Edited by: Eloise

Forms and Functions of Dining Utensils in Northern Song Tomb Murals: Archaeological Insights

by Yuanjun Cui , Hong He *

China Academy of Art, Hangzhou, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2025, 3(2), 1-25; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jacac2025.0930a12

Received: June 19, 2025 | Accepted: August 25, 2025 | Published: September 30, 2025

Introduction

The Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE) marked a cultural zenith in Chinese history, characterized by a policy of prioritizing civil governance over military affairs, which elevated scholar-officials’ roles in political and cultural spheres. This environment fostered a sophisticated humanistic culture, emphasizing elegance and aesthetic refinement in everyday material culture, particularly dining utensils. Northern Song tomb murals, especially those from archaeological sites in Henan and Hebei provinces, vividly capture the prominence of banqueting culture, documenting social practices and offering critical insights into the forms, functions, and arrangements of dining utensils. These murals, executed on brick or stone, serve as a dynamic visual medium, preserving banquet scenes through artistic expression and providing reliable evidence for studying Song Dynasty dining practices. Integrated with archaeological discoveries, such as ceramics from Ding, Cizhou, and Jun kilns, and textual records from contemporary sources, the murals reveal the morphology, usage contexts, and ritual significance of utensils like wine warmers, warming bowls, cups, and storage vessels. These artifacts reflect not only practical adaptations—such as enhanced insulation for warming wine—but also social hierarchies, ritual conventions, and aesthetic ideals that defined Northern Song society.

This study explores how these utensils, as depicted in tomb murals, illuminate the interplay of functionality and symbolism in banquet culture, offering a lens into the social, cultural, and artistic dynamics of the period. By synthesizing visual, material, and textual evidence, this research aims to deepen understanding of Northern Song dining practices, contribute to the study of Song material culture, and establish a methodological framework for interpreting historical imagery in archaeological contexts.

3. Compositional Forms and Cultural Characteristics of Dining Utensils in Northern Song Tomb Murals

A large number of research samples provide a chronological framework for analyzing dining utensils in banquet scenes, revealing distinct patterns in their compositional distribution, usage frequency, and material types. Based on the identification of dining utensils in banquet scenes, their compositional patterns can be divided into three main categories. These patterns take the basic configuration of “two saucer-cups and one wine ewer” as a foundation, with variations in the types and quantities of utensils.

3.1. Compositional Forms

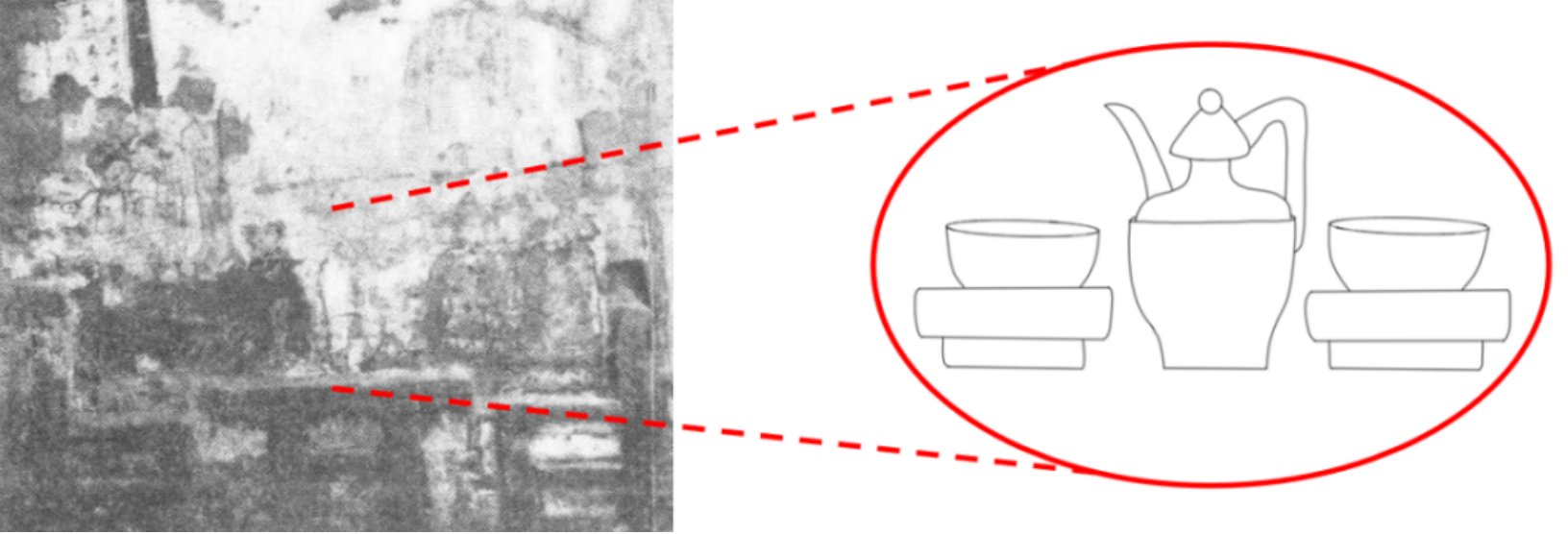

3.1.1. “One Ewer, Two Cups” Basic Configuration

The first category represents the simplest and most fundamental compositional style, featuring two saucer-cups placed on either side of the table, with a wine ewer positioned at the center. Examples include the Kaifang Banquet Scene on the eastern wall of the Song Dynasty mural tomb in Gucun, Xin’an County, Henan (Figure 8), and the banquet scene on the eastern wall of the Shecun tomb in Gongyi, Henan. In some tomb mural depictions of seated couples, the wine ewer is not placed between the two drinking utensils on the table but is instead held by an attendant. Nevertheless, the overall configuration of “one ewer, two cups” is maintained. Examples include the couple’s banquet scene on the northwest wall of the Song Dynasty mural tomb in Heishangou, Dengfeng, Henan (Figure 9), and the couple’s banquet scene on the western wall of Tomb M13 in Huaixi, Xingyang, Henan.

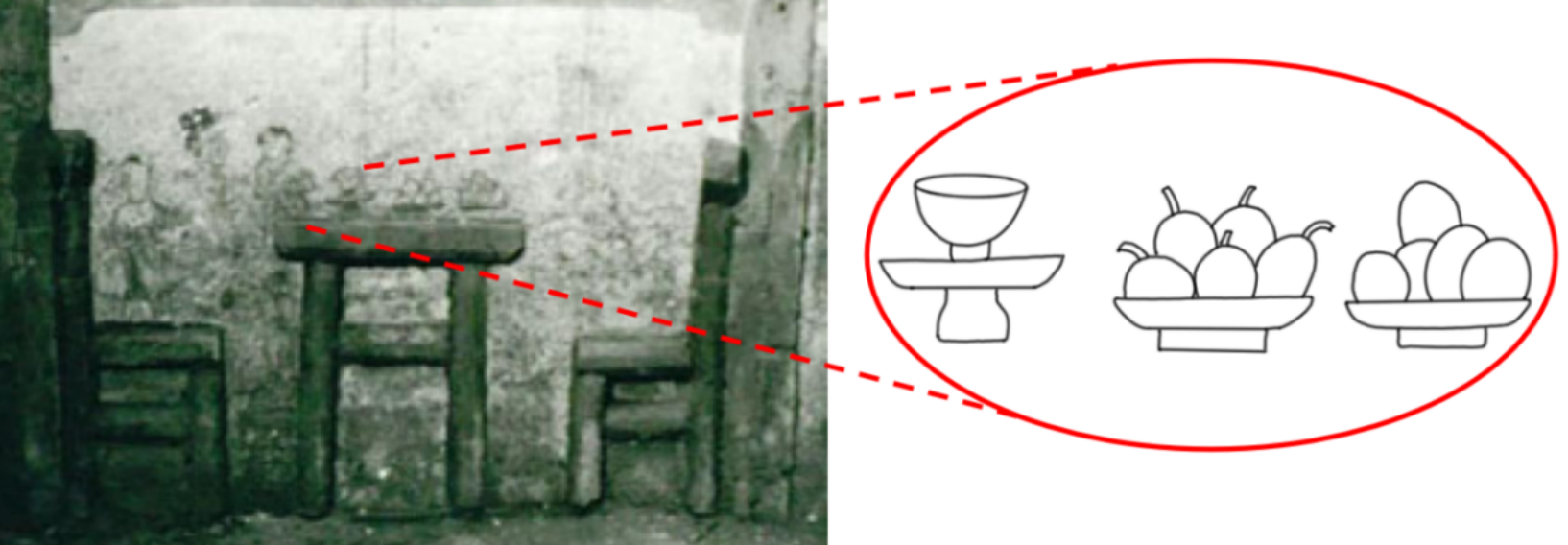

3.1.3. Irregular Configuration

The third category lacks a clear pattern and occasionally features discrepancies between the number of tomb occupants depicted and the sets of dining utensils present. For instance, in the couple’s banquet scene on the southwest wall of Song Tomb No. 2 in Baisha, Yu County, Henan, no saucer-cup is placed on the table near the female figure. Similarly, in the banquet scene on the western wall of the Northern Song dated mural tomb in Guxian, Hebi, Henan [9], only one of the two chairs is occupied by a figure (Figure 12). On the left side of the table, an elderly woman with a high chignon sits in a chair, accompanied by a male and a female child, while the right side of the table remains unoccupied. The table holds one set of saucer-cups and two plates of fruit.

