaces for the paintings. Since then, the name of “Eight Scenes” has been prevalent.

The origin of “Eight Scenes” (八景) and its prevalence in later generations are profoundly connected to the ancient people’s understanding of “eight.” The phenomenon of dividing related things into eight categories and using “eight” as the general term has been widely spread and accepted. This is evident in concepts like the “Eight Trigrams” (八卦), “Eight Directions” (八方), and “Eight Avenues” (八达), all of which are explicitly linked to notions of direction and space. The origin of the term “Eight Scenes” can be traced back to the Daoist concept of “Scenes of the Eight Temporal Nodes” (八方之景), which later expanded to the spatial concept of “Scenes of the Eight Directions” (八时之景) [7]. The cultural phenomenon of the “Eight Scenes” became particularly popular after the Song Dynasty. Cultural landscapes like the “Eight Scenes of Yanjing (燕京) [the old name of Beijing(北京)]”, “Eight Scenes of Luoyang (洛阳),” and “Eight Scenes of Yangcheng (羊城) [the old name of Guangzhou (广州)]” not only appear extensively in ancient Chinese local gazetteers, but are also directly represented through poetry and illustrations within these texts.

Simultaneously, the “Eight Scenes” gradually evolved into a generic term and a paradigm used to group together a cluster of scenic spots in a particular location. Those scenic spots would be collectively named as the “Eight Scenes.” Besides the “Eight Scenes,” there are also some designations like “Ten Scenes”, “Sixteen Scenes,” “Twenty-Four Scenes,” and even “Seventy-Two Scenes.” As previously mentioned, “Ten Scenes of West Lake,” “Eighteen Scenes of West Lake,” and “Twenty-Four Scenes of West Lake” are all prime examples of this naming convention. Although “Eight Scenes” is the most widely used designation, the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” is more famous. Following the emergence of the titles for the “Ten Scenes of West Lake,” corresponding paintings also began to appear.

In addition to the works of Ma Yuan, artist Chen Qingbo (陈清波) drew paintings such as Three Pools Mirroring the Moon (三潭印月图), Spring Dawn on the Su Causeway (苏堤春晓图), Lingering Snow on the Broken Bridge (断桥残雪图), Lotus Flowers in the Breezing Winding Courtyard (曲院风荷图), Evening Bell Ringing at Nanping Hill (南屏晚钟图), and Leifeng Pagoda in the Evening Glow (雷峰夕照图). Painter Liu Songnian also created the Four Views of West Lake (西湖四景图). In the late Southern Song Dynasty, there appeared albums like Ma Lin (马麟)’s Album of the Ten Scenes of West Lake (西湖十景册) and Ye Xiaoyan (叶肖岩)’s Album of the Ten Scenic Views of West Lake (西湖十景图册). By this time, the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” had become a relatively complete and fixed subject matter for painting.

From the late Ming Dynasty into the Qing Dynasty, paintings of the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” flourished once again. The works of the Ming period included Qi Min (齐民)’s Album of the Ten Views of West Lake (西湖十景图册), Lan Ying (蓝瑛)’s Ten Scenes of West Lake (西湖十景图), Song Maojin (宋懋晋)’s Scenic Sites of West Lake (西湖胜迹图), and Bian Wenyu (卞文瑜)’s Album of the West Lake (西子眉册). In the Qing Dynasty, notable examples were Wang Yuanqi (王原祁)’s Ten Views of West Lake (西湖十景图), Dong Bangda (董邦达)’s Scroll of the Ten Views of West Lake (西湖十景图卷), Liu Du (刘度)’s Ten Scenes of West Lake (西湖十景图), Dong Gao (董诰)’s Ten Scenes of West Lake (西湖十景图), Lyu Huancheng (吕焕成)’s Album of West Lake Landscapes (西湖山水册), and Zhang Ruoai (张若霭)’s Panoramic View of West Lake (西湖全景图). These works demonstrated the superb representational skills of Ming and Qing painters in depicting the West Lake scenery and the brilliance of different artistic styles.

From the Ming Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty, particularly during the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong(乾隆) eras, the cultural landscape of the West Lake in Hangzhou was meticulously renovated and artistic creations depicting its scenery reached their zenith. Among them, the production of woodblock prints on West Lake themes developed rapidly. Notable examples in the Ming Dynasty included Newly Inscribed Marvels Within the Seas containing the West Lake images, the color-printed album Hushan Shenggai (湖山胜概) [The Splendors of Lakes and Hills] integrating poetry, calligraphy, and painting, as well as the Topical Compendium of the Gazetteer of West Lake (西湖志类钞). In the Qing Dynasty, the multi-color print Stories of the West Lake (西湖佳话) were produced during the reign of Emperor Kangxi.

During the Qianlong period, the officially compiled Illustrated Record of the Southern Inspection Tours (南巡盛典) and the re-compiled Edited Gazetteer of West Lake (西湖志纂) all contained engraved images of the West Lake. Rongguang Hall (容光堂) also carved the Imperial Complete Map of West Lake: Renowned and Newly Designated Scenic Sites (御览西湖胜景新増美景全图) in the Guangxu (光绪) period. Regardless of their intended use as travelogue maps, ceremonial records, novel illustrations, or for other purposes, the popularity of these West Lake-themed woodblock prints contributed to the dissemination and reinforcement of the influence of the West Lake cultural landscape through their circulation [8]. Furthermore, the scenery of West Lake, as a subject for artistic creation, was not only popular in the printmaking of the Ming and Qing dynasties, but also served as a vital subject matter for other forms of art.

Since the Southern Song Dynasty, the depiction of the West Lake’s scenery—whether through its canonical sets like the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” or through a individual scene or several scenes—has become a very distinctive creative theme in the history of Chinese landscape painting. After the Ming Dynasty, the depictions of the scenery of West Lake had expanded beyond the realm of ink-wash landscape paintings and reached other forms of artistic expression. Printmaking was one of the important mediums among them. At the same time, the cultural landscape construction of the West Lake in the Ming Dynasty also entered a stage of restoration and reconstruction. For instance, in the third year of Zhengde (正德) era (1508 CE), the Prefect Yang Mengying (杨孟瑛) carried out a large-scale dredging of the West Lake. He used the silt excavated to raise the Su Causeway, and constructed a long embankment parallel to the Su Causeway in Xili Lake(西里湖) and six bridges. Those renovations improved and expanded the tourist area. In the 39th year of Wanli(万历) reign (1611 CE), Yang Wanli constructed a circular long embankment from south to west outside the release pond on the Xiaoyingzhou (a small island in the West Lake). This construction project formed a unique landscape of “an island in the lake and a lake within the island” (湖中岛, 岛中湖) [9]. In the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties, the beautiful and charming scenery of West Lake had gained worldwide fame. The dissemination of related prints, illustrations and literary works like poetry and novels, played a significant role in promoting this reputation.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- 1. The Renovation History of the West Lake in Hangzhou

- 2. The Formation of the “Ten Scenes of West Lake”

- 3. The Artistic Dissemination of the West Lake Landscape

- 4. The Scenery of West Lake Depicted on the Lacquer Screen

- Conclusion

- Author Contribution

- Funding

- Acknowledgments

- Conflicts of Interest

- About the Author(s)

- References and Notes

1. The Renovation History of the West Lake in Hangzhou

In later generations, the West Lake in Hangzhou was transformed into a prominent creative theme favored by Chinese art. This situation was due to its unique natural geographical conditions and the continuous literary and artistic creations regarding it since the Tang Dynasty. The term “West Lake” derives from its geographical location to the west of the historic center of Hangzhou. In the past, the West Lake was a lagoon formed at the estuary of the Qiantang River. With years of sediment accumulation, this lake became a closed and isolated water area. As a freshwater lagoon, the water quality of the West Lake is excellent. Thus, the lake is regarded by the common people of Hangzhou as the source of their domestic water. Before the middle and late Tang Dynasty, the West Lake had not undergone large-scale development and remained in its natural formation encompassed by mountains and waters.

In the middle Tang Dynasty, especially with the outbreak of the An Lushan(安禄山) Rebellion (755-763 CE), the Tang Empire entered a period of decline from prosperity. At that time, not only did the Tang Empire’s national strength decline during the rebellion, but its population also sharply decreased. Meanwhile, people in the north kept moving southward to escape the wars. As the economic center, the Jiangnan(江南) region attracted a large number of people to settle. During this particular period, Hangzhou was favored by a substantial number of cultured and virtuous people. After moving southward, they played an important role in the construction and development of the region. Since then, a series of large-scale renovations were carried out on the West Lake in Hangzhou, which laid a crucial foundation for establishing its cultural landscape features.

Although the renovations of the West Lake after the middle and late Tang Dynasty were an important foundation forming its cultural landscape, the original purpose of these renovations was actually to meet the water needs of the people in Hangzhou. Due to its proximity to the sea, Hangzhou usually experienced seawater intrusion. Affected by the sea tide, the domestic water became salty and undrinkable. In the second year of the Jianzhong (建中) era (781 CE) of the Tang Dynasty, Li Bi (李泌) arrived in Hangzhou as Provincial Governor. To solve the water shortage problem faced by the people of Hangzhou, he organized the construction of six wells that connected to the West Lake, including West Well (西井), Square Well (方井), Golden Bull Pool (金牛池), White Turtle Pool (白龟池), Little Square Well (小方井), and Xiangguo Well (相国井). This renovation project used bamboo pipes and an underground conduit to channel the water from the West Lake into the city and form a water storage system. This system closely linked the West Lake and the development of Hangzhou. Later, in the second year of the Changqing (长庆) era (822 CE) of the Tang Dynasty, Bai Juyi (白居易) assumed the post of the Governor of Hangzhou. He noticed that the six old wells built by Li Bi in the city were in a dilapidated and neglected state. So he directed the cleaning and dredging of the six wells to facilitate the water supply for the people of Hangzhou. At the same time, Bai Juyi undertook a project to rehabilitate the West Lake, which had been clogged by aquatic plants and silt for a long time. He oversaw the construction of the dam to ensure a sufficient water supply for the lake, which would be beneficial for irrigation. As late as the Northern Song Dynasty, the main purpose of the renovations to the West Lake was still to store water and alleviate the damage caused by drought.