5. Cultural Significance

5.1. Entertainment-Oriented Banqueting Activities

Private banqueting in the Song Dynasty flourished alongside the growth of the commodity economy and urban prosperity. Tea houses, wine shops, and eateries proliferated in the streets and alleys, offering sophisticated banqueting services. Additionally, during festivals, birthdays, or social visits, households with better financial means often prepared “family banquets,” and an industry specializing in catering such events began to emerge and develop. Banqueting activities in the Northern Song were closely intertwined with the arts, frequently incorporating music, dance, and poetry during gatherings. In tomb murals, banquet scenes are often accompanied by depictions of musical and dance performances, emphasizing the joy of family life and the pursuit of pleasure and entertainment. For example, the decorative layouts of tombs such as the Song Dynasty brick-carved tomb in Wangjia Xinyao, Tianshui City, Gansu, and the Song tombs in Heishangou, Dengfeng, Baisha Tomb No. 1, and Xiaonanhai, Anyang, Henan, feature both banqueting and musical performance themes, illustrating scenes where performances enhance the festive atmosphere of banquets.

5.2. A Domesticated Afterlife

Banqueting activities in the Northern Song Dynasty were not only frequent but also held significant importance in daily life. Song Dynasty Neo-Confucianism (lixue) promoted ethical and moral values centered on family and clan relationships, advocating for rational, restrained, and harmonious living principles and social order. The Kaifang Banquet, a specific type of banquet shared between couples (or lovers), emerged under the influence of Neo-Confucian thought as a key expression of familial happiness and marital affection. Scenes of seated couples are prevalent in Northern Song tomb murals. In Baisha Song Tombs, Mr. Su Bai notes that the couple’s image in Tomb No. 1 closely resembles descriptions of the Kaifang Banquet found in ancient texts, leading him to name the scene accordingly. This naming convention for Kaifang Banquet has since been adopted to specifically refer to couples’ banquet scenes in Song and Yuan tomb decorations.

The tomb structures, designed to mimic domestic layouts, and the mural content, depicting scenes of daily life, reflect an inseparable connection between the construction of the afterlife and real-world existence. These depictions embody a funerary belief that views tombs as reflections of worldly life and idealized portrayals of an aspirational existence. Consequently, the scenes portrayed in tombs represent moments considered significant and blissful in life, underscoring the prevalence and importance of banqueting activities in the Northern Song period.

5.3. Specialized Division of Labor in Dining

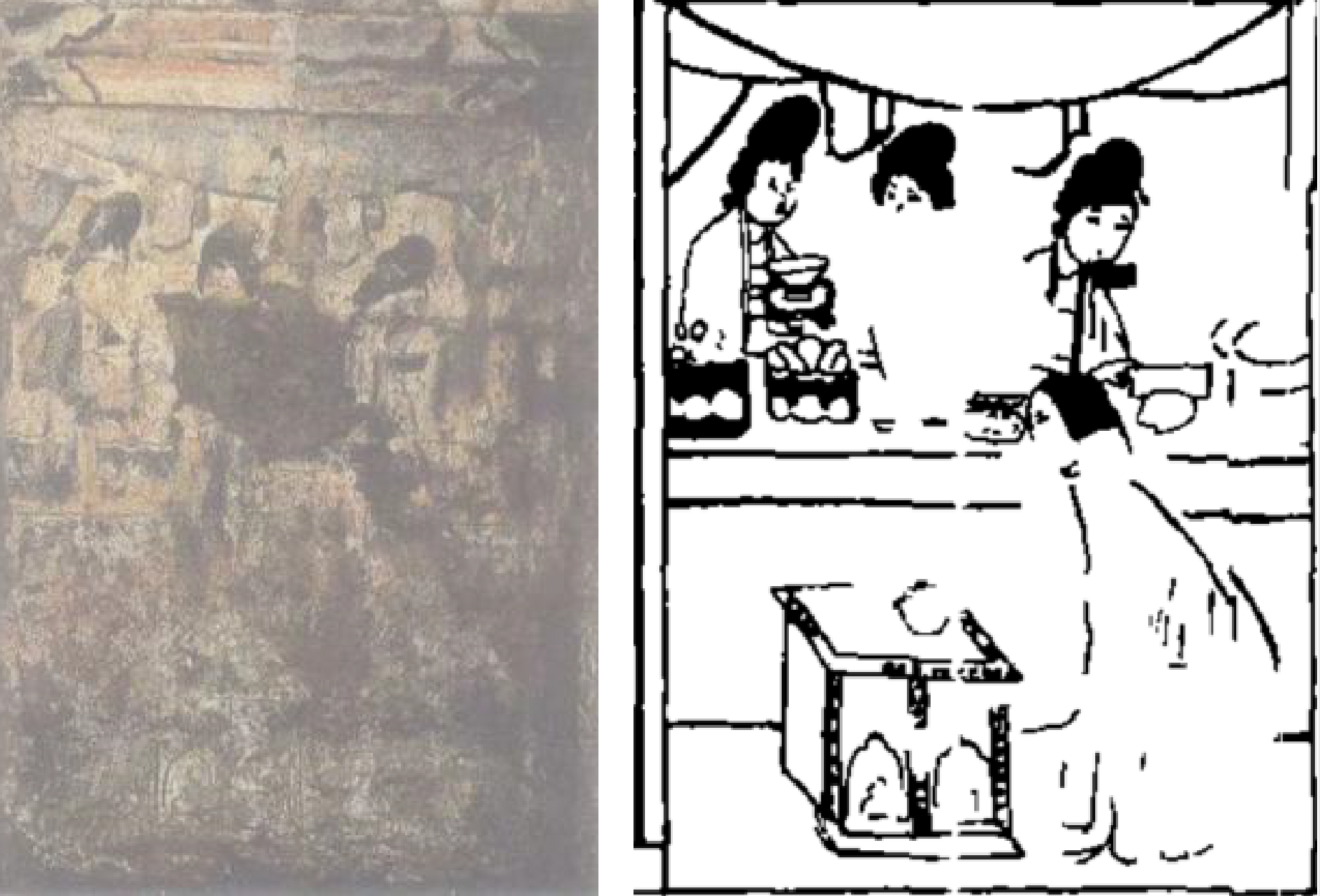

The Song Dynasty’s emphasis on agriculture and the introduction of high-yield crop varieties enhanced the professionalism and refinement of dining culture. This is first evident in the detailed personnel arrangements for banqueting activities. Based on the analysis of Northern Song banquet scenes, each stage of the banquet process was assigned dedicated personnel. For example, the banquet preparation scene on the eastern wall of the Song Dynasty mural tomb in Pingmo, Xinmi City, Henan [17], depicts four female attendants preparing food and drink (Figure 15).

2.2. Drinking Utensils

Drinking utensils, such as tea and wine vessels, often appear alongside eating utensils in banquet scenes. Tea was used to facilitate refined conversation, while wine served to express emotions and foster conviviality. Drinking utensils, designed for holding and consuming liquids, primarily include cups with saucers, wine ewers with bowls, and slender-necked bottles.

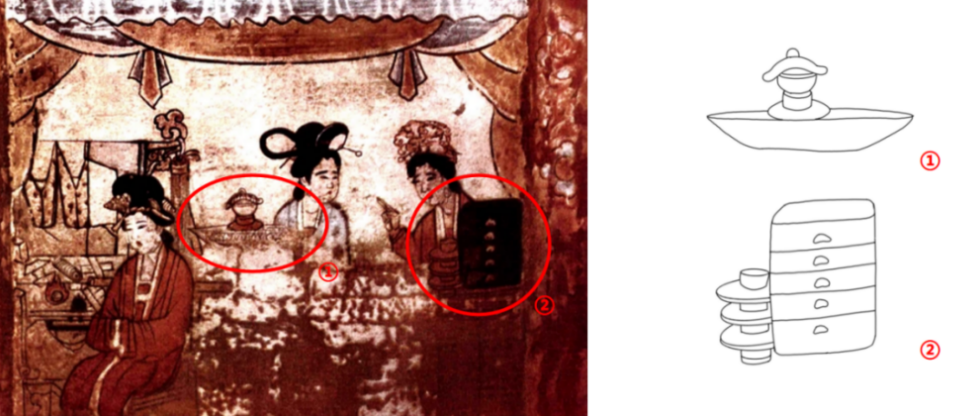

2.2.1. Cups and Saucers

Among all dining utensil types, cups with saucers (referred to here as saucer-cups) appear most frequently. The term “saucer-cups” denotes the paired use of a cup and its saucer. In addition to ceramic saucers, lacquered saucers, described as “lacquered carved dense cabinets” in the Southern Song scholar Shen’an Laoren’s Illustrated Praise of Tea Utensils (茶具图赞) [4], were highly popular in the Song Dynasty due to their excellent heat insulation. In tomb murals, some saucers are depicted in dark colors, likely indicating lacquered materials. For example, in the tea-serving scene on the southeast wall of Song Tomb No. 2 in Baisha, Yu County, Henan [5], a female attendant at the center holds a patterned tray with both hands in a tea-serving gesture (Figure 3). On the tray is a saucer-cup set, with the cup being white and topped with a lotus-leaf-shaped lid. The accompanying saucer is vermilion. On the right side of the mural, a small tea table holds a rectangular drawer-like cabinet, beside which a stack of vermilion saucers is placed. In the couple’s banquet scene on the southwest wall of the same tomb, a light-colored teacup paired with a vermilion saucer reappears. The mural’s well-preserved condition allows identification of the saucer’s fluted rim, resembling the style of a mid-Northern Song vermilion lacquered saucer excavated from a tomb in Beihuan New Village, Changzhou, Jiangsu (Figure 4) [6].