The so-called “Ten Scenes” is an important subject matter for poets and painters. They created literary or artistic works around the natural scenery or the man-made attractions of the West Lake. In the late Southern Song Dynasty, there were more and more famous poems and lyrics with the theme of “Ten Scenes of West Lake.” Paintings depicting the landscapes of the south also became prevalent, but the creations related to the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” were not very mature.

After the fall of the Song Dynasty, the Imperial Hanlin Painting Academy no longer existed. The related artistic creations, as well as the maintenance of the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” after the Yuan Dynasty, fell into a period of decline. It was not until the Ming Dynasty that they began to recover and develop again. For instance, the Xiaoyingzhou (小瀛洲) [a small island in the West Lake] of “Three Pools Mirroring the Moon” was planned and constructed. Similarly, the large bell of Jingci Temple (净慈寺), which was referred to in “Evening Bell Ringing at the Nanping Hill” (南屏晚钟), was rebuilt.

In the Qing Dynasty, the West Lake was developed on a relatively large scale, and the cultural traditions of the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” was successfully revived and promoted once again. During the reign of the Kangxi (康熙) Emperor (1661-1722 CE), the emperor undertook six Southern Tours and personally inscribed the “Ten Scenes of West Lake.” Based on his calligraphic works, local officials subsequently erected stone tablets. Later, during the reign of the Yongzheng (雍正) Emperor (1723-1735 CE), Li Wei (李卫), the Governor-General of Zhejiang (浙江) at the time, presided over a large-scale construction project of West Lake landscapes. This project led to the expansion of the scenic list, forming the “Eighteen Scenes of West Lake,” namely Spring Shrine of Lake Hill (湖山春社), Arch of Merit and Virtue (功德崇坊), Jade Belt Rainbow in Clear Sky (玉带晴虹), Evening Glow at Xishuang Pavilion (海霞西爽), Cranes Returning to Plum Grove (梅林归鹤), Autumn Lotuses in Fish Pond (鱼沼秋蓉), Pine Lodge by Lotus Pool (莲池松舍), Phoenix Pavilion on Precious Stone Hill (宝石凤亭), Horseback Archery at the Pavilion Bay (亭湾骑射), Music Played by Banana-Shaped Rocks (蕉石鸣琴), Fish Leaping at Jade Spring (玉泉鱼跃), Wind through Pines on Phoenix Ridge (凤岭松涛), Level View from Lake Center (湖心平眺), Grand View from Wu Hill (吴山大观), Incense Market at Tianzhu Temple (天竺香市), Bamboo-lined Path at Yunqi (云栖梵径), Viewing the Sea from Taoguang Temple (涛光观海), and Seeking Plum Blossoms at Xixi Wetland (西溪探梅).

During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1735-1796 CE), the Qianlong emperor also made six southern tours to Hangzhou. While visiting the West Lake, he frequently composed poems and inscribed for the scenery. For instance, he inscribed the “Twenty-Four Scenes of the West Lake,” which included Spring Shrine of Lake Hill (湖山春社), Phoenix Pavilion on Precious Stone Hill (宝石凤亭), Jade Belt Rainbow in Clear Sky (玉带晴虹), Grand View from Wu Hill (吴山大观), Cranes Returning to Plum Grove (梅林归鹤), Level View from the Lake Center (湖心平眺), Music Played by Banana-Shaped Rocks (蕉石鸣琴), Fish Leaping at Jade Spring (玉泉鱼跃), Wind through Pines on Phoenix Ridge (凤岭松涛), Incense Market at Tianzhu Temple (天竺香市), Viewing the Sea from Taoguang Temple (韬光观海), Bamboo-lined Path at Yunqi (云栖梵径), Seeking Plum Blossoms at Xixi Wetland (西溪探梅), Garden of a Small Paradise (小有天园), Lakeside Pavilion in the Rippling Garden (漪园湖亭), Mountain Lodge of Lingering Harmony (留余山居), Bamboo-Clad Rolling Hills (篁岭卷阿), Villa of Chanting Fragrance (吟香别业), Ancient Cave of Auspicious Rock Hill (瑞石古洞), Yellow Dragon Cave Dressed in Green (黄龙积翠), Universal View from the Incense Terrace (香台普观), Terrace of Clear Contemplation (澄观台), Six Harmonies Pagoda (六和塔), and Hall of Narrating Antiquity (述古堂) [5]. Nevertheless, Qianlong's own poems on the subject revealed that the “Ten Scenes of the West Lake,” a designation dating back to the Southern Song period, still held the highest place in his esteem.