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- 1. Dining Utensils in Northern Song Dynasty Tomb Murals

- 2. Common Types of Dining Utensils in Northern Song Tomb Murals

- 3. Compositional Forms and Cultural Characteristics of Dining Utensils in Northern Song Tomb Murals

- 4. Analysis of the Forms of Daily Dining Utensils Depicted in Northern Song Tomb Murals

- 5. Cultural Significance

- Conclusion

- Author Contribution

- Funding

- Acknowledgments

- Conflicts of Interest

- Author Biographies

- References and Notes

2.2.3. Slender-Necked Bottles

In addition, banquet scenes in tomb murals feature vessels in the form of bottles or jars, which are commonly identified in excavation reports as wine storage containers. A notable example is the tall black bottle depicted on the western wall of Song Tomb No. 1 in Baisha. In his book Baisha Song Tombs, Mr. Su Bai provides a detailed analysis, noting an inscription on the headscarf of the figure holding the bottle that reads “Cui Dalang’s Wine.” Based on this, he argues that the vessel is a wine container. Drawing on excavated materials and literature from other regions, Su Bai further posits that such bottles are meiping (plum vases) and were referred to as jingping (capital bottles) during the Song Dynasty. This view, that meiping were known as jingping in the Song period, has become a mainstream perspective in discussions about the origin of meiping. Jingping, matching this description, appears in several Northern Song tomb murals (Figure 7), characterized by a small mouth, slanted shoulders, deep body, and flat base, with some featuring leaf or cord patterns on the shoulder and body. These bottles are typically placed under tables or held by female attendants.

1. Dining Utensils in Northern Song Dynasty Tomb Murals

The Northern Song Dynasty marked a pinnacle in Chinese tomb decoration, advancing the traditions of earlier dynasties. Fueled by economic prosperity, this era enabled even commoners to commission tombs adorned with intricate murals, particularly in regions like Henan and Hebei. Shaped by secular lifestyles and the funerary concept of “treating the dead as the living” (事死如事生), these tombs mirrored the architectural layouts of contemporary residences and featured vivid domestic scenes. These murals serve as both historical records and idealized depictions of societal aspirations, reflecting the ritual systems, social customs, and aesthetic values of Northern Song society.

Banqueting is a central theme in these tomb murals, necessitating a clear definition of “banquet scenes.” Narrowly, banquet scenes portray figures actively engaged in dining or drinking. However, archaeological reports employ varied terms—such as “seated couple images” (夫妇对坐图), “tea preparation scenes” (备茶图), “banquet preparation scenes” (备宴图), “drinking scenes” (对饮图), “tomb occupant lifestyle images” (墓主人生活图像) reflecting inconsistent nomenclature across sites like Kaifeng and Baisha. For this study, which examines dining utensils, a broader definition is adopted, encompassing any mural imagery depicting daily banqueting activities (excluding sacrificial rituals) and identifiable utensils in Northern Song life. This approach facilitates a comprehensive analysis of utensils like wine warmers (zhu), warming bowls (zhuwan), saucer-cups (zhan), and plates, which reveal the interplay of functionality and ritual symbolism. By integrating mural evidence with archaeological finds from kilns such as Ding and Cizhou, and textual records, this study illuminates utensil morphology, usage contexts, and their role in reflecting social hierarchies and cultural practices, offering a window into the refined banqueting culture of the Northern Song Dynasty.

Cups are typically used in conjunction with saucers, but occasionally appear alone or stacked in some mural images. For instance, in the banquet preparation scene on the eastern wall of a Song Dynasty mural tomb in Nanwuli Village, Laizhou, Shandong [7], inverted teacups are stacked beside a tea basket in the upper right corner, alongside saucers, plates, and dishes, ready for use. This arrangement allows the thin porcelain cup walls to fit closely together, saving space, while the inverted position keeps the cup rims downward, facilitating cleanliness and easy handling [8].

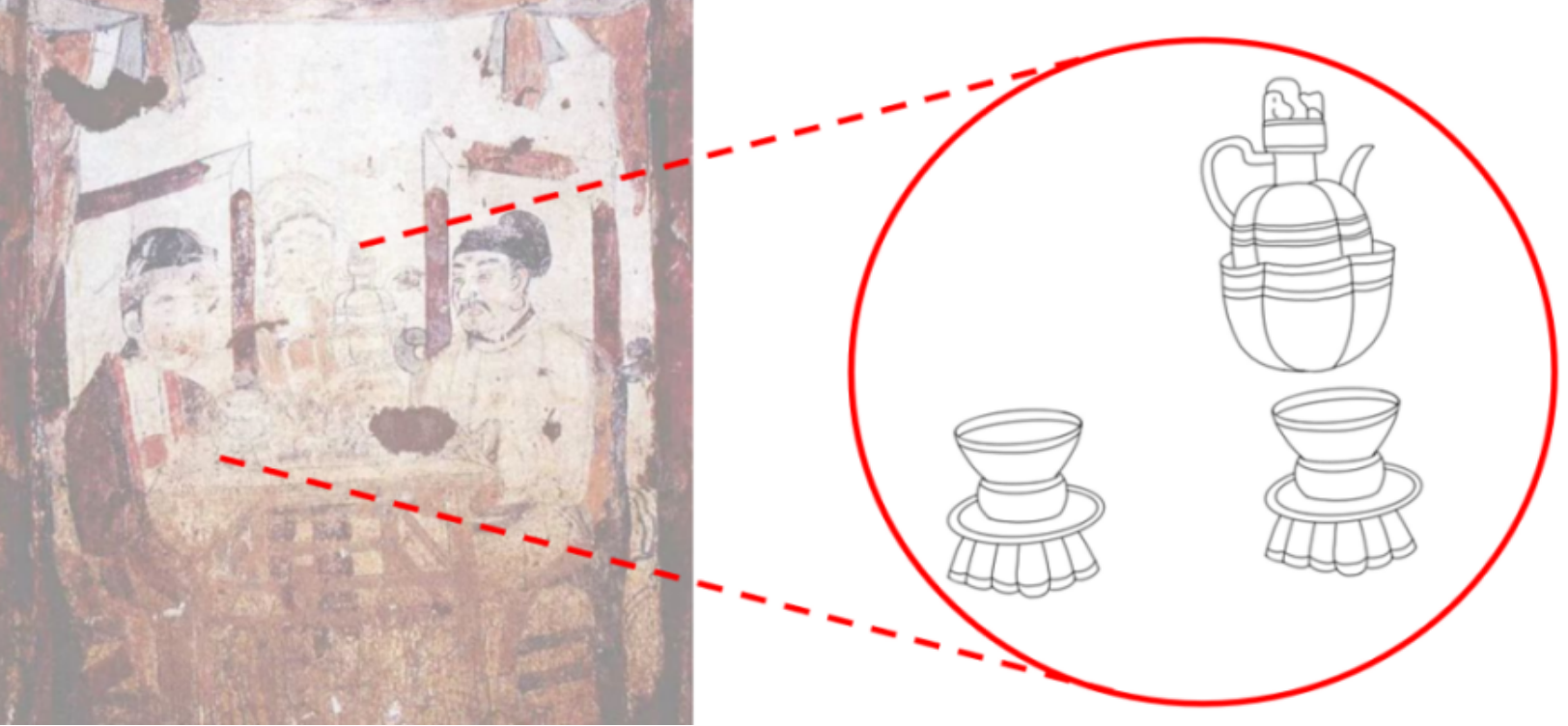

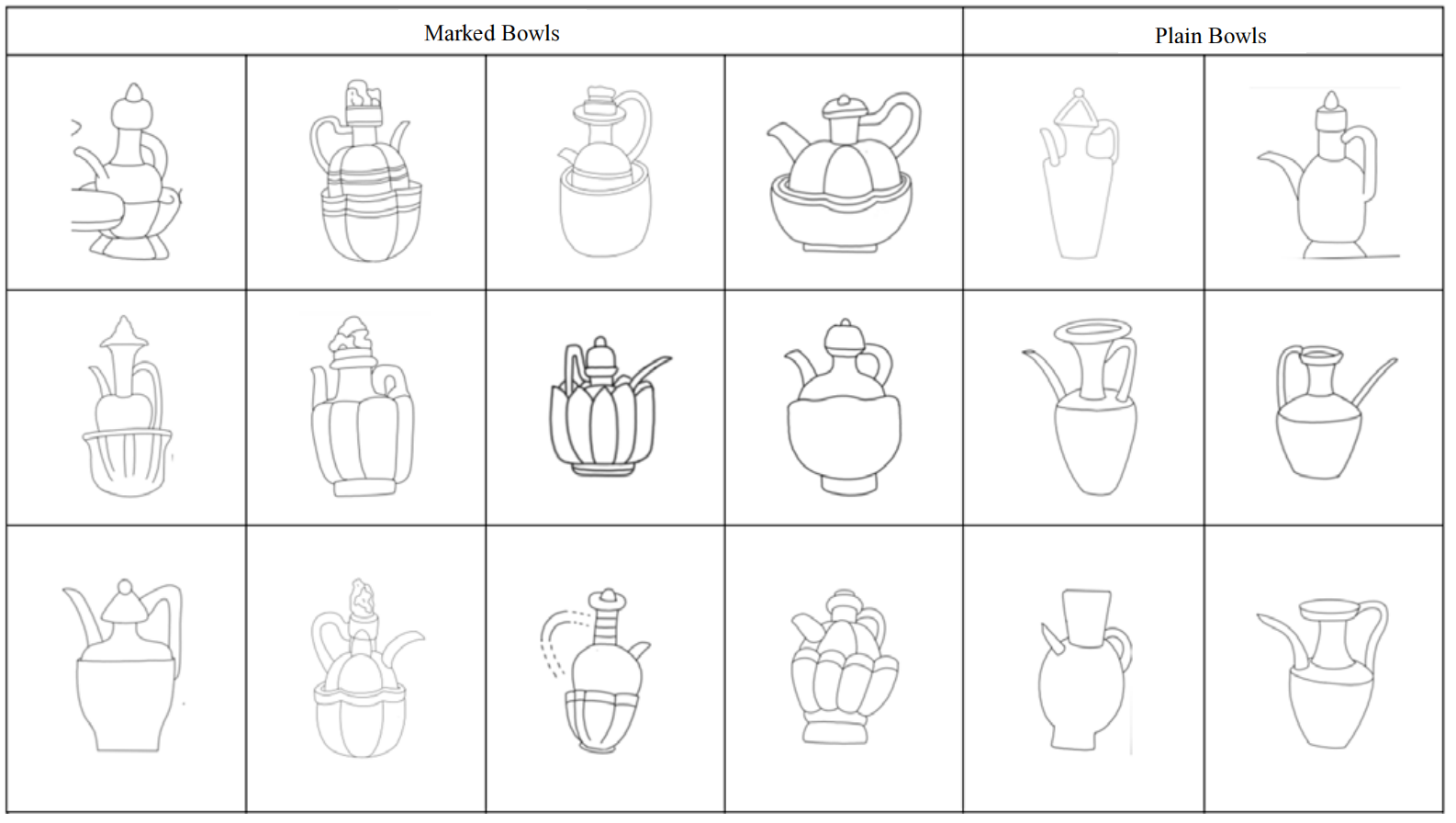

2.2.2. Wine Ewers and Bowls

Wine ewers and bowls frequently appear together in Northern Song tomb mural banquet scenes, particularly in depictions of seated couples. In these scenes, wine ewers are almost a standard component among dining utensils and are typically paired with bowls. A wine ewer is a type of vessel with a spout and handle. The use of wine ewers with bowls was influenced to some extent by the tea and wine culture of the Song Dynasty.