2. The Formation of the “Ten Scenes of West Lake”

Since the middle and late Tang Dynasty, with a large number of scholars and officials migrating to the south, literary creations related to the West Lake in Hangzhou also increased substantially. The renowned poet Bai Juyi mentioned earlier wrote many popular poems about the West Lake, such as The Lake in Spring (春题湖上) and Farewell to the West Lake (西湖留别). The poets who composed poems with the theme of West Lake also included Liu Changqing (刘长卿), Xue Neng (薛能), Zhang Hu (张祜), Qi Ji (齐己), Li Shen (李绅), Du Fu (杜甫), etc. In addition, the works of local poets such as Lin Bu (林逋) and Wu Rong (吴融) bore witness to the changes in society from the late Tang Dynasty to the end of the Tang Dynasty. By the time of the Song Dynasty, the famous poet Su Shi, as mentioned earlier, had produced his works Drinking on the Lake, First in Sunshine and Then in Rain (饮湖上初晴后雨) (I & II), which were spread widely and praised in later generations. Moreover, Yang Wanli (杨万里)’s work Seeing a Friend off at Dawn from Jingci Monastery (晓出净慈寺送林子方) was also highly popular and spread widely.

Apart from the poetic works inspired by the “poetic charm” (诗情) of the West Lake, the artworks depicting the “picturesque beauty” (画意) of West Lake also rapidly developed. After entering the Southern Song Dynasty, those artworks achieved an unprecedented level of prosperity. The concept of “Ten Scenes of West Lake” (西湖十景) emerged, which was rooted in natural scenery and blended with the artistic essence of landscape. This concept subsequently served as a paradigmatic model for shaping the cultural landscape of Hangzhou’s West Lake.

As a labeled landscape, the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” in Hangzhou have had a wide reputation since the Song Dynasty. The early representative record of the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” was in Fangyu Shenglan (方舆胜览) [A Comprehensive Geography Book of Song Dynasty], a book completed around the third year of Jiaxi (嘉熙) era of Emperor Lizong (理宗) of the Southern Song (1239 CE). It was written by Zhu Mu (祝穆), a native of Jianyang (建阳). As Zhu Mu stated in Fangyu Shenglan, (the West Lake) was located in the west of Hangzhou, with a circumference of thirty miles. Its water source came from numerous streams and springs in the surrounding valleys. The mountain scenery was charming and graceful. Throughout the year, elegant boats were cruising on the lake, and the sounds of singing and music could be heard continuously day and night. Some enthusiasts of the West Lake had nominated ten scenes, namely: Autumn Moon over the Calm Lake (平湖秋月), Spring Dawn on the Su Causeway (苏堤春晓), Lingering Snow on the Broken Bridge (断桥残雪), Leifeng Pagoda in Evening Glow (雷峰落照), Evening Bell Ringing at the Nanping Hill (南屏晚钟), Lotus Flowers in the Breezing Winding Courtyard (曲院风荷), Viewing Fish at Flower Harbor (花港观鱼), Listening to Orioles Singing in the Willows (柳浪闻莺), Three Pools Mirroring the Moon (三潭印月), and Twin Peaks Piercing the Clouds (两峰插云) [3]. The above is the earliest known record of the “Ten Scenes of West Lake” so far. It is said that the “busybody” (好事者) who proposed to name scenic spots in the West Lake after the “Ten Scenes” might be the renowned painter Ma Yuan (马远) at that time [4].

Ma Yuan [courtesy name Yaofu (遥父), art name Qinshan (钦山)] hailed from Hezhong (河中) [present-day Yongji (永济)], but was born in Qiantang (钱塘) [present-day Hangzhou]. His family had been serving as court painters for generations. After the “Jingkang Incident” (靖康之变), his family moved south to Qiantang. He was active in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, specifically from the era of Emperor Guangzong (光宗) to that of Emperor Ningzong (宁宗) (1189-1224 CE) of the Southern Song Dynasty. Ma Yuan inherited the family tradition of painting and was skilled in depicting themes like figures, landscapes, flowers, and birds. His landscape paintings were particularly outstanding, and he was able to come up with original ideas. When designing the composition of landscape paintings, Ma Yuan skillfully utilized the blank spaces at the edges to express the aesthetic atmosphere of emptiness and remoteness. This style earned him the title of “One-Corner Ma” (马一角) in the history of Chinese painting. Ma Yuan stood out among the painters of the Imperial Hanlin (翰林) Painting Academy during the Southern Song Dynasty. He was ranked alongside his fellow Academy painters Li Tang (李唐), Liu Songnian (刘松年), and Xia Gui (夏圭) as one of the “Four Great Masters of the Southern Song Dynasty” (南宋四家). Their works represented the highest artistic level of Chinese landscape painting during the Southern Song period.

4. The Scenery of West Lake Depicted on the Lacquer Screen

The deep affection for the scenery of West Lake led to the widespread application of its related artistic themes, particularly the poetic and pictorial “Ten Scenes of West Lake,” into the real-life environment. This phenomenon can be seen in various architectural projects, interior decoration, and furniture ornamentation. Among them, the most notable one was the construction of Qing Dynasty imperial gardens drawing inspiration from the West Lake scenery. This practice further promoted the development of the illustrated poetry tradition, fostering a deeper integration of gardens and literature within the art of painting.