Before the emergence of distilled liquor in the Yuan Dynasty, Song Dynasty people believed that warming wine enhanced its aroma and softened its taste. Hot water was poured into a bowl, into which the wine ewer was placed to heat and maintain the temperature of the wine. This pairing allowed the wine to remain warm throughout the banquet, ensuring guests’ enjoyment. For tea drinking, the Song Dynasty’s popular “point tea” method required pouring hot water into teacups. The slender spout and handle of the wine ewer facilitated gripping and pouring during this process. As the water temperature for point tea needed to be high, water was typically boiled in another vessel and poured into the ewer, or the ewer was directly heated over a charcoal brazier.

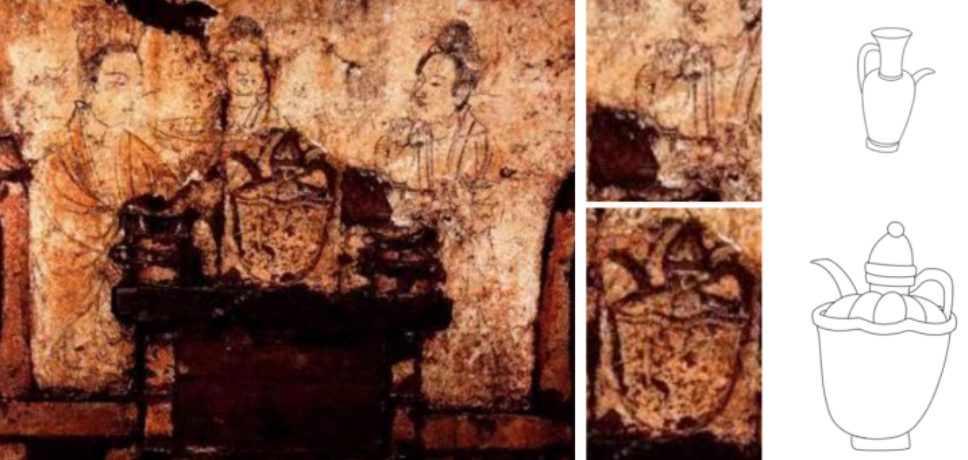

In the surveyed tomb murals, wine ewers paired with bowls appear significantly more frequently than standalone ewers. In some cases, both forms are depicted together. For example, in the couple’s banquet scene on the western wall of a Song Dynasty mural tomb in Chengnanzhuang, Dengfeng, Henan [8], a melon-shaped wine ewer with a bulging body, short neck, and lid is placed on the central table, encased in a fluted-rim bowl with a wide, straight-walled, deep body. Behind the table, a female attendant holds another wine ewer with a long neck, wide mouth, and a long handle extending from the rim to the shoulder. In this mural (Figure 5), the wine ewer paired with a bowl is noticeably larger than the standalone ewer.

Northern Song trays typically feature a wide, flat surface and a larger size, predominantly made of porcelain, reflecting the high level of ceramic craftsmanship and design during the Song Dynasty. Common shapes include circular, square, and petal-like forms, with circular trays being the most prevalent. The edges of trays are slightly upturned, facilitating handling and preventing items from slipping. Large trays can hold multiple cups or dishes simultaneously, making them suitable for multi-person banquets. This not only enhances the efficiency of banqueting but also adds a sense of ceremony.

2.1.3. Food Boxes

Food boxes frequently appear in banquet scenes depicted in Northern Song tomb murals as containers for holding items. During the Northern Song period, food boxes came in various shapes, including circular, square, and rectangular, to accommodate different types of food and occasions. In tomb murals, food boxes are predominantly depicted as cylindrical, with a minority being square. Their designs are elegant yet simple, typically featuring a multi-layered structure that facilitates the separation and storage of different foods. Song Dynasty banquets emphasized the pairing of wine and dishes, with a wide variety of culinary offerings. Food boxes were used to categorize and hold different foods, making them easy to access while maintaining the temperature and hygiene of the contents. The excellent containment properties of food boxes also made them suitable for transporting food during outdoor banqueting activities or for delivering cooked meals from taverns and restaurants. Food boxes were made from materials such as wood, bamboo, and porcelain, with hardwood being the most common due to its durability and resistance to damage despite its weight.

2.1.4. Bowls, Spoons, Chopsticks, and Other Utensils

Smaller eating utensils, such as spoons and chopsticks, are rarely depicted in banquet scenes in Northern Song tomb murals. The author suggests several possible reasons for this: the limited detail achievable in mural painting may have restricted the depiction of such small items; preservation conditions may have rendered them difficult to identify; or the stylized nature of banquet themes during this period may have led to their omission. Based on the tomb mural images and related literature reviewed in this study, the only documented instance of such utensils is found in the excavation report of Tomb No. 1 at Shizhuang, Jingxing County, Hebei. In the description of the couple’s banquet scene on the southeast wall (Figure 2), it is noted that “a horizontal brick on the table is carved with a bowl, plate, spoon, and wine ewer [3].”

2. Common Types of Dining Utensils in Northern Song Tomb Murals

In terms of accompanying dining utensils, items on the table are typically arranged symmetrically, symbolizing the formality and ritualistic nature of banqueting. Based on the primary types of food and drink they hold and their intended use, the utensils depicted in Northern Song tomb murals are categorized into two main groups: eating utensils and drinking utensils.

2.1. Eating Utensils

Eating utensils are used for consuming food during banquets and primarily include plates, dishes, bowls, spoons, and chopsticks.

2.1.1. Plates

Among the eating utensils depicted in Northern Song tomb murals, plates appear most frequently, second only to the drinking utensil category of saucer-cups in terms of occurrence. However, when counted by quantity, plates often appear in groups, making their total number exceed that of saucer-cups. Although their sizes vary, plates typically feature an open mouth, a shallow body, and a low ring foot or a flat base, with a few fluted rims, reflecting a simple and practical design. An abundance of delicacies characterized Song Dynasty banquets: “All manner of rare and delicious foods, seasonal side dishes, and exquisite vegetables were provided without omission [1].” Main courses, beverages, pastries, and fruits were paired together, with plates playing a key role in banquet preparation and banquet scenes, used to hold fruits, vegetables, and side dishes.

2.1.2. Trays

Trays are used to carry smaller plates, dishes, and drinking utensils. In banquet scenes, trays typically appear in the hands of attendants, either held or presented, their dynamic interaction with figures highlighting their function in transporting food and drink. Trays are sometimes paired with food covers, as seen in the banquet preparation scene on the northeast wall of the Song Silang brick-carved mural tomb in Shisi Li Village, Xin’an County, Henan [2]. In this example (Figure 1), a female attendant on the left holds a wide-mouthed white tray with both hands, on which a dark-colored food cover is placed.

In other banquet scenes, similar characteristics are observed (Figure 6): when wine ewers are paired with bowls in tomb murals, they typically feature a larger body, a relatively thicker spout, and a lid. In contrast, when not paired with bowls, wine ewers usually have a more slender spout, a smaller body with moderate capacity, a lightweight handle, and are mostly open-mouthed, with only a few having lids. These design features generally align with the functional analysis provided earlier. However, to accurately determine whether these ewers were used for tea or wine, it is best to consider the context of the accompanying utensils and the actions of the figures in the scene.

4. Analysis of the Forms of Daily Dining Utensils Depicted in Northern Song Tomb Murals

The Northern Song Dynasty, a pinnacle of material culture in ancient China, exhibited distinctive characteristics in the craftsmanship, aesthetic forms, and social functions of its dining utensils. Against the backdrop of a flourishing commodity economy, the rise of urban culture, and the growth of the scholar-official class, banqueting activities transcended mere dietary needs, evolving into a cultural arena that embodied ritual norms, aesthetic aspirations, and social identity. The dining utensils of this period not only met the practical demands of banqueting but also reflected the unique aesthetic style and advanced craftsmanship of the Northern Song.

4.1. Practical Forms

The material system of Northern Song dining utensils reflects a diverse and symbiotic pattern, encompassing ceramics, metals, lacquerware, and bamboo or wood. Considering the differences across social strata, nobles and scholar-officials likely used more expensive materials, such as gold, silver, or renowned kiln ceramics, while commoners primarily used ceramics or bamboo and wood utensils. Observations of Northern Song banquet scenes, combined with documentary evidence, indicate that the dining utensils depicted in tomb murals are predominantly ceramic. Although the level of detail in mural painting and preservation conditions often makes it difficult to identify specific kiln origins, the forms are generally simple and robust. These forms closely resemble the burial goods found in tombs, which are typically coarse ceramics from local kilns. This choice of utensils reflects both the economic constraints of wealthy commoner households and their consumption philosophy of prioritizing practicality over aesthetics.

Archaeological evidence from excavated artifacts further supports this analysis. Although Song Dynasty tomb burial goods reflect a trend toward frugality in both quantity and value, some items align closely with the utensil compositions described in banquet scenes. For example, the Northern Song tomb in Jianbi, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu (Figure 13), yielded nine pieces of yingqing (shadow-blue) porcelain, including one set of a wine ewer with a warming bowl, two sets of wine cups with saucers, one high-footed cup, one yingqing bowl, and one three-section melon-shaped box [10]. This collection represents some of the earliest known Northern Song yingqing porcelain, providing valuable material evidence for the study of wine utensils, particularly the pairing of ewers with warming bowls and cups with saucers. Similarly, the mid-to-late Northern Song dated tomb of Wu Zhengchen and his wife in Susong County, Anhui, yielded ninety-six ceramic pieces (or sets), including twenty-one bowls (or cups), thirty-three dishes (or plates), two basins, two large bowls, six sets of saucers, thirteen jars, eight double-handled bottles, three meiping (plum vases), five handled pots, two sets of wine ewers with warming bowls, and one incense burner set (Figure 14). The large quantity and high quality of these ceramics provide significant reference material for studying Northern Song ceramic forms and decorations. [11].

Abstract

Banqueting was a cornerstone of Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE) social life, with dining utensils serving as vital artifacts that embodied the era’s aesthetic sensibilities, social customs, and cultural values. This study examines the typology, forms, and compositional arrangements of utensils depicted in Northern Song tomb murals, drawing on archaeological evidence from sites in Henan and Hebei, textual records, and surviving ceramics. It elucidates the ritual frameworks, social hierarchies, and dining practices reflected in banquet scenes, offering a comprehensive analysis of their role in Northern Song society. By correlating mural depictions with material artifacts, this research provides fresh insights into the interplay of functionality and symbolism in banquet culture and establishes a methodological framework for evaluating the authenticity and interpretive potential of historical imagery. The study underscores the critical role of material culture in reconstructing past social practices, contributing to a deeper understanding of Northern Song cultural history.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Yuanjun Cui, and Hong He, "Forms and Functions of Dining Utensils in Northern Song Tomb Murals: Archaeological Insights." JACAC 3, no.2 (2025): 1-25.

AMA Style

Cui YJ, Hong H. Forms and Functions of Dining Utensils in Northern Song Tomb Murals: Archaeological Insights. JACAC. 2025; 3(2): 1-25.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References and Notes

1. [Song Dynasty] Wu, Zimu. Mengliang Lu, vol. 8, The Imperial Palace. Beijing: China Commercial Press, 1982, 57.

[宋]吴自牧.梦梁录[M]:卷八•大内.北京:中国商业出版社.1982.57.

2. Yu, Lina, Zhang, Jianwei, Yu, Haoran, et al. “A Brief Report on the Survey and Mapping of the Northern Song Dynasty Song Silang Brick Carving and Mural Tomb in Lijia Village, Shishi, Xin’an County.” Palace Museum Journal, no. 1 (2016): 71–87, 161.

俞莉娜,张剑葳,于浩然,等.新安县石寺李村北宋宋四郎砖雕壁画墓测绘简报[J].故宫博物院院刊,2016,(01):71-87+161.

3. Tang, Yunming. “Excavation Report on the Song Dynasty Tomb at Shizhuang, Jingxing County, Hebei.” Acta Archaeologica Sinica, no. 2 (1962): 31–73, 124–153.

唐云明.河北井陉县柿庄宋墓发掘报告[J].考古学报,1962,(02):31-73+124-153.

4. [Song Dynasty] Shen’an Laoren, et al. Illustrated Commentary on Tea Utensils and Three Other Works. Hangzhou: Zhejiang People’s Fine Arts Publishing House, 2013.

[宋]审安老人等,茶具图赞外三种[M],杭州:浙江人民美术出版社,2013.

5. Su, Bai. Baisha Song Tombs. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 2017.

宿白.白沙宋墓[M].北京:生活•读书•新知三联书店,2017.

6. Chen, Jing. “Lacquerware Unearthed from the Song Dynasty Tomb in Beihuan New Village, Changzhou.” Archaeology, no. 8 (1984): 730–732, 736.

陈晶.常州北环新村宋墓出土的漆器[J].考古,1984,(08):730-732+736.

7. Yan, Yong, Zhang, Yingjun, Yang, Wenyu, et al. “A Brief Report on the Excavation of the Song Dynasty Mural Tomb in Nanwuli Village, Laizhou, Shandong.” Cultural Relics, no. 2 (2016): 4–20.

闫勇,张英军,杨文玉,等.山东莱州南五里村宋代壁画墓发掘简报[J].文物,2016,(02):4-20.

8. Han, Rong, Wang, Linxiu. “A Study of Culinary Utensils in the ‘Banquet Scenes’ of Song and Jin Dynasty Tombs.” Creativity and Design, no. 4 (2020): 41–46.

韩荣,王琳琇.宋金墓葬“宴饮图”中饮食器具考略[J].创意与设计,2020,(04):41-46.

9. Si, Yuqing, Huo, Baocheng, Duan, Qi, et al. “Appreciation of the Northern Song Dynasty Dated Mural Tomb in Guxian, Hebi.” Cultural Relics Identification and Appreciation, no. 8 (2015): 88–91.

司玉庆,霍保成,段琪,等.鹤壁故县北宋纪年壁画墓鉴赏[J].文物鉴定与鉴赏,2015,(08):88-91.

10. Xiao, Menglong. “Porcelain Unearthed from the Northern Song Dynasty Tomb in Jianbi, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu.” Archaeology, no. 3 (1980): 246–247.

肖梦龙.江苏镇江谏壁北宋墓出土的瓷器[J].考古,1980,(03):246-247.

11. Liu, Dong. “Analysis of Porcelain Unearthed from the Northern Song Dynasty Tomb of Wu Zhengchen and His Wife in Susong County, Anhui.” Journal of Hunan Provincial Museum, no. 0 (2021): 431–438, 21–23.

刘东.安徽宿松县北宋吴正臣夫妇墓出土瓷器探析[J].湖南省博物馆馆刊,2021,(00):431-438+21-23.

12. Zong, Huabai. A Stroll Through Aesthetics. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 1981, 37.

宗华白.美学散步.[M].上海:上海人民出版社,1981:P37.

13. Xue, Qiao, Liu, Jinfeng, Chen, Chunhui. “A Study of Song and Yuan Dynasty Black-Glazed Tea Utensils.” Agricultural Archaeology, no. 1 (1984): 164–176.

薛翘,刘劲峰,陈春惠.宋元黑釉茶具考[J].农业考古,1984(01):164-176.

14. [Song Dynasty] Zhao, Ji, et al. Treatise on Tea. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press, 2018.

[宋] 赵佶等著.大观茶论[M].九州出版社.2018.

15. Tian, Zibing. History of Chinese Arts and Crafts. Shanghai: Shanghai Orient Publishing Center, 1985, 238.

田自秉.中国工艺美术史[M].上海东方出版中心出版,1985:238.

16. Li, Zhiyan. The History and Authentication of Ceramic Development. Beijing: Hualing Publishing House, 2004, 252.

李知宴.陶瓷发展的历史和辨伪[M].华龄出版社2004:252.

17. Zhang, Jianhua, Hao, Hongxing, Li, Weidong, et al. “The Song Dynasty Mural Tomb in Pingmo, Xinmi City, Henan.” Cultural Relics, no. 12 (1998): 26–32, 100.

张建华,郝红星,李卫东,等.河南新密市平陌宋代壁画墓[J].文物,1998,(12):26-32+100.

18. Yu, Hongwei, Huang, Jun, Li, Yang. “A Brief Report on the Excavation of the Mural Tomb in Gaocun, Dengfeng.” Cultural Relics of Central China, no. 5 (2004): 4–12.

于宏伟,黄俊,李扬.登封高村壁画墓清理简报[J].中原文物,2004,(05):4-12.

19. Zhang, Duisheng, Zhang, Zengwu, Miao, Dongsheng, et al. “A Brief Report on the Excavation of the Song Dynasty Mural Tomb in Lijiachi, Linzhou City, Henan.” Huaxia Archaeology, no. 4 (2010): 32–39, 121, 153–164.

张堆生,张增午,苗东生,等.河南林州市李家池宋代壁画墓清理简报[J].华夏考古,2010,(04):32-39+121+153-164.

20. Li, Yang, Wang, Xu, Yu, Hongwei, et al. “The Song Dynasty Mural Tomb in Heishangou, Dengfeng, Henan.” Cultural Relics, no. 10 (2001): 60–66, 2.

李扬,汪旭,于宏伟,等.河南登封黑山沟宋代壁画墓[J].文物,2001,(10):60-66+2.

Author Contribution

Yuanyun Cui was responsible for literature review, data collection, and drafting the initial manuscript. Hong He contributed to defining the research approach, designing the paper’s framework, providing theoretical guidance, and revising the final manuscript.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Author Biographies

- Yuanyun Cui is a master’s student at the China Academy of Art, specializing in the study of statues and artifacts, as well as cultural heritage conservation and restoration.

- Hong He is an associate professor and master’s supervisor at the China Academy of Art, serving as the deputy director of the Craft and Arts Committee of the China Cultural and Art Development Promotion Association and as a member of the China Dunhuang and Turfan Society. He has led numerous national and provincial research projects and published extensively. He has also organized and curated over 30 exhibitions for the global tour “One Hundred Libraries, One Hundred Dunhuang Exhibitions” and delivered more than 200 Dunhuang-themed lectures both domestically and internationally.