Furthermore, by the Ming and Qing dynasties, the scenery of West Lake became a decorative theme symbolizing refined taste. It was increasingly incorporated into the design of various objects used in daily life. The most representative extension of this trend was its application in furniture decoration. This was especially evident in the design of objects like screens, which had large decorative surfaces and allowed for the incorporation of materials. The traditional Chinese architecture primarily employed a post-and-beam structural system, so the spatial layout particularly relied on the use of furniture like screens and partitions.

Meanwhile, China has a long and rich tradition of painting screens. The “painting screen” (画屏) refers to the use of paintings to decorate screen furniture. These decorative paintings are made of various materials. The later popular format of vertical panel paintings is related to the use of screens. Apart from screens whose core is a painting directly made on paper or silk, productions that depict decorative themes through lacquer techniques are both magnificent and durable. Therefore, the lacquer is highly popular among the artistic media used for screen making. The origins of lacquer screens could be traced back to remote antiquity, but screens specifically decorated with landscape paintings or scenery paintings did not appear until the Six Dynasties and the Tang Dynasty. After the Song Dynasty, driven by the prosperity of landscape painting, the production of lacquer screens achieved significant development. The ancient paintings passed down now confirmed that landscape-themed screens were prevalent in the Song Dynasty. It is unfortunate that no specific physical remains of such lacquer work have been found so far.

During the Ming Dynasty, it became fashionable to use lacquer technique to decorate screens with various themes. the Tianshui Ice Mountain Records (天水冰山录) listed a total of 389 screens, including White Stone Plain Lacquer Screen, Qiyang (祁阳) Stone Screen, Painted Screen with Japanese Gold Embellishments, Folding Screen with Multi-color Lacquer, Black Lacquer Folding Screen with Gold Leaf Application, Fording Screen with Butterflies (painted lacquer with Japanese gold embellishments), Fording Screen with Floral Pattern (painted lacquer with Japanese gold embellishments), Fording Screen with Three Friends of Winter (gold-paste lacquer), Fording Screen with Landscape (gold-paste lacquer) and similar works [10].

The prosperity of lacquer screen production in the Ming Dynasty was connected to the comprehensive maturation of lacquer decoration techniques. As mentioned earlier, landscape painting themes, represented by the “Ten Scenes of West Lake,” were extremely prevalent at that time. This situation naturally led to these images become decorative themes for lacquer painting screens. Especially from the late Ming to early Qing periods, printed images of West Lake scenery were in vogue. Lacquer screens decorated with West Lake themes by using the kuancai (款彩) [incised polychrome] technique became classic designs of such works and were highly favored. The term kuancai is described in the lacquer technique classic Xiushilu (髹饰录) [Records of Lacquering] of the Ming Dynasty. Under the “Engraving and Carving - Tenth” chapter, its production is noted to have versions using “lacquer colors” (漆色) and others using “oil colors” (油色). The former are suitable for dry filling, while the latter are suitable for paste backing. There were also versions incorporating gold and silver as decoration, resulting in a greatly gorgeous effect. Moreover, there were monochrome productions and lacquer wares purely made with intermixed gold and silver.

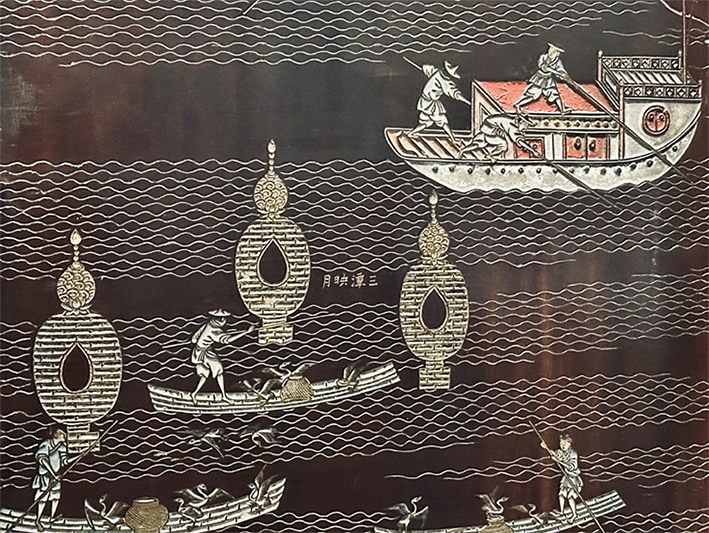

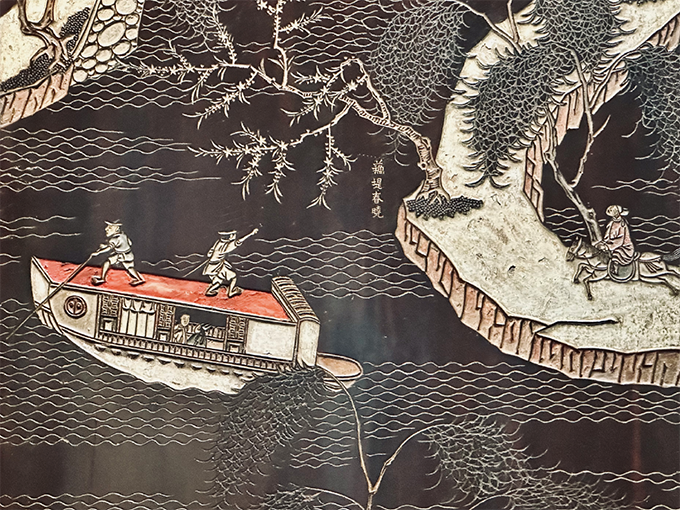

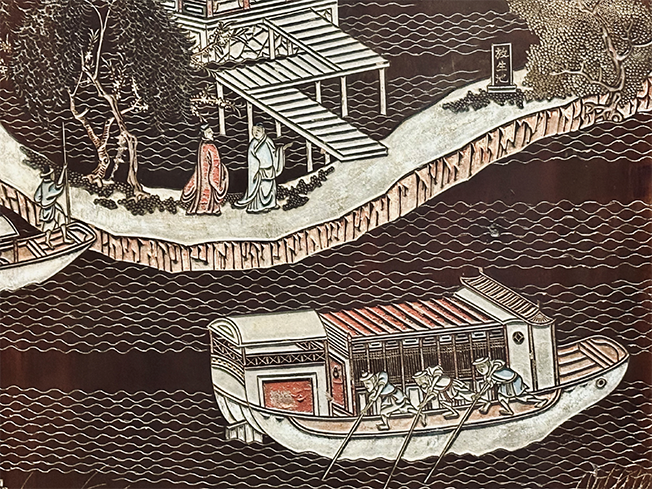

“Kuancai” is characterized by its unique production process. The technique creates a printing plate-like effect by carving pre-designed patterns into the lacquer surface, a process known as “kuan” (款). Then, colors are filled in the recessed areas. It is from this defining two-step process of “kuan (incising)” and “cai (coloring)” that the technique derives its name. However, monochrome productions are not called kuancai, but are named, according to the single color used, as “kuan (incised)-[color]” [11]. The carving process and artistic effect of kuancai technique are very similar to those of printmaking. Therefore, taking the popular printed images of West Lake scenery as design inspiration for kuancai lacquer screens is a natural choice. More importantly, the consumers of such lacquer screens were often the social elite, gentry, or wealthy literati, whose artistic tastes frequently held a special fondness for cultural landscapes like the “Ten Scenes of West Lake.” This situation made screens adorned with this kind of themes greatly beloved. Coupled with the exquisite craftsmanship of lacquer techniques, they further became elegant and luxurious gifts (Figures 1-8).

Abstract

Based on its unique natural scenery and the later humanistic shaping, the West Lake in Hangzhou gradually became one of the most popular themes in traditional Chinese culture and art since the Tang and Song Dynasties. Through the form of “Ten Scenes of West Lake,” it was transformed into an artistic carrier that integrated poetry, landscape and painting. After the Song Dynasty, the artistic theme of the West Lake increasingly broke through the traditional scholarly-oriented paradigm of classical landscape painting, and moved into the increasingly popular field of decorative arts. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, this theme was assimilated into the construction of gardens as well as the decoration of furniture and daily objects through various designs and techniques. From the creation of landscape paintings to the production of woodblock print illustrations, and then to the development of lacquer screen decoration designs, the artistic expression of the scenery of the West Lake reflected the persistent spiritual pursuit of the Chinese people. They looked for an artistic life that integrated nature and human culture. Meanwhile, as the spread of Chinese export art in the Ming and Qing dynasties continued, the landscape of the West Lake in Hangzhou, as a regional landmark, became a popular subject for paintings and decorations. With this trend, this theme gradually spread to regions outside East Asia. Lacquered screens depicting the scenery of the West Lake and other movable artworks played a significant role in this process. With their circulation, the beauty of the West Lake was transmitted to all corners of the world.

Edited by: Eloise

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Zhenji He, and Ya Ye, "A Moving Landscape: West Lake in Hangzhou as a Pictorial Theme and its Representation on Export Lacquer Screenss." JACAC 3, no.2 (2025): 26-43.

AMA Style

He ZJ, Ye Y. A Moving Landscape: West Lake in Hangzhou as a Pictorial Theme and its Representation on Export Lacquer Screens. JACAC. 2025; 3(2): 26-43.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References and Notes

1. [Song Dynasty] Shi, Su. Complete Works of Sushi. Beijing: Yanshan Publishing House, 2009, 2014–2016.

[宋] 苏轼:《苏东坡全集》,北京:燕山出版社,2009年,第2014-2016页。

2. [Song Dynasty] Mi, Zhou. Old Stories of the Capital City Hangzhou. Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House, 2011, 81.

[宋] 周密:《武林旧事》,杭州:浙江古籍出版社,2011年,第81页。

3. [Song Dynasty] Mu, Zhu. A Comprehensive Geography Book of Song Dynasty. Beijing: Zhonghua Books Publishing House, 2003, 7.