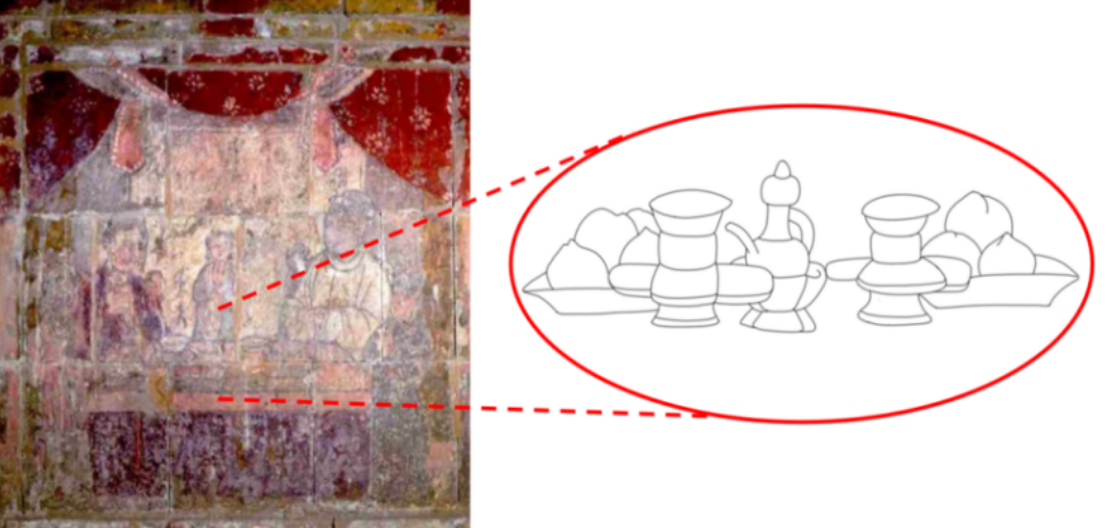

3.1.2. Expanded Utensil Category Configuration

The second category builds upon the first configuration (“one ewer, two cups”) by incorporating additional types of dining utensils around the table. Examples include the couple’s banquet scene on the northwest wall of the Song Dynasty mural tomb in Tangzhuang, Dengfeng, Henan (Figure 10); the couple’s banquet scene on the northern wall of the Song Silang brick-carved mural tomb in Shisi Li Village, Xin’an County, Henan (Figure 11); the banquet scene on the southern wall of the Song Dynasty brick-carved tomb in Wangjia Xinyao, Tianshui City, Gansu; and the banquet scene on the western wall of Song Tomb No. 2 in Shizhuang, Jingxing County, Hebei. In these murals, plates are added to the tabletop arrangement.

1.1. Background and Regional Distribution

The Northern Song Dynasty championed Neo-Confucian ideals, emphasizing a simple and frugal lifestyle to curb desires. Consequently, funerary practices and regulations were relatively pragmatic, with modest grave goods. However, the Song Dynasty placed great importance on “managing funerals” (治丧), investing heavily in activities such as wakes and burials, and meticulously designing tomb architecture. Tombs featured imitation wooden structures, including corbelled brackets, columns, doors, and windows, transforming burial chambers into spaces resembling residences or courtyards. Compared to previous dynasties, the Song government adopted a more relaxed stance on regulating private funerary practices. This leniency allowed the construction of mural-adorned tombs to meet the needs of local gentry and landowners to demonstrate filial piety and assert social status. The combination of tomb murals and brick chambers with imitation wooden structures formed the core of tomb decoration, leading to the gradual development and increasing richness and refinement of Northern Song folk tomb murals.

Analysis and screening of the content depicted in Northern Song tomb murals reveal that approximately 70% of tombs with banquet scenes are located in Henan Province. The regional distribution shows a pattern radiating outward from Henan as the center, with mural styles in northern regions developing more advanced characteristics compared to those in the south. This highlights the radiating influence of Bianjing (modern-day Kaifeng), the political and cultural capital, on surrounding areas.

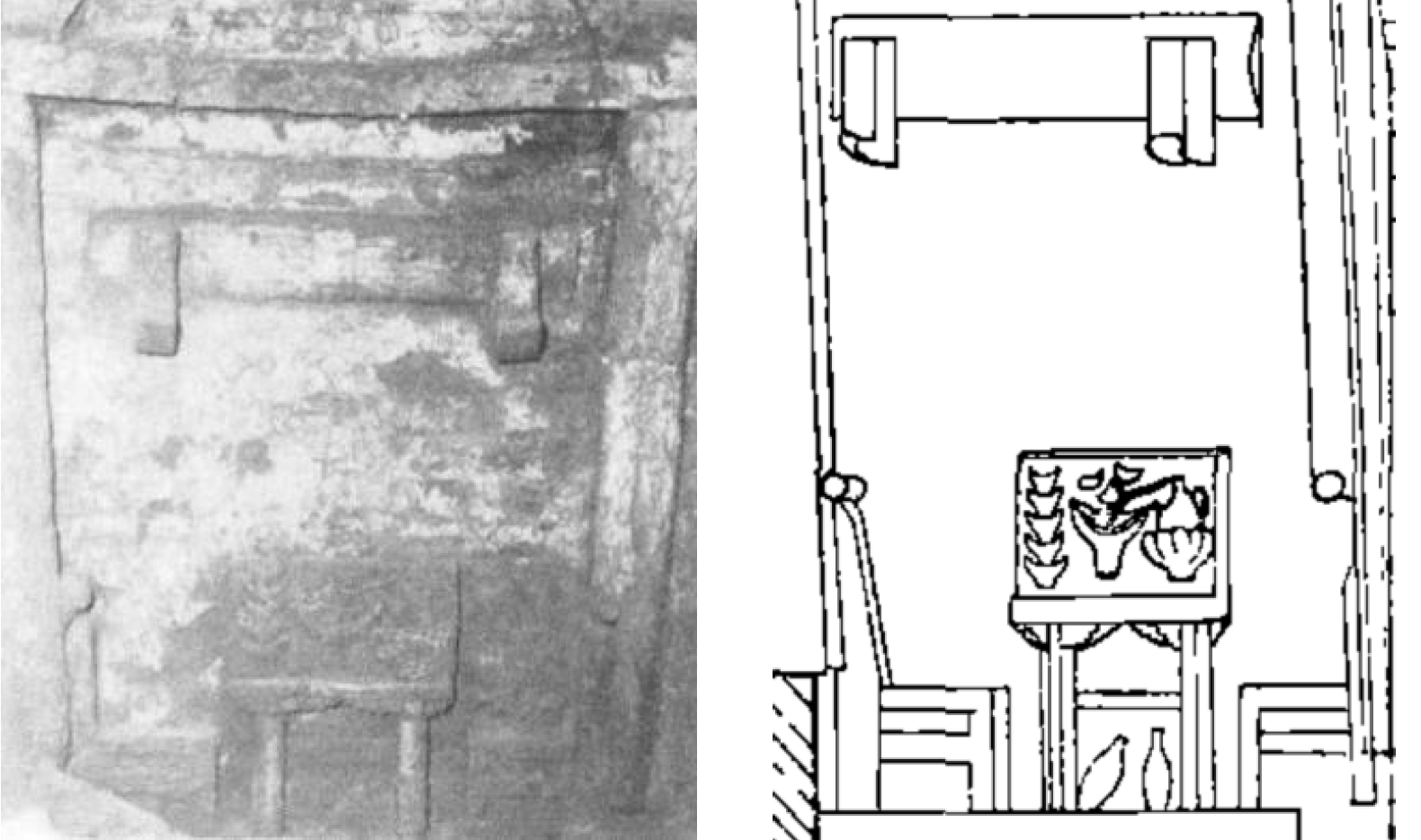

1.2. Layout Forms and Developmental Characteristics

Dining utensils serve the banqueting activities of individuals, and as the owners of the tombs, the tomb occupants are often depicted alongside these utensils in tomb murals. By analyzing records such as land deeds and epitaphs, it is evident that the occupants of Northern Song tombs featuring banquet scenes were predominantly wealthy landowners or gentry. The presence of banquet scenes in tombs likely reflects the affluent class’s desire to showcase their prosperous lifestyle and create an impression of vitality. The tomb structures and decorations mirror real-life settings, with banquet scenes typically located on the eastern and western walls. In the early Northern Song period, these murals primarily depicted utensils. By the mid-period, banquet murals increasingly included images of the tomb occupants. By the late period, a standardized form of “couple banquet scenes” had emerged. Analysis of these compositions reveals distinct patterns in the layout of the tomb occupants’ images and the arrangement of utensils. The tomb occupants, typically a couple, are depicted in configurations such as “sitting together at one table,” “sitting at separate tables facing each other,” or “sitting at one table with two chairs facing each other,” with the latter being the most common. The dining utensils in these tomb murals correspondingly emphasize symmetry and ritualistic qualities.

In addition to the seated couple configuration, Northern Song tomb murals also depict banquet scenes through formats such as banquet preparation and tea-serving scenes. These images typically do not include the direct participation of the tomb occupants but vividly portray the activities of attendants preparing for the banquet. The depicted space often shifts from the “dining room,” where banqueting occurs, to the “kitchen,” where preparations take place. For instance, kitchen scenes primarily illustrate daily cooking activities, such as preparing food and arranging utensils. Wine preparation scenes are often combined with kitchen scenes, showcasing the process of warming wine. Tea preparation scenes depict the steps involved in making tea, including boiling water, brewing tea, performing the “point tea” method, and serving tea.

3.2. Cultural Characteristics of Compositional Forms

The arrangement of dining utensils in tomb murals exhibits distinct patterns, with utensils often appearing in sets and neatly arranged, reflecting the importance placed on dining etiquette during the period. In the early Northern Song, the Kaibao Tongli established national ceremonial protocols, which were further refined by Ouyang Xiu’s Taichang Yinge Li and later Song Dynasty ritual texts, edited with contributions from Ouyang Xiu and Su Xun, detailing banquet procedures such as seating arrangements, utensil specifications, and procedural protocols for various occasions. These regulations, formalized and promulgated by the state, underscore the ruling class’s emphasis on banqueting activities, with official practices significantly influencing private dining customs.

The placement of utensils in banquet scenes provides insight into the Song Dynasty’s dining system. In the historical evolution of China’s dining practices—shifting from individual, communal, to shared dining—the Song Dynasty solidified the shared dining system, a practice still prevalent today. The high tables and chairs commonly depicted in Song Dynasty banquet scenes emerged under the influence of Central Asian styles in the late Tang Dynasty. Before this, low furniture, such as tables and stools close to the ground, was used, with diners seated separately, each with their own table and primarily consuming individual portions. During the Song Dynasty, high-backed chairs and tall tables became widespread, fostering a new trend of multiple people dining together at a single table. This shared dining system gradually replaced individual dining, promoting closer interpersonal relationships. Consequently, couple’s banquet scenes carry the symbolic meaning of marital harmony and familial happiness.

Regarding utensil types, saucer-cups, wine ewers, and plates frequently appear, indicating their essential role in Song Dynasty banquets. This reflects the widespread popularity of tea and wine drinking, often paired with eating activities. In some cases, tea and wine drinking occur within the same banquet, suggesting a structured sequence in Song dining practices. The prevalence of plates highlights the richness of Song cuisine and the etiquette of shared dining, with the number of utensils often corresponding to the number of participants, indicating standardized sets of dining utensils in shared dining contexts. The presence of food boxes and slender-necked bottles (jingping) reflects the portability of Song Dynasty cuisine, likely used for transporting food and drink in shops or for outdoor banquets. The depiction of dining utensils in tomb murals, through their imitation of secular household furnishings, recreates a familiar banqueting atmosphere for the tomb occupants in the afterlife, offering a vivid snapshot of the domestic life and environment of that era.

These artifacts, all used in daily life, closely match the forms and quantities described in banquet scene analyses: bowls and dishes are the most numerous, featuring both round and fluted rims; saucers come in two styles—one with a high ring foot and a flat-topped disc shape, with a hollow interior connected to the foot, and another flatter style with a fluted rim. Wine ewers are paired with warming bowls, and white-glazed meiping likely served as accompanying wine vessels. The ceramics originate from multiple kilns, reflecting the robust commodity exchange of the Northern Song and the refined aesthetic sensibilities of the period. The emergence of standardized sets of dining utensils highlights that Song people valued both the practical utility and aesthetic appeal of their utensils.

4.2. Aesthetic Style

The dining utensils depicted in Northern Song tomb murals exhibit an overall style that is elegant, dignified, simple, and refined. This style is closely tied to the social and cultural context of the period. Influenced by traditional Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist philosophies, Song Dynasty aesthetics favored “plainness,” advocating for the inherent beauty of objects in their natural state and embracing a return to simplicity while rejecting excessive ornamentation and vulgarity. This philosophical inclination is reflected in the utensils’ minimalist and refined aesthetic. The reverence for nature is evident in the biomorphic designs of some dining utensils, such as the iconic lotus-shaped warming bowls of the Song Dynasty. These bowls, with rims shaped to evoke the lotus flower—symbolizing purity emerging unsullied from the mud—embody a design inspired by nature, serving as a material expression of Song craftsmanship and aesthetic consciousness.

As Mr. Tian Zibing notes in History of Chinese Arts and Crafts, the appreciation of Song ceramics stems from the meticulous attention to every detail of the vessel’s form and the precise control of proportions. The concept of “heaven round, earth square”(天圆地方) is a traditional Chinese design principle that influenced the prevalence of circular and square forms in dining utensils [12]. While Song Dynasty designs appear simple and understated, their lines convey an intrinsic, subtle beauty. By eliminating superfluous elements, these designs primarily employ simple geometric shapes, inheriting traditional aesthetic principles while expressing the Song people’s ideals of balance, variation, and unity in a refined manner.

4.3. Rustic Charm

Song Dynasty aesthetic philosophy leaned toward subtlety and simplicity, significantly influencing the color palette of dining utensils, which predominantly favored understated elegance. Based on observations from banquet scenes, ceramic utensils are the most prevalent in Northern Song tomb murals, with bamboo, wood, and metal utensils often retaining the “natural” or “authentic” color of their materials. Therefore, the following analysis of utensil colors focuses primarily on ceramic dining utensils. During the Northern Song, aesthetic sensibilities advanced dramatically, driving unprecedented developments in ceramic production, with renowned kilns flourishing. In Chinese tradition, jade has long been regarded as a symbol of beauty, making celadon and white porcelain—colors akin to jade—widely cherished. Although mural colors can only convey general hues, light and gray-toned utensils appear across banquet scenes of various social strata, corroborated by numerous excavated artifacts of similar forms and colors. The subdued tones of celadon and white porcelain convey a gentle, elegant, and serene color language, aligning with the Song people’s pursuit of tranquil simplicity.

In addition to celadon and white porcelain, dark-colored utensils are also documented in Northern Song banquet scenes. The Song and Yuan periods marked the peak of black-glazed porcelain production [13]. Emperor Huizong, in his Treatise on Tea, praised “Blue-black glaze is considered the finest quality” (色贵青黑) glazes as superior [14], reflecting the esteemed status of dark-colored utensils in Song aesthetics. Whether celadon, white, or black-glazed, these colors exude a refined and transcendent beauty, resonating with both the aesthetic preferences and cultural ambiance of the period.

The dining utensils in banquet scenes consistently exhibit a simple and elegant appearance, with most vessels featuring plain, unadorned surfaces. The few utensils decorated with patterns or incised designs remain restrained, avoiding excessive opulence. In Northern Song banquet scenes, utensil decorations are rarely prominent, reflecting the period’s preference for subtle and refined ornamentation. As Mr. Tian Zibing notes in History of Chinese Arts and Crafts, “Song Dynasty arts and crafts possess an elegant and approachable style. Whether ceramics, lacquerware, metalwork, or furniture, they excel through unpretentious forms with minimal ornate decoration, evoking a sense of understated beauty [15].” Regarding craftsmanship, Li Zhiyan, in History and Authentication of Ceramic Development, describes Song porcelain decoration as diverse, employing techniques such as “incising, printing, carving, and stippling,” which are widely used and characterized by “lively content, clear layering, and orderly arrangement [16].” Techniques like printing and incising are applied to the ceramic body before glazing, often appearing subtle from a distance and requiring close inspection to appreciate their nuanced charm.

(a) Six-Petaled Flower-Rimmed Dish

(c) Zhu with Warming Bowls

In the foreground, a decorated stove holds a vessel, with a nearby attendant crouching and leaning forward, facing the stove, as if checking whether the water has boiled, tasked with monitoring the heating process. Behind the table, three attendants stand: the one on the left holds a shallow dish with an open-mouthed cup, appearing to deliver it to the host, who is responsible for serving food. The attendant on the right holds a knife in one hand and presses an item with the other, engaged in cutting ingredients, responsible for food preparation. Each attendant performs a specific role, collectively forming a critical part of the banquet preparation process. This detailed division of kitchen labor appeared in the Northern Song among royal and noble households as well as affluent commoner families, laying the groundwork for the establishment of the “Four Departments and Six Bureaus”(四司六局) in the Southern Song period. Characterized by meticulous task allocation, streamlined processes, and professional service, this system had a profound influence on later banqueting practices.

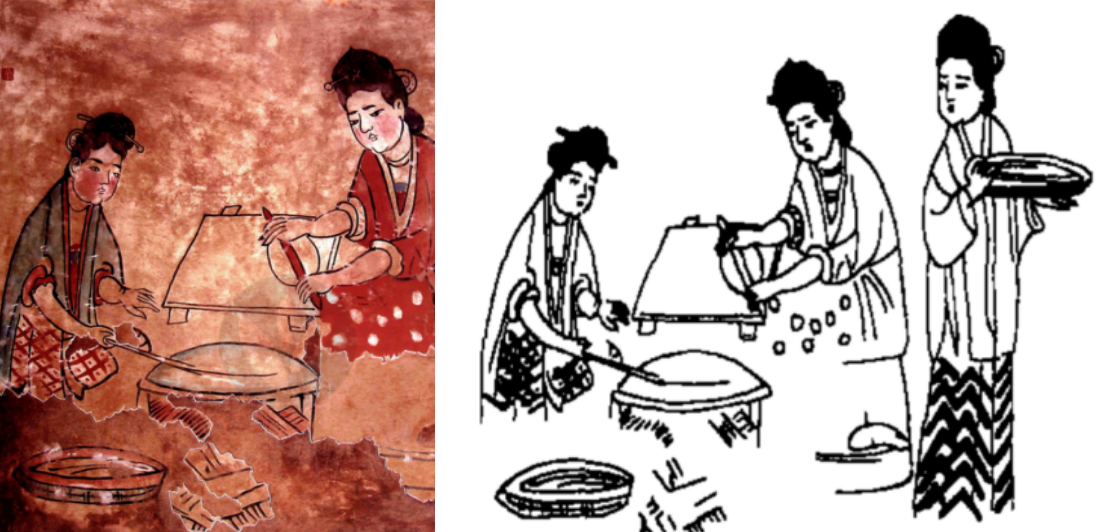

5.4. Diverse Culinary Varieties

The utensils and the foods they contain or are used to prepare in banquet scenes reflect the advancements in Song Dynasty culinary techniques. Through methods such as steaming, boiling, roasting, and stir-frying, refined dishes were crafted to suit diverse tastes. For example, the pancake-making scene on the western wall of the Song Dynasty mural tomb in Gaocun, Dengfeng, Henan [18], depicts three women: one holding a tray, while the other two stand facing each other, engaged in pancake preparation (Figure 16). The woman wearing a blue jacket and a diamond-patterned apron has her sleeves rolled up, using an iron rod in her right hand to flip pancakes on a flat iron griddle, commonly known as an aozi or griddle pan, with a fire burning vigorously beneath it. To the right is a round box containing finished pancakes. The woman in a red jacket and red floral apron, also with sleeves rolled up, uses both hands to wield a rolling pin on a low table to roll out dough for pancakes. Similarly, the kitchen scene on the northern wall of the Song Dynasty mural tomb in Lijiachi, Linzhou City, Henan [19], features a male cook kneading dough, alongside a yellow steamer on a stove by the table. These depictions illustrate that Song people employed a variety of cooking methods to prepare food.