[宋] 祝穆:《方舆胜览》,北京:中华书局,2003年,第7页。

4. Chen, Ye. Four Great Masters of the Southern Song Dynasty. Beijing: Research Publishing House, 2024, 187–188.

陈野 等:《南宋四家》,北京:研究出版社,2024年,第187-188页。

5. Wu, Jing. West Lake’s Poetry. Hangzhou: Hangzhou Publishing House, 2005, 209.

吴晶:《西湖诗词》,杭州:杭州出版社,2005年,第209页。

6. [Song Dynasty] Kou, Shen. Dream Pool Essays. Xi’an: Sanqin Publishing House, 2008, 94.

[宋] 沈括:《梦溪笔谈》,西安:三秦出版社,2008年,第94页。

7. Yue, Lisong. The Cultural Writing of Scenic Gardens in the Qing Dynasty. Xi’an: Shanxi Normal University Press, 2024, 11–12.

岳立松:《清代园林集景的文化书写》,西安:陕西师范大学出版社,2024年,第11-12页。

8. Pan, Zhiliang. Ancient Print of West Lake. Hangzhou: Hangzhou Publishing House, 2020, 31.

潘志良:《西湖古版画》,杭州:杭州出版社,2020年,第31页。

9. Zhejiang Provincial Construction Industry Annals Compilation Committee, ed. Zhejiang Building Industry Chronicle. Beijing: Local Chronicle Publishing House, 2004, 886.

浙江省建筑业志编纂委员会 编:《浙江省建筑业志》,北京:方志出版社,2004年,第886页。

10. He, Zhenji. Chinese Ancient Lacquer Ware. Hangzhou: China Academy of Art Press, 2020, 190.

何振纪:《中国古代漆器》,杭州:中国美术学院出版社,2020年,第190页。

11. [Ming Dynasty] Huang, Cheng, and Ming. Yang Xiushilu (Records of Lacquering). Beijing: China Renmin University Press, 2004, 55.

[明]黄成 著、杨明 注:《髹饰录》,北京:中国人民大学出版社,2004年,第55页。

Author Contribution

Zhenji He conceived the topic and structure of the article and wrote the introduction, conclusion, and Sections 1 and 4. Ya Ye wrote Sections 2 and 3.

Funding

This article was supported by the Ministry of Education of China through the Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Project No. 24YJA760037).

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge the financial support from the Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education of China and the assistance of Yingru Wu with terminology translation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Author Biographies

- Zhenji He is a Professor at the China Academy of Art.

Ya Ye holds a Master’s degree in Chinese Painting from the China Academy of Art and is currently a professional artist specializing in Chinese painting.

In this period, the most representative figure who participated in the renovations of the West Lake was Su Si (苏轼). Su Shi served in Hangzhou twice in his lifetime. The first time was in the fourth year of Xining (熙宁) era of Emperor Shenzong (神宗) of the Song dynasty (1071 CE), when he served as Tongpan (通判) [a supervisory official ranked just below the prefect] of Hangzhou. The second time was in the fourth year of Yuanyou(元祐) era of Emperor Zhezong of Song (1089 CE), when he assumed the post of the Governor of Hangzhou. Su Shi spent five years in Hangzhou. When Su Shi first arrived in Hangzhou, he noticed that the sedimentation problem in the West Lake was serious. In the year following his second appointment to serve in Hangzhou (1090 CE), he submitted a memorial titled Memorial from Hangzhou Requesting Monastic Certificates [in order to] Dredge the West Lake to the imperial court. He earnestly requested the imperial court to grant Hangzhou one hundred monastic certificates to fund the dredging of the West Lake. Su Shi pointed out the significance of managing the West Lake in multiple aspects, such as the water supply for the common people, agricultural irrigation, the smoothness of waterways, and the facilitation of water transportation. After receiving support from the imperial court, Su Shi promptly took action. He led the dredging of the Maoshan river (矛山河) and the Yanqiao river (盐桥河), as well as the restoration of six wells. He also used the large amount of silt dug up to build a long embankment in the west part of the lake, connecting the north and the south.

Later, in order to commemorate Bai Juyi’s contribution to the construction of the lake embankment, Hangzhou renamed Baisha Causeway as Bai Causeway, while the long embankment built by Su Shi was called Su Causeway. These renovation projects maintained the essence of deriving wealth from the city and serving the people. Although the original purpose of building these lake embankments was for lake water utilization, those lake embankments, on the basis of the natural landscape of the mountains and waters, contributed to forming the initial ecological landscape features of the West Lake gardens. For instance, when Su Shi was building the Su Causeway, he planted peach trees and willows all along it, creating a scene of pink peach blossoms and green willows. This became the prototype of the famous West Lake scenic spot “Spring Dawn on the Su Causeway” (苏堤春晓). Furthermore, Su Shi erected three small stone pagodas facing each other in the deep pool in the middle of West Lake. Those pagodas became the initial outline of the “Three Pools Mirroring the Moon” (三潭印月) scenic spot in later times.

After becoming part of the Southern Song Dynasty, Linan (临安) [the old name for Hangzhou] became the capital. Because of the continuous growth of population and the rapid development of the economy, Hangzhou became the most prosperous place at that time. With the prosperous social economy, the West Lake in Hangzhou gradually became the focus of urban life and artistic creation. Its specific appearance increasingly showed a trend of being more recreational and scenic. In the late Song and early Yuan period, Zhou Mi(周密), a native of Wuxing(吴兴) [the old name of Huzhou(湖州)], recorded the scenes of people visiting the West Lake in his book Wulin Jiushi (武林旧事) [Old Stories of the Capital City Hangzhou]. During this period, the West Lake was a public space where people of Linan could have fun, celebrate festivals, enjoy music and singing, and participate in Buddhist rituals. Literary and artistic creations related to the West Lake have also been continuously emerging and evolved towards thematic narratives. It formed a distinctive artistic style characterized by lyrical and symbolic qualities. This situation created favorable conditions for the formation of the West Lake cultural landscape and the dissemination of the West Lake as a cultural symbol [2].

A typical example of a kuancai lacquer screen can be found in a Kangxi period “Kuancai Lacquer Screen with a Panoramic View of West Lake” (款彩西湖全景图漆屏风), housed in the Hangzhou West Lake Museum (杭州西湖博物馆). This screen, with a black lacquer ground throughout, consists of twelve panels joined together to form a complete panoramic image of West Lake. The panoramic view is surrounded by a border composed of the Eight Buddhist Emblems. The entire image is grand in scale, with various figures dotting the mountain and water scenery of the lake. It is rich in detail and features bright, cheerful colors. The reverse side is plain lacquer. Inscriptions on the screen indicate that it was a birthday gift commissioned by Wang Chaojun (王朝俊), Commissioner-in-chief of the Left Battalion of the Central Army in the Nan'ao (南澳) Brigade of Qing Dynasty, and other military officers from the the Nan’ao Brigade. The gift was specially made for the elderly Mr. Zhou (周老先生), who was then overseeing the entire Fujian (福建) naval forces. The congratulatory message was composed by Chen Tianda (陈天达).

Additionally, the Tiantai Museum (天台博物馆) in Zhejiang Province houses another “Twelve-Panel Kuancai Lacquer Screen with a Panoramic View of West Lake” (款彩西湖全景图十二扇漆屏风) of the Qing Dynasty. The decorative image on this screen is very close in artistic style to the one in the Hangzhou West Lake Museum. This screen was commissioned during the Kangxi period by officials from Ouning (瓯宁) County for Shi Zhijie (施之杰), an official from Tiantai. Shi Zhijie brought this precious gift back to his hometown Tiantai after retiring from his post. The screen is comprised of twelve panels, with a black lacquer ground. It depicts the scenic beauty and bustling life around Hangzhou’s West Lake through delicate and skilled kuancai technique. The image is surrounded by a border decorated with patterns of flowers, plants, and auspicious animals. The reverse side bears the birthday congratulatory text, composed by Zheng Kaiji (郑开极).

Beyond these two examples, similar kuancai lacquer screens using the West Lake theme can also be found among the Chinese lacquer screens cherished by Gabrielle Bonheur Chanel, the founder of Chanel. Kuancai lacquer screens were widely popular in the early Qing Dynasty and became sought-after bestsellers among Chinese export artworks. These screens provided charming decorations and design inspirations for the emerging European “Chinoiserie” style.

Conclusion

The westward transmission of Chinese kuancai lacquer screens began as early as the Ming Dynasty. After being introduced to Europe, these screens were named “Coromandel” screens. The term “Coromandel” originally referred to a region on the southeastern coast of India. As this area served as a transit hub for East-West trade at that time, it concentrated together various goods from China, including kuancai lacquer screens. This situation led to the name becoming a synonym for Chinese kuancai lacquer wares. This kind of screen was highly popular among European customers, because it could be folded to save shipping space and costs. More importantly, screens had a range of uses. After arriving at their destination, they could be modified into decorative panels according to the requirements of the collectors and then installed in furniture and interior decorations.

Relevant artifacts confirmed that lacquer screens, painting the scenery of the West Lake with colorful lacquer and gold lacquer, were extremely prevalent in the late Qing Dynasty. A typical representative example is a magnificent twelve-panel “Large Birthday Screen with West Lake Landscape (embossment lacquer with gold paint),” now housed in the Guangdong Museum. It can trace back to the Daoguang (道光) period (1821-1850 CE) of the Qing Dynasty. Its exquisite craftsmanship and splendid style make it a classic work of this category. In addition to the lacquer screens, the West Lake theme is also frequently presented in the decorative designs of other collectibles and luxury items, such as brocades and embroidery, ceramics, glassware, and even ink sticks. After entering the 20th century, international exchange and communication in the field of Chinese art has continuously expanded. With this expansion, the West Lake in Hangzhou, embodying the refined taste of Jiangnan culture within traditional Chinese art, has been transformed into a spiritual symbol and cultural icon. The West Lake, as a cultural symbol, continues to play a significant role in various cultural and artistic mediums up to the present day.