5.4.1. Tea tasting

During the Northern Song Dynasty, tea and wine were the predominant beverages. An examination of various banquet images reveals that scenes of banquet preparation, such as tea brewing, wine serving, and kitchen activities, frequently accompany depictions of banqueting. This illustrates the flourishing tea and wine culture of the Song Dynasty, where tea drinking and wine consumption became integral to daily life, often occurring alongside meals. The history of tea in China can be traced back to the mythical Shen-nong era, when tea was primarily used for its medicinal properties. During the Jin and Northern Dynasties, tea began to assume a cultural significance. By the Tang Dynasty, tea had become a staple of daily life. The Song Dynasty played a pivotal role in the development of Chinese tea culture, serving as a bridge between earlier and later traditions. During this period, tea became accessible to the common people, and tea culture permeated social customs, intellectual thought, and religious beliefs, exerting a profound influence on later Chinese traditions as well as the tea ceremonies of Japan and Korea.

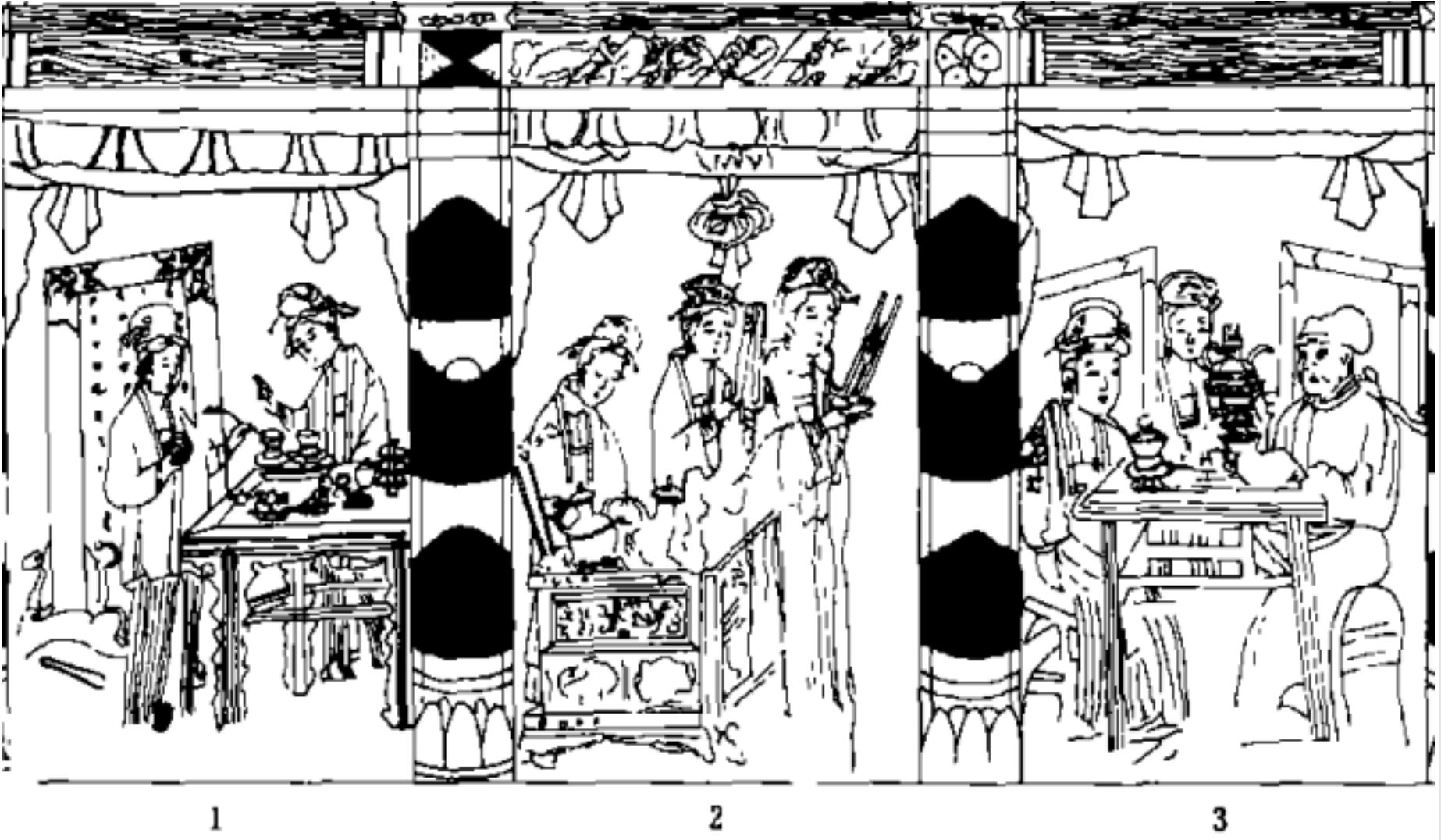

The culinary utensils depicted in Song Dynasty tomb murals also document the distinctive “point tea method” (点茶法) of the era. According to texts such as Cai Xiang’s Record of Tea (茶录) and Emperor Huizong’s Treatise on Tea (大观茶论), the point tea method involved a series of meticulous steps: preparing utensils, washing tea, roasting tea, grinding tea, sifting tea, selecting water, choosing fire, boiling water, preparing tea-cups, and point tea (which includes blending the paste and whisking). For instance, the tea preparation scene depicted on the southwest wall of the Song Dynasty tomb at Heishangou, Dengfeng, Henan, vividly captures the process of point tea, tea serving, and tea drinking in the Song Dynasty (Figure 17) [20]. In the lower left corner of the west wall, a rectangular brazier is illustrated, with two copper chopsticks inserted at one corner. Inside the brazier, burning charcoal heats two long spouted, handled kettles used to boil water for tea preparation. A maidservant stands nearby, bending forward and attentively monitoring the brazier, waiting for the water in the kettles to reach boiling before pouring it into teacups for brewing. On the southwest wall, two maidservants are shown performing the point tea process. To the right, a square table holds a stack of teacups, a small jar, and a fruit tray. One maidservant behind the table holds a tray with two paired teacups and saucers, while another maidservant at the table’s side holds a teaspoon, stirring the tea in a cup to complete the point tea steps. The northwest wall features a banqueting scene, with three images illustrating the sequence of boiling water, preparing tea, and serving tea during a banquet.

5.4.2. Wine Drinking

In Song Dynasty society, while tea drinking flourished, the culture of wine consumption thrived unabated. The frequent appearance of wine-related utensils—such as saucer-cups, warming bowls, and slender-necked bottles—in various banquet scenes underscores wine’s pivotal role in Northern Song social and cultural life, significantly influencing the evolution of utensil designs. The Song period saw a marked increase in the height of tables and chairs, elevating diners above the level of food and drink. This shift emphasized the importance of the wine ewer’s practicality: its body became more elongated, the handle-to-body space widened, and its size decreased, facilitating easier handling and pouring. These adaptations simplified complex procedures, fostering a more relaxed and informal wine-drinking experience. The popular Song practice of warming wine profoundly shaped the ewer’s function and form. The heated wine is poured into a zhu (wine warmer) and then into a zhan (cup). This places high demands on the insulation function of the zhu. As a result, Song Dynasty zhu not only featured higher circular feet, a slender overall shape, and a smaller mouth, but also incorporated a lid and a zhuwan (warming bowl). While design evolved aesthetically, it also became more practical. The zhuwan has a wide, straight-walled, and deep design, allowing the zhu to be placed inside it with hot water poured in to warm the wine. This gave rise to the iconic image of the zhu and zhuwan, often depicted in tomb murals.

The combination of zhu and zhuwan, surrounded by long-necked bottles for storing wine and other utensils such as cups, plates, and zun (wine vessels), formed a wine-centered usage scene in banquet illustrations. This provides ample evidence for later generations to understand the functions of these vessels. The close correspondence between dining utensils, banquet procedures, and serving personnel highlights the refinement and sophistication of Song Dynasty dining culture.

Conclusion

The Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127 CE) built upon earlier traditions to develop a distinctive banqueting culture marked by secularization, refinement, and ritualization. Dining utensils in Northern Song tomb murals, particularly from sites in Henan and Hebei, serve as both functional tools and cultural symbols, reflecting the era’s aesthetic and social values. The standardized “one table, two chairs” composition and minimalist utensil arrangements in these banquet scenes do not indicate simplicity but rather craft a deliberate, solemn ritual atmosphere through simplified utensil types and symmetrical layouts. Saucer-cups and wine ewers, frequently depicted, highlight the centrality of tea and wine in Song dining culture, often complementing culinary activities, while sets of plates underscore the sophistication of Song cuisine.

Characterized by simple, geometric forms, these utensils balance practicality with aesthetic elegance, featuring natural material hues or refined tones like celadon, white, or black, with minimal ornamentation. The shift from individual to shared dining systems is evident in standardized utensil sets, which embody both functionality and ritual symbolism, offering key insights into transformations in Song social practices. These artifacts reveal the Song people’s refined tastes and aesthetic preferences, meeting practical needs while encapsulating profound cultural and artistic aspirations, reflective of a restrained yet sophisticated lifestyle.

Banquet scenes provide a rich contextual framework for understanding utensil functions, with depicted figures’ actions and object arrangements offering precise evidence of their use. Compared to textual records, these murals offer a more vivid and intuitive portrayal of dining practices; in contrast to physical artifacts, they provide a stronger contextual narrative, presenting a microcosm of Northern Song social life. By analyzing the forms, origins, and stylistic characteristics of these utensils, this study elucidates their symbolic meanings and cultural significance, contributing to a deeper understanding of Northern Song banqueting culture. Integrating visual, material, and textual evidence, this research underscores the pivotal role of tomb murals in reconstructing the cultural landscape of the era, providing essential visual and material evidence for studying Northern Song history and its enduring legacy.